Text Study the Season of Our Rejoicing?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elul Moon Journal 5781

High Holy Days 5782 Thi El Mo na ls o: High Holy Days 5782 Wel to Elu M or Elul is the last month of our Jewish calendar, the month when we transition from one year to the next. For generations, Jews across the world have spent this month of Elul reflecting on the previous year and thinking ahead to the new one. We invite you to do the same, and present the Elul Moon Journal! This journal invites folks of all ages to lean into the spiritual work of the High Holy Days season and 5782, the new year, with nightly journal prompts or discussion questions, and opportunities to track the moon’s progress through Elul. Journal one night, every night, or something in between. Resd to Pp n Tac t Mo Each evening of Elul corresponds to a page in this journal. The Hebrew dates you see on each page are the dates that begin at sundown those evenings. If the question stirs something in you, respond to it. If you find your pencil moving to a different beat, follow your heart. Feel free to incorporate a combination of writing and drawing. Our ancestors used the phases of the moon to track time. So too can we find meaning in centering ourselves around its waxing and waning. Before or aer your journal entry each night, hold up your paper to a window through which you can see the moon. Then trace it. Over the course of Elul, watch the skies and your journal pages as the moon grows from a sliver at the start to its full position by Rosh HaShanah. -

High Holy Day Information 5777 Table of Content

Congregation Neveh Shalom High Holy Day Information 5777 Table of content Rabbi Greeing..........................................................................................3 President Greeing....................................................................................4 Annual Giving Campaign...........................................................................5 Family Services Informaion...................................................................6-7 High Holy Day Schedule.........................................................................8-9 Registraion Form - detach and return.......................................Centerfold High Holiday Eiquete.............................................................................10 Of-Site Parking Map................................................................................11 Lifelong Learning................................................................................12-13 Sukkot......................................................................................................14 Simchat Torah Oktorahfest.......................................................................15 Page 2 Rabbi Greeting A contemporary sage has noted that ime is the medium of our lives and that we can be its arists. What she means is that the choices we make and the acts we undertake change both us and ime. That feels right, even though we don’t always catch that change as it happens. One day we wake up and look at the mirror from a slightly diferent angle, and we note the passage -

The Month of Elul (PDF)

Hear the Shofar! Daily Blasts During Elul Daily Sounding of the Shofar During the Hebrew month of Elul, we sound the shofar every day. These blasts are a “wake-up” call to our spirits, intended to inspire and remind us to engage in the soul searching needed to prepare for the High Holy Days. The sound is also significant as it brings our community together and elevates our Divine spirit. Beginning on the first day of Elul, August 9 and continuing until September 5, we will gather on Zoom every evening (except for Friday evenings, when the shofar will be heard during Shabbat services) at 6:00 pm for a brief message for reflection and to hear the shofar. On Saturdays, we will begin with Havdalah. Please join us on Zoom (no prior registration needed). We will start at 6:00, and the Shofar will be sounded at about 6:05. You may drop in early to shmooze if you wish. Click here to join every evening at 6:00pm! We also invite everyone to help sound the shofar during these gatherings! There are 24 opportunities. If you or a member of your family would like to blow the shofar for us, please contact Lisa Feldman. Daily Emails During the Month of Elul Once again, Ritual Committee members have curated a series of brief readings on the themes of the High Holy Days season. Sign up to receive a short, daily email posing ideas and questions for reflection about the themes of the Days of Awe. Subscriptions were automatically renewed, but if this is new to you, you can subscribe directly in ShulCloud or by sending an email to [email protected]. -

