RAR, Volume 22, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jake Berthot

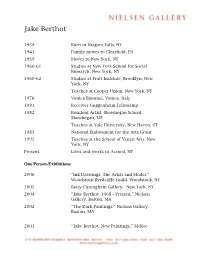

Jake Berthot 1939 Born in Niagara Falls, NY 1941 Family moves to Clearfield, PA 1959 Moves to New York, NY 1960-61 Studies at New York School for Social Research, New York, NY 1960-62 Studies at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York, NY Teaches at Cooper Union, New York, NY 1976 Venice Biennial, Venice, Italy 1981 Receives Guggenheim Fellowship 1982 Resident Artist, Skowhegan School, Skowhegan, ME Teaches at Yale University, New Haven, CT 1983 National Endowment for the Arts Grant 1992 Teaches at the School of Visual Arts, New York, NY Present Lives and works in Accord, NY One Person-Exhibitions 2006 “Ink Drawings: The Artist and Model,” Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, Woodstock, NY 2005 Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2004 "Jake Berthot: 1968 - Present," Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 2002 “The Dark Paintings,” Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 2001 “Jake Berthot, New Paintings,” McKee Gallery, New York, NY 2002 "Landscape Paintings & Drawings," Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 1999 "Trees: Drawings and Texts," Humanities Gallery, The Cooper Union, New York, NY 1998 “Paintings and Drawings,” Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 1997 “New Paintings and Drawings,” McKee Gallery, New York, NY 1996 “Drawings,” McKee Gallery, New York, NY “Enamel Drawings," Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 1995 “Jake Berthot: The Red Paintings,” Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA “Jake Berthot,” Jaffe-Friede and Strauss Galleries, Hopkins Center, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 1994 “Jake Berthot: The Kristin Paintings and Works on Paper,” David McKee Gallery, New York, NY “Jake Berthot : Paintings and Works on Paper,” David McKee Gallery, New York, NY 1992 “Jake Berthot - Paintings,” Toni Oliver Gallery, Sydney, Australia. -

Berthot Press Release 2016

Jake Berthot: In Color March 12 – April 23, 2016 Opening Saturday March 12th, 4 – 7 PM Celebrating the career of Jake Berthot, Betty Cuningham Gallery is pleased to open Jake Berthot: In Color on Saturday, March 12th, with a reception from 4 – 7 PM. The exhibition will include approximately 20 works dating from 1969 to 2014. As this is the first exhibition of Berthot’s work since his death in December of 2014, the Gallery chose to feature Nympha Red, a major work only once exhibited in 1988 at the Rose Art Museum (Brandeis University). Painted in 1969, Nympha Red measures 60 ½ x 210 inches and is the ‘sister painting’ to another major horizontal painting, Walken's Ridge, 1975-6, in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. From these two paintings – painted early in his career – the titles alone indicate Berthot’s instinctive interest in both color and landscape. Berthot began exhibiting in the mid-1960s, at a time when Abstract Expressionism, Pop and Minimalism were part of the aesthetic environment. Berthot’s early work was geometric and the color was subdued. Over the following years, his color intensified and the underlying grid opened to include an oval (some thought a portrait or a head). In 1992, Berthot moved to upstate New York where he wrote a quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson on the wall of his new studio: We may climb into the thin and cold realm of pure geometry and lifeless science, or sink into that of sensation. Between these extremes is the equator of life, of thought, or spirit, or poetry – a narrow belt. -

