COPY(WRITE): INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY in the WRITING CLASSROOM PERSPECTIVES on WRITING Series Editor, Susan H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reid, Alex Communications EDRS PRICE on Technology. Now

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 062 803 EM 009 846 AUTHOR Reid, Alex TITLE New Directio:Is inTelecommunications Research. INSTITUTION Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, New York,N.Y. PUB DATE Jun 71 NOTE 62p.; Report of the SloanCommission cn Cable Communications EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTCRS Cable Television; City Planning;Communications; Human Engineering; InformationSystems; Information Theory; Man Machine Systems; *MediaResearch; *Research Needs; *Telecommunication;Telephone Communications Industry IDENTIFIERS *Sloan Commission on CableCommunications ABSTRACT Telecommunications research has been focusedmainly on technology. Nowresearch about the human factorsis crucial. This can be divided intofour areas.(1) TLe needs telecommunicationsmust satisfy--needs can be extrapolated from currentbehavior.(2) The technological alternatives available--importantdevelopments are being made in transmission andswitching equipment and user terminals. (3) The effectiveness of thealternatives for meeting the needs--studies should combine the laboratoryand outside world and should focus on typical consumers aswell as business users.(4) The secondary effects--impact studies aredifficult and usually begin after the impact has been felt. Animpact study approach can be to ask what constraints would beloosened by the presence of a technological development. For example, lower costtelecommunications would remove one constraint on longdistance calls and could lead to new group associations.Several disciplines are relevant toresearch that is needed, including informationtheory, management studies, psychology, sociology, urban and regionalplanning and geogTaphy. (MG) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

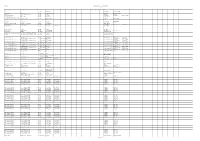

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Scotland's Home of News and Entertainment

Scotland’s home of news and entertainment Strategy Update May 2018 STV in 2020 • A truly multi-platform media company with a balanced profit base across broadcast, production and digital o Expect around 1/3rd of profit from sources other than linear spot advertising (vs 17% today) • A magnet for the best creative talent from Scotland and beyond • A brand famous for a range of high quality programming and accessible by all Scots wherever they are in the world via the STV app • One of the UK’s leading producers, making world class returning series for a range of domestic and international players • Working in partnership with creative talent, advertisers, businesses and Government to drive the Scottish economy and showcase Scotland to the world Scotland’s home of news and entertainment 2 We have a number of strengths and areas of competitive advantage Strong, trusted brand Unrivalled Talented, connection with committed people Scottish viewers and advertisers Robust balance sheet and growing Scotland’s most returns to powerful marketing shareholders platform Settled A production relationship with business well ITV which placed for incentivises STV Profitable, growing “nations and to go digital digital business regions” growth holding valuable data 3 However, there is also significant potential for improvement •STV not famous for enough new programming beyond news •STV brand perceived as ageing and safe BROADCAST •STV2 not cutting through •News very broadcast-centric and does not embrace digital •STV Player user experience lags competition -

Tribeca Film in Partnership with American Express Presents with Film 4, UK Film Council, Scottish Screen and Wild Bunch a Bluel

Tribeca Film in Partnership with American Express presents with Film 4, UK Film Council, Scottish Screen and Wild Bunch a blueLight, Fidelite Films, Studio Urania production NEDS Winner – Best Film, Evening Standard British Film Awards Winner – Golden Shell for Best Film, San Sebastian Film Festival Winner – Silver Shell for Best Actor, Conor McCarron San Sebastian Film Festival Winner- Young British Performer of the Year, Conor McCarron London Film Critics’ Circle Awards US Premiere Tribeca Film Festival 2011 Available on VOD Nationwide: April 20-June 23, 2011 May 13, 2011- Los Angeles June 17, 2011 – Miami Available August 23 on DVD PRESS CONTACTS Distributor: Publicity: ID PR Tammie Rosen Dani Weinstein Tribeca Film Sara Serlen 212-941-2003 Sheri Goldberg [email protected] 212-334-0333 375 Greenwich Street [email protected] New York, NY 10013 150 West 30th Street, 19th Floor New York, NY 10001 1 SYNOPSIS “If you want a NED, I‟ll give you a fucking NED!” Directed by the acclaimed actor/director Peter Mullan (MY NAME IS JOE, THE MAGDALENE SISTERS) NEDS, so called Non-Educated Delinquents, takes place in the gritty, savage and often violent world of 1970‟s Glasgow. On the brink of adolescence, young John McGill is a bright and sensitive boy, eager to learn and full of promise. But, the cards are stacked against him. Most of the adults in his life fail him in one way or another. His father is a drunken violent bully and his teachers – punishing John for the „sins‟ of his older brother, Benny – are down on him from the start. -

