Linear Structural Elements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tectonic Imbrication and Foredeep Development in the Penokean

Tectonic Imbrication and Foredeep Development in the Penokean Orogen, East-Central Minnesota An Interpretation Based on Regional Geophysics and the Results of Test-Drilling The Penokean Orogeny in Minnesota and Upper Michigan A Comparison of Structural Geology U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1904-C, D AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general in Books of the U.S. -

Significance of Brittle Deformation in the Footwall

Journal of Structural Geology 64 (2014) 79e98 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsg Significance of brittle deformation in the footwall of the Alpine Fault, New Zealand: Smithy Creek Fault zone J.-E. Lund Snee a,*,1, V.G. Toy a, K. Gessner b a Geology Department, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand b Western Australian Geothermal Centre of Excellence, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia article info abstract Article history: The Smithy Creek Fault represents a rare exposure of a brittle fault zone within Australian Plate rocks that Received 28 January 2013 constitute the footwall of the Alpine Fault zone in Westland, New Zealand. Outcrop mapping and Received in revised form paleostress analysis of the Smithy Creek Fault were conducted to characterize deformation and miner- 22 May 2013 alization in the footwall of the nearby Alpine Fault, and the timing of these processes relative to the Accepted 4 June 2013 modern tectonic regime. While unfavorably oriented, the dextral oblique Smithy Creek thrust has Available online 18 June 2013 kinematics compatible with slip in the current stress regime and offsets a basement unconformity beneath Holocene glaciofluvial sediments. A greater than 100 m wide damage zone and more than 8 m Keywords: Fault zone wide, extensively fractured fault core are consistent with total displacement on the kilometer scale. e Fluid flow Based on our observations we propose that an asymmetric damage zone containing quartz carbonate Hydrofracture echloriteeepidote veins is focused in the footwall. -

FIELD TRIP: Contractional Linkage Zones and Curved Faults, Garden of the Gods, with Illite Geochronology Exposé

FIELD TRIP: Contractional linkage zones and curved faults, Garden of the Gods, with illite geochronology exposé Presenters: Christine Siddoway and Elisa Fitz Díaz. With contributions from Steven A.F. Smith, R.E. Holdsworth, and Hannah Karlsson This trip examines the structural geology and fault geochronology of Garden of the Gods, Colorado. An enclave of ‘red rock’ terrain that is noted for the sculptural forms upon steeply dipping sandstones (against the backdrop of Pikes Peak), this site of structural complexity lies at the south end of the Rampart Range fault (RRF) in the southern Colorado Front Range. It features Laramide backthrusts, bedding plane faults, and curved fault linkages within subvertical Mesozoic strata in the footwall of the RRF. Special subjects deserving of attention on this SGTF field trip are deformation band arrays and younger-upon-older, top-to-the-west reverse faults—that well may defy all comprehension! The timing of RRF deformation and formation of the Colorado Front Range have long been understood only in general terms, with reference to biostratigraphic controls within Laramide orogenic sedimentary rocks, that derive from the Laramide Front Range. Using 40Ar/39Ar illite age analysis of shear-generated illite, we are working to determine the precise timing of fault movement in the Garden of the Gods and surrounding region provide evidence for the time of formation of the Front Range monocline, to be compared against stratigraphic-biostratigraphic records from the Denver Basin. The field trip will complement an illite geochronology workshop being presented by Elisa Fitz Díaz on 19 June. If time allows, and there is participant interest, we will make a final stop to examine fault-bounded, massive sandstone- and granite-hosted clastic dikes that are associated with the Ute Pass fault. -

Evolution of a Highly Dilatant Fault Zone in the Grabens of Canyonlands

Solid Earth, 6, 839–855, 2015 www.solid-earth.net/6/839/2015/ doi:10.5194/se-6-839-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Evolution of a highly dilatant fault zone in the grabens of Canyonlands National Park, Utah, USA – integrating fieldwork, ground-penetrating radar and airborne imagery analysis M. Kettermann1, C. Grützner2,a, H. W. van Gent1,b, J. L. Urai1, K. Reicherter2, and J. Mertens1,c 1Structural Geology, Tectonics and Geomechanics Energy and Mineral Resources Group, RWTH Aachen University, Lochnerstraße 4–20, 52056 Aachen, Germany 2Neotectonics and Natural Hazards, RWTH Aachen University, Lochnerstraße 4–20, 52056 Aachen, Germany anow at: COMET; Bullard Laboratories, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK bnow at: Shell Global Solutions International, Rijswijk, the Netherlands cnow at: ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland Correspondence to: M. Kettermann ([email protected]) Received: 20 February 2015 – Published in Solid Earth Discuss.: 17 March 2015 Revised: 18 June 2015 – Accepted: 22 June 2015 – Published: 21 July 2015 Abstract. The grabens of Canyonlands National Park are 1 Introduction a young and active system of sub-parallel, arcuate grabens, whose evolution is the result of salt movement in the sub- Understanding the structure of dilatant fractures in normal surface and a slight regional tilt of the faulted strata. We fault zones is important for many applications in geoscience. present results of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys Reservoirs for hydrocarbons, geothermal energy and fresh- in combination with field observations and analysis of high- water often contain dilatant fractures (e.g., Ehrenberg and resolution airborne imagery. -

