Exchange Marriages in the Community Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Name Cnic No./Passport No. Name Address

Format for Reporting of Unclaimed Deposits. Instruments Surrendered to SBP Period of Surrendered (2016): Bank Code: 1279 Bank Name : THE PUNJAB PROVINCIAL COOPERATIVE BANK LIMITED HEAD OFFICE LAHORE Last date of DETAIL OF THE BRANCH NAME OF THE PROVINCE IN DETAIL OF THE DEPOSTOER BENEFICIARY OF THE INSTRUMENT DETAIL OF THE ACCOUNT DETAIL OF THE INSTRUMENT TRANSACTION deposit or WHICH ACCOUNT NATURE ACCOUNT Federal. Curren Rate FCS Rat Rate NAME OF THE INSTRUMENT Remarks S.NO CNIC NO./PASSPORT OF THE TYPE ( e.g INSTRUME DATE OF Provincial cy Type. Contract e Appli Amount Eqr. PKR withdrawal CODE NAME OPENED.INSTRUMENT NAME ADDRESS ACCOUNT NUMBER APPICANT. TYPE (DD, PO, NO. DEPOSIT CURRENT NT NO. ISSUE (FED.PRO)I (USD, ( No (if of ed Outstanding surrendered (DD-MON- PAYABLE PURCHASER FDD, TDR, CO) (LCY,UF , SAVING , n case of EUR, MTM, any) PK date YYYY) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8695206-3 KAMAL-UD-DIN S.O ALLAH BUKHSH ARCS SAHIWAL, TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011001 PLS PKR 1,032.00 1,032.00 18/07/2005 2 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8795426-9 ALI MUHAMMAD S.O IMAM DIN H. NO. 196 FAREED TOWN SAHIWAL,TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011101 PLS PKR 413.00 413.00 11/07/2005 3 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8395698-7 MUHAMMAD SALEEM CHAK NO. 80.6-R TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011301 PLS PKR 1,656.00 1,656.00 08/03/2005 4 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-3511981-9 ABDUL GHANI S.O ALLAH DITTA FARID TOWN 515.K ,TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011501 PLS PKR 942.00 942.00 04/11/2005 5 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-9956978-9 SHABBIR AHMAD S.O MUHAMMAD RAMZAN CHAK NO. -

Visual Foxpro

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION, MULTAN A- 1 INSTITUTION WISE PASS PERCENTAGE AND GRADING INTER PART-II ANNUAL EXAM 2019 Appeared Passed Pass% Grade A+A B C D E Appeared Passed Pass% Grade A+A B C D E 101042 Govt. Model H.S.S., Khanewal 200125 Govt. Degree College for Women, Jalalpur Pirwala 81 51 62.96 2 8 25 16 207 193 93.24 13 54 77 36 13 101749 Govt. Girls H.S.S. Kukkar Hatta, Kabirwala 200127 Govt. Degree College Makhdoom Rasheed, Multan 11 11 100.0 1 4 4 2 106 52 49.06 2 14 24 11 1 102010 Govt. Girls H.S.S. 35/M, Dunya Pur 200128 Govt. Degree College for Women, Shujabad 42 28 66.67 4 9 14 1 273 203 74.36 17 28 58 78 22 102058 Govt. Higher Secondary School, Lodhran 200129 Govt. Degree College, Jalalpur Pirwala 119 51 42.86 1 4 19 18 9 130 67 51.54 10 20 32 5 103831 Sun Model Girls H.S.S. Shah Ghousabad Suraj Miani, Multan 200138 City College of Science and Commerce (For Boys) Officers Colony, Multan 42 32 76.19 1 10 12 9 553 450 81.37 43 85 137 150 35 103868 Sun Model H.S.S. for Boys Shah Ghousabad Suraj Miani, Multan 200201 Govt. Community Model Nusrat-ul-Islam Girls Inter College Multan Cantt, 28 18 64.29 2 1 5 9 1 64 32 50.00 1 4 11 9 7 106043 Govt. Model Higher Secondary School, Vehari 200206 Govt. -