New Work on Paper I John Elderfield

New work on paper I John Elderfield Author Elderfield, John Date 1981 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2019 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art NEW WORK ON PAPER JAKE BERTHOT DAN CHRISTENSEN ALAN COTE TOM HOLLAND YVONNE JACQUETTE KEN KIFF JOAN SNYDER WILLIAM TUCKER JOHN ELDERFIELD THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK NEW WORK ON PAPER 1 Thisis the first in a seriesof exhibitionsorganized by The Museumof ModernArt, New York, each of whichis intendedto showa relativelysmall number of artists througha broadand representativeselection of their recentwork on paper.Emphasis is placedon newwork, with occasionalglances backward to earlierproduction where the characterof the art especially reguiresit, and on artists or kindsof art not seenin depth at the Museumbefore. Beyond this, no restrictionsare imposedon the series,which may include exhibitions devoted to heterogeneous and to highlycompatible groups of artists, and selectionsof workranging from traditional drawing to workson paper in mediaof all kinds.Without exception, however, the artists includedin each exhibitionare presentednot as a definitive selectionof outstandingcontemporary talents but as a choice, limitedby necessitiesof space, of only a fewof those whose achievementmight warrant their inclusion— and a choice, moreover,that is entirelythe responsibilityof the directorof the exhibition,who wished to share someof the interestand excite mentexperienced in lookingat newwork on paper. NEW WORK ON PAPER 1 JOHN ELDERFIELD THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK Copyright© 1981by The Museumof ModernArt TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM Jr.,Mrs. -

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (Nantes 1836- 1902 Doubs)

THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com James Jacques Joseph Tissot (Nantes 1836- 1902 Doubs) Triumph of the Will – The Challenge Signed “J J Tissot” (lower right) Oil on canvas 85 x 43 in. (216 x 109 cm.) Painted circa 1877 Provenance The artist, until his death in 1902. Mlle Jeanne Tissot, until her death in 1964; her sale, Château de Buillon, 8-9 Nov 1964. Private collection, Besancon. Anonymous sale; Christie's Monaco, 15 June 1986, lot 119. Private collection. Anonymous sale; Sotheby’s, London, 9 June 1993, lot 25. Purchased by the previous owner in 1994. Exhibited London, Grosvenor Gallery, East Gallery, 1877, no. 22. Thos Agnew & Sons Ltd, registered in England No 00267436 at 21 Bunhill Row, London EC1Y 8LP VAT Registration No 911 4479 34 THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com Literature: J. Ruskin, Fors Ciavigera Letter 79, E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), The Works of John Ruskin, Vol XXIX, p. 161. J. Laver, Vulgar Society - The Romantic Career of James Tissot, 1936, pp. 37-8, 69. W. E. Misfeldt, James Jacques Joseph Tissot: A Bibliocritical Study, Ann Arbor, University Microfilms 1971, pp. 168-70. M. Wentworth, James Tissot, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1984, pp. 136-8, 140, 141, 202. K. Matyjaskiewicz (Ed.), James Tissot (Catalogue to Exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, 1984-5), 1984, p. 115, no. 85. C. Wood, Tissot, 1986, p. -

Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915

Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915 Kimberly E. Hereford A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Susan Casteras, Chair Paul Berger Stuart Lingo Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art History ©Copyright 2015 Kimberly E. Hereford ii University of Washington Abstract Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915 Kimberly E. Hereford Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Susan Casteras Art History This dissertation examines representations in art of the Victorian woman in “altered states.” Though characterized in Victorian art in a number of ways, women are most commonly stereotyped as physically listless and mentally vacuous. The images examined show the Victorian female in a languid and at times reclining or supine pose in these representations. In addition, her demeanor implies both emotional and physical depletion, and there is both a pronounced abandonment of the physical and a collapsing effect, as if all mental faculties are withdrawing inward. Each chapter is dedicated to examining one of these distinct but interrelated types of femininity that flourished throughout British and American art from c. 1850 to c. 1910. The chapters for this dissertation are organized sequentially to demonstrate a selected progression of various states of consciousness, from the most obvious (the sleeping woman) to iii the more nuanced (the female Aesthete and the female medium). In each chapter, there is the visual perception of the Victorian woman as having access to otherworldly conditions of one form or another. -

