Unnecessary Roughness: the NFL's History of Domestic Violence and the Need for Immediate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Awards National Football Foundation Post-Season & Conference Honors

NATIONAL AWARDS National Football Foundation Coach of the Year Selections wo Stanford coaches have Tbeen named Coach of the Year by the American Football Coaches Association. Clark Shaughnessy, who guid- ed Stanford through a perfect 10- 0 season, including a 21-13 win over Nebraska in the Rose Bowl, received the honor in 1940. Chuck Taylor, who directed Stanford to the Pacific Coast Championship and a meeting with Illinois in the Rose Bowl, was selected in 1951. Jeff Siemon was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2006. Hall of Fame Selections Clark Shaughnessy Chuck Taylor The following 16 players and seven coaches from Stanford University have been selected to the National Football Foundation/College Football Hall of Fame. Post-Season & Conference Honors Player At Stanford Enshrined Heisman Trophy Pacific-10 Conference Honors Ernie Nevers, FB 1923-25 1951 Bobby Grayson, FB 1933-35 1955 Presented to the Most Outstanding Pac-10 Player of the Year Frank Albert, QB 1939-41 1956 Player in Collegiate Football 1977 Guy Benjamin, QB (Co-Player of the Year with Bill Corbus, G 1931-33 1957 1970 Jim Plunkett, QB Warren Moon, QB, Washington) Bob Reynolds, T 1933-35 1961 Biletnikoff Award 1980 John Elway, QB Bones Hamilton, HB 1933-35 1972 1982 John Elway, QB (Co-Player of the Year with Bill McColl, E 1949-51 1973 Presented to the Most Outstanding Hugh Gallarneau, FB 1938-41 1982 Receiver in Collegiate Football Tom Ramsey, QB, UCLA 1986 Brad Muster, FB (Offensive Player of the Year) Chuck Taylor, G 1940-42 1984 1999 Troy Walters, -

Congressional Record—Senate S13621

November 2, 1999 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE S13621 message from the Chicago Bears. Many ex- with him. You could tell he was very The last point I will make is, toward ecutives knew what it said before they read genuine.'' the end of his life when announcing he it: Walter Payton, one of the best ever to Bears fans in Chicago felt the same way, faced this fatal illness, he made a plea which is why reaction to his death was swift play running back, had died. across America to take organ donation For the past several days it has been ru- and universal. mored that Payton had taken a turn for the ``He to me is ranked with Joe DiMaggio in seriously. He needed a liver transplant worse, so the league was braced for the news. baseballÐhe was the epitome of class,'' said at one point in his recuperation. It Still, the announcement that Payton had Hank Oettinger, a native of Chicago who was could have made a difference. It did not succumbed to bile-duct cancer at 45 rocked watching coverage of Payton's death at a bar happen. and deeply saddened the world of profes- on the city's North Side. ``The man was such I do not know the medical details as sional football. a gentleman, and he would show it on the to his passing, but Walter Payton's ``His attitude for life, you wanted to be football field.'' message in his final months is one we around him,'' said Mike Singletary, a close Several fans broke down crying yesterday as they called into Chicago television sports should take to heart as we remember friend who played with Payton from 1981 to him, not just from those fuzzy clips of 1987 on the Bears. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

