Platform – Journal of Media and Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rob Mills Became a Household Name on Australian Idol. Now He's Starring

Wicked boy “I don’t mind male attention. It’s a bit of fun,” says Rob Mills. Rob Mills became a household name on Australian Idol. watched that show? No, I’ve never seen it, and I don’t think she Now he’s starring in Wicked and living the musical theatre likes talking about it too much. She doesn’t dream. From nude scenes to selling his used G-strings, bring it up, so I choose to avoid it. Millsy reveals all to Matt Myers. Prisoner has a big gay cult following. I’ve heard she was a pretty terrifying lady DNA: You’ve played Fiyero in Wicked for a so I’ll definitely be auditioning for Corny in Prisoner. I can tell you now, she’s just as year now. What has the experience been like? Collins at least. terrifying as Madame Morrible in Wicked! Rob Mills: It’s a dream come true! I’ve wanted You played Claude in the 2007 production of That’s probably why she’s got a Helpman to play this part for the past three years and Hair. Did you end up going nude? nomination. She just owns that character. now that I’m doing it, it’s a great rush. Fiyero The part where that happens is where my She has a powerful presence on the stage is a great character and I get to work with character sings, “Where do I go? Follow and is a tremendous actor. Maggie’s helped some amazing stars. Bert Newton’s joined us the river…” In most productions they hold me heaps. -

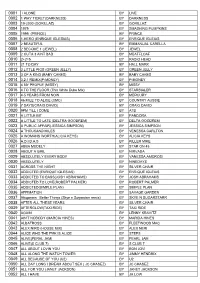

ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2011 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2011 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 MAKING MIRRORS Gotye <P>2 ELEV/UMA ELEVENCD101 2 REECE MASTIN Reece Mastin <P> SME 88691916002 3 THE BEST OF COLD CHISEL - ALL FOR YOU Cold Chisel <P> WAR 5249889762 4 ROY Damien Leith <P> SME 88697892492 5 MOONFIRE Boy & Bear <P> ISL/UMA 2777355 6 RRAKALA Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu <G> SFM/MGM SFGU110402 7 DOWN THE WAY Angus & Julia Stone <P>3 CAP/EMI 6263842 8 SEEKER LOVER KEEPER Seeker Lover Keeper <G> DEW/UMA DEW9000330 9 THE LIFE OF RILEY Drapht <G> AYEM/SME AYEMS001 10 BIRDS OF TOKYO Birds Of Tokyo <P> CAP/EMI 6473012 11 WHITE HEAT: 30 HITS Icehouse <G> DIVA/UMA DIVAU1015C 12 BLUE SKY BLUE Pete Murray <G> SME 88697856202 13 TWENTY TEN Guy Sebastian <P> SME 88697800722 14 FALLING & FLYING 360 SMR/EMI SOLM8005 15 PRISONER The Jezabels <G> IDP/MGM JEZ004 16 YES I AM Jack Vidgen <G> SME 88697968532 17 ULTIMATE HITS Lee Kernaghan ABC/UMA 8800919 18 ALTIYAN CHILDS Altiyan Childs <P> SME 88697818642 19 RUNNING ON AIR Bliss N Eso <P> ILL/UMA ILL034CD 20 THE VERY VERY BEST OF CROWDED HOUSE Crowded House <G> CAP/EMI 9174032 21 GILGAMESH Gypsy & The Cat <G> SME 88697806792 22 SONGS FROM THE HEART Mark Vincent SME 88697927992 23 FOOTPRINTS - THE BEST OF POWDERFINGER 2001-2011 Powderfinger <G> UMA 2777141 24 THE ACOUSTIC CHAPEL SESSIONS John Farnham SME 88697969872 25 FINGERPRINTS & FOOTPRINTS Powderfinger UMA 2787366 26 GET 'EM GIRLS Jessica Mauboy <G> SME 88697784472 27 GHOSTS OF THE PAST Eskimo Joe WAR 5249871942 28 TO THE HORSES Lanie Lane IVY/UMA IVY121 29 GET CLOSER Keith Urban <G> CAP/EMI 9474212 30 LET'S GO David Campbell SME 88697987582 31 THE ENDING IS JUST THE BEGINNING REPEATING The Living End <G> DEW/UMA DEW9000353 32 THE EXPERIMENT Art vs. -

