Mountaintop-Playnotes.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Luther King Jr.'S Mission and Its Meaning for America and the World

To the Mountaintop Martin Luther King Jr.’s Mission and Its Meaning for America and the World New Revised and Expanded Edition, 2018 Stewart Burns Cover and Photo Design Deborah Lee Schneer © 2018 by Stewart Burns CreateSpace, Charleston, South Carolina ISBN-13: 978-1985794450 ISBN-10: 1985794454 All Bob Fitch photos courtesy of Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, reproduced with permission Dedication For my dear friend Dorothy F. Cotton (1930-2018), charismatic singer, courageous leader of citizenship education and nonviolent direct action For Reverend Dr. James H. Cone (1936-2018), giant of American theology, architect of Black Liberation Theology, hero and mentor To the memory of the seventeen high school students and staff slain in the Valentine Day massacre, February 2018, in Parkland, Florida, and to their families and friends. And to the memory of all other schoolchildren murdered by American social violence. Also by Stewart Burns Social Movements of the 1960s: Searching for Democracy A People’s Charter: The Pursuit of Rights in America (coauthor) Papers of Martin Luther King Jr., vol 3: Birth of a New Age (lead editor) Daybreak of Freedom: Montgomery Bus Boycott (editor) To the Mountaintop: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Mission to Save America (1955-1968) American Messiah (screenplay) Cosmic Companionship: Spirit Stories by Martin Luther King Jr. (editor) We Will Stand Here Till We Die Contents Moving Forward 9 Book I: Mighty Stream (1955-1959) 15 Book II: Middle Passage (1960-1966) 174 Photo Gallery: MLK and SCLC 1966-1968 376 Book III: Crossing to Jerusalem (1967-1968) 391 Afterword 559 Notes 565 Index 618 Acknowledgments 639 About the Author 642 Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the preeminent Jewish theologian, introduced Martin Luther King Jr. -

Performance Measurement Report

THEATER SUBDISTRICT COUNCIL, LDC Performance Measurement Report I. How efficiently or effectively has TSC been in making grants which serve to enhance the long- term viability of Broadway through the production of plays and small musicals? The TSC awards grants, among other purposes, to facilitate the production of plays and musicals. The current round, awarding over $2.16 million in grants for programs, which have or are expected to result in the production of plays or musicals, have been awarded to the following organizations: • Classical Theatre of Harlem $100,000 (2009) Evaluation: A TSC grant enabled the Classical Theatre of Harlem to produce Archbishop Supreme Tartuffe at the Harold Clurman Theatre on Theatre Row in Summer 2009. This critically acclaimed reworking of Moliere’s Tartuffe directed by Alfred Preisser and featuring Andre DeShields was an audience success. The play was part of the theater’s Project Classics initiative, designed to bring theater to an underserved and under-represented segment of the community. Marketing efforts successfully targeted audiences from north of 116th Street through deep discounts and other ticket offers. • Fractured Atlas $200,000 (2010) Evaluation: Fractured Atlas used TSC support for a three-part program to improve the efficiency of rehearsal and performance space options, gather useful workspace data, and increase the availability of affordable workspace for performing arts groups in the five boroughs. Software designers created a space reservation calendar and rental engine; software for an enhanced data-reporting template was written, and strategies to increase the use of nontraditional spaces for rehearsal and performance were developed. • Lark Play Development Center $160,000 (2010) Evaluation: Lark selected four New York playwrights from diverse backgrounds to participate in a new fellowship program: Joshua Allen, Thomas Bradshaw, Bekah Brunstetter, and Andrea Thome. -