2021/5781 High Holy Days WORSHIP INFORMATON ~

2021/5781 High Holy Days WORSHIP INFORMATON ~ Rosh HaShanah ~ S’lichot Service jointly w/ Ohavi Saturday September 12 8:00pm Zedek ~ Erev Rosh HaShanah Service Friday September 18 6:30pm ~ Morning Children’s Service Saturday September 19 9:00am ~ Morning Rosh HaShanah Service Saturday September 19 10:00am ~ Tashlich (location TBA) Saturday September 19 4:00pm ~ Insomniac Lounge: alternative Rosh Hashanah Service Saturday September 19 10:00pm Between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur ~ Shofar Drive-thru Sunday September 20 11:00am ~ JCVT Vermont Shabbat Shuva Friday September 25 TBD Service ~ Insomniac Lounge: Shabbat Shuva Friday September 25 10:00pm meditation service ~ Shabbat Shuva Morning Service Saturday September 26 9:30am ~ Shabbat Shuva Torah Study Saturday September 26 10:30am Yom Kippur ~ Kol Nidre/Erev Yom Kippur Sunday September 27 6:30pm ~ Morning Children’s Service Monday September 28 9:00am ~ Morning Yom Kippur Service Monday September 28 10:00am ~ Yizkor Service Monday September 28 2:00pm ~ Making Prayer Real: Engaging Yom Kippur Monday September 28 3:00 pm ~ Minchah Service Monday September 28 4:30pm ~ Neilah Monday September 28 6:00pm ~ Break Fast Monday September 28 7:00pm Join us on ZOOM This year's High Holy Day services will be a different experience to what we are used to. Our services will be led by our rabbi, David Edleson, and our cantor Mark Leopold. Due to the pandemic and the significantly heightened risks of singing in closed spaces, we will not be celebrating in the Sanctuary but will continue our worship on ZOOM as we have been every Shabbat. -

![[Answers.] 1. True Or False: Purim Is a Major Jewish Holiday. [False](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8558/answers-1-true-or-false-purim-is-a-major-jewish-holiday-false-808558.webp)

[Answers.] 1. True Or False: Purim Is a Major Jewish Holiday. [False

PURIM TRIVIA GAME* [Answers.] 1. True or False: Purim is a major Jewish holiday. [False. It is not mentioned in the Five Books of Moses or Torah. The High Holy Days, Passover and Festivals are considered major holidays.] 2. True or False: Purim is celebrated everywhere only on one day in the Hebrew month of Adar? [False. Purim is celebrated on 14th day of Adar in most places, but in Jerusalem and other walled cities (like Shuhsan of ancient Persia where it originated) it is celebrated on the 15th of Adar since the news of the Jews victory took longer to get dispersed to outlying areas.] 3. True or False: The name Purim is derived from a Hebrew word whose plural form means “lots” relating to a kind of lottery drawing. [True. It derives also from Aramaic for “a small smooth object” tossed to determine a winner. It is thought that Haman used a random drawing to select the day on which the Jews were to be annihilated.] 4. True or False: This holiday originated with an historic event in the 5th century BCE in the ancient land of Israel. [False. It originated with an event circa the 5th century in Shushan, Persia, today known as Iran.] 5. Why is the name of G-d not mentioned even once in the entire Book of Esther from which Purim originated? [Since the original was written in the form of a scrolled letter sent to the far off areas of the Kingdom to describe the reason for celebration, it was open to great risks of being mishandled or desecrated. -

Hilkhot Yom Kippur 5779

Hilkhot Yom Kippur 5779 Rabbi Isaac Attia Co-Director, JLIC at Brandeis [email protected] Zmanim are applicable for Waltham, MA Fast begins before 6:49p1 Candle Lighting 6:31p Kol Nidre and Ma’ariv 6:25p Shacharit 8:15a Yizkor ~11:00a YK Afternoon Shiur ~4:10p Mincha 5:10p Neila 6:20p Havdallah/Fast Ends 7:30p All davening will take place in the Sherman Function Hall Anyone with a medical condition that makes fasting difficult should consult with Rav Isaac or your personal halakhic authority for advice. Similarly, anyone who takes prescription medication for a serious medical condition should consult with their rabbi for advice on what to do. Erev Yom Kippur (Tuesday September 17) Asking for forgiveness - Yom Kippur is a day to seek forgiveness from G-d for our offenses against Him. But G-d will not forgive our sins until we seek forgiveness from our fellows.2 At the same time, one should be quick to forgive.3 This can be a humbling and worthwhile experience.4 Teshuva - Before we can discuss the rituals of the day, we must remember the whole point: to regret our sins and return to G-d. One should carve out some alone time in the week and days preceding Yom Kippur for some genuine soul-searching about the past year and some constructive imagination of what an ideal upcoming year should look like. Hatarat Nedarim – Anyone who has not yet said hatarat nedarim (annulment of vows) 1 NOTE: There is a Biblical mitzvah to “add” to your fast by beginning your fast early. -

