Foucault, Michel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Governmentality

ARTICLE IN PRESS + MODEL Political Geography xx (2006) 1e5 www.elsevier.com/locate/polgeo Rethinking governmentality Stuart Elden* Department of Geography, Durham University, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE, United Kingdom On 1st February 1978 at the Colle`ge de France, Michel Foucault gave the fourth lecture of his course Se´curite´, Territoire, Population [Security, Territory, Population]. This lecture, which became known simply as ‘‘Governmentality’’, was first published in Italian, and then in English in the journal Ideology and Consciousness in 1979. In 1991 it was reprinted in The Foucault Effect, a collection which brought together work by Foucault and those inspired by him (Burch- ell, Gordon, & Miller, 1991). Developing from this single lecture has been a veritable cottage industry of material, across the social sciences, including geography, of ‘governmentality studies’. In late 2004 the full lecture course and the linked course from the following year were pub- lished by Seuil/Gallimard as Se´curite´, Territoire, Population: Cours au Colle`ge de France (1977e1978) and Naissance de la biopolitique: Cours au Colle`ge de France (1978e1979) [The Birth of Biopolitics]. The lectures were edited by Michel Senellart, and the publication was timed to coincide with the 20th anniversary of Foucault’s death. They are currently being translated into English by Graham Burchell, and we publish an excerpt from the first lecture of the Security, Territory, Population course here. Given the interest of geographers in the notion of governmentality, the publication of the lectures is likely to have a significant impact. The concept of governmentality has produced a range of important studies, including those in a range of disciplines (see, for example, Barry, Osborne, & Rose, 1996; Dean, 1999; Lemke, 1997; Senellart, 1995; Walters & Haahr, 2004; Walters & Larner, 2004) as well as some analyses from within geography (Braun, 2000; Cor- bridge, Williams, Srivastava, & Veron, 2005; Hannah, 2000; Huxley, 2007; Legg, 2006). -

Abs Stop Sign Mp3, Flac, Wma

Abs Stop Sign mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Pop Album: Stop Sign Country: Australia Released: 2003 Style: Europop, Breakbeat, Electro MP3 version RAR size: 1422 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1715 mb WMA version RAR size: 1422 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 892 Other Formats: RA FLAC APE AAC MOD MP2 XM Tracklist Hide Credits Stop Sign Arranged By [Arrangement Input By] – A. Harrison*, G. Simmons*Backing Vocals – 1 Tracy AckermanMixed By – Absolute , Steve FitzmauriceProducer, Instruments [All 2:56 Instruments] – Absolute Written-By – Watkins*, O'Connell*, Sechleer*, Wynn*, Wilson*, Breen* Music For Cars Backing Band – Abs Backing Vocals – Richard "Biff" Stannard*Mixed By – Alvin 2 SweeneyProducer – Alvin Sweeney, Julian Gallagher, Richard "Biff" 3:02 Stannard*Programmed By – Julian GallagherWritten-By – Alvin Sweeney, Julian Gallagher, R. Breen*, Richard "Biff" Stannard* Stop That Bitchin' Backing Vocals – Shernette MayMixed By – Alvin SweeneyProducer, Instruments [All 3 Instruments] – Julian Gallagher, Richard "Biff" Stannard*Programmed By – Alvin 3:16 Sweeney, Julian Gallagher, Richard "Biff" Stannard*Written-By – Julian Gallagher, R. Breen*, Richard "Biff" Stannard* Video Stop Sign Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – BMG UK & Ireland Ltd. Copyright (c) – BMG UK & Ireland Ltd. Licensed From – Nestshare Ltd. Manufactured By – BMG Australia Limited Distributed By – BMG Australia Limited Pressed By – Technicolor, Australia Produced For – Biffco Productions Mixed At – Biffco Studios, Dublin Published -