Aussie Classics Hits - 180 Songs

Available from Karaoke Home Entertainment Australia and New Zealand Aussie Classics Hits - 180 Songs 1 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 2 Absolutely Everybody Vanessa Amorosi 3 Age Of Reason John Farnham 4 All I Do Daryl Braithwaite 5 All My Friends Are Getting Married Skyhooks 6 Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again The Angels 7 Amazing Alex Lloyd 8 Amazing Vanessa Amorosi 9 Animal Song Savage Garden 10 April Sun In Cuba Dragon 11 Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet 12 Art Of Love Guy Sebastian, Jordin Sparks 13 Aussie Rules I Thank You For The Best Kevin Johnson Years Of Our Lives 14 Australian Boy Lee Kernaghan 15 Barbados The Models 16 Battle Scars Guy Sebastian, Lupe Fiasco 17 Bedroom Eyes Kate Ceberano 18 Before The Devil Knows You're Dead Jimmy Barnes 19 Before Too Long Paul Kelly, The Coloured Girls 20 Better Be Home Soon Crowded House 21 Better Than John Butler Trio 22 Big Mistake Natalie Imbruglia 23 Black Betty Spiderbait 24 Bluebird Kasey Chambers 25 Bopping The Blues Blackfeather 26 Born A Woman Judy Stone 27 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 28 Bow River Cold Chisel 29 Boys Will Be Boys Choir Boys 30 Breakfast At Sweethearts Cold Chisel 31 Burn For You John Farnham 32 Buses And Trains Bachelor Girl 33 Chained To The Wheel Black Sorrows 34 Cheap Wine Cold Chisel 35 Come On Aussie Come On Shannon Noll 36 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 37 Compulsory Hero 1927 38 Cool World Mondo Rock 39 Crazy Icehouse 40 Cry In Shame Johnny Diesel, The Injectors 41 Dancing With A Broken Heart Delta Goodrem 42 Devil Inside Inxs 43 Do It With Madonna The Androids 44 -

Sydney Law Review

volume 40 number 1 march 2018 the sydney law review articles The Noongar Settlement: Australia’s First Treaty – Harry Hobbs and George Williams 1 Taking the Human Out of the Regulation of Road Behaviour – Chris Dent 39 Financial Robots as Instruments of Fiduciary Loyalty – Simone Degeling and Jessica Hudson 63 “Restoring the Rule of Law” through Commercial (Dis)incentives: The Code for the Tendering and Performance of Building Work 2016 – Anthony Forsyth 93 In Whose Interests? Fiduciary Obligations of Union Officials in Bargaining – Jill Murray 123 review essay Critical Perspectives on the Uniform Evidence Law – James D Metzger 147 EDITORIAL BOARD Elisa Arcioni (Editor) Celeste Black (Editor) Emily Hammond Fady Aoun Sheelagh McCracken Emily Crawford Tanya Mitchell John Eldridge Michael Sevel Jamie Glister Cameron Stewart Book Review Editor: John Eldridge Before the High Court Editor: Emily Hammond Publishing Manager: Cate Stewart Editing Assistant: Brendan Hord Correspondence should be addressed to: Sydney Law Review Law Publishing Unit Sydney Law School Building F10, Eastern Avenue UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Website and submissions: <https://sydney.edu.au/law/our-research/ publications/sydney-law-review.html> For subscriptions outside North America: <http://sydney.edu.au/sup/> For subscriptions in North America, contact Gaunt: [email protected] The Sydney Law Review is a refereed journal. © 2018 Sydney Law Review and authors. ISSN 0082–0512 (PRINT) ISSN 1444–9528 (ONLINE) The Noongar Settlement: Australia’s First Treaty Harry Hobbs and George Williams† Abstract There has been a resurgence in debate over the desirability and feasibility of a treaty between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and the Australian State. -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

2014 Annual Report Secretary’S Introduction

2014 Annual Report Secretary’s Introduction It gives me great pleasure to present the 2014 annual report. A highlight of 2014 was bringing our work at Unions NSW under a unifying agenda of Jobs, Rights, Services. This ensures we have a constant thread to all we do at Unions NSW. The contrast between our positive agenda and that of the conservatives was evident to all when the federal budget was handed down in May. Its attack on Medicare, pensions, university fees and other aspects of the social wage was a move by the federal government to take the nation down a new road of user pays. The response to the budget from the NSW union movement was magnificent. Actions included regional meetings, acquiring over 11,000 signatures on our petition, and a combined delegates meeting of over 400. This culminated in the Bust the Budget rally in Sydney Square on July 6 attended by around 10,000 people. Our actions together with those of unionists around the country were crucial in ensuring many of the budget measures were defeated. In NSW the Baird government continued pursing its version of the conservative agenda most notably through its moves to privatise the states assets and services. In electricity, health and education, to name a just a few areas, the state government made it clear that their way forward for NSW is to privatise assets and services either by sale or outsourcing. The response by unions to the government’s various announcements was very strong and will continue in 2015. In addition, the obvious inequity of the state government’s workers compensation system was again highlighted with further cuts in 2014 to the employer’s premiums. -

