Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Bush and the End of the Cold War. Christopher Alan Maynard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 From the Shadow of Reagan: George Bush and the End of the Cold War. Christopher Alan Maynard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Maynard, Christopher Alan, "From the Shadow of Reagan: George Bush and the End of the Cold War." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 297. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/297 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fiims the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Matlock Episode Guide

Matlock episode guide Continue (Titles and Air Dates Guide) Last updated: Fri, 9 Oct 2020 -1:00 Episode list - details from: TVmaze and TV.com Available videos appear here - Powered by JustWatch Season 9 Season 8 Season 7 Season 6 Season 5 Season 3 Season 2 Season 2 Wikipedia Article List Matlock is an American TV drama, starred Andy Griffith, who ran from March 3, 1986 to May 8, 1992 on NBC and from November 5, 1992 to May 4, 1995 on ABC. A total of nine seasons and 194 episodes were released. Series overview SeasonEpisodesOriginally airedRankRatingFirst airedLast airedNetworkPilot1March 3, 1986 (1986-03-03)NBCN/AN/A123September 23, 1986 (1986-09-23)May 12, 1987 (1987-05-12)1518.6224September 22, 1987 (1987-09-22)May 3, 1988 (1988-05-03)1417.8320November 29, 1988 (1988-11-29)May 16, 1989 (1989-05-16)1217.7424September 19, 1989 (1989-09-19)May 8, 1990 (1990-05- 08)2016.6522September 18, 1990 (1990-09-18)April 30, 1991 (1991-04-30)1715.5622October 18, 1991 (1991-10-18)May 8, 1992 (1992-05-08)N/AN/A718November 5, 1992 (1992-11-05)May 6, 1993 (1993-05-06)ABC2813.3822September 23, 1993 (1993-09-23)May 19, 1994 (1994-05- 19)N/AN/A918October 13, 1994 (1994-10-13)May 7, 1995 (1995-05-07)N/AN/A Episodes Pilot (1986) Actor Character Andy Griffith Ben Matlock Lori Lethin Charlene Matlock Alice Hirson Hazel Kene Holliday Tyler Hudson Title Directed by Written by Original air date Diary of a Perfect MurderRobert DayDean HargroveMarch 3 , 1986 (1986-03-03) Ben Matlock (Andy Griffith) and his daughter Charlene (Lori Letin) defend TV journalist Steve Emerson (Steve Inwood), who is accused of murdering Linda Coolidge (Katherine Cannon), his ex-wife. -

The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture

9 The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture A Cosmological Expression Anna Sofaer TUDIES BY THE SOLSTICE PROJECT indicate that the solar-and-lunar regional pattern that is symmetri- Smajor buildings of the ancient Chacoan culture cally ordered about Chaco Canyon’s central com- of New Mexico contain solar and lunar cosmology plex of large ceremonial buildings (Sofaer, Sinclair, in three separate articulations: their orientations, and Williams 1987). These findings suggest a cos- internal geometry, and geographic interrelation- mological purpose motivating and directing the ships were developed in relationship to the cycles construction and the orientation, internal geome- of the sun and moon. try, and interrelationships of the primary Chacoan From approximately 900 to 1130, the Chacoan architecture. society, a prehistoric Pueblo culture, constructed This essay presents a synthesis of the results of numerous multistoried buildings and extensive several studies by the Solstice Project between 1984 roads throughout the eighty thousand square kilo- and 1997 and hypotheses about the conceptual meters of the arid San Juan Basin of northwestern and symbolic meaning of the Chacoan astronomi- New Mexico (Cordell 1984; Lekson et al. 1988; cal achievements. For certain details of Solstice Pro- Marshall et al. 1979; Vivian 1990) (Figure 9.1). ject studies, the reader is referred to several earlier Evidence suggests that expressions of the Chacoan published papers.1 culture extended over a region two to four times the size of the San Juan Basin (Fowler and Stein Background 1992; Lekson et al. 1988). Chaco Canyon, where most of the largest buildings were constructed, was The Chacoan buildings were of a huge scale and the center of the culture (Figures 9.2 and 9.3). -

Ancient Maize from Chacoan Great Houses: Where Was It Grown?

