Appendix 27: Final Report on Heritage Impacts By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KWAKIUTL BAND COUNCIL PO Box 1440 Port Hardy BC Phone (250) 949-6012 Fax (250) 949-6066

1 KWAKIUTL BAND COUNCIL PO Box 1440 Port Hardy BC Phone (250) 949-6012 Fax (250) 949-6066 February 5, 2007 Att: Mr. Rich Coleman, RE: GOVERNMENT APPROVAL FOR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS LAND TRANSFER AND INFRINGEMENT OF THE KWAKIUTL FIRST NATION DOUGLAS TREATIES AND TRADITIONAL TERRITORY We learned of the BC Government’s approval of Western Forest Product’s application to remove private lands from its Tree Farm License via news broadcasts. Our relationship, or lack of it, with Western Forest Products and the Ministry of Forests and Range is indicative of the refusal to openly discuss the application and especially when the Kwakiutl First Nation Council met with them on October 4th and 18th of 2006 (contrary to what we stated at these two meetings that this was not consultation nor accommodation). Western Forest Products historically has been blatantly allowed to disregard their obligations by your “watchdogs” to notify First Nation communities of their harvesting plans. These plans have, and always will have, the end result of infringement on our Treaty and Aboriginal rights and title as it exists for our traditional territory. This situation is further exacerbated by non-notification from your office of the recommendation to approve Western Forest Product’s application. It should be obvious to your ministry that there is the obligation to meaningfully consult and accommodate with First Nations and that message should have been strongly stressed to Western Forest Products. Western Forest Products has touted that it has good relationships with First Nations communities on its website but when we look at our relationship with them, the Kwakiutl First Nation must protest that Western Forest Products and Ministry of Forests and Range do not entirely follow legislated protocol. -

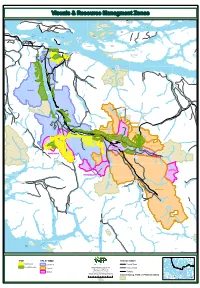

Visuals & Resource Managment Zones

Visuals & Resource Managment Zones Port Elizabeth Trinity G I L F O R D I S L A N D Bay BROUGHTON ARCHIPELAGO Single Tree CONSERVANCY Pt. SUQUASH Lady Islands BROUGHTON ARCHIPELAGO Knight Inlet Sointula MARINE " PARK Mitchell Village Bay Island BROUGHTON Swanson CORMORANT CHANNEL Island Ledge Pt. CORMORANT Cluxewe STRAIT CHANNEL Port McNeill Harbour MARINE Turnour Island PARK Port McNeill Alert Bay " " Clio Channel Harbledown Island Flagstaff Is. Hanson Island WHITE DUCK LAKE Telegraph Cove " LOWER NIMPKISH Beaver Cove QWIQUALLAAQ/BOAT West Cracroft Island PARK BAY CONSERVANCY Cub Lake J O H N S T O N E ROBSON BIGHT (MICHAEL Robson BIGG) ECOLOGICAL Bight RESERVE LOWER TSITIKA RIVER PARK TSITIKA MOUNT MOUNTAIN DERBY ECOLOGICAL ECOLOGICAL RESERVE RESERVE Nimpkish Nimpkish Lake Bonanza Lake Tsitika NIMPKISH Nimpkish LAKE " PARK CLAUDE ELLIOTT ECOLOGICAL RESERVE TSITIKA RIVER ECOLOGICAL MOUNT RESERVE ELLIOTT ECOLOGICAL RESERVE CROSS LAKE Woss-Vernon Highway 19 Woss-Vernon Tsitika Atluck Lake Woss " TAHSISH Woss-Vernon KWOIS PARK TSITIKA-WOSS SCHOEN LAKE PINDER-ATLUCK PARK Woss-Vernon Lower Schoen Klaklakama Lake TAHSISH Lake RIVER ECOLOGICAL RESERVE ARTLISH CAVES PARK Woss Lake SCHOEN- STRATHCONA Tahsish Inlet WOSS-ZEBELLOS . Moketas Island WOSS LAKE PARK NIMPKISH RIVER ECOLOGICAL Fair Harbour RESERVE " DIXIE COVE MARINE PARK Woss-Vernon Vernon Lake Zeballos " Zeballos Inlet Espinosa Inlet Tahsis " Port Eliza WEYMER CREEK PARK TAHSIS INLET Muchalat Lake GOLD MUCHALAT PARK CATALA ISLAND MARINE PARK Catala ESPERANZA INLET Island NUCHATLITZ PARK "" VQO TFL37 RMZ Transportation Sayward " Modification Enhanced Paved Road Partial Retention Tree Farm Licence 37 General Gravel Road " Management Plan 10 Woss Special Overview Map - Jan. -