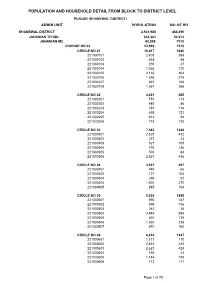

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (KHANEWAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH KHANEWAL DISTRICT 2,921,986 466,390 JAHANIAN TEHSIL 343,361 52,613 JAHANIAN MC 43,598 7010 CHARGE NO 03 43,598 7010 CIRCLE NO 01 10,417 1640 221030101 2,403 388 221030102 614 84 221030103 250 47 221030104 1,065 170 221030105 2,135 304 221030106 1,596 275 221030107 697 106 221030108 1,657 266 CIRCLE NO 02 4,001 655 221030201 751 113 221030202 480 86 221030203 781 116 221030204 658 121 221030205 613 94 221030206 718 125 CIRCLE NO 03 7,583 1226 221030301 2,625 432 221030302 237 43 221030303 521 105 221030304 776 126 221030305 503 84 221030306 2,921 436 CIRCLE NO 04 3,947 657 221030401 440 66 221030402 727 104 221030403 295 52 221030404 1,600 272 221030405 885 163 CIRCLE NO 05 9,034 1485 221030501 990 187 221030502 898 156 221030503 262 38 221030504 3,844 583 221030505 810 135 221030506 1,360 226 221030507 870 160 CIRCLE NO 06 8,616 1347 221030601 1,111 170 221030602 2,812 425 221030603 2,621 424 221030604 156 23 221030605 1,144 188 221030606 772 117 Page 1 of 74 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (KHANEWAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JAHANIAN QH 169,785 25814 055/10-R PC 5,480 875 CHAK NO 053/10-R 1,932 337 221011403 1,124 197 221011404 700 124 221011405 108 16 CHAK NO 054/10-R 2,037 318 221011402 1,133 188 221011406 904 130 CHAK NO 055/10-R 1,511 220 221011401 1,511 220 056/10-R PC 6,093 890 CHAK NO 056/10-R 2,028 307 221011501 1,059 157 221011502 969 150 CHAK NO 057/10-R 2,786 -

British Paradigm of Urban Administrative Centrality: Intransient Continuity in the Postcolonial State

Muhammad Shafique * Lubna Kanwal** British Paradigm of Urban Administrative Centrality: Intransient Continuity in the Postcolonial State Abstract Exploring the British paradigm of the shift of Urban-Administrative centers from one city to other, the paper examines the nature of traditional Urban administrative centers on the one hand and the factors, forces and processes working behind the shift of Urban-Administrative centers on the other hand.. For, exploring the patterns of the development of colonial system of irrigation, settlement and communication/transportation as key factors in the emergence of new Urban centers, it analysis how and why administrative centers were shifted to these new urban centers. The paper also explores the continuity of these colonial patterns of developments and shift of Urban-administrative centrality in postmodern, postcolonial politics administration of a nation state. For, The paper revolves around the theme that colonial paradigm and patterns of development are intransient and even post-colonial patterns of politics of urban-administrative centres is following the same paradigm. For, the paper focuses on mid-nineteenth century urban-administrative configuration of Sara-i-Sidho Tehsil of Multan district of 1849 and examines that how this Tehsil headquarter was later replaced with Kabirwala and how Khanewal district emerge out of these patterns of developments. 1. Introduction: The impact of colonial modernity on South Asian development occupies a central place in the academic discourse on the nature of socio-politics and economics. Having a clear cut stance on the negativity of ‘imperialism/colonialism’, still a large number of intellectuals represent British Imperialism as a ‘lesser evil’ than the other Imperialisms functioning in the history of mankind.1 In the recent debate, three major schools have potentially contributed to the evaluation of British Imperial impact on India. -