Governing Circulation: a Critique of the Biopolitics of Security

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Governing circulation: A critique of the biopolitics of security Book Section How to cite: Aradau, Claudia and Blanke, Tobias (2010). Governing circulation: A critique of the biopolitics of security. In: de Larrinaga, Miguel and Doucet, Marc G. eds. Security and Global Governmentality: Globalization, Governance and the State. London: Routledge. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2010 Routledge Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415560580/ Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Governing circulation: a critique of the biopolitics of security Claudia Aradau (Open University) and Tobias Blanke (King’s College London) Suggested quotation: Claudia Aradau and Tobias Blanke (2010), ‘Governing Circulation: a critique of the biopolitics of security’ in Miguel de Larrinaga and Marc Doucet (eds), Security and Global Governmentality: Globalization, Power and the State (Basingstoke: Palgrave), pp. 44-58. Michel Foucault’s lectures at the Collège de France on Security, Territory, Population and The Birth of Biopolitics have offered new ways of thinking the transformation of power relations and security practices from the 18 th century on in Europe. While governmental technologies and rationalities had already been aptly explored to understand the multiple ways in which power takes hold of lives to be secured and lives whose riskiness is to be neutralised (e.g. -

Said-Introduction and Chapter 1 of Orientalism

ORIENTALISM Edward W. Said Routledge & Kegan Paul London and Henley 1 First published in 1978 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. 39 Store Street, London WCIE 7DD, and Broadway House, Newton Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN Reprinted and first published as a paperback in 1980 Set in Times Roman and printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge & Esher © Edward W. Said 1978 No Part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passage in criticism. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Said, Edward W. Orientalism, 1. East – Study and teaching I. Title 950’.07 DS32.8 78-40534 ISBN 0 7100 0040 5 ISBN 0 7100 0555 5 Pbk 2 Grateful acknowledgements is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: Excerpts from Subject of the Day: Being a Selection of Speeches and Writings by George Nathaniel Curzon. George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: Excerpts from Revolution in the Middle East and Other Case Studies, proceedings of a seminar, edited by P. J. Vatikiotis. American Jewish Committee: Excerpts from “The Return of Islam” by Bernard Lewis, in Commentary, vol. 61, no. 1 (January 1976).Reprinted from Commentary by permission.Copyright © 1976 by the American Jewish Committee. Basic Books, Inc.: Excerpts from “Renan’s Philological Laboratory” by Edward W. Said, in Art, Politics, and Will: Essarys in Honor of Lionel Trilling, edited by Quentin Anderson et al. Copyright © 1977 by Basic Books, Inc. The Bodley Head and McIntosh & Otis, Inc.: Excerpts from Flaubert in Egypt, translated and edited by Franscis Steegmuller.Reprinted by permission of Francis Steegmuller and The Bodley Head. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

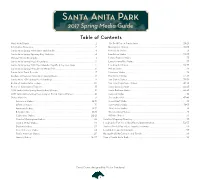

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Michel Foucault, Fearless Speech. Edited by Joseph Pearson. (Los Angeles: Semiotext(E), 2001), 183 Pages

BOOK REVIEWS 77 Michel Foucault, Fearless Speech. Edited by Joseph Pearson. (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2001), 183 pages. Andrew Knighton University of Minnesota In a 1986 conversation with Robert Maggiori (published in English in Negotiations, Columbia University Press, 1995), the French philosopher Gilles Delenze cautioned against regarding Michel Foucault as a sort of "intellectual guru." Instead, in defiance of a trend whose momentum has yet ceased to abate, he insists on situating Foucault in a larger conversation—with the theorists that were his contemporaries, with the problems in his work, and with himself. A Foucault lecture, then, is seen to resemble less a sermon than it does a concert—the performance of "a soloist 'accompanied' by everyone else." In spite of that caveat, Deleuze concludes, simply, that "Foucault gave wonderful lectures." This assertion of Foucault's oratorical acumen will surprise few who have read, for example, his inaugural lecture at the College de France in 1970 ("The Order of Discourse"). Even less surprising is that some of his lectures prove better than others. As we are reminded by the editor of Semiotext(e)'s Fearless Speech (a collection of talks delivered as part of a 1983 Berkeley seminar entitled "Discourse and Truth") these transcribed lectures do not reflect Foucault's notes or intentions, and, being published after his death, lack his imprimatur. And while this may partially account for their occasional flatness, they are further hindered by having to stand on their own, without the contextualization necessary to animate their themes. Fearless Speech can, however, come alive, if regarded as an index of a crucial turning point in the development of Foucault's thought. -

