Sleep-Wake Disturbances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENO Directory Over 20 Years Ago We Pioneered the Hammock Counter-Culture

ENO Directory Over 20 years ago we pioneered the hammock counter-culture. Environmental Conservation As a hammock company, we know the importance of trees and so do our customers. Since then, we’ve ventured We believe that when given the chance, individuals will use their purchasing power from mountains to sea, to protect the planet, which is why we plant two trees in an area of need for every hammock sold. Additionally, we proudly pledge 1% of our annual sales to support from backyard to backcountry, nonprofit organisations focused on environmental solutions. and everywhere in between. — MEMBER — No matter your passion or pursuit, our tried-and-true products outfit Materials & Chemistry you with an all-access pass to We are committed to the journey of building more sustainable and responsibly made explore, connect and relax... products. This includes sourcing high-quality materials with post-consumer recycled content and bluesign® approved chemistry, as well as adopting safer ingredients for water repellents, colour dyes, and beyond. We have adopted the industry leading bluesign® Restricted Substances List (RSL) which provides a comprehensive system for managing chemical hazards, workplace safety, and environmental impacts during material production. To support our RSL, we have set up a testing program with an accredited third-party laboratory and have placed an emphasis on priority chemicals of concern established by the outdoor industry. We look forward to sharing our progress along the way. Hammocks 3 - 6 Social Responsibility We protect the welfare of our community and the planet from the beginning to the end Specialist Hammocks 7 - 9 of our product life cycle through a strict code of conduct, product repair and take- back programs. -

View Catalog

RELAXATION REDEFINED 2 THE HAMMOCK SOURCE HAMMOCKSOURCE.COM 3 4 THE HAMMOCK SOURCE TABLE OF #1 Brand Name CONTENTS 6 ......... Pawleys Island Rope Hammocks in the industry 8 ......... Pawleys Island Soft Weave Hammocks 10 ....... Pawleys Island Quilted Hammocks 12 ....... Pawleys Island Poolside Hammocks 14 ....... Pawleys Island Swings 16 ....... Pawleys Island Coastal Collection 130 year old tradition 18 ....... Pawleys Island Hammock Pillows 20 ....... Pawleys Island Decorative Pillows 24 ....... Pawleys Island Refined Collection of Quality & Style 28 ....... Pawleys Island Comfort Collection 32 ....... Pawleys Island Essentials Collection 36 ....... Pawleys Island Sunrise Collection 40 ....... Pawleys Island Crescent Collection 44 ....... Pawleys Island Terrace Collection 48 ....... Pawleys Island Adirondack Chairs Handcrafted one at a 50 ....... Pawleys Island Dining Collection 52 ....... Pawleys Island High Dining Collection 54 ....... Pawleys Island Dining Tables time in the Carolinas 56 ....... Pawleys Island Counter Height Collection 56 ....... Pawleys Island Rocker Collection 58 ....... Pawleys Island Swings, Gliders & Benches 58 ....... Pawleys Island Accessories 60 ....... Pawleys Island Swatches 64 ....... Pawleys Island Hammock & Swing Stands Time-honored 64 ....... Pawleys Island Hammock Accessories 68 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Tufted Hammocks craftsmanship using 70 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Pillowtop Hammocks 72 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Quilted Hammocks 74 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Soft Weave Hammocks the latest materials 76 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Rope Hammocks 78 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Tufted Single Swings 80 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Deluxe Double Swing 84 ....... Hatteras Hammocks & Swing Stands 84 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Accessories 86 ....... Hatteras Hammocks Pillows THE ORIGINAL PAWLEYS ISLAND 5 ROPE HAMMOCKS 6 THE HAMMOCK SOURCE Relax in a century old tradition. Our well-crafted rope hammock is a net for your body with holes just wide enough for your worries to fall through. -

