Public Records and the Archival Logics of the Oroville Dam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION Divisions of Boating and Waterways, Historic Preservation and Off-Highway Vehicles News Release For Immediate Release Contact: Apr. 5, 2017 Aaron Wright Sector Superintendent [email protected] (530) 538-2200 Summer Recreation at Lake Oroville State Recreation Area OROVILLE, Calif. -- The emergency effort to repair the Lake Oroville spillways will not interfere with most outdoor recreation this summer at the lake, and with the exception of the Spillway Boat Launch Ramp, all boat launch ramps are open, announced California State Parks (DPR) and the Department of Water Resources. All campgrounds also are open and floating campsites are back on the lake and available for rental. Some areas near the dam will continue to be off-limits to visitors as crews work to repair or replace spillways damaged in February during high runoff. Outdoor activities available at Lake Oroville this summer include: Campgrounds: All campgrounds are now open with site-specific reservations available at Bidwell Canyon, Loafer Creek and Lime Saddle. Campers without reservations are still welcome on a day-to-day basis to any campsites that have not been previously reserved. Campground showers have been equipped with token machines. Each site will have a unique, collectable token which can also be used at other participating state parks. Trails: Lake Oroville has a number of trails for hiking, biking and equestrian use. Trails around the Diversion Pool and Hyatt Power Plant likely will be closed throughout the summer, although DPR may make changes to other trails to accommodate more hikers and help compensate for the closures. -

Insights Into the Oroville Dam 2017 Spillway Incident

geosciences Communication Insights into the Oroville Dam 2017 Spillway Incident Aristotelis Koskinas 1, Aristoteles Tegos 1,2,*, Penelope Tsira 1, Panayiotis Dimitriadis 1 , Theano Iliopoulou 1, Panos Papanicolaou 1, Demetris Koutsoyiannis 1 and Tracey Williamson 3 1 Department of Water Resources and Environmental Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Heroon Polytechniou 9, Zografou, GR-15780 Zographou Athens, Greece; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (P.T.); [email protected] (P.D.); [email protected] (T.I.); [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (D.K.) 2 Arup Group Limited, 50 Ringsend Rd, Grand Canal Dock, D04 T6X0 Dublin 4, Ireland 3 Arup, 4 Pierhead Street, Cardiff CF10 4QP, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 December 2018; Accepted: 7 January 2019; Published: 11 January 2019 Abstract: In February 2017, a failure occurring in Oroville Dam’s main spillway risked causing severe damages downstream. A unique aspect of this incident was the fact that it happened during a flood scenario well within its design and operational procedures, prompting research into its causes and determining methods to prevent similar events from reoccurring. In this study, a hydroclimatic analysis of Oroville Dam’s catchment is conducted, along with a review of related design and operational manuals. The data available allows for the comparison of older flood-frequency analyses to new alternative methods proposed in this paper and relevant literature. Based on summary characteristics -

April 21, 2021

ITEM NO. 15d ORIGINATING SECTION: Integrated Planning CONTACT: Sal Segura/Amparo Flores AGENDA DATE: August 18, 2021 SUBJECT: Monthly Water Inventory and Water Budget Update SUMMARY: In support of Zone 7’s mission to “deliver safe, reliable, efficient, and sustainable water…services,” for Strategic Plan Goal A – “Reliable Water Supply and Infrastructure;” this report summarizes water supply, usage and storage conditions as of the end of July 2021. An overall analysis of the annual water supply takes place in April of each year with the Annual Review of Sustainable Water Supply. Long-term water supply planning is summarized in the Urban Water Management Plan, which is updated every five years and assesses water supply reliability on a 20-year horizon. The report considers the various sources of supply and storage available to Zone 7 locally and in State Water Project facilities, as well as in remote groundwater storage banks. Figure ES 1: At-a-Glance Summaries of Water Supplies, Deliveries, and Available Water (as of July 2021) Annual Yield: Imported and Local Water Supplies vs. Delivered Water Year-To- 400,000 50,000 Date Yield 300,000 feet) - 0 Annual Imported Local Average feet - (acre 200,000 Annual Yield Water Water Yield acre Water Deliveries: 100,000 2021 feet) - 10,000 0 5,000 2013 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 (acre 0 Water Deliveries Total Water Treated Untreated 2021 Projected Deliveries Delivered Water Water Actual Water Deliveries Water Storage Treated Water Deliveries: Treated Water Deliveries: Imported Water (via Delta) 11% 0% Surface Water 43% Local Water (Lake Del Valle) Groundwater 57% Imported Water (Stored As Groundwater) 89% JULY 2021 Zone 7 Water Inventory and Water Budget Supply and Demand (See Table 1, Table 2, Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4) • Monthly totals: 5,150 AF delivered to customers (4,150 AF treated, 1,000 AF untreated) • The total treated water production increased by 6% compared to last month. -

