Economic Freedoms and the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Originalism and Stare Decisis Amy Coney Barrett Notre Dame Law School

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 92 | Issue 5 Article 2 7-2017 Originalism and Stare Decisis Amy Coney Barrett Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Judges Commons Recommended Citation 92 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1921 (2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\92-5\NDL502.txt unknown Seq: 1 5-JUL-17 15:26 ORIGINALISM AND STARE DECISIS Amy Coney Barrett* INTRODUCTION Justice Scalia was the public face of modern originalism. Originalism maintains both that constitutional text means what it did at the time it was ratified and that this original public meaning is authoritative. This theory stands in contrast to those that treat the Constitution’s meaning as suscepti- ble to evolution over time. For an originalist, the meaning of the text is fixed so long as it is discoverable. The claim that the original public meaning of constitutional text consti- tutes law is in some tension with the doctrine of stare decisis. Stare decisis is a sensible rule because, among other things, it protects the reliance interests of those who have structured their affairs in accordance with the Court’s existing cases. But what happens when precedent conflicts with the original meaning of the text? If Justice Scalia is correct that the original public mean- ing is authoritative, why is the Court justified in departing from it in the name of a judicial policy like stare decisis? The logic of originalism might lead to some unpalatable results. -

Robert L. Tsai

ROBERT L. TSAI Professor of Law American University The Washington College of Law 4300 Nebraska Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20016 202.274.4370 [email protected] roberttsai.com EDUCATION J.D. Yale Law School, 1997 The Yale Law Journal, Editor, Volume 106 Yale Law and Policy Review, Editor, Volume 12 Honorable Mention for Oral Argument, Harlan Fiske Stone Prize Finals, 1996 Morris Tyler Moot Court of Appeals, Board of Directors Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic B.A. University of California, Los Angeles, History & Political Science, magna cum laude, 1993 Phi Beta Kappa Highest Departmental Honors (conferred by thesis committee) Carey McWilliams Award for Best Honors Thesis: Building the City on the Hilltop: A Socio-Political Study of Early Christianity ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Temple University, Beasley School of Law Clifford Scott Green Chair and Visiting Professor of Constitutional Law, Fall 2019 Courses: Fourteenth Amendment History and Practice, Presidential Leadership Over Individual Rights American University, The Washington College of Law Professor of Law, May 2009—Present Associate Professor of Law (with tenure), June 2008—May 2009 Courses: Constitutional Law, Criminal Procedure, Jurisprudence, Presidential Leadership and Individual Rights, The First Amendment University of Georgia Law School Visiting Professor, Semester in Washington Program, Spring & Fall 2012 Course: The American Presidency and Individual Rights University of Oregon School of Law Associate Professor of Law (with tenure), 2007-08 Assistant Professor, 2002-07 2008 Lorry I. Lokey University Award for Faculty Excellence (via nomination & peer review) 2007 Orlando John Hollis Faculty Teaching Award Courses: Constitutional Law, Federal Courts, Free Speech, Equality, Religious Freedom, Civil Rights Litigation Yale University, Department of History Teaching Fellow, 1996, 1997 CLERKSHIPS The Honorable Hugh H. -

Yale Law & Policy Review Inter Alia

Essay - Keith Whittington - 09 - Final - 2010.06.29 6/29/2010 4:09:42 PM YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW INTER ALIA The State of the Union Is a Presidential Pep Rally Keith E. Whittington* Introduction Some people were not very happy with President Barack Obama’s criticism of the U.S. Supreme Court in his 2010 State of the Union Address. Famously, Justice Samuel Alito was among those who took exception to the substance of the President’s remarks.1 The disagreements over the substantive merits of the Citizens United case,2 campaign finance, and whether that particular Supreme Court decision would indeed “open the floodgates for special interests— including foreign corporations—to spend without limits in our elections” are, of course, interesting and important.3 But the mere fact that President Obama chose to criticize the Court, and did so in the State of the Union address, seemed remarkable to some. Chief Justice John Roberts questioned whether the “setting, the circumstances and the decorum” of the State of the Union address made it an appropriate venue for criticizing the work of the Court.4 He was not alone.5 Criticisms of the form of President Obama’s remarks have tended to focus on the idea that presidential condemnations of the Court were “demean[ing]” or “insult[ing]” to the institution or the Justices or particularly inappropriate to * William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Politics, Princeton University. I thank Doug Edlin, Bruce Peabody, and John Woolley for their help on this Essay. 1. Justice Alito, who was sitting in the audience in the chamber of the House of Representatives, was caught by television cameras mouthing “not true” in reaction to President Obama’s characterization of the Citizens United decision. -

Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum to Claims Court - Law360

9/24/2020 Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum To Claims Court - Law360 Portfolio Media. Inc. | 111 West 19th Street, 5th floor | New York, NY 10011 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum To Claims Court By Julia Arciga Law360 (September 22, 2020, 2:46 PM EDT) -- A Maryland-based former Kirkland & Ellis LLP associate will become a judge of the Court of Federal Claims for a 15-year term, after the U.S. Senate on Tuesday confirmed him by a 66-27 vote. Edward H. Meyers is a partner at Stein Mitchell Beato & Missner LLP, litigating bid protests, breach of contract disputes and copyright infringement. While at the firm, he served as counsel for one of the collection agencies in a 2018 consolidated protest action challenging the U.S. Department of Education's solicitation for student loan debt collection services. He clerked with Federal Claims Judge Loren A. Smith between 2005 and 2006 before spending six years as a Kirkland associate, where he worked as a civil litigator handling securities, government contracts, construction, insurance and statutory claims. He earned his bachelor's degree from Vanderbilt University and his law degree summa cum laude from Catholic University of America's Columbus School of Law — where he joined the Federalist Society and still remains a member. Judiciary committee members Sens. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., had raised questions about Meyers' Federalist Society affiliation before Tuesday's vote, and he confirmed that he did speak to fellow members throughout his nomination process. -

Originalism and Constitutional Construction

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Originalism and Constitutional Construction Lawrence B. Solum Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1301 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2307178 82 Fordham L. Rev. 453-537 (2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Legal Theory Commons ORIGINALISM AND CONSTITUTIONAL CONSTRUCTION Lawrence B. Solum* Constitutional interpretation is the activity that discovers the communicative content or linguistic meaning of the constitutional text. Constitutional construction is the activity that determines the legal effect given the text, including doctrines of constitutional law and decisions of constitutional cases or issues by judges and other officials. The interpretation-construction distinction, frequently invoked by contemporary constitutional theorists and rooted in American legal theory in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, marks the difference between these two activities. This Article advances two central claims about constitutional construction. First, constitutional construction is ubiquitous in constitutional practice. The central warrant for this claim is conceptual: because construction is the determination of legal effect, construction always occurs when the constitutional text is applied to a particular legal case or official decision. Although some constitutional theorists may prefer to use different terminology to mark the distinction between interpretation and construction, every constitutional theorist should embrace the distinction itself, and hence should agree that construction in the stipulated sense is ubiquitous. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at the National Rifle Association Leadership Forum in Atlanta, Georgia April 28

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at the National Rifle Association Leadership Forum in Atlanta, Georgia April 28, 2017 Thank you, Chris, for that kind introduction and for your tremendous work on behalf of our Second Amendment. Thank you very much. I want to also thank Wayne LaPierre for his unflinching leadership in the fight for freedom. Wayne, thank you very much. Great. I'd also like to congratulate Karen Handel on her incredible fight in Georgia Six. The election takes place on June 20. And by the way, on primaries, let's not have 11 Republicans running for the same position, okay? [Laughter] It's too nerve-shattering. She's totally for the NRA, and she's totally for the Second Amendment. So get out and vote. She's running against someone who's going to raise your taxes to the sky, destroy your health care, and he's for open borders—lots of crime—and he's not even able to vote in the district that he's running in. Other than that, I think he's doing a fantastic job, right? [Laughter] So get out and vote for Karen. Also, my friend—he's become a friend—because there's nobody that does it like Lee Greenwood. Wow. [Laughter] Lee's anthem is the perfect description of the renewed spirit sweeping across our country. And it really is, indeed, sweeping across our country. So, Lee, I know I speak for everyone in this arena when I say, we are all very proud indeed to be an American. -