Jungle Kit List

Jungle Kit List Here is a suggested Kit List. Most is essential for a comfortable trip. Some additional notes are below regarding the starred items. Equipment Books (kindle is effective) Hammock* Gardening gloves (big thorns in Jungle) Thin sleeping bag/ sleeping bag liner* Water bottles- min 2L volume in total Thermarest* Mess tin Wash kit Plate Quick drying travel towel Cup (metal one) Travel pillow- for plane & hammock Spork Waterproof stuff sacks for clothes Tarpaulin for shelter* Clothes Knife* Gaffa tape Socks Paracord approx. 3m Shoes* Bandana/ buff T shirts (Exile will provide x2) Thin waterproof Jacket and trousers Long sleeve t shirts Insect repellent 50% DEET Jumper x 1 Camera (batteries/ memory/ Shorts waterproof case) Long trousers x2 (one into shorts is Suncream handy) Aftersun Swimming stuff Watch Sun hat Spare torch Sunglasses Headtorch (suggest Petzl Tikka) Shoes* Notebook Permanent marker Medical Whistle iPod & headphones Stethoscope Wetwipes Pen torch Earplugs Anti malarials* Personal medical kit – compeed, cotton buds, simple analgesia, hand anti-bac gel, dioralyte, Food In the forest, there is no reliable means of keeping food cool. Cooking facilities are limited to boiling food up in hot water, or adding hot water to dehydrated meals. No cooking pots are provided in which to cook, though mess tins work well. Expedition meals, such as Wayfarer are convenient and tasty. Otherwise head over to the exile medics website to place an order for some (personal recommendations include the curry and porridge with maple syrup….) For breakfast, some eat porridge type stuff, many of us Just have cereal bars. Lunch is whatever you can find. -

Specialised Camping Hammocks & Tarps

Specialised Camping Hammocks & Tarps CONTENTS About DD Hammocks . .3 Product Range. .4 DD Hammocks. 5 All Hammocks. .6 Hammock Accessories & Suspension. .13 Mosquito Nets. 16 DD Tarps. .18 All Tarps. .19 Tarp Suspension & Accessories. .25 DD Superlight Range. .26 Superlight Suspension & Accessories. 32 DD Multicam Range . .33 DD Superlight Tents . .36 Ultralight Hammock Stand. 44 Camping Accessories. 46 Insulation. .52 Clothing. .58 Share Your Experience. 60 2 ABOUT DD HAMMOCKS DD have been at the forefront of hammock camping since 2005. Our current range of exciting and innovative products are the result of many years of prototype building, testing in different environments and long periods of development, combined with some great feedback and suggestions we’ve received from many people along the way. We have an extensive knowledge of hammock camping in some very harsh environments and our products are built to withstand the worst nature can throw at them. We believe innovation of products should be ongoing and we continue to spend many hours working on existing products as well as new and exiting ideas. Some of the products we have developed over the years include a hammock / bivi (sleep on the ground or hang from the trees!); a high spec fully modular hammock; hammock specific sleeping bags; very versatile tarps and the lightest hammock in the world! We are a small friendly team based in Edinburgh in the UK and we sell our products worldwide. Our range includes products suitable for hot, cold, windy, wet and extreme environments all over the world. Our products are used by some of the leading bushcraft schools, jungle training organisations, on TV survival shows and by people like you and us. -