Laurence Des Cars

Laurence des Cars (born in 1966) general heritage curator, was appointed President of the Public Establishment of the Musée d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie in March 2017 by the President of the French Republic, at the proposal of the Minister of Culture. From 1994 to 2007, Laurence des Cars was a curator at the musée d’Orsay, then from 2007 to 2014, she was Scientific Director of Agence France-Muséums, the French operator in charge of developing the Louvre Abu Dhabi. In January 2014, Laurence des Cars was appointed Director of the Musée de l’Orangerie. A specialist in 19 th and early 20 th century art, Laurence des Cars curated many exhibitions including Édouard Vuillard (Washington, National Gallery of Art; Montreal, Museum of Fine Arts; Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, London, Royal Academy of Art, 2003-2004); Gustave Courbet (Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Montpellier; Musée Fabre, 2007-2008); Jean-Léon Gérôme (Los Angeles, Getty Museum; Paris, Musée d’Orsay; Madrid, Museo Thyssen, 2010-2011); Louvre Abu Dhabi. Birth of a Museum (Paris, Musée du Louvre; Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Al Manarat, 2014); Sade. Attacking the Sun (Paris, Musée d’Orsay, 2014-2015); Apollinaire. The Eyes of the Poet (Paris, Musée de l’Orangerie, 2016). She published Nineteenth Century French Art (1819-1905) (Flammarion, 2006), edited by Henri Loyrette, former President-Director of the Musée du Louvre, and in collaboration with Sébastien Allard, Director of Paintings at the Musée du Louvre. She edited the book “Louvre Abu Dhabi, Birth of a Museum” (Flammarion, Musée du Louvre, 2013), and was one of the curators for the “Louvre Abu Dhabi, Birth of a Museum” exhibition presented at the Musée du Louvre from April to July 2014. -

The Tjhivbrsitt Op Oklahom Graduate College

THE TJHIVBRSITT OP OKLAHOM GRADUATE COLLEGE THE PRE-RAPHAELITES AHD THEIR CRITICS: A TENTATIVE APPROACH TOWARD THE AESTHETIC OP PRE-RAPHAELITISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY BY WILLIAM EVAN PREDEMAN Norman, Oklahoma _________ l â 5 6 __________ THE PEE-EAPHABLITBS AND THEIR CRITICS A TENTATIVE APPROACH TOWARD THE AESTHETIC OP PRE-RAPHAELITISM APPROVED BT Æ", ~hi. I DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PEBPAOE The purpose of this study is to exsimine the view points of a sufficient number of critics of the Pre- Eaphaelite Movement to arrive at a tentative definition and to place the movement in its proper historical per spective. The primary emphasis will be literary. But since ,the Pre-Raphaelite Movement began as a movement in painting and so expanded in its later phase that its influence spread to furniture making, interior decoration, tapestry and wall paper design, and book making and illustration, a completely literary study of the movement would be as inadequate as one dealing solely with the painting. Numerous studies have been made of the indi vidual Pre-Raphaelites and of the movement in general. Most of these, however, are devoted to relating biographi cal facts and to tracing the history of the movement. Critical studies of the aesthetic underlying the movement and motivating the individual members are few in number. Although Pre-Eaphaelitism is well documented, no universal agreement concerning the historical facts of the movement exists. Por this reason, the first part of the study is essentially historical, tracing the successive Phases through which Pre-Ranhaelitism progressed. -