Ancient maize from Chacoan great houses: Where was it grown? Larry Benson*†, Linda Cordell‡, Kirk Vincent*, Howard Taylor*, John Stein§, G. Lang Farmer¶, and Kiyoto Futaʈ *U.S. Geological Survey, Boulder, CO 80303; ‡University Museum and ¶Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; §Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department, Chaco Protection Sites Program, P.O. Box 2469, Window Rock, AZ 86515; and ʈU.S. Geological Survey, MS 963, Denver Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225 Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved August 26, 2003 (received for review August 8, 2003) In this article, we compare chemical (87Sr͞86Sr and elemental) analyses of archaeological maize from dated contexts within Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, to potential agricul- tural sites on the periphery of the San Juan Basin. The oldest maize analyzed from Pueblo Bonito probably was grown in an area located 80 km to the west at the base of the Chuska Mountains. The youngest maize came from the San Juan or Animas river flood- plains 90 km to the north. This article demonstrates that maize, a dietary staple of southwestern Native Americans, was transported over considerable distances in pre-Columbian times, a finding fundamental to understanding the organization of pre-Columbian southwestern societies. In addition, this article provides support for the hypothesis that major construction events in Chaco Canyon were made possible because maize was brought in to support extra-local labor forces. etween the 9th and 12th centuries anno Domini (A.D.), BChaco Canyon, located near the middle of the high-desert San Juan Basin of north-central New Mexico (Fig. -

A Navajo Myth from the Chaco Canyon Gretchen Chapin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Mexico New Mexico Anthropologist Volume 4 | Issue 4 Article 4 12-1-1940 A Navajo Myth From the Chaco Canyon Gretchen Chapin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_anthropologist Recommended Citation Chapin, Gretchen. "A Navajo Myth From the Chaco Canyon." New Mexico Anthropologist 4, 4 (1940): 63-67. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_anthropologist/vol4/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Anthropologist by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW MEXICO ANTHROPOLOGIST 63 from the Dominican monastery until 1575. The Real y Pontificia Universidad de Mexico lasted without much interruption until the period of the French Intervention. Then it was closed for many years; became the Universidad Nacional de Mexico in 1910; and in 1929 was chartered as the Universidad Nacional Aut6noma de Mexico.. The University of Lima became the Universidad Mayor de San Marcos de Lima in 1574, and has continued ever since, with major interruptions only during the War for Independence and again just a few years ago. In final summary one can say that, of the New World institutions of higher learning, the College of Santa Cruz was first founded and opened; the University of Michoacin has had the longest history; the University of Lima probably has been open the most years, has been at her present site longest, and has retained present form of name longest; and the University of Mexico has had the greatest number of students, graduates, and faculty members and was the first to actually open of the formally constituted universities. -

National Journalism Awards

George Pennacchio Carol Burnett Michael Connelly The Luminary The Legend Award The Distinguished Award Storyteller Award 2018 ELEVENTH ANNUAL Jonathan Gold The Impact Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB CBS IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY CAROL BURNETT. YOUR GROUNDBREAKING CAREER, AND YOUR INIMITABLE HUMOR, TALENT AND VERSATILITY, HAVE ENTERTAINED GENERATIONS. YOU ARE AN AMERICAN ICON. ©2018 CBS Corporation Burnett2.indd 1 11/27/18 2:08 PM 11TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards Los Angeles Press Club Awards for Editorial Excellence in A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 2017 and 2018, Honorary Awards for 2018 6464 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 870 Los Angeles, California 90028 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (310) 464-3577 E-mail: [email protected] Carper Du;mage Website: www.lapressclub.org Marie Astrid Gonzalez Beowulf Sheehan Photography Beowulf PRESS CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT: Chris Palmeri, Bureau Chief, Bloomberg News VICE PRESIDENT: Cher Calvin, Anchor/ Reporter, KTLA, Los Angeles TREASURER: Doug Kriegel, The Impact Award The Luminary The TV Reporter For Journalism that Award Distinguished SECRETARY: Adam J. Rose, Senior Editorial Makes a Difference For Career Storyteller Producer, CBS Interactive JONATHAN Achievement Award EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus GOLD International Journalist GEORGE For Excellence in Introduced by PENNACCHIO Storytelling Outside of BOARD MEMBERS Peter Meehan Introduced by Journalism Joe Bell Bruno, Freelance Journalist Jeff Ross MICHAEL Gerri Shaftel Constant, CBS CONNELLY CBS Deepa Fernandes, Public Radio International Introduced by Mariel Garza, Los Angeles Times Titus Welliver Peggy Holter, Independent TV Producer Antonio Martin, EFE The Legend Award Claudia Oberst, International Journalist Lisa Richwine, Reuters For Lifetime Achievement and IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY Ina von Ber, US Press Agency Contributions to Society CAROL BURNETT. -