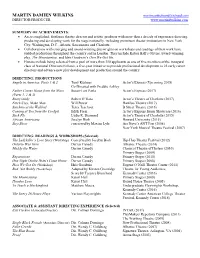

Resume to Upload to Resume Page

MARTIN DAMIEN WILKINS [email protected] DIRECTOR/PRODUCER www.martindwilkins.com SUMMARY OF ACHIEVEMENTS: • An accomplished, freelance theater director and artistic producer with more than a decade of experience directing, producing and developing work for the stage nationally, including prominent theater institutions in New York City, Washington, D.C., Atlanta, Sacramento and Charlotte. • Collaborations with emerging and award-winning playwrights on workshops and readings of their work have yielded productions throughout the country and in London. They include Katori Hall’s Olivier Award-winning play, The Mountaintop, and Idris Goodwin’s How We Got On. • Honors include being selected from a pool of more than 350 applicants as one of five members of the inaugural class of National Directors Fellows, a five-year initiative to provide professional development to 25 early career directors and advance new play development and production around the country. DIRECTING: PRODUCTIONS Angels in America: Parts 1 & 2 Tony Kushner Actor’s Express (Upcoming 2018) Co-Directed with Freddie Ashley Father Comes Home from the Wars Suzan-Lori Parks Actor’s Express (2017) (Parts 1, 2 & 3) Bootycandy Robert O’Hara Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte (2017) Fetch Clay, Make Man Will Power Hattiloo Theatre (2017) Satchmo at the Waldorf Terry Teachout B Street Theatre (2016) Coming at You from the Cockpit Edith Freni Actor’s Express Intern Showcase (2016) Stick Fly Lydia R. Diamond Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte (2015) African Americans Jocelyn Bioh Howard University -

MLK Resource Sheet

Created by Tonysha Taylor and Leah Grannum MLAC DEI 2021 Below you will find a complied list of resources, articles, events and more to honor the life and legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. The attempted coup at the Capitol on January 6th, 2021 was another reminder that we still have a lot of work to do to dismantle white supremacy. We hope you take this time to reflect, learn and remember Martin Luther King Jr. and his legacy- what he died for and what we continue to fight for. Resources and Virtual Events Teaching Black History and Culture: An Online Workshop for Educators. The workshop will be virtual (via Zoom) and combine a webinar, video and live streaming. Hosted by the Thomas D. Clark Foundation. Presented live from the Muhammad Ali Center. For more info and registration: https://nku.eventsair.com/ shcce/teaching/Site/Register Martin Luther King Jr. Day is a United States, holiday (third Monday in January) honoring the achievements of Martin Luther King, Jr. King’s birthday was finally approved as a federal holiday in 1983, and all 50 states A Call to Action: Then and Now: Dr. Martin Luther King, made it a state government holiday by 2000. Officially, King Jr. Celebration was born on January 15, 1929 in Atlanta. But the King holiday is marked every year on the third Monday in January. On January 18, 2021 at 3:45 p.m. EST the Madam Walker Legacy Center and Indiana University will Muhammad Ali Center MLK Day Celebration present "A Call to Action: Then and Now," a social justice virtual program with two of this nation's most prolific civil rights activists. -

The Dreamer: Remembering Dr. King by Quincy D

The Dreamer: Remembering Dr. King By Quincy D. Brown – January 15, 2018 There is little difference between an idealistic dreamer and visionary activist when both decide to act on their inspiration. Joseph, one the Bible's most noteworthy dreamers, told his brothers two of his dreams. The first of Joseph’s dream was about sheaves of wheat bowing down to him. And if this wasn’t enough, he told his second dream to his father about the Sun and Moon and eleven stars bowing down to him. The implication of both dreams was that Joseph surmised that his eleven brothers (represented by the sheaves and eleven stars) and his father and mother (represented by the Sun and Moon) would one day bow down to his authority. Naturally, Joseph’s father tried to correct his son's youthful naiveté. His brothers, however, were not as patient or versed in the delicate art of persuasion. Instead, they resented him and tried to beat “the stuff of his dreams” out of him. The thinking goes: What do you do about a younger sister who has gotten out of line? What do you do about a little brother who dares to believe that he is equal to the eldest? What happens when a sibling begins to dream the impossible and their family doesn’t approve of it? Had not an assassin's bullet snuffed out his life prematurely, another noteworthy dreamer and visionary activist would have celebrated his 89th birthday this year. Like Joseph, Dr. King was a dreamer. He saw what others could not see. -