138904 09 Juvenilefilliesturf.Pdf

breeders’ cup JUVENILE FILLIES TURF BREEDERs’ Cup JUVENILE FILLIES TURF (GR. I) 6th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR FILLIES, TWO-YEARS-OLD ONE MILE ON THE TURF Weight, 122 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Al Thakhira (GB) Sheikh Joaan Bin Hamad Al Thani Marco Botti B.f.2 Dubawi (IRE) - Dahama (GB) by Green Desert - Bred in Great Britain by Qatar Bloodstock Ltd Chriselliam (IRE) Willie Carson, Miss E. Asprey & Christopher Wright Charles Hills B.f.2 Iffraaj (GB) - Danielli (IRE) by Danehill - Bred in Ireland by Ballylinch Stud Clenor (IRE) Great Friends Stable, Robert Cseplo & Steven Keh Doug O'Neill B.f.2 Oratorio (IRE) - Chantarella (IRE) by Royal Academy - Bred in Ireland by Mrs Lucy Stack Colonel Joan Kathy Harty & Mark DeDomenico, LLC Eoin G. -

Vente De Yearlings Mardi 19 Août Deauville

WOOTTON BASSETT 2014 2008 (IFFRAAJ ET BALLADONIA PAR PRIMO DOMINIE) GAGNANT DE GROUPE 1 ET INVAINCU À 2 ANS MEILLEUR 2 ANS FRANÇAIS DE SA GÉNÉRATION Vente de Yearlings Mardi 19 août Deauville Vente de Yearlings Vente Après la réussite aux ventes de ses premiers foals en 2013, ne manquez pas ses premiers yearlings en 2014, POUR PRÉPARER LES COURSES DE 2 ANS EN 2015 ! www.haras-etreham.fr La passion de l’élevage NICOLAS DE CHAMBURE : 06 24 27 06 42 FRANCK CHAMPION : 06 07 23 36 46 370 La Motteraye Consignment 370 Roberto Bob Back Toter Back BIG BAD BOB Marju (FR) Fantasy Girl N. Persian Fantasy Nureyev Peintre Célèbre M.b. 18/02/2013 RAFINE Peinture Bleue 2005 (GB) La Belga Roy 1998 La Baraca Qualifié F.E.E. - Breeders' Cup - Owners' Premiums in France BIG BAD BOB (2000), 8 vict., Furstenberg-Rennen (Gr.3), Prix Ridgway (L.), Autumn St.(L.), 2e Dee St.(Gr.3). Haras en 2006. Père de BERG BAHN, Brownstown St.Gr.3, BIBLE BELT, Dance Design S.Gr.3, BRENDAN BRACKAN, Solonaway St.Gr.3, BIBLE BLACK, Star Appeal St.L., BOB LE BEAU, Martin Molony St.L.,BACKBENCH BLUES, Moment of Weakness, Blaze Brightly, Banksters Bonus, 1re mère RAFINE, 7 places à 2 et 3 ans, 2e Prix du Château de Blandy-les-Tours à Fontainebleau, 4e Prix de Mogador à Longchamp. Mère de : N., (f.2012, Big Bad Bob). N., (voir ci-dessus), son troisième produit. 2e mère LA BELGA (ARG), 3 vict., GP Eliseo Ramirez (Gr.1), GP Saturnino J Unzue (Gr.1), de Potrancas (Gr.1), Carrera de las Estrellas 2yo Fillies (Gr.1), Clasico Carlos P Rodriguez (Gr.2), Sibila (Gr.2), 3e Clasico Eudoro J Balsa (Gr.3). -

The Looking-Glass World: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting 1850-1915