The Chaco Phenomenon

The Chaco CROW CANYON Phenomenon ARCHAEOLOGICAL CENTER September 24–30, 2017 ITINERARY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 24 Arrive in Durango, Colorado, by 4 p.m. Meet the group for dinner and program orientation. Our scholar, Erin Baxter, Ph.D., provides an overview of the movements of Chaco culture, as well as the latest research. Overnight, Durango. D MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 25 Drive south to Chaco Culture National Historical Park, in the high desert of what is now northern New Mexico. From about A.D. 900 to 1150, Chaco Canyon was the center of a vast regional system that integrated much of the Pueblo world. Our Chaco Canyon exploration begins with the great houses of “downtown” Chaco. At Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito, we examine the architectural features that define great houses and discuss current theories about their function in the community. With the transformation of Pueblo Bonito into the largest of all great houses, some believe Chaco Canyon became the center of the ancestral Pueblo world. We meander along the cliffs on the north side of the canyon, searching for rock art. Overnight, camping under the stars, Chaco Canyon. B L D TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 26 This morning we explore the great houses, great kivas, and small house sites of Tsin Kletsin in Chaco Canyon (2.5 mile round-trip hike, 450-foot Chetro Ketl elevation change). We also visit Casa Rinconada and associated small house sites. Though small house sites are contemporaneous with great houses, the architecture differs markedly, and we discuss the meaning of these differences. After some time at the visitor center, we take the short hike to Una Vida and nearby rock art. -

The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon

The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon Chaco Matters An Introduction Stephen H. Lekson Chaco Canyon, in northwestern New Mexico, was a great Pueblo center of the eleventh and twelfth centuries A.D. (figures 1.1 and 1.2; refer to plate 2). Its ruins represent a decisive time and place in the his- tory of “Anasazi,” or Ancestral Pueblo peoples. Events at Chaco trans- formed the Pueblo world, with philosophical and practical implications for Pueblo descendents and for the rest of us. Modern views of Chaco vary: “a beautiful, serene place where everything was provided by the spirit helpers” (S. Ortiz 1994:72), “a dazzling show of wealth and power in a treeless desert” (Fernandez-Armesto 2001:61), “a self-inflicted eco- logical disaster” (Diamond 1992:332). Chaco, today, is a national park. Despite difficult access (20 miles of dirt roads), more than seventy-five thousand people visit every year. Chaco is featured in compendiums of must-see sights, from AAA tour books, to archaeology field guides such as America’s Ancient Treasures (Folsom and Folsom 1993), to the Encyclopedia of Mysterious Places (Ingpen and Wilkinson 1990). In and beyond the Southwest, Chaco’s fame manifests in more substantial, material ways. In Albuquerque, New Mexico, the structure of the Pueblo Indian Cultural COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 3 Stephen H. Lekson Figure 1.1 The Chaco region. Center mimics precisely Pueblo Bonito, the most famous Chaco ruin. They sell Chaco (trademark!) sandals in Paonia, Colorado, and brew Chaco Canyon Ale (also trademark!) in Lincoln, Nebraska. The beer bottle features the Sun Dagger solstice marker, with three beams of light striking a spiral petroglyph, presumably indicating that it is five o’clock somewhere. -

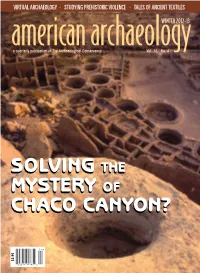

Solving the Mystery of Chaco Canyon?