Multiphase Boudinage: a Case Study of Amphibolites in Marble in the Naxos Migmatite Core

Solid Earth, 9, 91–113, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/se-9-91-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Multiphase boudinage: a case study of amphibolites in marble in the Naxos migmatite core Simon Virgo, Christoph von Hagke, and Janos L. Urai Structural Geology, Tectonics and Geomechanics, RWTH Aachen University, Lochnerstrasse 4–20, 52056 Aachen, Germany Correspondence: Simon Virgo ([email protected]) Received: 15 August 2017 – Discussion started: 23 August 2017 Revised: 18 December 2017 – Accepted: 20 December 2017 – Published: 15 February 2018 Abstract. In multiply deformed terrains multiphase boudi- sions, it has been shown that in three dimensions boudins can nage is common, but identification and analysis of these is be complex (Abe et al., 2013; Marques et al., 2012; Zulauf et difficult. Here we present an analysis of multiphase boudi- al., 2011b). This complexity can be distinctive when boudins nage and fold structures in deformed amphibolite layers in are the result of more than one deformation event. Some mul- marble from the migmatitic centre of the Naxos metamor- tiphase structures such as mullions or bone boudins are in- phic core complex. Overprinting between multiple boudi- dicative of a specific sequence of deformation (Kenis et al., nage generations is shown in exceptional 3-D outcrop. We 2005; Maeder et al., 2009). Chocolate tablet boudins form identify five generations of boudinage, reflecting the transi- by two phases of extension of layers in different directions tion from high-strain high-temperature ductile deformation (Abe and Urai, 2012; Ghosh, 1988; Zulauf et al., 2011a, to medium- to low-strain brittle boudins formed during cool- b), and have been used to analyse the deformation history ing and exhumation. -

Lithology and Internal Structure of the San Andreas Fault at Depth Based

1 1 Lithology and Internal Structure of the San Andreas Fault at depth based on 2 characterization of Phase 3 whole-rock core in the San Andreas Fault Observatory at 3 Depth (SAFOD) Borehole 4 By Kelly K. Bradbury1, James P. Evans1, Judith S. Chester2, Frederick M. Chester2, and David L. Kirschner3 5 1Geology Department, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84321-4505 6 2Center for Tectonophysics and Department of Geology and Geophysics, Texas A&M University, College Station, 7 Texas 77843 8 3Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, St. Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri 63108 9 10 Abstract 11 We characterize the lithology and structure of the spot core obtained in 2007 during 12 Phase 3 drilling of the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth (SAFOD) in order to determine 13 the composition, structure, and deformation processes of the fault zone at 3 km depth where 14 creep and microseismicity occur. A total of approximately 41 m of spot core was taken from 15 three separate sections of the borehole; the core samples consist of fractured arkosic sandstones 16 and shale west of the SAF zone (Pacific Plate) and sheared fine-grained sedimentary rocks, 17 ultrafine black fault-related rocks, and phyllosilicate-rich fault gouge within the fault zone 18 (North American Plate). The fault zone at SAFOD consists of a broad zone of variably damaged 19 rock containing localized zones of highly concentrated shear that often juxtapose distinct 20 protoliths. Two zones of serpentinite-bearing clay gouge, each meters-thick, occur at the two 21 locations of aseismic creep identified in the borehole on the basis of casing deformation. -