2 Den at Chi 08 16 2003 Fli

Denver Broncos vs Chicago Bears Saturday, August 16, 2003 at Memorial Stadium BEARS BEARS OFFENSE BEARS DEFENSE BRONCOS No Name Pos WR 80 D.White 83 D.Terrell 87 J.Elliott LE 93 P.Daniels 99 J.Tafoya 63 C.Demaree No Name Pos 10 Stewart,Kordell QB WR 16 E.Shepherd 18 J.Gage LT 92 T.Washington 70 A.Boone 71 I.Scott 1 Elam,Jason K 11 Barnard,Brooks P 11 Beuerlein,Steve QB 12 Chandler,Chris QB LT 69 M.Gandy 60 T.Metcalf 63 P.Lougheed RT 98 B.Robinson 94 K.Traylor 72 E.Grant 12 Adams,Charlie WR 15 Forde,Andre WR LG 64 R.Tucker 73 S.Grice 62 T.Vincent DT 73 T.LaFavor 67 T.Benford 13 Madise,Adrian WR 16 Shepherd,Edell WR 14 Jackson,Nate WR 17 Sauter,Cory QB C 57 O.Kreutz 74 B.Robertson 67 J.Warner RE 96 A.Brown 97 M.Haynes 76 B.Setzer 15 Rice,Frank WR 18 Gage,Justin WR RG 58 C.Villarrial 67 J.Warner 68 B.Anderson WLB 53 W.Holdman 55 M.Caldwell 59 J.Odom 16 Plummer,Jake QB 19 Thurmon,Elijah WR 17 Jackson,Jarious QB 2 Edinger,Paul K RG 76 J.Grzeskowiak 71 J.Soriano MLB 54 B.Urlacher 52 B.Howard 62 J.Schumacher 2 Rolovich,Nick QB 20 Williams,Roosevelt CB RT 78 A.Gibson 79 S.Edwards 75 M.Colombo SLB 90 B.Knight 91 L.Briggs 55 M.Caldwell 20 Jackson,Marlion RB 21 McQuarters,R.W. CB 21 Kelly,Ben CB 22 Hicks,Maurice RB TE 88 D.Clark 89 D.Lyman 85 J.Gilmore LCB 21 R.McQuarters 20 R.Williams 46 J.Goss 22 Griffin,Quentin RB 23 Azumah,Jerry CB TE 46 B.Fletcher 49 M.Afariogun 82 J.Davis LCB 26 T.McMillon 24 E.Joyce 23 Middlebrooks,Willie CB 24 Joyce,Eric CB 24 O'Neal,Deltha CB 25 Gray,Bobby SS TE 48 R.Johnson RCB 23 J.Azumah 33 C.Tillman 39 T.Gaines 25 Ferguson,Nick -

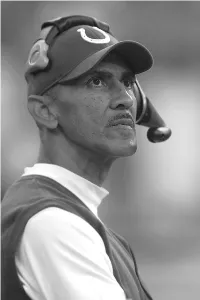

Quiet Strength a MEMOIR Tony Dungy with Nathan Whitaker

QStreng.indd 4 11/18/2010 1:24:45 PM quiet strength A MEMOIR tony dungy with nathan whitaker TYND ALE HOUSE PUBLISHERS, INC. CAR OL STREAM, ILLINOIS QStreng.indd 5 11/18/2010 1:24:47 PM Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com TYNDALE and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Quiet Strength: The Principles, Practices, & Priorities of a Winning Life Copyright © 2007 by Tony Dungy. All rights reserved. Cover photos courtesy of the Indianapolis Colts. Reprinted with permission. Interior photo of Tony with CleoMae Dungy copyright © by Jackson Citizen Patriot 2007. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. Interior photo of Tony with Coach Cal Stoll copyright © by Wendell Vandersluis/University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. Interior photo of Tony in Steelers uniform copyright © by George Gojkovich/Contributor/Getty Images. All rights reserved. Interior black and white Steelers photo of Tony with Chuck Noll copyright © by the Pittsburgh Steelers/ Mike Fabus. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. Interior photo of Tony and Lauren Dungy copyright © by Boyzell Hosey/St. Petersburg Times. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. Interior photo of Tony speaking at Family First event courtesy of All Pro Dad. Reprinted with permission. Interior photo of Tony and Lauren Dungy with Dr. and Mrs. Carson courtesy of Carson Scholars Fund, Inc. Interior photo of Tiara Dungy and Lisa Harris copyright © by Mike Patton. All rights reserved. Interior locker room prayer photo copyright © by Donald Miralle/Getty Images. All rights reserved. Interior photo of Dungy family on plane courtesy of Richard Howell. -