VIRTUALBANNER ARCHAEOLOGY BANNER • BANNER STUDYING • BANNER PREHISTORIC BANNER VIOLENCE BANNER • T •ALE BANNERS OF A NCIENT BANNER TEXTILE S american archaeologyWINTER 2012-13 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 SOLVINGSOLVING THETHE MYMYSSTERYTERY OFOF CHACHACCOO CANYONCANYON?? $3.95 $3.95 WINTER 2012-13 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 26 CHACO, THROUGH A DIFFERENT LENS BY MIKE TONER Southwest scholar Steve Lekson has taken an unconventional approach to solving the mystery of Chaco Canyon. 12 VIRTUALLY RECREATING THE PAST BY JULIAN SMITH Virtual archaeology has remarkable potential, but it also has some issues to resolve. 19 A ROAD TO THE PAST BY ALISON MCCOOK A dig resulting from a highway project is yielding insights into Delaware’s colonial history. 33 THE TALES OF ANCIENT TEXTILES BY PAULA NEELY Fabric artifacts are providing a relatively new line of evidence for archaeologists. 39 UNDERSTANDING PREHISTORIC VIOLENCE BY DAN FERBER Bioarchaeologists have gone beyond studying the manifestations of ancient violence to examining CHAZ EVANS the conditions that caused it. 26 45 new acquisition A TRAIL TO PREHISTORY The Conservancy saves a trailhead leading to an important Sinagua settlement. 46 new acquisition NORTHERNMOST CHACO CANYON OUTLIER TO BE PRESERVED Carhart Pueblo holds clues to the broader Chaco regional system. 48 point acquisition A GLIMPSE OF A MAJOR TRANSITION D LEVY R Herd Village could reveal information about the change from the Basketmaker III to the Pueblo I phase. RICHA 12 2 Lay of the Land 50 Field Notes 52 RevieWS 54 Expeditions 3 Letters 5 Events COVER: Pueblo Bonito is one of the great houses at Chaco Canyon. -

Allen S. Facemire

Allen S. Facemire Director/Director of Photography FEATURE & TV CREDITS COMPANY PRODUCTION MGR. JOB CLASSIFICATION Moonrunners United Artist Peter Cornberg 2nd Unit DP/Operator Born to Kill New World Peter Cornberg 2nd Unit DP/Operator Greased Lightning Universal Lester Berman 2nd Camera Operator Dukes of Hazzard Warner Bros. Al Salzer 2nd UnitDP/Operator Black Beauty(TV) Universal Jack Stubbs 1st Camera Operator Buddy Holly Story Columbia Don Gold 2nd Unit DP/Operator Honeysuckle Rose Universal 2nd Camera Operator Breaking Away(TV) 20th Century Fox 2nd Camera Operator Sheriff Lobo(TV) Universal Joe Swerling Title sequence DP Stripes Columbia Russ Saunders 2nd camera operator Under the Rainbow Orion Don Gold 2nd Unit DP/Operator Six Pack(TV Pilot) NBC Productions Leonard Smith 1st Operator Hobson's Choice CBS Al Salzer 1st Operator Getting Even AGH Films Jean Higgins 2nd Unit DP/OperatorAerial DP/Operator Miami Vice(TV) NBC Sly Lovegrin 2nd Camera Operator Matlock(TV) NBC Jeff Peters Atlanta 2nd Unit DP Heat of the Night MGM-TV Ed Ledding 1st Camera Operator Shy People Cannon Films Michael Fottrell 2nd Unit DP/operator Grass Roots Aaron/Spelling Dereck Kavenaugh lst Operator Savannah Aaron/Spelling 2nd Unit DP/Operator special segment) Passing Glory TNT Productions Bill Butler-DP 2nd camera operator Safe Harbor Aaron/Spelling Dean Norris of the WB Aerial DP Fresh From the Garden DIY SaltRun Productions, inc. Director/DP Ground Breakers HGTV SaltRun Productions, inc. Director/DP NETWORK TELEVISION ABC News NBC News HBO Entertainment NOVA ABC Sports NBC Sports COPS Turner Disney Channel SHOWTIME MTV IBM 20/20 Major League Baseball MOTOR TREND Ringling Bros. -