High Holy Days

5781 HIGH HOLY DAYS SEPTEMBER 18–28, 2020 Dear Friends, Shanah Tovah! Sitting at Sacred Heart last year, celebrating together, I doubt that anyone could have imagined, let alone predicted, the situation we find ourselves in this year. More than once in recent months, someone has said to me, “if this was a novel, we would have criticized it as unbelievable.” Yet deep within our Jewish celebration of the new year is an awareness of the tenuousness of life, of our reality as ephemeral beings, of the uncertainty with which we face each day. Our prayers proclaim this awesome and frightening reality as we contemplate the possibilities that might confront us. Over these holy days, we celebrate and we mourn, we consider where we have missed the mark, and reflect on what is most important to us, what we would want to do if we knew our time was short. This year there is a somber aspect to the new year, but that should not overshadow its sweetness. This year’s realization that “anything can happen” worries us, but we shouldn’t lose sight of its promise; anything can happen, so we can’t give up. New babies, new reconciliations, hopes and dreams fulfilled, these too are possible. Nehemiah reassured the people on a Rosh HaShanah 2,500 years ago telling them “not to weep…but to eat and drink things that are sweet and delicious and share with those who have nothing.” As have generations of Jews before us, in their own times of trouble and of joy, we pray: May the old year with its curses be ended, may the new year with its promise begin. -

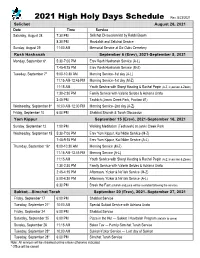

2021 High Holy Days Schedule Rev. 8/23/2021

2021 High Holy Days Schedule Rev. 8/23/2021 Selichot August 28, 2021 Date Time Service Saturday, August 28 7:30 PM Selichot Discussion led by Rabbi Bloom 8:30 PM Havdalah and Selichot Service Sunday, August 29 11:00 AM Memorial Service at Six Oaks Cemetery Rosh Hashanah September 6 (Erev), 2021-September 8, 2021 Monday, September 6* 5:30-7:00 PM Erev Rosh Hashanah Service (A-L) 7:45-9:15 PM Erev Rosh Hashanah Service (M-Z) Tuesday, September 7* 9:00-10:30 AM Morning Service–1st day (A-L) 11:15 AM-12:45 PM Morning Service–1st day (M-Z) 11:15 AM Youth Service with Sheryl Keating & Rachel Pepin (A-Z, in-person & Zoom) 1:30-2:30 PM Family Service with Valerie Seldes & Adriana Urato 2:45 PM Tashlich (Jarvis Creek Park, Pavilion #1) Wednesday, September 8* 10:00 AM-12:00 PM Morning Service–2nd day (A-Z) Friday, September 10 6:00 PM Shabbat Shuvah & Torah Discussion Yom Kippur September 15 (Erev), 2021-September 16, 2021 Sunday, September 12 1:00 PM Walking Meditation (Teshuvah) at Jarvis Creek Park Wednesday, September 15 5:30-7:00 PM Erev Yom Kippur, Kol Nidre Service (M-Z) 7:45-9:15 PM Erev Yom Kippur, Kol Nidre Service (A-L) Thursday, September 16* 9:00-10:30 AM Morning Service (M-Z) 11:15 AM-12:45 PM Morning Service (A-L) 11:15 AM Youth Service with Sheryl Keating & Rachel Pepin (A-Z, in-person & Zoom) 1:30-2:30 PM Family Service with Valerie Seldes & Adriana Urato 2:45-4:15 PM Afternoon, Yizkor & Ne’ilah Service (M-Z) 5:00-6:30 PM Afternoon, Yizkor & Ne’ilah Service (A-L) 6:30 PM Break the Fast (challah and juice will be available following -

Temple House of Israel Bulletin

Temple House of Israel Bulletin A Member Congregation of the Union for Reform Judaism 15 North Market Street, Staunton, VA 24401 (540) 886-4091 Mailing Address: P.O. Box 1412, Staunton, VA 24402 www.thoi.org The Calendar Our mission is to perpetuate Jewish life and identity through a welcoming community of spirituality, learning, service, joy and worship October 2016 / Elul 5776 –Tishrei 5777 Dear Temple House of Israel, President’s We are swiftly advancing on October, which is our busiest month this year because of the high holidays. This year we welcome Rabbi Joel Schwartzman who will play opposite Rabbi Joe to accommodate both congregations. Rabbi Joel will be with us on Erev Rosh Hashanah and on Message Yom Kippur day. Please introduce yourself at the Erev Rosh Hashanah dinner on October 2 at 6 pm, organized by the Women’s Group. It is a meat meal; therefore, remember not to bring dishes that contain milk products. Also, please bring a dessert to share for afterward. As you remember, this is the holiday season that encourages us to assess our behavior of the last year and to ask forgiveness for our failings. For some of us, that is a massive job. I had better get started! We have a new Gaspack heat and air conditioning unit for the social hall. Enjoy the temperature and consider writing a check to the building fund to defray its cost. Your contribution to the fund will be matched by an anonymous donor. What a deal! We send continuing thanks to the donor who is chipping in until the end of 2016. -