Fewer Hands, More Mercy: a Plea for a Better Federal Clemency System

FEWER HANDS, MORE MERCY: A PLEA FOR A BETTER FEDERAL CLEMENCY SYSTEM Mark Osler*† INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 465 I. A SWAMP OF UNNECESSARY PROCESS .................................................. 470 A. From Simplicity to Complexity ....................................................... 470 B. The Clemency System Today .......................................................... 477 1. The Basic Process ......................................................................... 477 a. The Pardon Attorney’s Staff ..................................................... 478 b. The Pardon Attorney ................................................................ 479 c. The Staff of the Deputy Attorney General ................................. 481 d. The Deputy Attorney General ................................................... 481 e. The White House Counsel Staff ................................................ 483 f. The White House Counsel ......................................................... 484 g. The President ............................................................................ 484 2. Clemency Project 2014 ................................................................ 485 C. The Effect of a Bias in Favor of Negative Decisions ...................... 489 II. BETTER EXAMPLES: STATE AND FEDERAL .......................................... 491 A. State Systems ................................................................................... 491 1. A Diversity -

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Apr. 26, 2003 DALLAS—Big 12 Conference teams had 10 of the first 62 selections in the 35th annual NFL “common” draft (67th overall) Saturday and added a total of 13 for the opening day. The first-day tallies in the 2003 NFL draft brought the number Big 12 standouts taken from 1995-03 to 277. Over 90 Big 12 alumni signed free agent contracts after the 2000-02 drafts, and three of the first 13 standouts (six total in the first round) in the 2003 draft were Kansas State CB Terence Newman (fifth draftee), Oklahoma State DE Kevin Williams (ninth) Texas A&M DT Ty Warren (13th). Last year three Big 12 standouts were selected in the top eight choices (four of the initial 21), and the 2000 draft included three alumni from this conference in the first 20. Colorado, Nebraska and Florida State paced all schools nationally in the 1995-97 era with 21 NFL draft choices apiece. Eleven Big 12 schools also had at least one youngster chosen in the eight-round draft during 1998. Over the last six (1998-03) NFL postings, there were 73 Big 12 Conference selections among the Top 100. There were 217 Big 12 schools’ grid representatives on 2002 NFL opening day rosters from all 12 members after 297 standouts from league members in ’02 entered NFL training camps—both all-time highs for the league. Nebraska (35 alumni) was third among all Division I-A schools in 2002 opening day roster men in the highest professional football configuration while Texas A&M (30) was among the Top Six in total NFL alumni last autumn. -

Admission Promotion Offered to Steelers & Vikings Fans

Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE @ProFootballHOF 09/14/2017 Contact: Pete Fierle, Chief of Staff & Vice President of Communications [email protected]; 330-588-3622 ADMISSION PROMOTION OFFERED TO STEELERS & VIKINGS FANS FANS OF WEEK 2 MATCH-UP TO RECEIVE SPECIAL HALL OF FAME ADMISSION DISCOUNT FOR WEARING TEAM GEAR CANTON, OHIO – The Pro Football Hall of Fame is inviting Pittsburgh Steelers and Minnesota Vikings fans to experience “The Most Inspiring Place on Earth!” The Steelers host the Vikings on Sunday (Sept. 17) at 1:00 p.m. at Heinz Field. The Pro Football Hall of Fame is located two hours west of Pittsburgh. Any Steelers or Vikings fan dressed in their team’s gear who mentions the promotion at the Hall’s Ticket Office will receive a $5 discount on any regular price museum admission. Vikings fans may receive the discount now through Monday, Sept. 18. The promotion runs all season long for Steelers fans ending Jan. 1, 2018. The Hall of Fame is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. Information about planning a visit to the Hall of Fame can be found at: www.ProFootballHOF.com/visit/. VIKINGS IN CANTON The Minnesota franchise has 13 longtime members enshrined in the Hall of Fame. They include: CRIS CARTER (Wide Receiver, 1990-2001, Class of 2013); CHRIS DOLEMAN (Defensive End-Linebacker, 1985-1993, 1999, Class of 2012); CARL ELLER (Defensive End, 1964-1978, Class of 2004); JIM FINKS (Administrator, 1964-1973, Class of 1995); BUD GRANT (Coach, 1967-1983, 1985, Class of 1994); PAUL KRAUSE (Safety, 1968-1979, Class of 1998); RANDALL McDANIEL (Guard, 1988- 1999, Class of 2009); ALAN PAGE (Defensive Tackle, 1967-1978, Class of 1988); JOHN RANDLE (Defensive Tackle, 1990-2000, Class of 2010); FRAN TARKENTON (Quarterback, 1961-66, 1972-78, Class of 1986); MICK TINGELHOFF (Center, 1962- 1978, Class of 2015); RON YARY (Tackle, 1968-1981, Class of 1983) and GARY ZIMMERMAN (Tackle, 1986-1992, Class of 2008). -