NONDELEGATION and the UNITARY EXECUTIVE Douglas H

NONDELEGATION AND THE UNITARY EXECUTIVE Douglas H. Ginsburg∗ Steven Menashi∗∗ Americans have always mistrusted executive power, but only re- cently has “the unitary executive” emerged as the bogeyman of Amer- ican politics. According to popular accounts, the idea of the unitary executive is one of “presidential dictatorship”1 that promises not only “a dramatic expansion of the chief executive’s powers”2 but also “a minimum of legislative or judicial oversight”3 for an American Presi- dent to exercise “essentially limitless power”4 and thereby to “destroy the balance of power shared by our three co-equal branches of gov- ernment.”5 Readers of the daily press are led to conclude the very notion of a unitary executive is a demonic modern invention of po- litical conservatives,6 “a marginal constitutional theory” invented by Professor John Yoo at UC Berkeley,7 or a bald-faced power grab con- jured up by the administration of George W. Bush,8 including, most ∗ Circuit Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. ∗∗ Olin/Searle Fellow, Georgetown University Law Center. The authors thank Richard Ep- stein and Jeremy Rabkin for helpful comments on an earlier draft. 1 John E. Finn, Opinion, Enumerating Absolute Power? Who Needs the Rest of the Constitution?, HARTFORD COURANT, Apr. 6, 2008, at C1. 2 Tim Rutten, Book Review, Lincoln, As Defined by War, L.A. TIMES, Oct. 29, 2008, at E1. 3 Editorial, Executive Excess, GLOBE & MAIL (Toronto), Nov. 12, 2008, at A22. 4 Robyn Blumner, Once Again We’ll Be a Nation of Laws, ST. -

Reviewing Randy Barnett, Restoring the Lost Constitution: the Presumption of Liberty (2004

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2007 Restoring the Right Constitution? (reviewing Randy Barnett, Restoring the Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty (2004)) Eduardo Peñalver Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Eduardo Peñalver, "Restoring the Right Constitution? (reviewing Randy Barnett, Restoring the Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty (2004))," 116 Yale Law Journal 732 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDUARDO M. PENALVER Restoring the Right Constitution? Restoringthe Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty BY RANDY E. BARNETT NEW JERSEY: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2004. PP. 384. $49.95 A U T H 0 R. Associate Professor, Cornell Law School. Thanks to Greg Alexander, Rick Garnett, Abner Greene, Sonia Katyal, Trevor Morrison, and Steve Shiffrin for helpful comments and suggestions. 732 Imaged with the Permission of Yale Law Journal REVIEW CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 734 I. NATURAL LAW OR NATURAL RIGHTS? TWO TRADITIONS 737 II. BARNETT'S NONORIGINALIST ORIGINALISM 749 A. Barnett's Argument 749 B. Writtenness and Constraint 752 C. Constraint and Lock-In 756 1. Constraint 757 2. Lock-In 758 D. The Nature of Natural Rights 761 III. REVIVING A PROGRESSIVE NATURALISM? 763 CONCLUSION 766 733 Imaged with the Permission of Yale Law Journal THE YALE LAW JOURNAL 116:73 2 2007 INTRODUCTION The past few decades have witnessed a dramatic renewal of interest in the natural law tradition within philosophical circles after years of relative neglect.' This natural law renaissance, however, has yet to bear much fruit within American constitutional discourse, especially among commentators on the left. -

Windsor: Lochnerizing on Marriage?