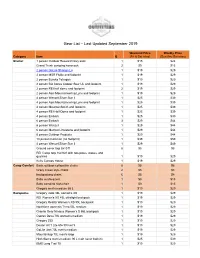

Gear List 09-2019

Gear List – Last Updated September 2019 Weekend Price Weekly Price Category Item Q (Fri & Sat nites) (Sun thru Sat nites) Shelter 1 person Outdoor Research bivy sack 1 $15 $24 Grand Trunk campinG hammock 2 $9 $15 2 person GoLite ShanGri-La 1 $19 $29 2 person MSR Flylite and footprint 1 $19 $29 2 person Eureka TetraGon 1 $19 $29 2 person BiG AGnes Copper Spur UL and footprint 1 $19 $29 2 person REI half dome and footprint 2 $19 $29 2 person Alps MountaineerinG Lynx and footprint 1 $19 $29 4 person Wenzel Silver Star II 1 $25 $39 4 person Alps MountaineerinG Lynx and footprint 1 $25 $39 4 person MountainSmith and footprint 1 $25 $39 4 person REI Half Dome and footprint 1 $25 $39 4 person Embark 1 $25 $39 6 person Embark 3 $29 $44 6 person Wenzel 1 $29 $44 6 person Marmot Limestone and footprint 1 $29 $44 6 person Outdoor Products 1 $29 $44 10 person Coleman (no footprint) 1 $39 $59 4 person Wenzel Silver Star II 1 $29 $49 Ground cover tarp 8x10 ft 8 $5 $8 REI Camp tarp 16x16 ft with two poles, stakes, and Guylines 1 $19 $29 Kelty Canopy House 1 $19 $29 Camp Comfort Basic outdoor collapsible chairs 8 $5 $8 Crazy Creek style chairs 2 $5 $8 backpackinG chairs 6 $5 $8 Baby sun/buG tent 1 $9 $15 Baby campinG hiGh-chair 1 $9 $15 GreGory men's medium 65 L 1 $19 $29 Backpacks GreGory Jade 38L women's XS 1 $19 $29 REI Women's XS 45L ultraliGht backpack 1 $19 $29 GreGory Reality Women's XS 55L backpack 1 $19 $29 Northface women's Terra 55L medium 1 $19 $29 Granite Gear Nimbus Women's S 55L backpack 1 $19 $29 Osprey Deva 70L women's medium 1 $19 $29 -

Development and Evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS) Franklin Christian Brown

Louisiana Tech University Louisiana Tech Digital Commons Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School Fall 2002 Development and evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS) Franklin Christian Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.latech.edu/dissertations Part of the Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy Commons INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Development And Evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS) Franklin C. Brown, M.A. College of Education Louisiana Tech University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy November 2002 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Expert Tips and Picks for Comfortable Hammock Camping

https://boyslife.org/outdoors/guygear/167003/hammock- camping/?utm_source=scoutingwire&utm_campaign=swvolunteer2262020&utm_medium=email&utm_ content= Expert Tips and Picks for Comfortable Hammock Camping By Michael Lanza Hammock camping looks so fun, right? It can be a comfortable alternative to tent camping for backpacking and drive-in campgrounds. If you’re going to try it, do it right with these expert tips and picks for the best gear. PROS AND CONS OF HAMMOCK CAMPING For starters, understand the pros and cons of hammock camping. PROS: • If you like being suspended in the air, hammock camping offers super comfort. • Whether rocky, uneven, muddy or wet, the ground doesn’t matter. • Done right, sleeping in a hammock can be warm, dry and quiet. • You get a great view of the stars on a clear night. CONS: • Stringing up a hammock requires a pair of sturdy trees an appropriate distance apart, whose trunks are not blocked by thick boughs. This is not easy or possible in all environments. • A hammock slopes toward the middle in a banana shape, which some people find uncomfortable — especially those who shift a lot in their sleep. • Your bed sways with every slight movement, which isn’t appealing to everyone. • In sustained rain, a hammock doesn’t offer shelter for two or more people to stay dry together in camp, and it offers little space for one person to move around if sheltering for hours from rain. Try sleeping in a hammock in your yard before buying all the gear and making plans to hammock camp on a backpacking trip. -