THE LOOKING-GLASS WORLD Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I Claire Elizabeth Yearwood Ph.D. University of York History of Art October 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite painting as a significant motif that ultimately contributes to the on-going discussion surrounding the problematic PRB label. With varying stylistic objectives that often appear contradictory, as well as the disbandment of the original Brotherhood a few short years after it formed, defining ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ as a style remains an intriguing puzzle. In spite of recurring frequently in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly in those by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the mirror has not been thoroughly investigated before. Instead, the use of the mirror is typically mentioned briefly within the larger structure of analysis and most often referred to as a quotation of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) or as a symbol of vanity without giving further thought to the connotations of the mirror as a distinguishing mark of the movement. I argue for an analysis of the mirror both within the context of iconographic exchange between the original leaders and their later associates and followers, and also that of nineteenth- century glass production. The Pre-Raphaelite use of the mirror establishes a complex iconography that effectively remytholgises an industrial object, conflates contradictory elements of past and present, spiritual and physical, and contributes to a specific artistic dialogue between the disparate strands of the movement that anchors the problematic PRB label within a context of iconographic exchange. -

Pharoah Bids to Join Big Guns Of

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2018 KEESEP: PHAROAH BIDS LADY ELI TO BE OFFERED AT KEENELAND NOVEMBER TO JOIN BIG GUNS OF Eclipse Award winner Lady Eli (Divine Park--Sacre Coeur, by Saint Ballado), a Grade I winner each year from age two to five >THE TAPIT ERA= and described by Chad Brown as Athe best turf horse I=ve ever trained,@ will be offered in foal to War Front by John Sikura=s Hill >n= Dale Farm at this year=s Keeneland Breeding Stock November Sale, it was announced Saturday. Bred in Kentucky by Catesby W. Clay and Runnymede Farm Inc., Lady Eli--also a graduate of Keeneland=s September and April 2-Year-Old sales--was perfect in three starts as a juvenile, including the 2014 GI Breeders= Cup Juvenile Fillies= Turf, and tacked on three consecutive victories as a 3-year-old, capped by a rousing success in the GI Belmont Oaks Invitational. Cont. p5 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Triple Crown winner American Pharoah pictured at THE TIN MAN GETS HIS TURN IN SPRINT CUP Ashford Stud shortly after capturing the 2015 GI Breeders= The Tin Man (GB) (Equiano {Fr}) struck for the first time this Cup Classic at Keeneland | Sherackatthetrack year when gaining a deserved win in the G1 Sprint Cup at Haydock. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. by Chris McGrath So let=s hear it for Hip 4538. A chestnut filly by Hampton Court (Aus) (Redoute=s Choice {Aus}). Not a bad page, actually: she=s out of a half-sister to the dual Grade II-winning dam of a Breeders= Cup runner-up. -

'Writing' Media: an Investigation of Practical Production in Media Education by Secondary School Students

'WRITING' MEDIA: AN INVESTIGATION OF PRACTICAL PRODUCTION IN MEDIA EDUCATION BY SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS. BY JULIAN SEFTON-GREEN Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements for the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy in Education Institute ofEducation, University ofLondon January 1998 Abstract Chapter 1 provides an historical analysis ofthe role ofpractical production in media education in England. It discusses its varied educational aims. The need to consider practical work as a form of writing is advanced. Traditional notions of media education have possessed few theories of language and learning and have failed to conceptualise a relationship between critical understanding and making media. Discussion of 'media literacy' and 'visual literacy' is followed by an exploration of models of the writing process and the limits of the metaphor ofliteracy when applied to forms of media production. Selective accounts of theories ofwriting instruction (drawing upon models of the writing process), conclude that there are problems with the metaphor of media literacy. By contrast Cultural Studies has conceptualised creative productions by young people in terms that evoke notions of the written. The central research question is formulated in Chapter 2: what sense can we make ofmedia production using theories of writing; and thus by implication what change to such theories might be made using data drawn from educational research on media production? In Chapter 3 discussion of methodological questions draws attention to two traditions: Cultural Studies work on media audiences. and classroom based action research. Different methods of textual analysis are applied to media productions by young people in the next four chapters (4-7) within the specific histories of several classrooms in North London schools.