Senator Robert F. Kennedy Speaks on Martin Luther King Jr. Jfk.Org/Teach

LESSON PLAN Senator Robert F. Kennedy Speaks on Martin Luther King Jr. Analyzing Speeches Given on April 4 and 5, 1968 after the Death of Dr. King Courtesy Indianapolis Star jfk.org/teach Educational programs are offered at the Museum, at your school or via distance learning. For more information, email [email protected] | Book a school visit at jfk.org/schoolvisits LESSON PLAN Senator Robert F. Kennedy Speaks on Martin Luther King Jr.: Analyzing Speeches Given on April 4 and 5, 1968 after the Death of Dr. King Historic Context: On April 3, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke in Memphis to a capacity crowd at the Mason Temple Church. He gave his final speech, the now-famous “Mountaintop” speech, in which he tells the audience, preparing to participate in protests that were to begin the next day, that “he may not get there with them.” Some feel it was foreshadowing his death – on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee at the Lorraine Motel. Senator Robert F. Kennedy was campaigning in Indiana for the Democratic Nomination for President of the United States at that time, and he gave two speeches within 24 hours in response to Dr. King’s assassination: one was spontaneous and unscripted, and the other was prepared and scripted. Essential Questions: How do the speeches given on April 4 and 5, 1968 by Senator Robert F. Kennedy differ in impact, structure and persuasive technique? Which one would most inspire you to act? What action could you have taken in 1968? What actions can you take today? Learning Objectives: The student will be able to: • Identify and summarize the main points of each speech given by Senator Robert F. -

At Play 2017 FINAL.Indd

ISSUE 18 SPRING www.dramatists.com 2017 From Clifford Odets to Tennessee Williams to Stephen Karam, Lillian Hellman to Paula Vogel to Katori Hall, Kaufman & Hart and Edna Ferber to Wendy Wasserstein to Annie Baker and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, DPS has been the proud first publisher of plays by writers who went on to define, and redefine, the American theater. ounded as essentially a cooperative Though their subjects range from slaughterhouse Fbetween the Dramatists Guild and playwriting employees to the titans of global finance to families agents, the Play Service's commitment to nurturing in the not-so-distant future, each of these plays new talent is foregrounded in the company's challenges readers and audiences to consider mission. While we are ever proud to represent what theater, that most humanist of mediums, can plays honored by Tony Awards® (including all four be. And, in an embarrassment of riches, the 15 of the 2017 Best Play Tony nominees) and Pulitzer writers featured herein are only a fraction of the Prizes, we are equally proud to count among our individuals whose first plays or early-stage career writers every year the fresh faces whose work efforts DPS publishes. may not yet be nationally known but whose talent n the back of this newsletter you'll find an is immense. The plays highlighted by these 15 Ooverview of new partnerships between emerging writers published in 2016-2017 are DPS and play development organizations, who do astonishing, invigorating explorations of identity, the critical daily work of providing resources for history, consciousness, politics, and language. -

The Contemporary Rhetoric About Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X in the Post-Reagan Era

ABSTRACT THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA by Cedric Dewayne Burrows This thesis explores the rhetoric about Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X in the late 1980s and early 1990s, specifically looking at how King is transformed into a messiah figure while Malcolm X is transformed into a figure suitable for the hip-hop generation. Among the works included in this analysis are the young adult biographies Martin Luther King: Civil Rights Leader and Malcolm X: Militant Black Leader, Episode 4 of Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads, and Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X. THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Cedric Dewayne Burrows Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2005 Advisor_____________________ Morris Young Reader_____________________ Cynthia Leweicki-Wison Reader_____________________ Cheryl L. Johnson © Cedric D. Burrows 2005 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One A Dead Man’s Dream: Martin Luther King’s Representation as a 10 Messiah and Prophet Figure in the Black American’s of Achievement Series and Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads Chapter Two Do the Right Thing by Any Means Necessary: The Revival of Malcolm X 24 in the Reagan-Bush Era Conclusion 39 iii THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA Introduction “What was Martin Luther King known for?” asked Mrs. -

History of Arena Stage: Where American Theater Lives the Mead Center for American Theater

History oF arena Stage: Where American Theater Lives The Mead Center for American Theater Arena Stage was founded August 16, 1950 in Washington, D.C. by Zelda Fichandler, Tom Fichandler and Edward Mangum. Over 65 years later, Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater, under the leadership of Artistic Director Molly Smith and Executive Director Edgar Dobie, is a national center dedicated to American voices and artists. Arena Stage produces plays of all that is passionate, profound, deep and dangerous in the American spirit, and presents diverse and ground- breaking work from some of the best artists around the country. Arena Stage is committed to commissioning and developing new plays and impacts the lives of over 10,000 students annually through its work in community engagement. Now in its seventh decade, Arena Stage serves a diverse annual audience of more than 300,000. When Zelda and Tom Fichandler and a handful of friends started Arena Stage, there was no regional theater movement in the United States or resources to support a theater committed to providing quality work for its community. It took time for the idea of regional theater to take root, but the Fichandlers, together with the people of the nation’s capital, worked patiently to build the fledgling theater into a diverse, multifaceted, internationally renowned institution. Likewise, there were no professional theaters operating in Washington, D.C. in 1950. Actors’ Equity rules did not permit its members to perform in segregated houses, and neither The National nor Ford’s Theatre was integrated. From its inception, Arena opened its doors to anyone who wished to buy a ticket, becoming the first integrated theater in this city. -