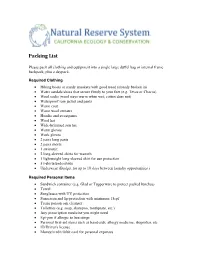

Packing List

Packing List Please pack all clothing and equipment into a single large duffel bag or internal frame backpack, plus a daypack. Required Clothing • Hiking boots or sturdy sneakers with good tread (already broken in) • Water sandals/shoes that secure firmly to your feet (e.g. Tevas or Chacos) • Wool socks (wool stays warm when wet; cotton does not) • Waterproof rain jacket and pants • Warm coat • Warm wool sweater • Hoodie and sweatpants • Wool hat • Wide-brimmed sun hat • Warm gloves • Work gloves • 2 pairs long pants • 2 pairs shorts • 1 swimsuit • 2 long-sleeved shirts for warmth • 1 lightweight long-sleeved shirt for sun protection • 5 t-shirts/undershirts • Underwear (Budget for up to 10 days between laundry opportunities.) Required Personal Items • Sandwich container (e.g. Glad or Tupperware to protect packed lunches) • Towel • Sunglasses with UV protection • Sunscreen and lip protection with minimum 15spf • Tecnu poison oak cleanser • Toiletries (e.g. soap, shampoo, toothpaste, etc.) • Any prescription medicine you might need • Epi-pen if allergic to bee stings • Personal first-aid items such as band-aids, allergy medicine, ibuprofen, etc. • ID/Driver's license • Money/credit/debit card for personal expenses Required Equipment • Laptop computer with wireless connectivity, sufficient battery life, MS Office, and JMP Statistical Software (JMP is available through your home campus, you must have it loaded and tested for functionality before arrival to the course) • Small tent (1-2 person) with durable rainfly and footprint tarp • Warm sleeping bag (Temperatures may dip below freezing: if your sleeping bag is not rated at 20° F or colder, you will need to bring a sleeping bag liner as well.) • Packable inflatable sleeping pad (e.g. -

Blue Ridge Camping Hammock

Lawson Hammock BLUE RIDGE CAMPING HAMMOCK These parts are inside your stuff sack, ready to assemble: H A M M O C K W / C O L L A P S E D S P R E A D E R B A R S 1 At each end of the unrolled hammock, join spreader bar halves. Make sure ropes aren’t tangled around bar. Can cause breakage. Check all knots on ropes attached to hammock bed for tightness. A R C H P O L E S R A I N F L Y / T A R P Ropes may stretch with use, requiring occasional re-tightening. B T Y I N G A B O W L I N E A 2 Hang hammock between two trees or sturdy upright objects using 3 Once hammock is hung, fit together the two shock-corded aluminum Suspension Straps (Recommended & Sold on our website), other arch poles and slide one through each sleeve on top of hammock. straps or rope/webbing (as shown). If using rope, attach to Insert end of each pole through grommet as shown (detail A). Attach hammock end loop (blue paracord) with a bowline or other strong snap hooks on elastic cords at ends of hammock to tops of arch knot, and wrap rope at least once around tree before re-attaching poles (detail B). Shorten elastic if necessary to keep canopy tight. to hammock end loop with another bowline (see detail above). NOTE: Tie 3–4’ off ground, keeping rope & hammock taut. A BIVY SETUP: Follow above instructions, but do not hang (#2). -

University of Kentucky Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 25Th Annual PM&R Research

University of Kentucky Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 25th Annual PM&R Research Day Cardinal Hill Rehabilitation Hospital Center of Learning Lexington, Kentucky May 23, 2013 PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 25th Annual Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Research Day May 23, 2013 Cardinal Hill Rehabilitation Hospital Lexington, KY 25th Annual Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Research Day May 23, 2013 Cardinal Hill Rehabilitation Hospital Lexington, KY Table of Contents Agenda…………….…………………………………….…..…3-5 Oral Presentations………………………………………..….6-30 Poster Presentations………………………………………..31-43 Notes…………………………………………………………….44 Speaker Profile/Abstract……………………………...………45 Speaker Presentation Handouts..………………………...46-67 2 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL MEDICINE & REHABILITATION 25th ANNUAL RESEARCH DAY AGENDA CARDINAL HILL REHABILITATION HOSPITAL CENTER OF LEARNING May 23, 2013 7:00 a.m. – 7:50 a.m. Dr. Cohen breakfast Lecture and Roundtable with Residents (Cardinal Hill Boardroom) 7:50 a.m. – 8:00 a.m. Opening Remarks (CL3): Gerald Klim, DO PM&R RESIDENT RESEARCH PRESENTATIONS – CL3 8:00 a.m. – 8:15 a.m. Aaron Lyles, MD, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation “Acute Rehabilitation of Patient with Surgically Acquired Central Alveolar Hypoventilation Syndrome” 8:15 a.m. – 8:30 a.m. Zhangliang Ma, MD, PhD, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation “Study on Active HCMV Infection in Left MCA Stroke Patients” 8:30 a.m. – 8:45 a.m. Kavita Manchikanti, MD, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation “Post Traumatic Headaches: A Description and Comparison of Headache Patterns in Traumatic Brain Injury and Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder” 8:45 a.m. – 9:00 a.m. Praveen N. Pakeerappa, MD, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation “Botulinum Toxin A Injection to Facial Muscles in Patient with Stiff Person Syndrome Implanted with Baclofen Pump: A Case Report” 9:00 a.m. -

