Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Orchid Society South Australia

Journal of the Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc PRINT POST APPROVED VOLUME 25 NO. 11 PP 54366200018 DECEMBER 2001 NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA POST OFFICE BOX 565 UNLEY SOUTH AUSTRALIA 5061 The Native Orchid Society of South Australia promotes the conservation of orchids through the preservation of natural habitat and through cultivation. Except with the documented official representation from the Management Committee no person is authorised to represent the society on any matter. All native orchids are protected plants in the wild. Their collection without written Government permit is illegal. PRESIDENT: SECRETARY: Bill Dear Cathy Houston Telephone: 82962111 Telephone: 8356 7356 VICE-PRESIDENT David Pettifor Tel. 014095457 COMMITTEE David Hirst Thelma Bridle Bob Bates Malcolm Guy EDITOR: TREASURER Gerry Carne Iris Freeman 118 Hewitt Avenue Toorak Gardens SA 5061 Telephone/Fax 8332 7730 E-mail [email protected] LIFE MEMBERS Mr R. Hargreaves Mr G. Carne Mr L. Nesbitt Mr R. Bates Mr R. Robjohns Mr R Shooter Mr D. Wells Registrar of Judges: Reg Shooter Trading Table: Judy Penney Field Trips & Conservation: Thelma Bridle Tel. 83844174 Tuber Bank Coordinator: Malcolm Guy Tel. 82767350 New Members Coordinator David Pettifor Tel. 0416 095 095 PATRON: Mr T.R.N. Lothian The Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc. while taking all due care, take no responsibility for the loss, destruction or damage to any plants whether at shows, meetings or exhibits. Views or opinions expressed by authors of articles within this Journal do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Management. We condones the reprint of any articles if acknowledgement is given. -

Native Orchid Society of South Australia

NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY of SOUTH AUSTRALIA NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA JOURNAL Volume 6, No. 10, November, 1982 Registered by Australia Post Publication No. SBH 1344. Price 40c PATRON: Mr T.R.N. Lothian PRESIDENT: Mr J.T. Simmons SECRETARY: Mr E.R. Hargreaves 4 Gothic Avenue 1 Halmon Avenue STONYFELL S.A. 5066 EVERARD PARK SA 5035 Telephone 32 5070 Telephone 293 2471 297 3724 VICE-PRESIDENT: Mr G.J. Nieuwenhoven COMMITTFE: Mr R. Shooter Mr P. Barnes TREASURER: Mr R.T. Robjohns Mrs A. Howe Mr R. Markwick EDITOR: Mr G.J. Nieuwenhoven NEXT MEETING WHEN: Tuesday, 23rd November, 1982 at 8.00 p.m. WHERE St. Matthews Hail, Bridge Street, Kensington. SUBJECT: This is our final meeting for 1982 and will take the form of a Social Evening. We will be showing a few slides to start the evening. Each member is requested to bring a plate. Tea, coffee, etc. will be provided. Plant Display and Commentary as usual, and Christmas raffle. NEW MEMBERS Mr. L. Field Mr. R.N. Pederson Mr. D. Unsworth Mrs. P.A. Biddiss Would all members please return any outstanding library books at the next meeting. FIELD TRIP -- CHANGE OF DATE AND VENUE The Field Trip to Peters Creek scheduled for 27th November, 1982, and announced in the last Journal has been cancelled. The extended dry season has not been conducive to flowering of the rarer moisture- loving Microtis spp., which were to be the objective of the trip. 92 FIELD TRIP - CHANGE OF DATE AND VENUE (Continued) Instead, an alternative trip has been arranged for Saturday afternoon, 4th December, 1982, meeting in Mount Compass at 2.00 p.m. -

Australia Lacks Stem Succulents but Is It Depauperate in Plants With

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Australia lacks stem succulents but is it depauperate in plants with crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM)? 1,2 3 3 Joseph AM Holtum , Lillian P Hancock , Erika J Edwards , 4 5 6 Michael D Crisp , Darren M Crayn , Rowan Sage and 2 Klaus Winter In the flora of Australia, the driest vegetated continent, [1,2,3]. Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), a water- crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), the most water-use use efficient form of photosynthesis typically associated efficient form of photosynthesis, is documented in only 0.6% of with leaf and stem succulence, also appears poorly repre- native species. Most are epiphytes and only seven terrestrial. sented in Australia. If 6% of vascular plants worldwide However, much of Australia is unsurveyed, and carbon isotope exhibit CAM [4], Australia should host 1300 CAM signature, commonly used to assess photosynthetic pathway species [5]. At present CAM has been documented in diversity, does not distinguish between plants with low-levels of only 120 named species (Table 1). Most are epiphytes, a CAM and C3 plants. We provide the first census of CAM for the mere seven are terrestrial. Australian flora and suggest that the real frequency of CAM in the flora is double that currently known, with the number of Ellenberg [2] suggested that rainfall in arid Australia is too terrestrial CAM species probably 10-fold greater. Still unpredictable to support the massive water-storing suc- unresolved is the question why the large stem-succulent life — culent life-form found amongst cacti, agaves and form is absent from the native Australian flora even though euphorbs. -

Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society of London

I 3 2044 105 172"381 : JOURNAL OF THE llopl lortimltoal fbck EDITED BY Key. GEORGE HEXSLOW, ALA., E.L.S., F.G.S. rtanical Demonstrator, and Secretary to the Scientific Committee of the Royal Horticultural Society. VOLUME VI Gray Herbarium Harvard University LOXD N II. WEEDE & Co., PRINTERS, BEOMPTON. ' 1 8 8 0. HARVARD UNIVERSITY HERBARIUM. THE GIFT 0F f 4a Ziiau7- m 3 2044 i"05 172 38" J O U E N A L OF THE EDITED BY Eev. GEOEGE HENSLOW, M.A., F.L.S., F.G.S. Botanical Demonstrator, and Secretary to the Scientific Committee of the Royal Horticultural Society. YOLUME "VI. LONDON: H. WEEDE & Co., PRINTERS, BROMPTON, 1 8 80, OOUITOIL OF THE ROYAL HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY. 1 8 8 0. Patron. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN. President. The Eight Honourable Lord Aberdare. Vice- Presidents. Lord Alfred S. Churchill. Arthur Grote, Esq., F.L.S. Sir Trevor Lawrence, Bt., M.P. H. J". Elwes, Esq. Treasurer. Henry "W ebb, Esq., Secretary. Eobert Hogg, Esq., LL.D., F.L.S. Members of Council. G. T. Clarke, Esq. W. Haughton, Esq. Colonel R. Tretor Clarke. Major F. Mason. The Rev. H. Harpur Crewe. Sir Henry Scudamore J. Denny, Esq., M.D. Stanhope, Bart. Sir Charles "W. Strickland, Bart. Auditors. R. A. Aspinall, Esq. John Lee, Esq. James F. West, Esq. Assistant Secretary. Samuel Jennings, Esq., F.L S. Chief Clerk J. Douglas Dick. Bankers. London and County Bank, High Street, Kensington, W. Garden Superintendent. A. F. Barron. iv ROYAL HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY. SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE, 1880. Chairman. Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, K.C.S.I., M.D., C.B.,F.R.S., V.P.L.S., Royal Gardens, Kew. -

Lamington National Park Management Plan 2011

South East Queensland Bioregion Prepared by: Planning Services Unit Department of Environment and Resource Management © State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Resource Management) 2011 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Department of Environment and Resource Management. Enquiries should be addressed to Department of Environment and Resource Management, GPO Box 2454, Brisbane Qld 4001. Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. This management plan has been prepared in accordance with the Nature Conservation Act 1992. This management plan does not intend to affect, diminish or extinguish native title or associated rights. Note that implementing some management strategies might need to be phased in according to resource availability. For information on protected area management plans, visit <www.derm.qld.gov.au>. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3224 8412. This publication can be made available in alternative formats (including large print and audiotape) on request for people with a vision impairment. -

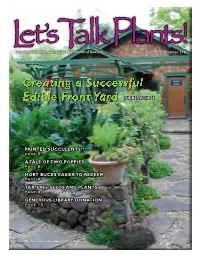

Creating a Successful Edible Front Yard See Page 1

LNewsletteret’s of the San DiegoT Horticulturalalk Society PlNovemberants! 2012, Number 218 Creating a Successful Edible Front Yard SEE PAGE 1 PAINTED SUCCULENTS??? page 5 A TALE OF TWO POPPIES page 6 HORT BUCKS EASIER TO REDEEM page 8 TAX-FREE SEEDS AND PLANTS page 9 GENEROUS LIBRARY DONATION page 12 On the Cover: An edible front yard November Featured Garden Date: November 25 Time: 10am to 2pm Location: Escondido Cathy Carey Cathy The next Featured Garden is at Cathy Carey's exciting garden and fascinating artist studio near Lake Hodges in Escondido. Learn about Cathy’s art at www.artstudiosandiego.com. Details will be emailed to members in your monthly eblast, and are also on our website, where you’ll be able to register: http://sdhort.org/FeaturedGarden ▼SDHS SPONSOR GREEN THUMB SUPER GARDEN CENTERS 1019 W. San Marcos Blvd. • 760-744-3822 (Off the 78 Frwy. near Via Vera Cruz) • CALIFORNIA NURSERY PROFESSIONALS ON STAFF • HOME OF THE NURSERY EXPERTS • GROWER DIRECT www.supergarden.com Now on Facebook WITH THIS VALUABLE Coupon $10 00 OFF Any Purchase of $6000 or More! • Must present printed coupon to cashier at time of purchase • Not valid with any sale items or with other coupons or offers • Offer does not include Sod, Gift Certifi cates, or Department 56 • Not valid with previous purchases • Limit 1 coupon per household • Coupon expires 11/30/2012 at 6 p.m. San Diego Horticultural Society In This Issue... Our Mission is to promote the enjoyment, art, knowledge 2 2013 Spring Garden Tour: Making Great Progress and public awareness of horticulture in the San Diego area, 2 Important Member Information while providing the opportunity for education and research. -

Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc

Native Orchid Society of South Australia Inc. Journal Diuris calcicola One of new orchid species named in 2015 Photo: R. Bates June 2016 Volume 40 No. 5 Native Orchid Society of South Australia June 2016 Vol. 40 No. 5 The Native Orchid Society of South Australia promotes the conservation of orchids through preservation of natural habitat and cultivation. Except with the documented official representation of the management committee, no person may represent the Society on any matter. All native President orchids are protected in the wild; their collection without written Vacant Government permit is illegal. Vice President Robert Lawrence Contents Email: [email protected] Title Author Page Secretary Bulletin Board 54 Rosalie Lawrence Vice President’s Report Robert Lawrence 55 Email:[email protected] May Field Trip – From a newbie Vicki Morris 56 Treasurer NOSSA Seed Kits 2016 Les Nesbitt 57 Christine Robertson The Orchid & Mycorrhiza Fungus… Rob Soergel 57 Email: [email protected] Editor Growing Exercise Recall Les Nesbitt 58 Lorraine Badger Diuris Project Report Les Nesbitt 58 Assistant Editor - Rob Soergel May Meeting Review Rob Soergel 58 Email: [email protected] Pterostylis - Reprint 59 Committee Letters to the editor 60 Michael Clark May Orchid Pictures Competition Rosalie Lawrence 62 Bob Bates April Benched Orchids Results Les Nesbitt 63 Kris Kopicki April Benched Orchids Photos Judy & Greg Sara 64 Other Positions Membership Liaison Officer Life Members Robert Lawrence Mr R Hargreaves† Mr G Carne Mrs T Bridle Ph: 8294 8014 Email:[email protected] Mr H Goldsack† Mr R Bates Botanical Advisor Mr R Robjohns† Mr R Shooter Bob Bates Mr J Simmons† Mr W Dear Conservation Officer Mr D Wells† Mrs C Houston Thelma Bridle Ph: 8384 4174 Mr L Nesbitt Mr D Hirst Field Trips Coordinator Michael Clark Patron: Mr L. -

Review Article Organic Compounds: Contents and Their Role in Improving Seed Germination and Protocorm Development in Orchids

Hindawi International Journal of Agronomy Volume 2020, Article ID 2795108, 12 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2795108 Review Article Organic Compounds: Contents and Their Role in Improving Seed Germination and Protocorm Development in Orchids Edy Setiti Wida Utami and Sucipto Hariyanto Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya 60115, Indonesia Correspondence should be addressed to Sucipto Hariyanto; [email protected] Received 26 January 2020; Revised 9 May 2020; Accepted 23 May 2020; Published 11 June 2020 Academic Editor: Isabel Marques Copyright © 2020 Edy Setiti Wida Utami and Sucipto Hariyanto. ,is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In nature, orchid seed germination is obligatory following infection by mycorrhizal fungi, which supplies the developing embryo with water, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals, causing the seeds to germinate relatively slowly and at a low germination rate. ,e nonsymbiotic germination of orchid seeds found in 1922 is applicable to in vitro propagation. ,e success of seed germination in vitro is influenced by supplementation with organic compounds. Here, we review the scientific literature in terms of the contents and role of organic supplements in promoting seed germination, protocorm development, and seedling growth in orchids. We systematically collected information from scientific literature databases including Scopus, Google Scholar, and ProQuest, as well as published books and conference proceedings. Various organic compounds, i.e., coconut water (CW), peptone (P), banana homogenate (BH), potato homogenate (PH), chitosan (CHT), tomato juice (TJ), and yeast extract (YE), can promote seed germination and growth and development of various orchids. -