Martin Luther King Jr January 2021

Connections Martin Luther King Jr January 2021 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PMB Administrative Services and the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights Message from the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Administrative Services January 2021 Dear Colleagues, The life and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., inspires me every day, particularly when the troubles of the world seem to have placed what appear to be insurmountable obstacles on the path to achieving Dr. King’s vision. Yet I know that those obstacles will eventually melt away when we focus our hearts and minds on finding solutions together. While serving as leaders of the civil rights movement, Dr. and Mrs. King raised their family in much the same way my dear parents raised my brothers and myself. It gives me comfort to know that at the end of the day, their family came together in love and faith the same way our family did, grateful for each other and grateful knowing the path ahead was illuminated by a shared dream of a fair and equitable world. This issue of Connections begins on the next page with wise words of introduction from our collaborative partner, Erica White-Dunston, Director of the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights. Erica speaks eloquently of Dr. King’s championing of equity, diversity and inclusion in all aspects of life long before others understood how critically important those concepts were in creating and sustaining positive outcomes. I hope you find as much inspiration and hope within the pages of this month’s Connections magazine as I did. -

<I>Twenty-First Century American Playwrights</I>

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadt.commons.gc.cuny.edu Twenty-First Century American Playwrights Twenty-First Century American Playwrights. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018; Pp. 228. In 1982, Christopher Bigsby penned A Critical Introduction to Twentieth-Century American Drama. What was originally planned as a single volume expanded to three, with volume 2 being released in 1984 and Volume 3 in 1985. Although Bigsby, a literary analyst and novelist with more than 50 books to his credit, hails from Britain, he is drawn to American playwrights because of their “stylistic inventiveness…sexual directness…[and] characters ranged across the social spectrum in a way that for long, and for the most part, had not been true of the English theatre” (1). This admiration brought Bigsby’s research across the millennium line to give us his latest offering Twenty-First Century American Playwrights. What Bigsby provides is an in-depth survey of nine writers who entered the American theatre landscape during the past twenty years, including chapters on Annie Baker, Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig, Katori Hall, Amy Herzog, Tracy Letts, David Lindsay-Abaire, Lynn Nottage, Sarah Ruhl, and Naomi Wallace. While these playwrights vary in the manner they work and styles of creative output, what places them together in this volume “is the sense that theatre has a unique ability to engage with audiences in search of some insight into the way we live…to witness how words become manifest, how artifice can, at its best, be the midwife of truth” (5). This explanation, however vague, does little to provide a concrete rubric for why these dramatists were included over others. -

The Women's Voices Theater Festival

STUDY GUIDE In the fall of 2015, more than 50 professional theaters in Washington, D.C. are each producing at least one world premiere play by a female playwright. The Women’s Voices Theater Festival is history’s largest collaboration of theater companies working simultaneously to produce original works by female writers. CONSIDER WHY A WOMEN’S VOICES THEATER FESTIVAL? • Why is it important If someone asked you to quickly name three playwrights, who would they be? for artists of diverse backgrounds to have Shakespeare likely tops your list. Perhaps you remember Arthur Miller, Tennessee their work seen by Williams or August Wilson. Sophocles, Molière, Marlowe, Ibsen, Chekov, Shaw, O’Neill — these are among the most famous Western playwrights. They are central audiences? to the dramatic canon. A “canon” is an authoritative list of important works — think of it as the official “Top 40” of dramatic literature. Their plays are the most likely • What is the impact of to be seen onstage and assigned in schools. seeing a play that you can connect to your own A large group is often missing from the canon, professional stages, traditional experience? reading lists and your education in theater: women playwrights. Plays by women are as important, artistic, rigorous, compelling and producible as • How would you react plays by men. They are also plentiful. Women’s perspectives are also key to more if you knew that you fully understanding our world. and the playwright of According to a recent Washington Post article, surveys say that D.C. audiences a production you were are 61 percent female and Broadway audiences are 68 percent female.