Branded Stance-Taking in US Electoral Politics1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kinney Zalesne

KINNEY ZALESNE 2008 TCG National Conference June 12, 2008 “microtrends: the small forces behind tomorrow’s big changes” Kinney Zalesne SUSAN BOOTH My job is to introduce our first speaker and before I do, I want to let you know that after she’s done speaking, we are going to have about fifteen minutes for some Q&A, so store away those questions. She would be more than happy to respond to them after her remarks. It is a great pleasure to kick off our time together with Kinney Zalesne. She is the co-author, with Mark Penn, of Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow’s Big Changes. Kinney Zalesne is an authority on small communities and social entrepreneurship. With Mr. Penn, she worked on the 1996 Clinton/Gore election campaign and provided strategy for Senator Clinton’s presidential bid. She was a White House fellow in Al Gore’s office, focusing on domestic policy and education technology. She worked as counsel to attorney general Janet Reno in the mid-90’s. And here’s what’s cool: she left all of that to become president of College Summit, a not-for-profit that helps low-income school districts send kids to college. She’s a graduate of both Yale University and Harvard Law School and it’s my delight to welcome to the stage Kinney Zelesne. [Applause] KINNEY ZALESNE Thank you very much Susan and Kent and Teresa and all of you for having me here. What Susan didn’t tell you about my biography is really what’s most important to me is that in Junior High, I was quite the actress. -

Just 1% the Power of Microtrends by Mark Penn & E. Kinney Zalesne

Just 1% The Power of Microtrends By Mark Penn & E. Kinney Zalesne Info NEXT An Introduction to Microtrends In 1960, Volkswagen shook up the car world with a full-page ad containing just two words: THINK SMALL. It was revolutionary—a call for the shrinking of perspective in an era when success was all about gain, even when you were just driving down the street. America never quite got used to small when it came to cars. But ask two-thirds of America, and they’ll tell you they work for small business. We yearn for the lifestyles of small-town America. Many of the biggest movements in America today are small—hidden, for just a few to see. Microtrends is based on the idea that the most powerful forces in our society are the emerging, counter-intuitive trends shaping tomorrow right before us. With so much focus on poverty as the cause of terrorism, it is hard to see that it is richer, educated terrorists who have been behind many of the attacks. With so much attention to big, organized religion, it is hard to see that it is newer, small sects that are the fastest-growing. But small choices have redefined society. We used to live in the “Ford economy,” where workers created one black car, over and over, for thousands of consumers. Now we live in the “Starbucks economy,” where workers create thousands of different cups of coffee, for individual customers. That explosion of choice has, in turn, created hundreds of small, intense communities defining themselves in new ways. -

Wählermobilisierungsstrategien Von Hispanics in Den US-Präsidentschaftswahlkämpfen Der Jahre 2000 – 2008

Wählermobilisierungsstrategien von Hispanics in den US-Präsidentschaftswahlkämpfen der Jahre 2000 – 2008 Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln 2013 vorgelegt von Diplom-Kulturwirtin Simone Pott aus Rheine 2 Referent: Professor Dr. Thomas Jäger Koreferent: Professor Dr. Wolfgang Leidhold Tag der Promotion: 13.01.2014 3 I. EINFÜHRUNG 6 I.1 HISPANICS UND IHRE BEDEUTUNG IM US-PRÄSIDENTSCHAFTSWAHLKAMPF 6 I.2 FRAGESTELLUNG UND ERKENNTNISINTERESSE 15 I.3 LITERATUR UND QUELLEN 16 I.4 FORSCHUNGSDESIGN UND METHODE 17 II. POLITISCHES MARKETING 17 II.1 DAS POLITISCHE MARKETING IM US-PRÄSIDENTSCHAFTSWAHLKAMPF 17 II.1.1 WÄHLERSEGMENTIERUNG 19 II.1.2 DIE POSITIONIERUNG DES KANDIDATEN UND DAS „CANDIDATE CONCEPT“ 21 II.1.3 DIE FORMULIERUNG UND UMSETZUNG DER STRATEGIE 23 II.1.3.1 DAS KOMMUNIKATIONSPROGRAMM 24 II.1.3.1.1 DER EINSATZ VON WAHLWERBESPOTS 25 II.1.3.1.2 DAS MEDIENMANAGEMENT DER „FREIEN“ PRESSE/“UNPAID NEWS“ 27 II.1.3.1.2.1 AGENDA-SETTING 30 II.1.3.1.2.2 PRIMING 31 II.1.3.1.2.3 FRAMING 32 II.1.3.1.3 DER EINSATZ TYPISCHER SYMBOLE IM US-PRÄSIDENTSCHAFTSWAHLKAMPF 33 II.1.3.1.3.1 RELIGION ALS SYMBOL 34 II.1.3.1.3.2 POLITISCHE SPRACHE 36 II.1.3.1.3.3 KULTURKAMPF 37 II.1.3.2 “GET-OUT-THE-VOTE” 38 II.2 DIE POLITISCHEN AKTEURE IM WAHLKAMPF 38 II.3 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG DER ZENTRALEN PUNKTE 44 III. FALLSTUDIE PRÄSIDENTSCHAFTSWAHLKAMPF 2000 46 III.1 DIE SITUATION DER USA ZUM PRÄSIDENTSCHAFTSWAHLKAMPF 2000 46 III.2 DIE WAHLKAMPFSTRATEGIEN 46 III.3 DAS „CANDIDATE CONCEPT“ -