Mojave Desert Land Trust 2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT MOJAVE DESERT LAND TRUST ABOUT MDLT MISSION: The Mojave Desert Land Trust protects the Mojave Desert ecosystem and its natural, scenic, and cultural resource values. VISION: Dark night skies, clean air and water, broad views and vistas, and an abundance of native plants and animals. Photo: Lucas Basulto/MDLT The Mojave Desert Land Trust (MDLT) protects the unique living landscapes of the California deserts. Our service area spans nearly 26 million acres - the entire California portion of the Mojave and Colorado deserts - about 25% of the state. Since 2006 we have secured permanent and lasting protection for over 90,000 acres across the California deserts. We envisage the California desert as a vital ecosystem of interconnected, permanently protected scenic and natural areas that host a diversity of native plants and wildlife. Views and vistas are broad. The air is clear, the water clean, and the night skies dark. Cities and military facilities are compact and separated by large natural areas. Residents, visitors, land managers, and political leaders value the unique environment in which they live and work, as well as the impacts of global climate change upon the desert ecosystem. MDLT shares our mission of protecting wildlife corridors, land conservation education, habitat management and restoration, research, and outreach with the general public so they too can become well informed and passionate protectors and stewards of our desert resources. Only through acquisition, stewardship, public awareness, and advocacy can -

DESIGN DISCOURSE Composing and Revising Programs in Professional and Technical Writing

DESIGN DISCOURSE Composing and Revising Programs in Professional and Technical Writing Edited by David Franke Alex Reid Anthony DiRenzo DESIGN DISCOURSE: COMPOSING AND REVISING PROGRAMS IN PROFESSIONAL AND TECHNICAL WRITING PERSPECTIVES ON WRITING Series Editor, Mike Palmquist The Perspectives on Writing series addresses writing studies in a broad sense. Consistent with the wide ranging approaches characteristic of teaching and scholarship in writing across the curriculum, the series presents works that take divergent perspectives on working as a writer, teaching writing, administering writing programs, and studying writing in its various forms. The WAC Clearinghouse and Parlor Press are collaborating so that these books will be widely available through free digital distribution and low-cost print editions. The publishers and the Series editor are teachers and researchers of writing, committed to the principle that knowledge should freely circulate. We see the opportunities that new technologies have for further democratizing knowledge. And we see that to share the power of writing is to share the means for all to articulate their needs, interest, and learning into the great experiment of literacy. Other Books in the Series Charles Bazerman and David R. Russell, Writing Selves/Writing Societies (2003) Gerald P. Delahunty and James Garvey, The English Language: from Sound to Sense (2010) Charles Bazerman, Adair Bonini, and Débora Figueiredo (Eds.), Genre in a Changing World (2009) DESIGN DISCOURSE: COMPOSING AND REVISING PROGRAMS IN PROFESSIONAL AND TECHNICAL WRITING Edited by David Franke Alex Reid Anthony Di Renzo The WAC Clearinghouse wac.colostate.edu Fort Collins, Colorado Parlor Press www.parlorpress.com Anderson, South Carolina The WAC Clearinghouse, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 Parlor Press, 3015 Brackenberry Drive, Anderson, South Carolina 29621 © 2010 David Franke, Alex Reid, and Anthony Di Renzo. -