Sailing Directions (Enroute)

PUB. 154 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ BRITISH COLUMBIA ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Bethesda, Maryland © COPYRIGHT 2007 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2007 TENTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 Preface 0.0 Pub. 154, Sailing Directions (Enroute) British Columbia, 0.0NGA Maritime Domain Website Tenth Edition, 2007, is issued for use in conjunction with Pub. http://www.nga.mil/portal/site/maritime 120, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) Pacific Ocean and 0.0 Southeast Asia. Companion volumes are Pubs. 153, 155, 157, 0.0 Courses.—Courses are true, and are expressed in the same 158, and 159. manner as bearings. The directives “steer” and “make good” a 0.0 Digital Nautical Chart 26 provides electronic chart coverage course mean, without exception, to proceed from a point of for the area covered by this publication. origin along a track having the identical meridianal angle as the 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 21 July 2007, includ- designated course. Vessels following the directives must allow ing Notice to Mariners No. 29 of 2007. for every influence tending to cause deviation from such track, and navigate so that the designated course is continuously Explanatory Remarks being made good. 0.0 Currents.—Current directions are the true directions toward 0.0 Sailing Directions are published by the National Geospatial- which currents set. -

First Nations Examples

First Nations Policy This document includes examples of First Nations’ developed consultation policies, agreements and protocols. First Nation Consultation Policy: A Consultation Policy developed by X First Nation. Cultural Heritage Policy: This policy applies to all activities that may impact the cultural heritage resources of the X First Nation. Consultation Process and Cultural Heritage Policy: A Consultation Process and Cultural Heritage Policy developed by X First Nation Cultural Heritage Investigation Permit: A useful template regarding stewardship of archaeological resources, includes a heritage policy. Cultural Heritage Investigation Permit Application: An application form to be used with the above Permit. Service Agreement: Between a First Nation and a Forestry Company outlining the costs paid to First Nations for participation in the referrals process. Memorandum of Understanding regarding land use and management planning: LRMP agreement between a First Nation and the Provincial Government that recognizes a government to government relationship. Memorandum of Understanding regarding oil and gas development: A MOU developed by a Treaty 8 First Nation regarding consultation on oil and gas development. Interim Measures Agreement (Forestry): An interim measures agreement negotiated through the treaty process regarding forestry and capacity building funding. If you have any questions, comments or other materials you think we should include, please contact : The Aboriginal Mapping Network (c/o The Sliammon First Nation: Ecotrust Canada): Phone: (604) 483-9646 Phone: (604) 682-4141, extension 240 E-mail: [email protected] This should NOT be considered legal advice. Readers should not act on information in the website without first seeking specific legal advice on the particular matters which are of concern to them. -

Fish Habitat Restoration Designs for Chalk Creek, Located in the Nahwitti River Watershed

FISH HABITAT RESTORATION DESIGNS FOR CHALK CREEK, LOCATED IN THE NAHWITTI RIVER WATERSHED Prepared for: Tom Cole, RPF Richmond Plywood Corporation 13911 Vulcan Way Richmond, B.C. V6V 1K7 MARCH 2004 Prepared by: Box 2760 · Port Hardy, B.C. · V0N 2P0 Chalk Creek Fish Habitat Restoration Designs TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction............................................................................................................. 3 2.0 Assessment Methods............................................................................................... 4 3.0 Hydrology ............................................................................................................... 4 4.0 Impact History and Restoration Objectives ............................................................ 6 5.0 Fish Habitat Prescriptions....................................................................................... 6 5.1 Alcove Modification ........................................................................................... 6 5.2 Access, Logistics, Materials and Labour ............................................................ 8 5.3 Fish Habitat Construction Timing Windows .................................................... 10 5.4 Timing of Works, Priorities and Scheduling .................................................... 10 5.5 Construction Monitoring and Environmental Controls .................................... 11 6.0 Literature Cited. ................................................................................................... -