Leadership Lessons of the White House Fellows

“Leadership Lessons of White House Fellows takes a close look at the young Americans who have participated in this program and at their interesting and absorbing stories and insights.” —The Honorable Elaine L. Chao, former United States Secretary of Labor, President and CEO of United Way of America, Director of the Peace Corps “The lessons I learned as a White House Fellow have informed my leadership principles and influenced me deeply throughout my career. In this powerful and insightful book, Garcia shows readers how to use these same lessons within their lives.” —Marshall Carter, Former Chairman and CEO, State Street Bank and Trust; Senior Fellow, Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government “This is a reflective and compelling account of how a remarkable program shaped the lives of many of America’s best leaders – and continues to shape the leaders that we’ll need in our future.” —Clayton M. Christensen, Robert & Jane Cizik Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School; bestselling author of Innovator’s Prescription, Disrupting Class, and The Innovator’s Dilemma “This book is full of illuminating leadership lessons that teach and inspire.” —Roger B. Porter, IBM Professor of Business and Government, Harvard University “Garcia has done a tremendous service by writing this book. There is abso- lutely no better training ground for the next generation of leaders than the White House Fellows Program.” —Myron E. Ullman, III, Chairman and CEO of J.C. Penney and Chairman of the National Retail Federation “Charlie Garcia’s book recounts the stories of Americans who have given their lives to public service, and explains in their own words the “how” that made them effective servant leaders. -

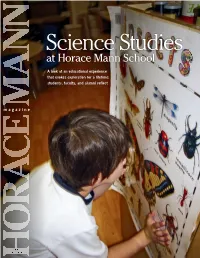

Science Studies at Horace Mann School, from the Nursery Division Through the Upper, Encourage Exploration

Science Studies at Horace Mann School A look at an educational experience that evokes exploration for a lifetime: students, faculty, and alumni reflect magazine Volume 4 Number 1 SPRING 2008 HORACE MANN HORACE SAVE THE DATE Saturday, September 20, 2008 HOMECOMING HOMECOMING • Alumni Association of Color Reception, Friday, September 19 • Varsity Athletic Events AND REUNION • Fall Frolic with special activities for families and children • Pep Rally Club Events CELEBRATION • Dan Alexander Alumni Soccer Game 2008 • Barbeque Luncheon on Clark Field and Campus Tours REUNIONS Reunion luncheons, cocktail receptions and dinners Classes of 1933, 1938, 1943, 1948, 1953, 1958, 1963, 1968, 1973, 1978, 1983, 1988, 1993, 1998, 2003 For more information visit our website www.horacemannalumni.org or call 718.432.3450. Contentscontents 2 LETTERS 4 GREETINGS FROM THE HEAD OF SCHOOL 5 GREETIN G S F R O M T H E D I R E C T O R O F D EVE L OP M ENT 6 Science studies at Horace Mann School, from the Nursery Division through the Upper, encourage exploration. At Horace Mann School science is a vital part of the curriculum, as it has always been. Students in the youngest grades get their first sense of scientific exploration by investigating the world around them, learning to make hypotheses, and by performing The John Dorr Nature Laboratory provides students an outside-the-classroom basic experiments. As students travel through the opportunity for scientific exploration. (Photo John Dorr Nature Laboratory) Lower and Middle Divisions, scientific methods and procedures are added to their work, while projects and horace mann school journal experiments in the Science Center and at the John Dorr Nature Laboratory enhance the learning experience. -