Plant of the Week – Rhizanthella Slateri

One of the World’s Rarest Orchids Rhizanthella slateri The Eastern Australian Underground Orchid The genus Rhizanthella are extremely unusual orchids, only found in Australia. They spend all their lives underground, only emerging when they flower. Even then, the flowers are usually hidden by soil or leaf litter. Consequently, they are very hard to find, are all critically endangered, and are often listed in the top 10 rarest orchids in the world. There are currently five species known. Rhizanthella gardneri and R. johnstonii are found in the south-west of Western Australia, where they occur under Broombush (Melaleuca sp.). The underground orchids from eastern Australia are even rarer; so rare that they often don’t even make it onto lists of rare orchids! Rhizanthella omissa is known from a single collection in south-eastern Queensland; and a newly described species, R. speciosa, is known from a single location in Barrington Tops National Park. Figure: Two composite flowering heads from the recently discovered Lane Cove population of Rhizanthella slateri. Note the lack of chlorophyll and the yellow pollinia within the individual flowers The final species, Rhizanthella slateri, is known from a small number of plants at a handful of locations: near Buladelah; in the Watagan Mountains; in the Blue Mountains; and near Nowra. So that makes it even more remarkable that in 2020, a new population of R. slateri was found within five kilometers of the Macquarie Campus. The new population, consisting of 14 plants, was found in local bushland by Vanessa McPherson and Michael Gillings while they were surveying for club and coral fungi. -

Orchid Historical Biogeography, Diversification, Antarctica and The

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) ORIGINAL Orchid historical biogeography, ARTICLE diversification, Antarctica and the paradox of orchid dispersal Thomas J. Givnish1*, Daniel Spalink1, Mercedes Ames1, Stephanie P. Lyon1, Steven J. Hunter1, Alejandro Zuluaga1,2, Alfonso Doucette1, Giovanny Giraldo Caro1, James McDaniel1, Mark A. Clements3, Mary T. K. Arroyo4, Lorena Endara5, Ricardo Kriebel1, Norris H. Williams5 and Kenneth M. Cameron1 1Department of Botany, University of ABSTRACT Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, Aim Orchidaceae is the most species-rich angiosperm family and has one of USA, 2Departamento de Biologıa, the broadest distributions. Until now, the lack of a well-resolved phylogeny has Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, 3Centre for Australian National Biodiversity prevented analyses of orchid historical biogeography. In this study, we use such Research, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia, a phylogeny to estimate the geographical spread of orchids, evaluate the impor- 4Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity, tance of different regions in their diversification and assess the role of long-dis- Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, tance dispersal (LDD) in generating orchid diversity. 5 Santiago, Chile, Department of Biology, Location Global. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Methods Analyses use a phylogeny including species representing all five orchid subfamilies and almost all tribes and subtribes, calibrated against 17 angiosperm fossils. We estimated historical biogeography and assessed the -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 503 the Vascular Plants Of

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 503 THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF MAJURO ATOLL, REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS BY NANCY VANDER VELDE ISSUED BY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON, D.C., U.S.A. AUGUST 2003 Uliga Figure 1. Majuro Atoll THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF MAJURO ATOLL, REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS ABSTRACT Majuro Atoll has been a center of activity for the Marshall Islands since 1944 and is now the major population center and port of entry for the country. Previous to the accompanying study, no thorough documentation has been made of the vascular plants of Majuro Atoll. There were only reports that were either part of much larger discussions on the entire Micronesian region or the Marshall Islands as a whole, and were of a very limited scope. Previous reports by Fosberg, Sachet & Oliver (1979, 1982, 1987) presented only 115 vascular plants on Majuro Atoll. In this study, 563 vascular plants have been recorded on Majuro. INTRODUCTION The accompanying report presents a complete flora of Majuro Atoll, which has never been done before. It includes a listing of all species, notation as to origin (i.e. indigenous, aboriginal introduction, recent introduction), as well as the original range of each. The major synonyms are also listed. For almost all, English common names are presented. Marshallese names are given, where these were found, and spelled according to the current spelling system, aside from limitations in diacritic markings. A brief notation of location is given for many of the species. The entire list of 563 plants is provided to give the people a means of gaining a better understanding of the nature of the plants of Majuro Atoll. -

Redalyc.ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER?

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica BACKHOUSE, GARY N. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 7, núm. 1-2, marzo, 2007, pp. 28- 43 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339813005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 7(1-2): 28-43. 2007. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA GARY N. BACKHOUSE Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Division, Department of Sustainability and Environment 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia [email protected] KEY WORDS:threatened orchids Australia conservation status Introduction Many orchid species are included in this list. This paper examines the listing process for threatened Australia has about 1700 species of orchids, com- orchids in Australia, compares regional and national prising about 1300 named species in about 190 gen- lists of threatened orchids, and provides recommen- era, plus at least 400 undescribed species (Jones dations for improving the process of listing regionally 2006, pers. comm.). About 1400 species (82%) are and nationally threatened orchids. geophytes, almost all deciduous, seasonal species, while 300 species (18%) are evergreen epiphytes Methods and/or lithophytes. At least 95% of this orchid flora is endemic to Australia.