CA-Waterways-Map.Pdf

O R E G O N S rk m o it F h e dl R Mid . Goose Lake S o ut k h r o F C K l O O a m a N t h r Sa e c v r er i a Riv R m d e u A A aterways n o l t o o C c R W M E V A D i v e R i r r t v i e Some of the water you use every day has probably traveled T P r S S r i n i Trinity Lake ty M a d T T R iv er great distances and over high mountain ranges before reaching E UREKA R i v e r Shasta Lake Va n your faucet. This is because water is not always where we need R EDDING Du Clear zen Whiskeytown River Creek Lake Tunnel it. In California, most of the rain and snowfall is in the north. But Lake Antelope E Almanor Lake e l most of the people live in the south. The solution is to distribute S a R c i v r e a r m Corning R k Lake Frenchman e r n o Canal F Davis Lake the water to where it is needed through delivery systems such t o h t r o A R N rk Black i Fo v e e Butte r dl id as the State Water Project (SWP). Lake M Lake k N or F Oroville h t u So G Thermalito New Bullards The SWP delivers water from Lake Oroville in the north to the T Forebay and Bar Reservoir e h Lake Oroville Afterbay F e a a Visitors Center Indian m t h r a a e Valley e iv E R R r a San Francisco Bay area, the San Joaquin Valley, and Southern b u u Y Reservoir - s s i Clear Lake R a C i n o v e l u r S R sa i California. -

Federal Register/Vol. 73, No. 75/Thursday, April 17, 2008/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 73, No. 75 / Thursday, April 17, 2008 / Notices 20937 The determination that this item is an evidence, to have been removed from a Department of Parks and Recreation unassociated funerary object is based on specific burial site of a Native American Committee on Repatriation and museum documentation, consultation individual. Officials of the American professional staff in consultation with information provided by the tribe and Museum of Natural History also have representatives of Mechoopda Indian expert opinion. Though museum determined that, pursuant to 25 U.S.C. Tribe of Chico Rancheria, California; documentation does not specifically 3001(2), there is a relationship of shared Round Valley Indian Tribes of the indicate that this cultural item was group identity that can be reasonably Round Valley Reservation, California; associated with a burial, the condition traced between the unassociated and United Maidu Nation, a non- of the item and its type are consistent funerary objects and the Caddo Nation federally recognized Indian group. The with a funerary context. Based on of Oklahoma. Berry Creek Rancheria of Maidu Indians ceramic style, this cultural item dates to Representatives of any other Indian of California; Enterprise Rancheria of between CE 1500 and 1750. Historical tribe that believes itself to be culturally Maidu Indians of California; and and archeological evidence indicates affiliated with the unassociated funerary Mooretown Rancheria of Maidu Indians that the Ouachita River valley region objects should contact Nell Murphy, of California were contacted to was occupied by the Caddo during the Director of Cultural Resources, participate in the consultations. historic period, and that this group American Museum of Natural History, In February and April of 1963, human emerged from pre-contact Caddoan Central Park West at 79th Street, New remains representing a minimum of 25 culture dating back to approximately CE York, NY 10024, telephone (212) 769– individuals were removed from the 850. -

The San Luis Reservoir, One of the Largest in California, Stores Water

SAN LUIS RESERVOIR The San Luis Reservoir, one of the largest in California, stores water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and sends it by aqueduct to the Bay Area and Southern California. In midsummer, it held about 20 percent capacity. 74 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE SEP 2014 RUN DRY AFTER THREE HISTORICALLY DRY YEARS, CALIFORNIA’S DROUGHT GROWS MORE CONFOUNDING AND THE FUTURE OF ITS WATER SUPPLY MORE UNCERTAIN. BY BILL MARKEN, HONORARY ASLA PHOTOGRAPHY BY PETER BENNETT/GREEN STOCK PHOTOS LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE SEP 2014 / 75 O TALK ABOUT DROUGHT IN CALIFORNIA, YOU COULD START WITH THE MID-HOLOCENE PERIOD, WHEN A 1,400-YEAR DROUGHT LOWERED LAKE TAHOE 20 FEET AND LASTED LONG ENOUGH FOR CONIFERS TO GROW THREE FEET THICK ABOVE THE RECEDING WATERLINE before the lake eventually rose back up water. One spokesperson for a water At my neighborhood market in the over them. Or with the 1930s, when agency said, “We’re technically not in heart of Silicon Valley, Jim the butch- farm families escaped the Dust Bowl a drought”—that agency had enough er told me why the price of lamb has of Texas and Oklahoma and ran up water. Another agency said, “The dis- skyrocketed—rack of lamb, bones, T OPPOSITE against a California dry spell nearly as trict could run out of water by July.” fat, and all, sells for $29 a pound. devastating. Or start with 1976–1977, An operator of sled dog teams in the He said, “We usually get our lamb Water from Northern then the driest rainy season recorded, Sierra has gone out of business from from the Central Valley, where the California is sent south to Los Angeles by way when drastic water-saving measures a lack of snow, and a Modesto golf sheep graze on winter grass. -