Academic References

Academic References Aberbach, J. D. and Tom Christensen (2005). ‘Citizens and Consumers.’ Public Management Review, 7(2): 226–245. Aberbach, J. D. and B. A. Rockman (2002). ‘Conducting and Coding Elite Interviews.’ PS: Political Science and Politics, 35(4): 673–676. Ackerman, J. (2004). ‘Co-governance for Accountability: Beyond “Exit” and “Voice”.’ World Development, 32(3): 447–463. Ackerman, B. A. and J. S. Fishkin (2004). Deliberation Day. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Adams, D. and M. Hess (2001). ‘Community in Public Policy: Fad or Founda- tion?.’ Australian Journal of Public Administration, 60(2): 13–23. Allington, N., Philip Morgan and Nicholas O’Shaughnessy (1999). ‘How Marketing Changed the World. The Political Marketing of an Idea: A Case Study of Privatization,’ Chapter 34, in Bruce Newman (ed.), Handbook of Political Marketing, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 627–642. Arnstein, S. R. (1969). ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation.’ Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4): 216–224. Arterton, F. Christopher (2007). ‘Strategy and Politics: The Example of the United States of America,’ in T. Fischer, G. Peter Scmitz and M. Seberich (eds), The Strategy of Politics: Results of a Comparative Study, Butersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, pp. 133–172. Aspinwall, M. (2006). ‘Studying the British.’ Politics, 26(1): 3–10. Atkinson, R. D. and Andrew Leigh (2003). ‘Serving the Stakeholders. Customer- Oriented E-Government: Can We Ever Get There?.’ Journal of Political Marketing, 2(3/4): 159–181. Baines, P. R. (1999). ‘Voter Segmentation and Candidate Positioning,’ in B. Newman (ed.), Handbook of Political Marketing, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, pp. -

![D3bee76 [Pdf] Microtrends: the Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6730/d3bee76-pdf-microtrends-the-small-forces-behind-tomorrows-big-changes-mark-penn-e-kinney-zalesne-8366730.webp)

D3bee76 [Pdf] Microtrends: the Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne

[Pdf] Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne - free pdf download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes by Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne Download, Free Download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Ebooks Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne, Free Download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Full Version Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne, PDF Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Free Download, Read Online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Ebook Popular, free online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes, pdf download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes, Download Free Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Book, Download Online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Book, the book Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes, Download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes E-Books, Download Online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Book, Download pdf Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes, Read Online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes E-Books, Read Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Full Collection, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Ebooks, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes pdf read online, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Popular Download, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Free PDF Download, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Book Download, CLICK FOR DOWNLOAD I thought i'd read it. -

A Citizens' Guide to Understanding Campaigns and Elections

POLITAINMENT: THE TEN RULES OF CONTEMPORARY POLITICS A citizens’ guide to understanding campaigns and elections David Schultz Copyright © 2012 David Schultz All rights reserved. ISBN: 0615594204 ISBN-13: 978-0615594200 politainer (pawl.i.TAYN.ur) n. A politician who is or was an entertainer; a politician who makes extensive use of entertainment media, particularly during a campaign. —adj. —politainment n. http://www.wordspy.com/words/politainer.asp Contents Acknowledgments Welcome to the New World of Politainment 1 The Ten Rules in a Nutshell 6 Rule 1: Politics Is Like Selling Beer 7 (Politics is about telling a story.) Rule 2: Annie’ Is Right 16 (Politics is always about tomorrow.) Rule 3: Rod Stewart Is Right 23 (Politics is about passion.) Rule 4: Politics Is About Mobilizing Your Base 26 (It is also about demobilizing the opposition.) Rule 5: It’s a Bar Fight 37 (Politics is about winning over the swing voter.) Rule 6: Woody Allen Was Right 41 (Politics is about who shows up; 90% of life is showing up.) Rule 7: Image Is Everything 46 (Politics is about defining or being defined.) Rule 8: The Multimedia Is the Message 49 (Politics is about using the best new technologies to communicate a message.) Rule 9: Be True to Yourself 57 (Politics is about being who you are and being a clown; be real and laugh at yourself.) Rule 10: Show Me the Money 61 (Politics is a business.) Three Final Rules 64 About the Author 67 Acknowledgments After nearly 25 years of teaching, countless interviews with reporters, and hundreds of presentations, it is impossible to acknowledge and thank all those individuals who have helped me develop and refine the ideas in this book. -