Texas Justice Court Training Center Southwest Texas State University San Marcos, Texas 78666 ~~ Telephone: (512) 245-2349

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. TEXAS JUSTICE COURT DIRECTORY - ~ TEXAS JUSTICE COURT TRAINING CENTER SOUTHWEST TEXAS STATE UNIVERSITY SAN MARCOS, TEXAS 78666 ~~ TELEPHONE: (512) 245-2349 1977 --------------------------------- TEXAS JUSTICE COURT DIRECTORY 1977 TEXAS JUSTICE COURT TRAINING CENTER SOUTHWEST TEXAS STATE UNIVERSITY SAN MARCOS J TEXAS 78666 (512) 245-2349 TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY .•....•.••••.••.••.•..•. " . ., . • . • • • . •• IV FOREWARD •••• - • • • • • • • • • • • • .. • .. • • • • • • • • • • • V TRAINING CENTER STAFF .................•VIII BOARD OF DIRECTORS..................... IX JUSTICES OF THE PEACE.................. 1 ALPHABETICAL COUNTY LIST ............... 48 ALPHABETICAL CITY LIST/ COUNTY CROSS RE1'"'ERENCE............... 50 III KEY ANDERSON- county ~precinct and Place Office PeT. 1.1 PL. 1 (214) 729-2896- Telephone HON. CHARLIE C. LEE - Name '74 \ Date Assumed 308 HAMILTON RD. __ Office ~ Mailing Address PALESTINEJ TEXAS 75801 Counties are listed in alphabetical order. County name will be followed by Justices of the Peace who serve that county from lowest to highest precinct numbers. To find the county in which a city is located, turn to page 50 for an alphabetical listing of cities with county cross reference. IV -----~-- ttI).fI~""",· • .,. ..'" ,~ ...... FORa~ARD N C J R 5 " HISTORY OF THE OFFICE OF JUSTICE OF THE PEACE " APR 1 51~77 The office of Justice o~ the Peace was establish ed in 1362 A. D. by King Edward.tfJ:.I,.A~ ~p,,9..1,.<!p.d. ...Tf>A,. office of Justice of the Peace ~~~~~ll"&~ pleting the centralization of government in England. The office of Justice of the Peace is an integral part of the AnglO-American system of jurisprudence. For three hundred years, the English Justices of the Peace contributed immeasurably, through police, administrative and judicial functions, to the final supremacy of the lawmaking body of England. -

2018 Ancient Pueblo and Rock Art Tour

Ancient Pueblos and Rock Art of New Mexico Tour The Ancient Pueblos and Rock Art of New Mexico Tour from Monday, May 7, 2018 through Friday, May 18, 2018 was the major Society tour for the year. Twenty-nine members participated. The tour started in Albuquerque with a side trip to Acoma Sky City, the oldest continuously inhabited community in North America. In Albuquerque the group visited three rock art sites in Petroglyph National Monument and the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology. We were fortunate to visit the archives of the Maxwell Museum where pottery abounded. Lunch was enjoyed at Church Street Café in Old Town Albuquerque. Group at Acoma Sky City* Rinconada Canyon Rock Art – animal, bird *Photos provided by Jan Johansen Boca Negra Rock Art – birds +, macaw and cage Piedras Marcadas Canyon Rock Art From Albuquerque the group went to the Gallina region and enjoyed tours of Nogales Cliff House Trail, Huerfano Mesa and Rattlesnake Ridge. Three archaeologists from the U.S. Forest Service led the groups to the sites and painted a picture of life in the area from approximately 1050 to 1300 BP. Nogales Pueblo Ruins Huerfano Mesa Rattlesnake Tower Chaco Canyon was the next destination. The highlighted tour was conducted by an archaeologist from San Juna County Research Center and Library at Salmon Ruins,. The one-day tour consisted of a van ride from Bloomfield to Chaco Canyon, lunch and a guided walk through Hungo Pavi, Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito. Some of the group returned for a second day of touring to visit other ruins.