BETTY CUNINGHAM GALLERY Jake Berthot Paintings and Drawings

BETTY CUNINGHAM GALLERY PRESS RELEASE IMMEDIATE RELEASE Jake Berthot Paintings and Drawings October 17- November 30, 2013 Opening Reception: Thursday, October 17, 6 – 8 PM “In an ugly time, Beauty is held in suspicion.” ~Jake Berthot, summer 2013 Betty Cuningham Gallery is pleased to announce an exhibition of new work by Jake Berthot including both paintings and drawings. This will be the artist’s fifth exhibition at the Gallery, located at 541 West 25th Street, New York, NY. The artist will be present for an opening reception on Thursday, October 17th, from 6 – 8 PM. Since the late 1960’s Jake Berthot has been known for his distinctive brushwork (an admirer of Milton Resnick), his characteristic softly-drawn line, his sensitive touch, his rich color, and his incorporation of the frame into his painting. These elements are found in his earlier, more formal, abstract work as well as in his recent subtle landscape paintings. The current exhibition includes approximately 16 paintings and 8 drawings, all completed in the last two years. Each painting or drawing, whether a broad landscape, a single tree or a still life, seem to coalesce into a single, deeply felt image. For example, in Coming Night and Ridge Line, both completed in 2013, a distant mountain emerges slowly in the light of a dark night space. Similarly, in Untitled (Tree), 2013 the tree which dominates the canvas comes into focus gradually from Berthot’s quiet touch. In the still-life, Table and Skull, 2012, the objects take form creating a poetic dialogue between object and paint. -

Les Préraphaélites, Modernistes Et Réactionnaires Muriel Pécastaing-Boissière Maître De Conférence En Civilisation Britannique À L’Université De Paris IV-Sorbonne

Les Préraphaélites, modernistes et réactionnaires Muriel Pécastaing-Boissière Maître de conférence en civilisation britannique à l’université de Paris IV-Sorbonne En septembre 1848, alors que l'Europe était en pleine effervescence révolutionnaire, sept jeunes gens farouchement opposés aux conventions de la Royal Academy de Londres fondèrent la Confrérie Préraphaélite. Parmi eux se trouvaient John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt et Dante Gabriel Rossetti, bientôt rejoints par William Morris et Edward Burne-Jones. Influencés par le Gothic Revival et les théories esthétiques de John Ruskin ainsi que par les réflexions morales et religieuses de leur temps, les Préraphaélites choisirent de renouveler la peinture britannique en s'inspirant d'un art médiéval idéalisé. Ils rejetèrent en effet l'enseignement de Raphaël et les règles de la représentation nées de la Renaissance pour leur préférer les primitifs italiens – d'où leur nom – et le naturalisme. Nous avons demandé à Muriel Pécastaing-Boissière en quoi ce mouvement qui semblait réactionnaire put scandaliser et bouleverser les milieux victoriens. Réalisme archaïsant et néogothique Dans les années 1830 et 1840, la peinture victorienne était fortement influencée par l'art du roman et les toiles narratives, moralisatrices et souvent mièvres de David Wilkie, William Mulready ou William Powell Frith rencontraient un immense succès. Prisonnier des conventions, répétitif et victime d'un enseignement académique, l'art pictural était dans l'impasse. Cependant, deux événements artistiques annoncèrent bientôt la révolte préraphaélite. Déjà, nombre d'artistes et d'intellectuels victoriens plaidaient pour un renouveau gothique, l'art médiéval étant perçu comme un modèle de sincérité et de liberté. Après l'incendie des Maisons du Parlement de 1834, le choix des peintres chargés de la réalisation des fresques intérieures fut confié à une commission présidée par le Prince Albert, d'origine germanique et grand collectionneur de Primitifs italiens. -

Jericho and the Pre-Raphaelites

1 Jericho and the Pre-Raphaelites John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shallot The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make. William Morris Few people are aware that the area of Oxford known as Jericho has a number of striking connections with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood which, as well as being the only British art movement to take on international significance, has claims to being the best-loved art movement of all. The Pre-Raphaelites' patron Thomas Combe, in company with his wife Martha, presided over what became a kind of "good-humoured salon" [Jon Whiteley, 'Oxford and the Pre-Raphaelites', Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1989, p. 26] in Jericho at the Combe's residence in Walton Street and the existence of this Jericho base led to the creation of a series of memorable paintings which were first of all painted, then hung and exhibited in Jericho. In 1850 Combe, who was then printer to the university, came across John Everett 2 Millais in Botley Wood where, together with Charles Collins - Wilkie's brother - he was engaged in painting. Combe took an interest in what they were both doing and invited them back to Jericho for lunch. Millais and Collins declined the invitation on the grounds that they were too busy. However, undeterred, Combe sent them over a hamper of food on his return and this was how the relationship began - one which would establish Jericho as a stamping-ground for Collins and Millais, later to be followed by other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. -

