ABSTRACT BURNETTE, SAMARA FLEMING. Resiliency in Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hobbs Moore Was Born on May 23, Focused on a Theoretical Analysis of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey

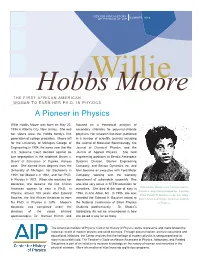

CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS AT AIP SUMMER 2014 Willie Hobbs Moore THE FIRST AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMAN TO EARN HER PH.D. IN PHYSICS A Pioneer in Physics Willie Hobbs Moore was born on May 23, focused on a theoretical analysis of 1934 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. She and secondary chlorides for polyvinyl-chloride her sisters were the Hobbs family’s first polymers. Her research has been published generation of college graduates. Moore left in a number of scientific journals including for the University of Michigan College of the Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy, the Engineering in 1954, the same year that the Journal of Chemical Physics, and the U.S. Supreme Court decided against de Journal of Applied Physics. She held jure segregation in the landmark Brown v. engineering positions at Bendix Aerospace Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas Systems Division, Barnes Engineering case. She earned three degrees from the Company, and Sensor Dynamics Inc. and University of Michigan: her Bachelor’s in later became an executive with Ford Motor 1958, her Master’s in 1961, and her Ph.D. Company, working with the warranty in Physics in 1972. When she received her department of automobile assembly. She doctorate, she became the first African was also very active in STEM education for American woman to earn a Ph.D. in minorities. She died at the age of sixty in Willie Hobbs Moore circa 1958 pictured in Women in Engineering Magazine. Courtesy Physics, almost 100 years after Edward 1994, in Ann Arbor, MI. In 1995, she was of the Ronald E. -

JASMINE JONES, Phd Email: [email protected] | Web

JASMINE JONES, PhD Email: [email protected] | Web: http://seejazzwork.com SUMMARY My research addresses the sociotechnical challenges of making embedded computing socially acceptable in everyday life. My methodology includes ethnographic methods, development of novel IoT technologies, field studies, and artistic explorations. Domains: collective memory, health and wellness, assistive devices EDUCATION PhD in Information Science, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor § Advisor: Dr. Mark S. Ackerman § Thesis: “Crafting a Narrative Inheritance: A Design Framework for Intergenerational Family Memory” B.S. Computer Science, University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) B.A. Interdisciplinary Studies: “Human-Computer Interaction in an International Cultural Context”, University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) § Magna cum laude Visiting Scholar, Creative Interaction Design Lab, KAIST, South Korea Visiting Student, Human-Computer Interaction, University of Melbourne, Australia HONORS, FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Academic Fellowships 2019-20 BlackComputeHer Leadership Fellow 2018 Postdoctoral Fellow, Big10 Academic Alliance Professorial Advancement Initiative (PAI) 2016 NSF/Korea National Research Foundation GROW International Research Fellow 2016 Engaged Pedagogy Fellow, Center for Community-Engaged Academic Learning (Michigan) 2013-16 NSF Graduate Research Fellowship 2012-17 GEM Fellowship 2012-17 University of Michigan Rackham Merit Fellow 2012 Google Anita Borg Scholar - Finalist 2007-12 Meyerhoff Scholar (UMBC) 2007-12 CWIT Scholar (UMBC Center -