"The Olympics Don't Take American Express"

“…..and the Olympics didn’t take American Express” Chapter One: How ‘Bout Those Cowboys I inherited a predisposition for pain from my father, Ron, a born and raised Buffalonian with a self- mutilating love for the Buffalo Bills. As a young boy, he kept scrap books of the All American Football Conference’s original Bills franchise. In the 1950s, when the AAFC became the National Football League and took only the Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and Baltimore Colts with it, my father held out for his team. In 1959, when my father moved the family across the country to San Jose, California, Ralph Wilson restarted the franchise and brought Bills’ fans dreams to life. In 1960, during the Bills’ inaugural season, my father resumed his role as diehard fan, and I joined the ranks. It’s all my father’s fault. My father was the one who tapped his childhood buddy Larry Felser, a writer for the Buffalo Evening News, for tickets. My father was the one who took me to Frank Youell Field every year to watch the Bills play the Oakland Raiders, compliments of Larry. By the time I had celebrated Cookie Gilcrest’s yardage gains, cheered Joe Ferguson’s arm, marveled over a kid called Juice, adapted to Jim Kelly’s K-Gun offense, got shocked by Thurman Thomas’ receptions, felt the thrill of victory with Kemp and Golden Wheels Dubenion, and suffered the agony of defeat through four straight Super Bowls, I was a diehard Bills fan. Along with an entourage of up to 30 family and friends, I witnessed every Super Bowl loss. -

Final Rosters

Rosters 2001 Final Rosters Injury Statuses: (-) = OK; P = Probable; Q = Questionable; D = Doubtful; O = Out; IR = On IR. Baltimore Hownds Owner: Zack Wilz-Knutson PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. Houston Stallions Owner: Ian Wilz PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR Dave Brown QB ARI - Jake Plummer QB ARI - Tim Couch QB CLE - Duce Staley RB PHI - Ricky Watters RB SEA IR Ron Dayne RB NYG - Stanley Pritchett RB CHI - Zack Crockett RB OAK - Derrick Mason WR TEN - Johnnie Morton WR DET - Laveranues Coles WR NYJ - Willie Jackson WR NOR - Alge Crumpler TE ATL - Dave Moore TE TAM - Matt Stover K BAL - Paul Edinger K CHI - 2001 Final Rosters 1 Rosters Chicago Bears Defense CHI - Pittsburgh Steelers Defense PIT - Carolina Panthers Special Team CAR - Dallas Cowboys Special Team DAL - Dan Reeves Head Coach ATL - Dick Jauron Head Coach CHI - NYC Dark Force Owner: D.J. Wendell NFL ON PLAYER POSITION INJ STARTER RESERVE TEAM IR Aaron Brooks QB NOR - Daunte Culpepper QB MIN - Jeff Blake QB NOR - Bob Christian RB ATL - Emmitt Smith RB DAL - James Stewart RB DET - Jim Kleinsasser RB MIN - Warrick Dunn RB TAM - Cris Carter WR MIN - James Thrash WR PHI - Jerry Rice WR OAK - Travis Taylor WR BAL - Dwayne Carswell TE DEN - Jay Riemersma TE BUF - Jay Feely K ATL - Joe Nedney K TEN - San Francisco 49ers Defense SFO - Defense TAM - 2001 Final Rosters 2 Rosters Tampa Bay Buccaneers Minnesota Vikings Special Team MIN - Oakland Raiders Special Team OAK - Dick Vermeil Head Coach KAN - Steve Mariucci Head Coach SFO - Las Vegas Owner: ?? PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. -