View PDF Version

RSC Advances REVIEW View Article Online View Journal | View Issue Cytochrome P450 1B1: role in health and disease and effect of nutrition on its expression Cite this: RSC Adv.,2019,9,21050 Bakht Ramin Shah, *a Wei Xu b and Jan Mraza This review summarizes the available literature stating CYP1B1 to provide the readers with a comprehensive understanding of its role in different diseases, as well as the importance of nutrition in their control in terms of the influence of different nutrients on its expression. CYP1B1, a member of the cytochrome P450 enzyme family is expressed in different human tissues and is known to contribute to different life alarming pathologies. Particularly, till now much attention has been paid to its involvement in the development of primary congenital glaucoma (PCG) and cancer. However, recently there are some reports highlighting CYP1B1 as a potential regulator in energy homeostasis and adipogenesis thus promoting obesity and hypertension as well. Therefore, seeking out effective strategies to modulate the expression of CYP1B1 is a challenging task. In this context, nutrients based strategies will be the best choice as they are mostly Received 16th May 2019 harmless and are easily available in one's diet. In conclusion, this article will be helpful in providing a base Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. Accepted 23rd June 2019 for further research that is needed to identify the role of CYP1B1 in progression of different diseases, DOI: 10.1039/c9ra03674a hypertension and obesity in particular, and then to present the effectiveness, mechanisms, and biologic rsc.li/rsc-advances plausibility of nutrients against its expression. -

TRAVEL BROCHURE Nature’S Sway® - Organic Nature’S Sway Baby Hammock Is an Alter- Native to a Moses Basket Or Bassinet

BABY BOOGIEWOOGIE TRAVEL BROCHURE Nature’s Sway® - Organic Nature’s Sway baby hammock is an alter- native to a Moses basket or bassinet. The hammock imitates the embrace of the parents’ arms making the baby feel safe, while the rhythmic movements like rock- ing, swaying and bouncing have a calming effect that are well known to help babies fall asleep peacefully. The baby hammock is also practical and easy to move around. With the door frame clamp you can keep your baby nearby you at all times. Please note: When a child is able to roll, sit, kneel or to pull themselves up, the hammock is no longer safe and should not be used. RENT IT Stroller Metro+, Ergobaby The Metro+ from awordwinning Ergoba- by provides extra cushy padding and an adjustable handlebar, providing ultimate comfort and support for both baby and parents ––tall and small. Super easy to handle with ultra-compact fold. Perfe- ct for napping with the 175 degree seat recline. Newborn suitable with nest flaps that keeps the baby cozy and secure. From newborn to 22 kg (4 years). RENT IT Organic Babynest, Filibabba The babynest is produced in 100% ultra soft organic cotton. The babynest provides a safe space for the baby to sleep or play. It can be opened at the foot end by clicking the leather belt off, which gives a longer lying measure to the growing baby who still needs to feel enclo- sed. It is also possible to zip the edge off and use it as a smaller bedbumper in the cot.