KREVISS Cargo Records Thanks WW DISCORDER and All Our Retail Accounts Across the Greater Vancouver Area

FLAMING LIPS DOWN BY LWN GIRL TROUBLE BOMB ATOMIC 61 KREVISS Cargo Records thanks WW DISCORDER and all our retail accounts across the greater Vancouver area. 1992 was a good year but you wouldn't dare start 1993 without having heard: JESUS LIZARD g| SEBADOH Liar Smash Your Head IJESUS LIZARD CS/CD On The Punk Rock CS/CD On Sebadoh's songwriter Lou Barlow:"... (his) songwriting sticks to your gullet like Delve into some raw cookie dough, uncharted musical and if he ever territory. overcomes his fascination with the The holiday season sound of his own being the perfect nonsense, his time for this baby Sebadoh could be from Jesus Lizard! the next greatest band on this Hallelujah! planet". -- Spin ROCKET FROM THE CRYPT Circa: Now! CS/CD/LP San Diego's saviour of Rock'n'Roll. Forthe ones who Riff-driven monster prefer the Grinch tunes that are to Santa Claus. catchier than the common cold and The most brutal, loud enough to turn unsympathetic and your speakers into a sickeningly repulsive smoldering heap of band ever. wood and wires. A must! Wl Other titles from these fine labels fjWMMgtlllli (roue/a-GO/ are available through JANUARY 1993 "I have a responsibility to young people. They're OFFICE USE ONLY the ones who helped me get where I am today!" ISSUE #120 - Erik Estrada, former CHiPs star, now celebrity monster truck commentator and Anthony Robbins supporter. IRREGULARS REGULARS A RETROSPECT ON 1992 AIRHEAD 4 BOMB vs. THE FLAMING LIPS COWSHEAD 5 SHINDIG 9 GIRL TROUBLE SUBTEXT 11 You Don't Go To Hilltop, You VIDEOPHILTER 21 7" T\ REAL LIVE ACTION 25 MOFO'S PSYCHOSONIC PIX 26 UNDER REVIEW 26 SPINLIST. -

2018 - Straini DACIN SARA

Repartitie aferenta trimestrului IV - 2018 - straini DACIN SARA TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Greg Pruss - Gregory Pruss 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.001 episode 1 2008 US Thom Beers Will Raee Philip David Segal Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.002 episode 2 2008 US Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.003 episode 3 2008 US Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.004 episode 4 2008 US Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.005 episode 5 2008 US Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.006 episode 6 2008 US Tom McMahon Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.007 episode 7 2008 US Tom McMahon Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.008 episode 8 2008 US Tom McMahon Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.009 episode 9 2008 US Thom Beers Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.010 episode 10 2008 US Thom Beers Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season 1, sez.01, ep.011 episode 11 2008 US Tom McMahon Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - 1000 ways to die - season -

ARMISTICE DAY No.5 DEADLINE Friday 31St June 2001

ARMISTICE DAY No.5 DEADLINE Friday 31st June 2001 ARMISTICE DAY 5 A Diplomacy zine from Stephen Agar, 47 Preston Drove, BRIGHTON, BN1 6LA. Tel: 01273-562430. Fax: 01273-706139. Email: [email protected] EDITORIAL own terms, and if they met them (more or less) I’d take I’m afraid that this issue is a little thin. I’m off to the job – and if they didn’t I would say no. I was Sorrento for a Postal Economics conference in a couple gambling that they wouldn’t want to change their mind of days, so I am just going to have to print the zine as it for the sake of a few thousand pounds. Anyway, after a is – no matter how short. It’s either that or delay things protracted haggle over pay and conditions, I ended up another week, which isn’t what I want to do. Part of the taking the job and I start at the beginning of July. So problem is that I never seem to get all the orders in until instead of putting together legal advice I have to come 4-5 days after the deadline! Now, this is a bit of a pain in up with a competitive strategy for UK letters as we enter the ass, especially when I’m trying to be a relatively the brave new world of Regulation and Competition. efficient editor. Therefore, I am introducing three How different this will be from providing the legal input changes: (1) all players with email will get a deadline into strategy remains to be seen – but at least instead of reminder two days before the deadline, (2) I’ll move the criticising the silly decisions of others I know get to deadline to Saturday and (3) I probably won’t wait if make some silly decisions of my very own. -