Bond University Indigenous Gala Friday 16 November, 2018 Bond University Indigenous Program Partners

Bond University Indigenous Gala Friday 16 November, 2018 Bond University Indigenous Program Partners Bond University would like to thank Dr Patrick Corrigan AM and the following companies for their generous contributions. Scholarship Partners Corporate Partners Supporting Partners Event Partners Gold Coast Professor Elizabeth Roberts Jingeri Thank you for you interest in supporting the valuable Indigenous scholarship program offered by Bond University. The University has a strong commitment to providing educational opportunities and a culturally safe environment for Indigenous students. Over the past several years the scholarship program has matured and our Indigenous student cohort and graduates have flourished. We are so proud of the students who have benefited from their scholarship and embarked upon successful careers in many different fields of work. The scholarship program is an integral factor behind these success stories. Our graduates are important role models in their communities and now we are seeing the next generation of young people coming through, following in the footsteps of the students before them. It is my honour and privilege to witness our young people receiving the gift of education, and I thank you for partnering with us to create change. Aunty Joyce Summers Bond University Fellow 3 Indigenous Gala Patron Dr Patrick Corrigan AM Dr Patrick Corrigan AM is one of Australia’s most prodigious art collectors and patrons. Since 2007, he has personally donated or provided on loan the outstanding ‘Corrigan’ collection on campus, which is Australia’s largest private collection of Indigenous art on public display. Dr Corrigan has been acknowledged with a Member of the Order of Australia (2000), Queensland Great medal (2014) and City of Gold Coast Keys to the City award (2015) for his outstanding contributions to the arts and philanthropy. -

ARIA TOP 20 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2005 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 20 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST ALBUMS CHART 2005 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 THE SOUND OF WHITE Missy Higgins <P>8 ELEV/EMI ELEVENCD27 2 ANTHONY CALLEA Anthony Callea <P>2 SBME 82876685972 3 SEE THE SUN Pete Murray <P>2 COL/SBME 82876724782 4 AWAKE IS THE NEW SLEEP Ben Lee <P>2 INERTIA IR5210CD 5 TEA AND SYMPATHY Bernard Fanning <P>2 DEW/UMA DEW90172 6 MISTAKEN IDENTITY Delta Goodrem <P>5 EPI/SBME 5189152000 7 REACH OUT: THE MOTOWN RECORD Human Nature <P>3 COL/SBME 82876736392 8 TWO SHOES The Cat Empire <P> EMI 3112212 9 GET BORN Jet <P>8 CAP/EMI 5942002 10 ULTIMATE KYLIE Kylie Minogue <P>2 FMR/WAR 338372 11 LIFT Shannon Noll <P>2 SBME 82876740522 12 THIRSTY MERC Thirsty Merc <P> WEA/WAR 5046788632 13 SHE WILL HAVE HER WAY - THE SONGS OF TIM & NEIL FINN Various CAP/EMI 3404952 14 DOUBLE HAPPINESS Jimmy Barnes <P> LIB/WAR LIBCD71523 15 FINGERPRINTS: THE BEST OF Powderfinger <P>2 UMA 9823521 16 TOGETHER IN CONCERT - JOHN FARNHAM & TOM JONES John Farnham & Tom Jones <P> SBME 82876682212 17 I REMEMBER WHEN I WAS YOUNG - SONGS FROM THE GR… John Farnham <P>2 SBME 82876747652 18 THE SECRET LIFE OF... The Veronicas <P> WARNER 9362493712 19 THE CRUSADER Scribe <P> FMR/WAR 338745 20 SUNRISE OVER SEA The John Butler Trio <P>4 JAR/MGM JBT006 © 1988-2006 Australian Recording Industry Association Ltd. -

Christian Porter

Article Talk Read View source View history Search Wikipedia Christian Porter From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Citation bot (talk | contribs) at 17:14, 25 February 2021 (Add: work. Removed parameters. Main page Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by AManWithNoPlan | Pages linked from Contents cached User:AManWithNoPlan/sandbox2 | via #UCB_webform_linked 268/1473). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this Current events revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision. Random article (diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) About Wikipedia Contact us For the singer, see The Voice (U.S. season 4). Donate Charles Christian Porter (born 11 July 1970) is an Australian Liberal Party politician and Contribute The Honourable lawyer serving as Attorney-General of Australia since 2017, and has served as Member of Christian Porter Help Parliament (MP) for Pearce since 2013. He was appointed Minister for Industrial Relations MP Learn to edit and Leader of the House in 2019. Community portal Recent changes From Perth, Porter attended Hale School, the University of Western Australia and later the Upload file London School of Economics, and practised law at Clayton Utz and taught law at the University of Western Australia before his election to parliament. He is the son of the 1956 Tools Olympic silver medallist, Charles "Chilla" Porter, and the grandson of Queensland Liberal What links here politician, Charles Porter, who was a member of the Queensland Legislative Assembly from Related changes [4][5] Special pages 1966 to 1980. -