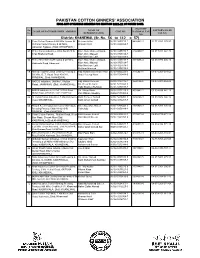

3 List of Members for North Zone Khanewal 2021-22

PAKISTAN COTTON GINNERS' ASSOCIATION PROVISIONAL VOTER LIST FOR ELECTION 2021 - 2022 OF NORTH ZONE FACTORY Sr. NAME OF FACTORY SALES NAME OF FACTORIES WITH ADDRESS CNIC NO. NATIONAL TAX No. REPRESENTATIVE TAX NO. NO. District: KHANEWAL (Sr. No. 46 to 97 = 52) 46 Prime Fiber Ginning Pressing & Oil Mills, Sheikh Abdul Majeed 36103-3705194-7 3973406-4 04-00-3973-406-15 Kabirwala Road,Khanewal Sheikh Ehtasham Latif 36103-4027918-3 Mr.Umar Hameed 36103-1952034-3 47 Prime Cotton Industries, Sheikh Abdul Majeed 36103-3705194-7 2144909-7 04-07-5201-042-73 Chak No.91/10-R, Sheikh Ehtasham Latif 36103-4027918-3 Chak Shahana Road, Anis Latif 36103-2450785-7 48 Zulfiqar Cotton Industries, Bypass,166/10-R, Mian Muhammad Ahmed 35102-7265041-1 3323468-0 04-07-5201-949-37 Mehr Shah, KHANEWAL. Mian Muhammad Asif 35102-7142383-3 49 Akhlaq Brothers Cotton Ginning Pressing Sheikh.Muhammad Akhlaque 36103-3613875-3 2144907-4 04-07-5201-555-82 Factory & Oil Mills, 91/10-R, Shanti Nagar Sheikh Muhammad Naseem 36103-1844624-5 Road, KHANEWAL. 50 Anwer Cotton Industries, Tariq Mehmood Rana 61101-8476866-1 2896909-0 04-00-2896-909-19 Chak Shahana Road' 92/10-R, KHANEWAL. 51 Saim Seed Services Lessee of Khizar Tariq Abdullah 36101-0246514-1 2168727-7 04-00-1404-038-64 Industries, Supper Highway, JAHANIAN. (Distt: KHANEWAL) 52 Haider Khan Cotton Industries, Ginning Mr.Javed Ahmed Khan Daha 35202-2598689-7 4107381-9 04-00-4107-381-12 Pressing & Oil Mills, Chak No: 16/V, Mr.Muhammad Haider Khan 35202-7166415-7 Makhdoom Pur Road, Rubina Javed 35200-1431019-6 Distt: KHANEWAL. -

Institution Wise Pass Percentage Inter Annual Examination 2020

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION, MULTAN A- 1 INSTITUTION WISE PASS PERCENTAGE AND GRADING INTER ANNUAL EXAMINATION 2020 Appeared Passed Pass% Grade A+A B C D E Appeared Passed Pass% Grade A+A B C D E 101042 Govt. Model H.S.S., Khanewal 200107 Govt. College of Science, Multan 50 50 100.0 2 3 18 21 6 332 283 85.24 8 25 84 118 48 101745 Muslim Public Boys H.S.S. 67/15-L Vijhian Wala, Mian Channu 200109 Govt. College for Women Mumtazabad, Multan 6 5 83.33 2 3 785 717 91.34 49 108 231 246 81 2 101749 Govt. Girls H.S.S. Kukkar Hatta, Kabirwala 200110 Govt. College For Women Chungi No.14, Multan 13 10 76.92 2 4 4 487 483 99.18 11 51 139 197 84 1 102010 Govt. Girls H.S.S. 35/M, Dunya Pur 200122 Govt. Degree College for Women Shah Rukn-e-Alam, Multan 46 42 91.30 6 13 21 2 522 480 91.95 8 47 136 209 75 5 102058 Govt. Higher Secondary School, Lodhran 200124 Govt. Degree College for Women Makhdum Rashid, Multan 155 145 93.55 4 11 32 72 25 1 183 176 96.17 4 21 59 75 16 1 102735 Ibn-e-Seena Boys H.S.S. Dokota Road, Dunya Pur 200125 Govt. Degree College for Women, Jalalpur Pirwala 26 24 92.31 5 5 4 9 1 244 240 98.36 28 76 80 47 9 103831 Sun Model Girls H.S.S. -