Official Report, Hutchesons’ Hospital Transfer and Corry to Speak

Meeting of the Parliament Thursday 25 April 2019 Session 5 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Thursday 25 April 2019 CONTENTS Col. GENERAL QUESTION TIME .................................................................................................................................. 1 Ferries Resilience Fund ................................................................................................................................ 1 Falkirk District Growth Deal .......................................................................................................................... 3 Air Traffic Incident (Kirkwall Airport) ............................................................................................................. 4 Endometriosis ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Hospital-acquired Infections ......................................................................................................................... 6 Northern Isles Ferries (Freight Capacity) ..................................................................................................... 8 FIRST MINISTER’S QUESTION TIME ................................................................................................................... 10 Education (Subject -

That Affair Next Door

That Affair Next Door By Anna Katharine Green THAT AFFAIR NEXT DOOR BOOK I MISS BUTTERWORTH'S WINDOW I A DISCOVERY I am not an inquisitive woman, but when, in the middle of a certain warm night in September, I heard a carriage draw up at the adjoining house and stop, I could not resist the temptation of leaving my bed and taking a peep through the curtains of my window. First: because the house was empty, or supposed to be so, the family still being, as I had every reason to believe, in Europe; and secondly: because, not being inquisitive, I often miss in my lonely and single life much that it would be both interesting and profitable for me to know. Luckily I made no such mistake this evening. I rose and looked out, and though I was far from realizing it at the time, took, by so doing, my first step in a course of inquiry which has ended—— But it is too soon to speak of the end. Rather let me tell you what I saw when I parted the curtains of my window in Gramercy Park, on the night of September 17, 1895. Not much at first glance, only a common hack drawn up at the neighboring curb-stone. The lamp which is supposed to light our part of the block is some rods away on the opposite side of the street, so that I obtained but a shadowy glimpse of a young man and woman standing below me on the pavement. I could see, however, that the woman—and not the man—was putting money into the driver's hand. -

A DESPERATE CHARACTER, and OTHER STORIES by Ivan Turgenev Translated from the Russian by Constance Garnett

A DESPERATE CHARACTER, AND OTHER STORIES By Ivan Turgenev Translated from the Russian By Constance Garnett 1899 TO JOSEPH CONRAD WHOSE ART IN ESSENCE OFTEN RECALLS THE ART AND ESSENCE OF TURGENEV INTRODUCTION The six tales now translated for the English reader were written by Turgenev at various dates between 1847 and 1881. Their chronological order is:— Pyetushkov, 1847 The Brigadier, 1867 A Strange Story, 1869 Punin and Baburin, 1874 Old Portraits, 1881 A Desperate Character, 1881 Pyetushkov is the work of a young man of twenty-nine, and its lively, unstrained realism is so bold, intimate, and delicate as to contradict the flattering compliment that the French have paid to one another—that Turgenev had need to dress his art by the aid of French mirrors. Although Pyetushkov shows us, by a certain open naïveté of style, that a youthful hand is at work, it is the hand of a young master, carrying out the realism of the ‘forties’—that of Gogol, Balzac, and Dickens— straightway, with finer point, to find a perfect equilibrium free from any bias or caricature. The whole strength and essence of the realistic method has been developed in Pyetushkov to its just limits. The Russians are instinctive realists, and carry the warmth of life into their pages, which warmth the French seem to lose in clarifying their impressions and crystallising them in art. Pyetushkov is not exquisite: it is irresistible. Note how the reader is transported bodily into Pyetushkov’s stuffy room, and how the major fairly boils out of the two pages he lives in! (pp.