Human Centered Computing New Degree

HCC PhD New Degree Proposal April, 17 2015 GC1 Board of Governors, State University System of Florida Request to Offer a New Degree Program (Please do not revise this proposal format without prior approval from Board staff) University of Florida Fall 2016 University Submitting Proposal Proposed Implementation Term CISE College of Engineering Name of College(s) or School(s) Name of Department(s)/ Division(s) Doctor of Philosophy Human-Centered Computing Academic Specialty or Field Complete Name of Degree 11.0104 Proposed CIP Code The submission of this proposal constitutes a commitment by the university that, if the proposal is approved, the necessary financial resources and the criteria for establishing new programs have been met prior to the initiation of the program. Date Approved by the University Board of President Date Trustees Signature of Chair, Board of Date Vice President for Academic Date Trustees Affairs Provide headcount (HC) and full-time equivalent (FTE) student estimates of majors for Years 1 through 5. HC and FTE estimates should be identical to those in Table 1 in Appendix A. Indicate the program costs for the first and the fifth years of implementation as shown in the appropriate columns in Table 2 in Appendix A. Calculate an Educational and General (E&G) cost per FTE for Years 1 and 5 (Total E&G divided by FTE). Projected Implementatio Projected Program Costs Enrollment n Timeframe (From Table 2) (From Table 1) E&G Contract E&G Auxiliary Total HC FTE Cost per & Grants Funds Funds Cost FTE Funds Year 1 12 8.4 55,740 468,215 0 0 468,215 Year 2 20 14 Year 3 30 21 Year 4 40 28 Year 5 50 35 15,057 526,981 0 0 526,981 Note: This outline and the questions pertaining to each section must be reproduced within the body of the proposal to ensure that all sections have been satisfactorily addressed. -

This Dissertation, Titled

This dissertation, titled “’We Must Keep Reaching Across the Table and Feed Each Other‘: Life Stories of Black Women in Academic Leadership Roles in Higher Education at Predominantly White Institutions,” has been modified from the form in which it was originally published. Specifically, certain sections have been revised to ensure that the text represents original work. DATE: July 2, 2018 “WE MUST KEEP REACHING ACROSS THE TABLE AND FEED EACH OTHER” LIFE STORIES OF BLACK WOMEN IN ACADEMIC LEADERSHIP ROLES IN HIGHER EDUCATION AT PREDOMINANTLY WHITE INSTITUTIONS BY DESIRÉE YVETTE MCMILLION DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Policy, Organization and Leadership with a concentration in African-American Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Yoon K. Pak, Chair Professor James D. Anderson Assistant Professor Shardé N. Smith Associate Professor Christopher M. Span Abstract “Black women have obtained leadership position as administrators at higher education institutions. While previous research has demonstrated that obtaining leadership positions is problematic for Black women, little research focuses solely on the plight and personal agency of Black women administrators”.1 While there exists a substantial body of literature devoted to examining the ways in which sexism, Anti-Black racism, gender and class inequality shape and limit leadership opportunities for Black women in education, few studies have focused on the personal agency of these women and how it influences their actions with regard to leadership within higher education. This phenomenological study examines the lived experiences of Black women in administrative leadership roles in higher education at predominantly white institutions and how race and gender intersect, and contribute to their career trajectories in academia. -

Quality & Quantity: Participation of Women and Minorities in Physics

TM CSWP Vol. 29, No. 1 Spring 2010 The Newsletter of the Committee on the Status of Women in Physics of the American Physical Society GUEST EDITORIAL Quality & Quantity: Participation INSIDEGazette of Women and Minorities in Physics Guest Editorial By Saeqa Dil Vrtilek, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Member of CSWP 1 n January 2nd, one was unfriendly or deliberately put obstacles in my way, Oof my mainstays but it is hard to be the only one of one’s kind in any Women of Color in during graduate school environment. And I had more than gender to separate Physics Departments will visit from Berlin. me: I was small, I had dark skin, I was a foreigner, I 1 When I was a graduate spoke with an accent, I was older and already married, student, Yvonne, the de- I had an impossible name, and a not entirely amenable Minority Bridge partment administrative personality. When I emerged in 1985 with my PhD and Program is Launched assistant, was the only a US citizenship I was on top of the world. Although 2 other woman around: I regularly descend to the depths, I always come right there were no other fe- back up: Yvonne and I “made it” but not everyone African American male graduate students, does. I would wish support such as I received from Women Saeqa Dil Vrtilek no female post-docs, Yvonne for every minority, but barring that possibility, 4 and no female faculty. I believe it is numbers that matter. Yvonne was one of the thousands who work a job in At my undergraduate institution, the percent of Gender Equity New York while pursuing a career in music or the arts, female physics majors has gone from 2% when I was Conversations Project but she is one of the rare few who made it. -