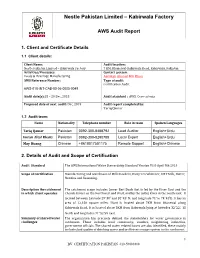

AWS Audit Report

Nestle Pakistan Limited – Kabirwala Factory AWS Audit Report 1. Client and Certificate Details 1.1 Client details: Client Name: Audit location: Nestle Pakistan Limited – Kabirwala Factory 7 KM, Khanewal-Kabirwala Road, Kabirwala, Pakistan Activities/Processes: Contact person: Foods & Beverage Manufacturing Aatekah Ahmad Mir Khan AWS Reference Number: Type of audit: Certification Audit AWS-010-INT-CAB-00-06-0005-0049 Audit date(s):18 – 20 Dec, 2018 Audit standard : AWS Core criteria Proposed date of next audit: Dec, 2019 Audit report completed by: Tariq Qamar 1.2 Audit team: Name Nationality Telephone number Role in team Spoken Languages Tariq Qamar Pakistan 0092-300-8488792 Lead Auditor English+Urdu Imran Altaf Bhatti Pakistan 0092-300-8290788 Local Expert English+Urdu May Huang Chinese +8618017501175 Remote Support English+Chinese 2. Details of Audit and Scope of Certification Audit Standard The AWS International Water Stewardship Standard Version V1.0 April 8th 2014 Scope of Certification Manufacturing and warehouse of Milk Powders, Dairy Tea Whitener, UHT Milk, Butter, Noodles and Seasoning. Description the catchment The catchment scope includes Lower Bari Doab that is fed by the River Ravi and the in which client operates Chenab Rivers on the Northwest and West, and by the Sutluj River in the South East. It located between Latitude 29°30' and 31°45' N. and longitude 71°to 74°45'E. It has an area of 12,150 square miles. Plant is located about 7KM from khanewal along Kabirwala Road. It is located about 3KM from Kabirwala lying at latitudes 32°22’, 18 North and longitudes 71°52’59 East. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Tehsil Municipal Administrations Khanewal

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF TEHSIL MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS KHANEWAL AUDIT YEAR 2015-16 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ....................................................................... i PREFACE ....................................................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ...................................................................... vii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ...................................................................................................... vii Table 2: Audit observations regarding Financial Management ................................................. vii Table 3: Outcome Statistics .......................................................................................................... viii Table 4: Irregularities Pointed Out ................................................................................................. ix Table 5: Cost -Benefit ..................................................................................................................... ix CHAPTER-1 ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Tehsil Municipal Administrations, Khanewal ................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... -

Nestle Kabirwala Factory PROJECT REPORT Investigator

Nestle Kabirwala Factory PROJECT REPORT Vendor Number: 100211157 Assessment of the exploitation level of local water bodies by all water consumers in a radius of 10 km (315 square kilometers area) around Nestle Kabirwala Factory (6.5km Kabirwala Khanewal Road), South Pakistan Investigator Dr. Zulfiqar Ahmad Consultant Hydrogeologist to Nestle HYDROGEOPHYSICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE CONSULTANTS (HESC) NTN-1287293-8 E-MAIL: [email protected] [email protected] (Off) 051-90642167, Kabirwala Factory 1 Kabirwala Factory 2 Kabirwala Factory 3 Kabirwala Factory Satellite Imagery of the Bari Doab (Source: Google Earth, 2015) Assessment of the exploitation level of local water bodies by all water consumers in a radius of 10 km (315 square kilometers area) around Nestle Kabirwala Factory (6.5km Kabirwala Khanewal Road), South 4 Kabirwala Factory Pakistan 1. Executive Summary water consumers in a radius of 10 km (315 square kilometers area) around Nestle range of studies including hydrology and hydrogeology, temperature, rainfall, relative humidity, and spatial distribution of rainfall and temperature in Multan, Khanewal, TobaTek Singh, Jhang, Faisalabad, onsite data collection about fifty three (53) sites for water table, hydraulic heads, construction methodology, year of installation of wells, 5 Kabirwala Factory tentative well discharges and drawdown. Based on these information, contour maps of the water tables, hydraulic heads with vector lines (groundwater elevation map), and direction of groundwater flows 2015 are constructed by a best contouring routine SURFER Version 11. Numerical groundwater modeling study on a regional scale has also been carried out using 3-D Numerical groundwater flow and transport model (Visual ModFlow Software 2013) to develop steady-state and transient (non-steady state) flow models of the historic past in 1962 and most recent version in 2015. -

District Khanewal

ANNUAL POLICING PLAN FOR THE YEAR 2016-17 DISTRICT KHANEWAL District Police Officer Khanewal 1 2 INTRODUCTION Khanewal, previously a Sub-Division of Multan District, attained the status of a district on 1985. It comprises of 04 sub-divisions, namely Khanewal, Kabirwala, Mianchannu and Jahanian having 18 police stations and 4 police posts. Mianchannu Sub- Division was carved out of old Khanewal area at that time whereas Kabirwala Sub-Division as such was attached with the newly created district. Geography Khanewal District lies with a bend made by the rivers before Multan District. It is surrounded by Sahiwal and Khanewal on its east, Multan and Muzaffargarh on its west, Lodhran on its south and Jhang & Toba Tek Sing districts on its north. District Khanewal is a compact administrative unit having an area of 4,349 Sq. kilometers. Three main highways i.e. Lahore – Multan – Khanewal, Khanewal – Lodhran and Kabirwala – Jhang roads pass through Khanewal. Like wise the total distance of link roads falling within the jurisdiction of Khanewal is 1289 kilometers. The river Ravi crosses Khanewal through the jurisdiction of Police Stations Tulamba, Abdul Hakim, Haveli Koranga, Serai Sidhu and Nawan Shehar. There are 03 major canals in this district namely LBDC, Mailsi and Shujabad link canals. District Khanewal has the oldest, largest and most important railway junction of the country. All the major trains moving towards north and south or towards other directions of the country change their course from this point onward. At this junction point, all kinds of trains i.e. electric engine trains or trains with manual engines are running. -