Laurence Des Cars Kaywin Feldman

Laurence Des Cars President, Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l'Orangerie, France English Laurence des Cars (born in 1966) general heritage curator, was appointed President of the Public Establishment of the Musée d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie in March 2017. A specialist in 19th and early 20th century art, Laurence des Cars was a curator at the Musée d’Orsay from 1994 to 2007; from 2007 to 2014, she was Scientific Director of Agence France-Muséums. In January 2014, Laurence des Cars was appointed Director of the Musée de l’Orangerie. She published Nineteenth Century French Art (1819-1905) (Flammarion, 2006), edited by Henri Loyrette and in collaboration with Sébastien Allard. She edited Louvre Abu Dhabi, Birth of a Museum (Flammarion, 2013), and was one of the curators for the “Louvre Abu Dhabi, Birth of a Museum” exhibition presented at the Musée du Louvre in 2014. Since 2017, Laurence des Cars has completely renewed and revitalised the world-class Impressionism and Post-Impressionism collections of the Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie, rolling out a programme of exhibitions, live shows and a new presentation of the works oriented towards all audiences, and open to the artists of today. Laurence des Cars is a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, Chevalier of the National Order of Merit and Officer of Arts and Letters. Kaywin Feldman Director, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA English Kaywin Feldman Director, National Gallery of Art Kaywin Feldman (b. 1966, Boston, MA, USA) has an MA in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, an MA in Museum Studies from the Institute of Archaeology at the University of London, and a BA, Summa cum laude, in Classical Archaeology from the University of Michigan. -

Chrétien De Troyes

Dossier de presse Septembre 2014 Chrétien de Troyes Yvain ou le Chevalier au Lion Lancelot ou le Chevalier de la Charrette illustrés par la peinture préraphaélite Traductions de Philippe Walter et de Daniel Poirion, Introductions de Philippe Walter et de Laurence des Cars. Une incarnation intense Sortieet poétique le 16 des octobre héros mythiques 2014 de la légende arthurienne par les peintres préraphaélites Parution le 16 octobre 2014 « Prêtez-moi le cœur et l’oreille car la parole se perd si le cœur ne l’entend pas. » Calogrenant dans Yvain ou le Chevalier au Lion Contact presse: Diane de Selliers, Éditeur Constance Tembremande 19 rue Bonaparte – 75006 Paris 00 33 (0)6 66 83 68 61 [email protected] www.editionsdianedeselliers.com 1 "Passé l'émerveillement esthétique, on perçoit combien toutes ces oeuvres regorgent de symboles, d'allégories, de réminiscences diffuses. Elles ouvrent une autre porte sur le rêve et la féerie, et rejoignent ainsi parfaitement les récits de Chrétien de Troyes." Diane de Selliers. 2 Fiche technique TITRE Yvain ou le Chevalier au Lion et Lancelot ou le Chevalier de la Charrette de Chrétien de Troyes illustrés pas la peinture préraphaélite AUTEUR Chrétien de Troyes DESCRIPTION L’intégralité de Yvain et Lancelot illustrés par les œuvres d’artistes préraphaélites. Les traductions en français moderne sont mises en valeur par une mise en forme inédite du texte, plus structurée et aérée, qui améliore la lisibilité. TRADUCTEURS Yvain, Philippe Walter, agrégé de lettres, médiéviste, spécialiste des mythologies chrétiennes – notamment de la littérature arthurienne – et de l'imaginaire médiéval. Lancelot, Daniel Poirion, agrégé de lettres, médiéviste, professeur à la Sorbonne puis directeur du programme des études médiévales de l'université de Yale (USA) jusqu’à sa mort en 1996.