Harvard International Law Journal

HARVARD JSEL VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1 – SPRING 2010 Contents Preface Peter A. Carfagna & Paul C. Weiler Editor’s Note Ashwin M. Krishnan Articles Judicial Erosion of Protection for Defendants in Obscenity Prosecutions?: When Courts Say, Literally, Enough is Enough and When Internet Availability Does Not Mean Acceptance Clay Calvert, Wendy Brunner, Karla Kennedy & Kara Murrhee The NBA and the Single Entity Defense: A Better Case? Michael A. McCann Hardball Free Agency: The Unintended Demise of Salary Arbitration in Major League Baseball Eldon L. Ham & Jeffrey Malach Wiki Authorship, Social Media and the Curatorial Audience Jon M. Garon The Integrity of the Game: Professional Athletes and Domestic Violence Bethany P. Withers Case Comment In re Dewey Ranch Hockey Ryan Gauthier HARVARD JSEL VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1 – SPRING 2010 Contents Copyright © 2010 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Preface Peter A. Carfagna & Paul C. Weiler 1 Editor’s Note Ashwin M. Krishnan 3 Articles Judicial Erosion of Protection for Defendants in Obscenity Prosecutions?: When Courts Say, Literally, Enough is Enough and When Internet Availability Does Not Mean Acceptance Clay Calvert, Wendy Brunner, Karla Kennedy & Kara Murrhee 7 The NBA and the Single Entity Defense: A Better Case? Michael A. McCann 39 Hardball Free Agency: The Unintended Demise of Salary Arbitration in Major League Baseball Eldon L. Ham & Jeffrey Malach 63 Wiki Authorship, Social Media and the Curatorial Audience Jon M. Garon 95 The Integrity of the Game: Professional Athletes and Domestic Violence Bethany P. Withers 145 Case Comment In re Dewey Ranch Hockey Ryan Gauthier 181 Volume 1 Harvard Journal of Sports Number 1 Spring 2010 & Entertainment Law EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-Chief Ashwin M. -

Soundingthe Mystic Chords of Memory': Musical Memorials For

Sounding “The Mystic Chords of Memory”: Musical Memorials for Abraham Lincoln, 1865–2009 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Thomas J. Kernan BM, University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2005 MM, University of Cincinnati, 2010 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD ABSTRACT Composers have memorialized Abraham Lincoln in musical works for the home, concert hall, and theater stage from his death in 1865 to, most recently, the 2009 bicentennial of his birth. They have invoked the name, biography, or character of Lincoln in compositions that address social, cultural, and political movements of their own times and places. In this study I consider the music composed and performed during Lincoln’s national funeral, Reconstruction, periods of mass immigration, the Civil Rights Movement, and the bicentennial of the president’s birth. In this music composers have portrayed Lincoln as martyr and saint, political advocate, friend to the foreigner and common man, and champion of equality. This study touches on issues of modernism and postmodernism, with specific consideration of changes in funerary and mourning rituals as well as the consequences of industrialization, commercialization, and the internet age in shaping presidential legacies. Careful attention is paid to aspects of ritual, protest, and cultural change. I argue that composers, through their memorial songs, symphonies, and dramas, have shared in creating our historical memory of the first martyred president. Moreover, I posit that the American desire for a civic leader with recognizable moral security, to which subsequent generations have bound their causes, has led to a series of changes in the Lincoln topos itself. -

The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne

[PDF] Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne - pdf download free book Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes PDF, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes by Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne Download, Free Download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Ebooks Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne, PDF Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Popular Download, Read Online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes E-Books, Free Download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Full Version Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne, Read Online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Ebook Popular, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Free Read Online, PDF Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Full Collection, free online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes, pdf free download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes, by Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes, Mark Penn, E. Kinney Zalesne ebook Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes, Download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Online Free, Read Online Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes E-Books, Read Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Full Collection, Read Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Ebook Download, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Read Download, PDF Download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Free Collection, Free Download Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Books [E-BOOK] Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes Full eBook, CLICK HERE FOR DOWNLOAD Where do we turn the ludicrous.