Punjab Basic Urban Services Project

RESETTLEMENT FRAMEWORK, FULL RESETTLEMENT PLAN Supplementary Appendix to the Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors on the SOUTHERN PUNJAB BASIC URBAN SERVICES PROJECT in PAKISTAN Punjab/Local Government and Rural Development Department This report was prepared by the Borrower and is not an ADB document. December 2003 LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT PLAN 1. The Project aims to improve living conditions and quality of life of low income communities in 21 towns of 6 districts in Southern Punjab (see attached site map) where (i) safe drinking water is scarce or unsafe; (ii) sewerage system is inadequate or non-existent and wastewater treatment facilities are absent; and (iii) solid waste collection and disposal is insufficient. The population of majority of the towns ranged from 20,000 to 25,000. The Project will include the following sub-components: (i) sewage system improvement and sewage treatment; (ii) water supply; (iii) solid waste management; (iv) low-income area link roads; and (v) relocation of slaughterhouses. In each Project town, there will be one or two landfill sites for the orderly disposal of municipal solid waste and 1 to 3 wastewater treatment plants which are so far totally absent in all Project towns. The total land requirement for the planned infrastructure facilities, tenure of land, cost of private lands of different categories, number of houses and their average value and the total value of land and houses are shown in Table 1. Table 1 : Land Requirements and Acquisition Cost rren ment -

3-List-Of-Members-For-North-Zone-Khanewal-2019-20.Pdf

PAKISTAN COTTON GINNERS' ASSOCIATION FINAL LIST OF ELIGIBLE MEMBERS FOR ELECTION 2019-20 OF NORTH ZONE. FACTORY Sr. NAME OF FACTORY SALES NAME OF FACTORIES WITH ADDRESS CNIC NO. NATIONAL TAX No. REPRESENTATIVE TAX NO. NO. District: KHANEWAL (Sr. No. 56 to 112 = 57) 56 Pearl Cotton Ginners & Oil Mills Lessee Of Kaleem Akhtar 36103-1602719-1 4426991-9 32-77-8761-275-57 Rehman Cotton Factory & Oil Mills, Khawar Hanif 36103-3269364-7 Jahanian Bypass, (Distt: KHANEWAL) 57 Prime Cotton Industries, Chak No.91/10-R, Mian Abdul Waheed Sajad, 36103-1855738-7 2144909-7 04-07-5201-042-73 Chak Shahana Road, Mian Abdul Majeed 36103-3705194-7 Mian Ithesham Latif 36103-4027918-3 58 Prime Fiber Ginning Pressing & Oil Mills, Mian Abdul Waheed Sajad, 36103-1855738-7 3973406-4 04-00-3973-406-15 Kabirwala Road, Khanewal Mian Abdul Majeed 36103-3705194-7 Mian Ithesham Latif 36103-4027918-3 Mr.Umar Hameed 36103-1952034-3 59 Ahmed Traders Cotton Ginning Pressing & Haji Muhammad Akram Khan 36103-9955223-3 3145964-1 04-07-5201-934-55 Oil Mills, G. T. Road, Chak 80/10-R, Abdul Razzaq Khan 36103-7519418-5 PIROWAL, Distt: KHANEWAL 60 NASCO Industries, Unit No:1, Multan Haji Atta-ur-Rehman 36302-1827012-1 2540706-6 04-07-5201-864-46 Road, JAHANIAN, (Distt: KHANEWAL). Ch. Zia-ur-Rehman 36101-5222868-3 Hafiz Khalil-ur-Rehman 36101-1270197-7 61 NASCO Industries, U # 2, Pull 114/10 K Road, Ch. Iftikhar Nazir 35202-9177226-5 4039841-2 03-00-4039-841-15 Multan Road, JAHANIAN, Distt: KHANEWAL Zain Iftikhar chaudhry 35202-7930459-9 62 Al-Hamd Cotton Industries, 5 KM.