Development Application

REGIONAL DISTRICT OF MOUNT WADDINGTON STAFF REPORT DATE: July 14, 2021 RDMW FILE: 2021-ZBA-01 TO: Regional Planning Committee FROM: Jeff Long, Manager of Planning & Development Services RE: DEVELOPMENT APPLICATION - ZONING BYLAW AMENDMENT: TLOWITSIS FIRST NATION C/O BERNIE TAEKEMA, PROPOSED FINFISH AQUACULTURE OPERATION IN CHATHAM CHANNEL, ELECTORAL AREA ‘A’ APPLICANT: Tlowitsis First Nation C/O Bernie Taekema, Taekema Consulting Inc. (consultant) ASSESSMENT ROLL NUMBER: not applicable PARCEL IDENTIFIER NUMBER: not applicable LEGAL DESCRIPTION: Crown land covered by water being part of the bed of Chatham Channel, Coast District OFFICIAL COMMUNITY PLAN: Regional Plan Bylaw No. 890, 2015 ZONING BYLAW: Regional District of Mount Waddington Zoning Bylaw No. 21, 1972 PURPOSE The Regional District of Mount Waddington (hereafter “RDMW”) is in receipt of a Development Application submission on behalf of the Tlowitsis Nation, by its consultant and agent, Bernie Taekema (hereafter “Applicant”), to request consideration of a zoning bylaw amendment with respect to an 85.6 hectare Crown land marine site (hereafter “subject property”) located adjacent to the mainland on the west side of Chatham Channel east of Minstrel island in Electoral Area ‘A’ (see location maps on pages 3 and 4). The subject property is currently included in the Marine Zone (MAR-1) in accordance with RDMW Zoning Bylaw No. 21 and the request is to change the applicable zoning category to permit finfish aquaculture. This initiative is part of a partnership agreement that the Tlowitsis Nation has with Grieg Seafood BC Ltd. to establish and operate a finfish aquaculture facility at this location. REGULATORY JURISDICTION Part 14 - Planning and Land Use Management of the Local Government Act addresses local governments’ roles regarding zoning bylaws. -

Hail the Columbia III

Hail the Columbia III Toronto , Ontario , Canada Friday, June 20, 2008 TO VANCOUVER AND BEYOND: About a year earlier, my brother Peter and his wife Lynn, reported on a one-of-a-kind cruise adventure they had in the Queen Charlotte Strait area on the inside passage waters of British Columbia. Hearing the stories and seeing the pictures with which they came back moved us to hope that a repeat voyage could be organized. And so we found ourselves this day on a WestJet 737 heading for Vancouver. A brief preamble will help set the scene: In 1966 Peter and Lynn departed the civilization of St. Clair Avenue in Toronto, for the native community of Alert Bay, on Cormorant Island in the Queen Charlotte Strait about 190 miles, as the crow flies, north-west of Vancouver. Peter was a freshly minted minister in the United Church of Canada and an airplane pilot of some experience. The United Church had both a church and a float-equipped airplane in Alert Bay. A perfect match. The purpose of the airplane was to allow the minister to fly to the something over 150 logging camps and fishing villages that are within a couple hundred miles of Alert Bay and there to do whatever it is that ministers do. This was called Mission Service. At the same time the Anglican Church, seeing no need to get any closer to God than they already were, decided to stay on the surface of the earth and so Horseshoe Bay chugged the same waters in a perky little ship. -