Five-Year Calendar of Major Jewish Holidays

FIVE-YEAR CALENDAR OF MAJOR JEWISH HOLIDAYS This calendar has been prepared to assist you in scheduling business, school, or community events. For schools, this includes scheduling with an equity lens regarding major assignments, examinations, assemblies, field trips and graduations, as well as school-related programs for parents. Courts, legislative bodies and administrative agencies may also find the calendar helpful in avoiding scheduling conflicts. An asterisk (*) denotes the Jewish High Holy Days and major Biblical festivals in observance of which labor is traditionally prohibited. As a result, Jewish individuals may be absent from both work and school. Please note that Jewish holidays begin at sunset on the evening the day before listed on calendars for the holiday. The Jewish Sabbath begins at sunset on Friday of each week and lasts until nightfall on Saturday. So as not to penalize students or workers for their religious observance, we ask that scheduling of events, tests, preparation for exams, assignments, assemblies, sports events, etc. on Jewish holidays, the Jewish Sabbath be avoided, or if such dates cannot be avoided, that consideration be given to the affected Jewish persons for reasonable opportunity for makeups. HOLIDAY 2020-2021 2021-2022 2022-2023 2023-2024 2024-2025 Rosh Hashanah* Sep. 19-20 Sep. 7-8 Sep. 26-27 Sep. 16-17 Oct. 3-4 (New Year) Sat-Sun Tues-Wed Mon-Tues Sat-Sun Thurs-Fri Yom Kippur* Sep. 28 Sep. 16 Oct. 5 Sep. 25 Oct 12 (Day of Atonement) Mon Thurs Wed Mon Sat Sukkot* Oct. 3-4 Sep. 21-22 Oct. 10-11 Sep. -

High Holy Days Q&A Full Sheet.Indd

The High Holy Days Questions and Answers to help you more fully experience and enjoy these Holy Days What do the words Rosh Hashanah mean? Rosh Hashanah is Hebrew for “head of the year” (literally) or “beginning of the year” (figuratively). In the Torah, we read, “In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, there shall be a sacred assembly, a cessation from work, a day of commemoration proclaimed by the sound of the Shofar.” Therefore, we celebrate Rosh Hashanah on the first and second days of Tishrei, the seventh month of the Jewish calendar. Why is the New Year in the Fall? Why do we start the New Year in the seventh month? Our ancestors had several dates in the calendar marking the beginning of important seasons of the year. The first month of the Hebrew calendar was Nisan, in the spring. The fifteenth day of the month of Shevat was considered the New Year of the Trees. But the first of Tishrei was the beginning of the economic year, when the old harvest year ended and the new one began. Around the month of Tishrei, the first rains came in the Land of Israel, and the soil was plowed for the winter grain. Eventually, the first of Tishrei became not only the beginning of the economic year, but the beginning of the spiritual year as well. What are the “Days of Awe?” Rosh Hashanah is the first of the “High Holy Days,” and begins the most spiritually intense part of the Jewish year – the yamin nora’im, the Days of Awe. -

The Yomim Nora'im, Days of Awe Or High Holy Days, Are Among

The Yomim Nora’im, Days of Awe or High Holy Days, are among the most sacred times in the Jewish calendar. The period from Rosh HaShanah through Yom Kippur encompasses a time for reflection and renewal for Jews, both as individuals and as a community. In addition, throughout the world, and especially in American Jewish life, more Jews will attend services during these days than any other time of the year. The High Holy Days fall at a particularly important time for Jewish students on college campuses. Coming at the beginning of the academic year, they will often be a new student’s first introduction to the Jewish community on campus. Those students who have a positive experience are likely to consider attending another event or service, while those who do not feel comfortable or welcomed will likely not return again. Therefore, it is critical that both services and other events around the holidays be planned with a great deal of care and forethought. This packet is designed as a “how-to” guide for creating a positive, Reform High Holy Day experience on campus. It includes service outlines, program suggestions and materials, and sample text studies for leaders and participants. There are materials and suggestions for campuses of many varieties, including those which have separate Reform services – either led solely or in part by students – and those which only have one “communal” service. The program ideas include ways to help get people involved in the Jewish community during this time period whether or not they stay on campus for the holidays.