History of Science Society Annual Meeting 3-6 November 2016 Atlanta, Georgia

History of Science Society Annual Meeting 3-6 November 2016 Atlanta, Georgia TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................ 2 Officers, Committees, and Program Chairs ............................ 5 Thank You to Volunteers ............................................................. 6 Dining in Atlanta .......................................................................... 7 Tips on Tipping ............................................................................ 9 Respectful Behavior Policy .......................................................11 Westin Peachtree Plaza Layout ................................................13 Book Exhibit Layout ..................................................................16 Caucuses and Interest Groups .................................................18 Program ........................................................................................24 Thursday, 3 November .......................................................26 Friday, 4 November .............................................................38 Saturday, 5 November ........................................................57 Sunday, 6 November ...........................................................76 Public Engagement Event .........................................................82 JCSEPHS Mentorship Event ..................................................84 Business Meeting Agenda .........................................................85 Advertising ...................................................................................86 -

![JASMINE JONES, Phd Contact: Jazzij [At] Umn.Edu | Web](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1252/jasmine-jones-phd-contact-jazzij-at-umn-edu-web-9631252.webp)

JASMINE JONES, Phd Contact: Jazzij [At] Umn.Edu | Web

JASMINE JONES, PhD Contact: jazzij [at] umn.edu | Web: http://seejazzwork.com SUMMARY My research addresses the sociotechnical challenges of making embedded computing socially acceptable in everyday life. My methodology includes ethnographic methods, development of novel IoT technologies, field studies, and artistic explorations. Domains: collective memory, health and wellness, assistive devices EDUCATION § University of Minnesota – Computer Science and Engineering, Minneapolis, Minnesota o Postdoctoral Researcher, 2017- present o Advisor: Dr. Svetlana Yarosh, Asst. Professor, Dept. of Computer Science and Engineering § University of Michigan - School of Information, Ann Arbor, Michigan o PhD in Information Science, 2017 o Advisor: Dr. Mark S. Ackerman, Professor, School of Information & Dept. of Computer Science o Dissertation: Crafting a Narrative Inheritance: A Design Framework for Intergenerational Family Memory § University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), Baltimore, Maryland o Bachelor of Science in Computer Science, 2012 o Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (HCI in an Intercultural Context), 2012 o Undergraduate Thesis: Visualizations for self-reflection on mouse pointer performance for older adults § University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia o Human-Computer Interaction, Feb – June 2010 HONORS, FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Academic Fellowships & Scholarships 2018 Postdoctoral Fellow, Big10 Academic Alliance Professorial Advancement Initiative (PAI) 2016 NSF/Korea National Research Foundation GROW International -

A Model for Immersive Professional Development of Future Engineers

Paper ID #28188 Project Connect – A Model for Immersive Professional Development of Future Engineers Prof. Rhonda R. Franklin, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities Rhonda R. Franklin received her B.S. Texas A&M University and M.S. and Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in Electrical Engineering. She is a Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the Uni- versity of Minnesota. Her research investigates the design of circuits, antennas, integration and packaging techniques, and characterization of electronic materials and magnetic nanomaterials for communication, biomedical and nanomedicine applications. She has co-authored over 100 referred conferences and jour- nals, five book chapters and two patents. She received the National Science Foundation’s Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and En- gineers and the 3M Untenured Faculty Award. She is active in the IEEE MTT-S (e.g. associate editor of MWCL, chaired IMS TPRC sub-committees, student paper competitions and scholarship committee) and is a co-founder of IMS Project Connect and Chair of MTT-S Technical Coordinating Committee for Integration and Packaging. She is the 2014 Sara Evans Faculty Scholar Leader Award, 2017 John Tate Advising Award, and 2018 Willie Hobbs Moore Distinguished Alumni Lecture Award and the 2019 IEEE N. Walter Cox Service Award recipient from the MTT-S Society. She also creates professional develop- ment programs for women and minority faculty and has served on the inaugural Women Faculty Cabinet at the University of Minnesota. Dr. Kristen S Gorman, University of Minnesota Kris Gorman is an Education Program Specialist at the University of Minnesota Center for Educational Innovation and served as external evaluator for this project. -