Faults and Joints

133 JOINTS Joints (also termed extensional fractures) are planes of separation on which no or undetectable shear displacement has taken place. The two walls of the resulting tiny opening typically remain in tight (matching) contact. Joints may result from regional tectonics (i.e. the compressive stresses in front of a mountain belt), folding (due to curvature of bedding), faulting, or internal stress release during uplift or cooling. They often form under high fluid pressure (i.e. low effective stress), perpendicular to the smallest principal stress. The aperture of a joint is the space between its two walls measured perpendicularly to the mean plane. Apertures can be open (resulting in permeability enhancement) or occluded by mineral cement (resulting in permeability reduction). A joint with a large aperture (> few mm) is a fissure. The mechanical layer thickness of the deforming rock controls joint growth. If present in sufficient number, open joints may provide adequate porosity and permeability such that an otherwise impermeable rock may become a productive fractured reservoir. In quarrying, the largest block size depends on joint frequency; abundant fractures are desirable for quarrying crushed rock and gravel. Joint sets and systems Joints are ubiquitous features of rock exposures and often form families of straight to curviplanar fractures typically perpendicular to the layer boundaries in sedimentary rocks. A set is a group of joints with similar orientation and morphology. Several sets usually occur at the same place with no apparent interaction, giving exposures a blocky or fragmented appearance. Two or more sets of joints present together in an exposure compose a joint system. -

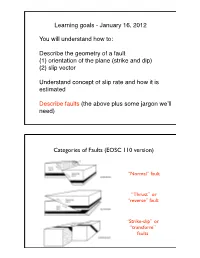

Describe the Geometry of a Fault (1) Orientation of the Plane (Strike and Dip) (2) Slip Vector

Learning goals - January 16, 2012 You will understand how to: Describe the geometry of a fault (1) orientation of the plane (strike and dip) (2) slip vector Understand concept of slip rate and how it is estimated Describe faults (the above plus some jargon weʼll need) Categories of Faults (EOSC 110 version) “Normal” fault “Thrust” or “reverse” fault “Strike-slip” or “transform” faults Two kinds of strike-slip faults Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) Stand with your feet on either side of the fault. Which side comes toward you when the fault slips? Another way to tell: stand on one side of the fault looking toward it. Which way does the block on the other side move? Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) 1992 M 7.4 Landers, California Earthquake rupture (SCEC) Describing the fault geometry: fault plane orientation How do you usually describe a plane (with lines)? In geology, we choose these two lines to be: • strike • dip strike dip • strike is the azimuth of the line where the fault plane intersects the horizontal plane. Measured clockwise from N. • dip is the angle with respect to the horizontal of the line of steepest descent (perpendic. to strike) (a ball would roll down it). strike “60°” dip “30° (to the SE)” Profile view, as often shown on block diagrams strike 30° “hanging wall” “footwall” 0° N Map view Profile view 90° W E 270° S 180° Strike? Dip? 45° 45° Map view Profile view Strike? Dip? 0° 135° Indicating direction of slip quantitatively: the slip vector footwall • let’s define the slip direction (vector) -

Geology of the Kranzberg Syncline and Emplacement Controls of the Usakos Pegmatite Field, Damara Belt, Central Namibia

GEOLOGY OF THE KRANZBERG SYNCLINE AND EMPLACEMENT CONTROLS OF THE USAKOS PEGMATITE FIELD, DAMARA BELT, CENTRAL NAMIBIA by Geoffrey J. Owen Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Prof. Alex Kisters Faculty of Science Department of Earth Sciences March 2011 i DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitely otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature: Date: 15. February 2011 ii ABSTRACT The Central Zone (CZ) of the Damara belt in central Namibia is underlain by voluminous Pan-African granites and is host to numerous pegmatite occurrences, some of which have economic importance and have been mined extensively. This study discusses the occurrence, geometry, relative timing and emplacement mechanisms for the Usakos pegmatite field, located between the towns of Karibib and Usakos and within the core of the regional-scale Kranzberg syncline. Lithological mapping of the Kuiseb Formation in the core of the Kranzberg syncline identified four litho-units that form an up to 800 m thick succession of metaturbidites describing an overall coarsening upward trend. This coarsening upwards trend suggests sedimentation of the formation’s upper parts may have occurred during crustal convergence and basin closure between the Kalahari and Congo Cratons, rather than during continued spreading as previously thought. -