Front Page Logo

The Presorted Standard U.S. Postage Paid Austin, Texas Permit No. 01949 Circulation Villager Verification Council This paper can A community service weekly Since 1973 be recycled 1223-A Rosewood Avenue Austin, Texas 78702 TPA Vol. 36 No. 24 Website: theaustinvillager.com Email: [email protected] Phone: 512-476-0082 Fax: 512-476-0179 November 7, 2008 Councilman Mr. President!! Martinez offers a solution to transit labor negotiations Austin City Council Member Mike Martinez today was joined by elected officials and community leaders at Plaza Saltillo to propose an alternative to the current con- tract being negotiated be- RAPPIN’ tween Star Tran and Amal- Tommy Wyatt gamated Transit Union (ATU), Local 1091. Last week the ATU announced a work Now the stoppage by its members be- ginning Nov. 5. work begins! The proposed plan is for No one can doubt that two years (July 2007 - July November 4, 2008 will go 2009) with a retroactive pay down as a turning point in increase of 3 % for 2007 - 2008 America. The election of and an increase of 2.5% for Barack Obama raised our 2008-2009. status at home and abroad. Other components of American image has the plan include: been tarnished in the last * Accept Star Tran’s few years, because of our proposed health care package arrogant attitude and our * Eliminate proposed belief that we have the right tiered wage system to tell everyone else in the * Conduct an indepen- world how to handle their dent audit of Capital Metro by affairs. And we have not a mutually agreed upon au- been shy about inserting our ditor to be completed prior to will and beliefs in the af- July 2009 fairs of other countries Council Member when they do not operate Martinez asked ATU mem- according to our standards. -

2011 GATORS in the NFL 35 Players, 429 Games Played, 271

2012 FLORIDA FOOTBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS 2012 SCHEDULE COACHES Roster All-Time Results September 2-3 Roster 107-114 Year-by-Year Scores 1 Bowling Green Gainesville, Fla. 115-116 Year-by-Year Records 8 at Texas A&M* College Station, Texas Coaching Staff 117 All-Time vs. Opponents 15 at Tennessee* Knoxville, Tenn. 4-7 Head Coach Will Muschamp 118-120 Series History vs. SEC, FSU, Miami 22 Kentucky* Gainesville, Fla. 10 Tim Davis (OL) 121-122 Ben Hill Griffin Stadium at Florida Field 29 Bye 11 D.J. Durkin (LB/Special Teams) 123-127 Miscellaneous History PLAYERS 12 Aubrey Hill (WR/Recruiting Coord.) 128-138 Bowl Game History October 13 Derek Lewis (TE) 6 LSU* Gainesville, Fla. 14 Brent Pease (Offensive Coord./QB) Record Book 13 at Vanderbilt* Nashville, Tenn. 15 Dan Quinn (Defensive Coord./DL) 139-140 Year-by-Year Stats 20 South Carolina* Gainesville, Fla. 16 Travaris Robinson (DB) 141-144 Yearly Leaders 27 vs. Georgia* Jacksonville, Fla. 17 Brian White (RB) 145 Bowl Records 18 Bryant Young (DL) 146-148 Rushing November 19 Jeff Dillman (Director of Strength & Cond.) 149-150 Passing 3 Missouri* Gainesville, Fla. 2011 RECAP 19 Support Staff 151-153 Receiving 10 UL-Lafayette (Homecoming) Gainesville, Fla. 154 Total Offense 17 Jacksonville State Gainesville, Fla. 2012 Florida Gators 155 Kicking 24 at Florida State Tallahassee, Fla. 20-45 Returning Player Bios 156 Returns, Scoring 46-48 2012 Signing Class 157 Punting December 158 Defense 1 SEC Championship Atlanta, Ga. 2011 Season Review 160 National and SEC Record Holders *Southeastern Conference Game HISTORY 49-58 Season Stats 161-164 Game Superlatives 59-65 Game-by-Game Review 165 UF Stat Champions 166 Team Records CREDITS Championship History 167 Season Bests The official 2012 University of Florida Football Media Guide has 66-68 National Championships 168-170 Miscellaneous Charts been published by the University Athletic Association, Inc.