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 64 Issue 3 Article 10 2014 Windsor: Lochnerizing on Marriage? Sherif Girgis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sherif Girgis, Windsor: Lochnerizing on Marriage?, 64 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 971 (2014) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol64/iss3/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 64·Issue 3·2014 Windsor: Lochnerizing on Marriage? Sherif Girgis† Abstract This Article defends three insights from Justice Alito’s Windsor dissent. First, federalism alone could not justify judicially gutting DOMA. As I show, the best contrary argument just equivocates. Second, the usual equal protection analysis is inapt for such a case. I will show that DOMA was unlike the policies struck down in canonical sex-discrimination cases, interracial marriage bans, and other policies that involve suspect classifications. Its basic criterion was a couple’s sexual composition. And this feature—unlike an individual’s sex or a couple’s racial composition—is linked to a social goal, where neither link nor goal is just invented or invidious. Third, and relatedly, to strike down DOMA on equal protection grounds, the Court had to assume the truth of a “consent-based” view of the nature of marriage and the social value of recognizing it, or the falsity of a “conjugal” view of the same value and policy judgments. -

The Tea Party Movement As a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 Albert Choi Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/343 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2014 i Copyright © 2014 by Albert Choi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. THE City University of New York iii Abstract The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi Advisor: Professor Frances Piven The Tea Party movement has been a keyword in American politics since its inception in 2009. -

Legal Naturalism Is a Disjunctivism Roderick T. Long Legal Positivists

Legal Naturalism Is a Disjunctivism Roderick T. Long Auburn University aaeblog.com | [email protected] Abstract: Legal naturalism is the doctrine that a rule’s status as law depends on its moral content; or, in its strongest form, that “an unjust law is not a law.” By drawing an analogy between legal naturalism and perceptual disjunctivism, I argue that this doctrine is more defensible than is generally thought, and in particular that it entails no conflict with ordinary usage. Legal positivists hold that a rule’s status as law never depends on its moral content. In Austin’s famous formulation: “The existence of law is one thing; its merit or demerit is another. Whether a law be is one enquiry; whether it ought to be, or whether it agree with a given or assumed test, is another and different inquiry.”1 There seems to be no generally accepted term for the opposed view, that a rule’s status as law does (sometimes or always) depend on its moral content. Legal moralism would be the natural choice, but that name is already taken to mean the view that the law should impose social standards of morality on private conduct. Legal normativisim, another natural choice, is, somewhat perversely, already in use to denote a species of legal positivism.2 The position in question is sometimes referred to as “the natural law view,” but this is not really accurate; although the view has been held by many natural law theorists, it has not been held by all of them, and is not strictly implied by the natural law position. -

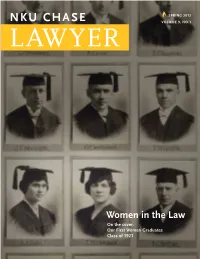

NKU CHASE Volume 9, No.1

Spring 2012 nKu CHASe volume 9, no.1 Women in the law on the cover: our First Women graduates Class of 1921 From the Dean n this issue of NKU Chase Lawyer, we celebrate the success of our women graduates. The law school graduated its first women in 1921. Since then, women have continued to be part of the Interim Editor IChase law community and have achieved success in a David H. MacKnight wide range of fields. At the same time, it is important to Associate Dean for Advancement recognize that there is much work to be done. Design If we are to be true to our school’s namesake, Chief Paul Neff Design Justice Salmon P. Chase, Chase College of Law should be a leader in promoting gender diversity. As Professor Photography Richard L. Aynes, a constitutional scholar, pointed out Wendy Lane in his 1999 article1, Chief Justice Chase was an early Advancement Coordinator supporter of the right of women to practice law. In 1873, then Chief Justice Chase cast John Petric the sole dissenting vote in Bradwell v. Illinois, a case in which the Court in a 8-1 decision Image After Photography LLC upheld the Illinois Supreme Court’s refusal to admit Myra Bradwell to the bar on the Bob Scheadler grounds that she was a married woman. The Court’s refusal to grant Mrs. Bradwell the Daylight Photo relief she sought is all the more notable because three of the justices who voted to deny her relief had previously dissented vigorously in The Slaughter-House Cases, a decision in Timothy D.