Sedimentary Stylolite Networks and Connectivity in Limestone

Sedimentary stylolite networks and connectivity in Limestone: Large-scale field observations and implications for structure evolution Leehee Laronne Ben-Itzhak, Einat Aharonov, Ziv Karcz, Maor Kaduri, Renaud Toussaint To cite this version: Leehee Laronne Ben-Itzhak, Einat Aharonov, Ziv Karcz, Maor Kaduri, Renaud Toussaint. Sed- imentary stylolite networks and connectivity in Limestone: Large-scale field observations and implications for structure evolution. Journal of Structural Geology, Elsevier, 2014, pp.online first. <10.1016/j.jsg.2014.02.010>. <hal-00961075v2> HAL Id: hal-00961075 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00961075v2 Submitted on 19 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. 1 2 Sedimentary stylolite networks and connectivity in 3 Limestone: Large-scale field observations and 4 implications for structure evolution 5 6 Laronne Ben-Itzhak L.1, Aharonov E.1, Karcz Z.2,*, 7 Kaduri M.1,** and Toussaint R.3,4 8 9 1 Institute of Earth Sciences, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 91904, Israel 10 2 ExxonMobil Upstream Research Company, Houston TX, 77027, U.S.A 11 3 Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg, University of Strasbourg/EOST, CNRS, 5 rue 12 Descartes, F-67084 Strasbourg Cedex, France. -

Chapter 8 Large Strains

Chapter 8 Large Strains Introduction Most geological deformation, whether distorted fossils or fold and thrust belt shortening, accrues over a long period of time and can no longer be analyzed with the assumptions of infinitesimal strain. Fortunately, these large, or finite strains have the same starting point that infinitesimal strain does: the deformation and dis- placement gradient tensors. However, we must clearly distinguish between gradi- ents in position or displacement with respect to the initial (material) or to the final (spatial) state and several assumptions from the last Chapter — small angles, addi- tion of successive phases or steps in the deformation — no longer hold. Finite strain can get complicated very quickly with many different tensors to worry about. Most of our emphasis here will be on the practical measurement of finite strain rather than the details of the theory but we do have to review a few basic concepts first, so that we can appreciate the differences between finite and infinitesimal strain. Some of these differences have a profound impact on how we analyze de- formation. CHAPTER 8 FINITE STRAIN Comparison to Infinitesimal Strain A Plethora of Finite Strain Tensors There are lots of finite strain tensors and they come in pairs: one referenced to the initial state and the other referenced to the final state. The derivation of these tensors is usually based on Figure 7.3 and is tedious but straightforward; we will skip the derivation here but you can see it in Allmendinger et al. (2012) or any good continuum mechanics text. The first tensor is the Lagrangian strain tensor: 1 ⎡ ∂ui ∂u j ∂uk ∂uk ⎤ 1 " Lij = ⎢ + + ⎥ = ⎣⎡Eij + E ji + EkiEkj ⎦⎤ (8.1) 2 ⎣∂ X j ∂ Xi ∂ Xi ∂ X j ⎦ 2 where Eij is the displacement gradient tensor from the last Chapter. -

Composition, Alteration, and Texture of Fault-Related Rocks from Safod Core and Surface Outcrop Analogs

Pure Appl. Geophys. Ó 2014 Springer Basel DOI 10.1007/s00024-014-0896-6 Pure and Applied Geophysics Composition, Alteration, and Texture of Fault-Related Rocks from Safod Core and Surface Outcrop Analogs: Evidence for Deformation Processes and Fluid-Rock Interactions 1 1 1 1 1 KELLY K. BRADBURY, COLTER R. DAVIS, JOHN W. SHERVAIS, SUSANNE U. JANECKE, and JAMES P. EVANS Abstract—We examine the fine-scale variations in mineralogi- 1. Introduction cal composition, geochemical alteration, and texture of the fault- related rocks from the Phase 3 whole-rock core sampled between 3,187.4 and 3,301.4 m measured depth within the San Andreas Fault Well-constrained geological, geochemical, and Observatory at Depth (SAFOD) borehole near Parkfield, California. geophysical models of active fault zones are needed if This work provides insight into the physical and chemical properties, we are to understand fault zone behavior and earth- structural architecture, and fluid-rock interactions associated with the actively deforming traces of the San Andreas Fault zone at depth. quake deformation, constraining the factors that affect Exhumed outcrops within the SAF system comprised of serpentinite- the distribution of earthquakes, and the nature of slip bearing protolith are examined for comparison at San Simeon, Goat in the shallow crust by developing realistic models of Rock State Park, and Nelson Creek, California. In the Phase 3 SAFOD drillcore samples, the fault-related rocks consist of multiple subsurface fault zone structure and ground motion juxtaposed lenses of sheared, foliated siltstone and shale with block- predictions. Earthquakes nucleate in rocks at depth in-matrix fabric, black cataclasite to ultracataclasite, and sheared (e.g., FAGERENG and TOY 2011;SIBSON 1977; 2003), serpentinite-bearing, finely foliated fault gouge.