Regional Visitors Map Highlighting Parks, Trails and and Trails Parks, Highlighting Map Visitors Regional Large

www.sointulacottages.com www.northcoastcottages.ca www.umista.ca www.vancouverislandnorth.cawww.alertbay.ca www.porthardy.travel • www.ph-chamber.bc.ca • www.porthardy.travel P: 250-974-5403 P: 250-974-5024 P: P: 250-973-6486 P: Regional Features [email protected] 1-866-427-3901 TF: • 250-949-7622 P: 1 Front Street, Alert Bay, BC Bay, Alert Street, Front 1 BC Bay, Alert Street, Fir 116 Sointula, BC Sointula, Port Hardy, BC • P: 250-902-0484 P: • BC Hardy, Port 7250 Market St, Port Hardy, BC Hardy, Port St, Market 7250 40 Hiking Trail Mateoja Trail Adventure! the Park Boundary Culture Bere Point Regional Park & Campsite 8 The 6.4 km round-trip Mateoja Heritage Trail begins on Live and us visit Come hiking. & diving Cliffs To Hwy 19 There are 24 campsites nestled in the trees with the beach just 3rd Street above the town site. Points of interest include Boulderskayaking, fishing, beaches, splendid 1-888-956-3131 • www.portmcneill.net • 1-888-956-3131 A natural paradise! Abundant wildlife, wildlife, Abundant paradise! natural A [email protected] • winterharbourcottages.com • [email protected] the Mateoja farm site, an early 1900’s homestead, Little Cave with Horizontal Entrance Port McNeill, BC • P: 250-956-3131 P: • BC McNeill, Port a stone’s throw away, where250-969-4331 P: • youBC can enjoyHarbour, viewsWinter across Queen Cave with Vertical Entrance Charlotte Strait to the nearby snow-capped coast mountains. Lake, marshland at Melvin’s Bog, Duck Ponds and the local SOINTULA swimming hole at Big Lake. Decks and benches along the Parking This Park is within steps of the Beautiful Bay trailhead, and is a “Fern” route are ideal for picnics and birdwatchers. -

Tlatlasikwala

Statement of Intent Tlatlasikwala 1. What is the First Nation Called? Tlatlasikwala Nation 2. How is the First Nation established? Please Describe: Custom band with a Hereditary Chief and appointed Council. Is there an attachment? No 3. Who are the aboriginal people represented by the First Nation? Tlatlasikwala and the Nakumgalisala Peoples 4. How many aboriginal people are represented by the First Nation? Approx. 39 Is there any other First Nation that claims to represent the aboriginal people described in questions 3 and 4? If so, please list. 5. Please list any First Nations with whom the First Nation may have overlapping or shared territory. Quatsino First Nation and Kwakiutl First Nation 6. What is the First Nation's traditional territory in BC? Traditional Territories from the west coast of Vancouver Island from Sea Otter Cove and its adjacent waters to and including Triangle Island to a south-easterly direction, to Pine Island, down to a south-easterly course to the Gordon Islands and back across to Sea Otter Cove; inclusive of the rivers, head-waters and lakes across this stretch of land east to west as earlier identified. The Tlatlasikwala Traditional Territory Map may be updated in the future. Attach a map or other document, if available or describe. Map Available? Yes 7. Is the First Nation mandated by its constituents to submit a Statement of Intent to negotiate a treaty with Canada and British Columbia under the treaty process? Yes How did you receive your Mandate? (Please provide documentation) The Tlatlasikwala Council received its mandate to enter treaty negotiations by personally contacting its members living in Vancouver, Port Coquitlam, Kamloops, Kelowna, Whe-La-La-u (Alert Bay) Quatsino and Bella Bella for their approval. -