University of Michigan History

University of Michigan History Table of Contents Guides ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 Academics ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Administration .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Alumni ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Athletics .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Buildings & Grounds .............................................................................................................................. 11 Faculty .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Students ................................................................................................................................................... 16 Units ........................................................................................................................................................ 18 Timelines ................................................................................................................................................... -

Eleni Gourgou, CV

Eleni Gourgou, CV Eleni Gourgou , PhD 3540 G. G. Brown Laboratory Assistant Research Scientist 2350 Hayward Street Mechanical Engineering Department Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2125 College of Engineering [email protected] University of Michigan https://elenigourgou.engin.umich.edu Education~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 2011: Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Animal 2003: B.S. in Biology; Department of Biology, Physiology; Department of Biology, National National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. Greece. Thesis: “Signal transduction mechanisms in Research Thesis: “On the relation between marine invertebrates”. Advisor: C. Gaitanaki. energetics and tail autotomy capacity in greek [lizard] species of the genus Podarcis ”. Advisor: E. Valakos. Research Interests ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Neurobiology of memory and learning; Behavioral neurogenetics; Use of controlled, engineered microenvironments to interrogate the nervous system; Mathematical models of biological systems; Locomotion dynamics; Technology (3D printing, microfluidics, nanoparticles) and engineering (image processing, computer vision, data analytics) applications on neurobiology; Multi-scale dynamics of biological systems, emphasis on neurons and neuronal circuits; Neuronal physiology and calcium dynamics; Cell physiology, signal transduction and stress. Academic Positions ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ University -

A Year in Review Artwork by Rose Anderson

A Year in Review Artwork by Rose Anderson EDITORS: ADDITIONAL STORY AND Catharine June PHOTO CONTRIBUTORS: Steven Crang Bentley Historical Library Nicole Casal Moore Gabe Cherry Marcin Szczepansk Robert Coelius Joseph Xu ASSISTANT EDITORS: Katherine McAlpine Electrical and Computer Engineering Zach Champion Electrical Engineering and Hayley Hanway Computer Science Building Rose Anderson 1301 Beal Avenue The Regents of the University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2122 Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor Computer Science and Engineering Rose Anderson Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor Mark S. Schlissel (ex officio) Bob and Betty Beyster Building Shauna Ryder Diggs, Grosse Pointe 2260 Hayward Street A Non-discriminatory, Affirmative Action Employer. © 2019 Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2121 2 CONTENTS Research Briefs 5 Student News 66 TECH TRANSFER 35 Honors and Awards 75 New Doctorates Awarded 77 Department News 37 Alumni News 80 Diversity 46 Alumni Spotlights 80 New Courses + Books 48 Alumni Briefs 86 Retirements 50 Faculty News 53 New Faculty 53 Faculty Honors, Awards, and Activities 55 CSE Advisory Board New Appointments 65 and ECE Council 88 Donor News 89 In Memoriam 92 EECS Faculty Directory 94 3 Message from thE Mingyan Liu, Chair Brian Noble, Chair ChairS Electrical and Computer Computer Science Engineering and Engineering Dear Friends, The new academic year has begun, and we are delighted to Awards, and a Sloan Research Fellowship. We congratulate have our new and returning students in the halls and in our these faculty for receiving such notable endorsements of their classrooms.