"Weird Al" Yankovic

"Weird Al" Yankovic - Ebay Abba - Take A Chance On Me `M` - Pop Muzik Abba - The Name Of The Game 10cc - The Things We Do For Love Abba - The Winner Takes It All 10cc - Wall Street Shuffle Abba - Waterloo 1927 - Compulsory Hero ABC - Poison Arrow 1927 - If I Could ABC - When Smokey Sings 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Long Way To The Top 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Thunderstruck 30h!3 - Don't Trust Me Ac Dc - You Shook Me All Night Long 3Oh!3 feat. Katy Perry - Starstrukk AC/DC - Rocker 5 Star - Rain Or Shine Ac/dc - Back In Black 50 Cent - Candy Shop AC/DC - For Those About To Rock 50 Cent - Just A Lil' Bit AC/DC - Heatseeker A.R. Rahman Feat. The Pussycat Dolls - Jai Ho! (You AC/DC - Hell's Bells Are My Destiny) AC/DC - Let There Be Rock Aaliyah - Try Again AC/DC - Thunderstruck Abba - Chiquitita AC-DC - It's A Long Way To The Top Abba - Dancing Queen Adam Faith - The Time Has Come Abba - Does Your Mother Know Adamski - Killer Abba - Fernando Adrian Zmed (Grease 2) - Prowlin' Abba - Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) Adventures Of Stevie V - Dirty Cash Abba - Knowing Me, Knowing You Aerosmith - Dude (Looks Like A Lady) Abba - Mamma Mia Aerosmith - Love In An Elevator Abba - Super Trouper Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion A-Ha - Cry Wolf Alanis Morissette - Not The Doctor A-Ha - Touchy Alanis Morissette - You Oughta Know A-Ha - Hunting High & Low Alanis Morrisette - I see Right Through You A-Ha - The Sun Always Shines On TV Alarm - 68 Guns Air Supply - All Out Of Love Albert Hammond - Free Electric Band -

0254 CX Noll Pg46-55

ON TOUR SHANNON NOLL ON TOUR This is the Australian tour that grew, with dates added and then dates sold out. CX heard the word, the word was good, and we hit the road to see what a sellout road tour looks like. 46 CX 15th MAY 2006 www.juliusmedia.com ! WHOLE NEW ANGLE IN SOUND .EED TIGHTER COVERAGE ./02/",%- #HANGETHE DISPERSION ANGLEIN SECONDS -ODE -ODE -ODE -ODE -IXED!NGLE-ODE 7IDEST$ISPERSION 7IDE$ISPERSION 7IDEST$ISPERSION 7IDEST$ISPERSION 7IDEST$ISPERSION .EW #OMPACT ,INE !RRAY )&9/5$%3)'.!.$).34!,,30%!+%23934%-3 USINGCONVENTIONALTWO WAYBOXSPEAKERS YOU KNOWTHATPATTERNCONTROLINTHEVOICEFREQUENCY RANGE CAN BE DIFlCULT TO MANAGE ESPECIALLY IN REVERBERANT SPACES 4HE 4/! (8 OFFERS A RADICALLY DIFFERENT APPROACH TO SPEAKER DESIGN WITHFOURADJUSTABLEDISPERSIONANGLES ANDTHATYOUCANCHANGEINSECONDS "ESTOFALL YOUGETPATTERNCONTROLBELOWK(Z By JULIUS GRAFTON IN A COMPACT AND LIGHTWEIGHT ENCLOSURE THATS PERFECTFORAMULTITUDEOFAPPLICATIONS 4HINKOF hannon Noll has legs. His 2006 Lift tour covered 16,000 kilometers in 7 weeks and was mainly sold out. ITASTHEMOSTVERSATILEhBUILDINGBLOCKv SPEAKER SIf the show at Yallah Roadhouse (near Wollongong) was INYOURTOOLKIT any indication, this guy has legs like Jimmy Barnes and John Farnham. #RISP CLEAR SOUND HIGH POWER HANDLING Do the math. 1,000 punters or more, $35 per head, plus VERSATILE MOUNTING HARDWARE AND MORE merchandising. Five shows a week. They don’t travel light, those Noll boys. They cut their #ONTACT US FOR FURTHER INFORMATION OR A teeth on the Bachelor and Spinster Ball (B & S circuit) out HANDS ONDEMONSTRATION 7ETHINKYOULL west, where men are men and some would rather fight than LIKEWHATYOUHEAR feed. The average B & S is a blooding for a musician, and for crew alike.