Regional Visitors Map

Regional Visitors Map www.vancouverislandnorth.ca Boomer Jerritt - Sandy beach at San Josef Bay BC Ferries Discovery Coast Port Hardy - Prince RupertBC Ferries Inside Passage Port Hardy - Bella Coola Wakeman Sound www.bcbudget.com Mahpahkum-Ahkwuna Nimmo Bay Kingcome Deserters-Walker Kingcome Inlet 1-888-368-7368 Hope Is. Conservancy Drury Inlet Mackenzie Sound Upper Blundon Sullivan Kakwelken Harbour Bay Lake Cape Sutil Nigei Is. Shuttleworth Shushartie North Kakwelken Bight Bay Goletas Channel Balaclava Is. Broughton Island God’s Pocket River Christensen Pt. Nahwitti River Water Taxi Access (privately operated) Wishart Kwatsi Bay 24 Provincial Park Greenway Sound Peninsula Strandby River Strandby Shushartie Saddle Hurst Is. Bond Sd Nissen 49 Nels Bight Queen Charlotte Strait Lewis Broughton Island Knob Hill Duncan Is. Cove Tribune Channel Mount Cape Scott Bight Doyle Is. Hooper Viner Sound Hansen Duval Is. Lagoon Numas Is. Echo Bay Guise Georgie L. Bay Eden Is. Baker Is. Marine Provincial Thompson Sound Cape Scott Hardy William L. 23 Bay 20 Provincial Park PORT Peel Is. Brink L. HARDY 65 Deer Is. 15 Nahwitti L. Kains L. 22 Beaver Lowrie Bay 46 Harbour 64 Bonwick Is. 59 Broughton Gilford Island Tribune ChannelMount Cape 58 Woodward 53 Archipelago Antony 54 Fort Rupert Health Russell Nahwitti Peak Provincial Park Bay Mountain Trinity Bay 6 8 San Josef Bay Pemberton 12 Midusmmer Is. HOLBERG Hills Knight Inlet Quatse L. Misty Lake Malcolm Is. Cape 19 SOINTULA Lady Is. Ecological 52 Rough Bay 40 Blackfish Sound Palmerston Village Is. 14 COAL Reserve Broughton Strait Mitchell Macjack R. 17 Cormorant Bay Swanson Is. Mount HARBOUR Frances L. -

Regional Report on the Status of Pacific Salmon

The status of Pacific salmon in the Broughton Archipelago, northeast Vancouver Island, and mainland inlets A report from © Salmon Coast Field Station 2020 Salmon Coast Field Station is a charitable society and remote hub for coastal research. Established in 2001, the Station supports innovative research, public education, community outreach, and ecosystem awareness to achieve lasting conservation measures for the lands and waters of the Broughton Archipelago and surrounding areas. General Delivery, Simoom Sound, BC V0P 1S0 Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw territory [email protected] | www.salmoncoast.org Station Coordinators: Amy Kamarainen & Nico Preston Board of Directors: Andrew Bateman, Martin Krkošek, Alexandra Morton, Stephanie Peacock, Scott Rogers Cover photo: Jordan Manley Photos on pages 30, 38: April Bencze Suggested citation: Atkinson, EM, CE Guinchard, AM Kamarainen, SJ Peacock & AW Bateman. 2020. The status of Pacific salmon in the Broughton Archipelago, northeast Vancouver Island, and mainland inlets. A report from Salmon Coast Field Station. Available from www.salmoncoast.org 1 Status of Pacific Salmon in Area 12 | For the salmon How are you, salmon? Few fish, but glimmers of hope Sparse data, blurred lens 2 Status of Pacific Salmon in Area 12 | For the salmon Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................... 4 Motivation & Background ................................................................................................. 5 The -

VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, and COLONIALISM on the NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA a THESIS Pres

“OUR PEOPLE SCATTERED:” VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, AND COLONIALISM ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA A THESIS Presented to the University of Oregon History Department and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ian S. Urrea Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the History Department by: Jeffrey Ostler Chairperson Ryan Jones Member Brett Rushforth Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2019 ii © 2019 Ian S. Urrea iii THESIS ABSTRACT Ian S. Urrea Master of Arts University of Oregon History Department September 2019 Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846” This thesis interrogates the practice, economy, and sociopolitics of slavery and captivity among Indigenous peoples and Euro-American colonizers on the Northwest Coast of North America from 1774-1846. Through the use of secondary and primary source materials, including the private journals of fur traders, oral histories, and anthropological analyses, this project has found that with the advent of the maritime fur trade and its subsequent evolution into a land-based fur trading economy, prolonged interactions between Euro-American agents and Indigenous peoples fundamentally altered the economy and practice of Native slavery on the Northwest Coast.