California's Water Conditions and the Importance of Lake Oroville

Issues By Ken Melban Watch Vice President of Industry Affairs California’s Water Conditions and the Importance of Lake Oroville agency water or pump that nearly 43 percent was considered water from their own Extreme to Exceptional drought, in- wells. cluding almost all avocado producing Due to the strong areas. Now, in just three months, none atmospheric river con- of California is in Extreme or Excep- ditions over the last tional drought conditions, with almost few months, most res- 62 percent of California now complete- ervoirs throughout ly out of the drought. California are close to Most avocado growing regions capacity, aquifers are remain in Moderate to Severe drought slowly being recharged conditions, but that’s a major improve- and snow pack lev- ment from November, 2016. At the els are nearing record time of this writing a significant series depths. This is obvi- of storms have just made their way ously great news for through California resulting in very California. However, heavy rainfalls in the areas of Santa Bar- water-related challeng- bara and Ventura Counties. A total of es remain in specific 7.6 inches of rainfall was recorded at the areas of the state, and California Avocado Commission’s Pine some are more obvious Tree Ranch in Ventura County during than others. the period of February 17 – 20. This California’s Water Conditions The U.S. Drought Monitor for is great news and these storms, as evi- With California’s 2017 hydrologi- California (box to the left) provides a denced by the Drought Monitor, have cal conditions off to a historic start, al- very compelling illustration of how rap- significantly improved the hydrologi- most all avocado growers have received idly California’s drought conditions have cal conditions within those two coun- a long overdue break from irrigation improved. -

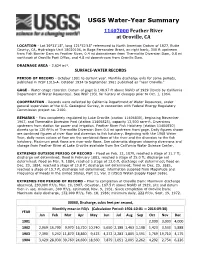

USGS Water-Year Summary

USGS Water-Year Summary 11407000 Feather River at Oroville, CA LOCATION - Lat 39°31'18", long 121°32'48" referenced to North American Datum of 1927, Butte County, CA, Hydrologic Unit 18020106, in Boga Fernandez Grant, on right bank, 300 ft upstream from Fish Barrier Dam on Feather River, 0.4 mi downstream from Thermalito Diversion Dam, 0.8 mi northeast of Oroville Post Office, and 4.8 mi downstream from Oroville Dam. DRAINAGE AREA - 3,624 mi². SURFACE‐WATER RECORDS PERIOD OF RECORD - October 1901 to current year. Monthly discharge only for some periods, published in WSP 1315-A. October 1934 to September 1961 published as "near Oroville." GAGE - Water-stage recorder. Datum of gage is 148.97 ft above NGVD of 1929 (levels by California Department of Water Resources). See WSP 1931 for history of changes prior to Oct. 1, 1964. COOPERATION - Records were collected by California Department of Water Resources, under general supervision of the U.S. Geological Survey, in connection with Federal Energy Regulatory Commission project no. 2100. REMARKS - Flow completely regulated by Lake Oroville (station 11406800), beginning November 1967, and Thermalito Diversion Pool (station 11406825), capacity 13,500 acre-ft. Diversions upstream from station for power and irrigation. Feather River Fish Hatchery (station 11406930) diverts up to 120 ft³/s at Thermalito Diversion Dam 0.4 mi upstream from gage. Daily figures shown are combined figures of river flow and diversion to fish hatchery. Beginning with the 1968 Water Year, daily mean values of flow are the combined flows of the river and the diversion to the fish hatchery. -

Drought Brochure 2021 Update

Drought In California January 2021 California Department of Water Resources | Natural Resources Agency | State of California Major Water Facilities Tule Lake Clear LLaakke Reservoir Trinity Reservoir Shasta Lake Whiskeytown Redding State Water Project Lake Antelope Federal Water Project Corning Canal Lake Tehama-ColuColussa Local Water Project Canal Frenchmmaan BlackBlack ButteButte LaLakke Lake Lake Lake Oroville Davis Stony GoGorgege Reservvoioir New BullBullaards East PaParrk Reservoivoir Bar Reservoir Lake Mennddoocincino Englebrightight Reservoivoir Indian Vaalleylley Reservoivoir Glenn-Colusa Canal Lake Sonoma Folsom Lake Lake Sacramento Auburn FolFolsom Sooututhh CCananaal Berryessa Putah S. CanaCanal Camanche Reservvoioir North Bay Aqueduct Mokelkeluummnne New Hogan Reservoir AqAquedueducuct New Meloelonnees LaLakke Contra Costa CCananal Stockton Los Vaqueros Reservoir Hetch Hetchyetchy Reservoir Don Pedro Lake San Francisco Lake McClure Lake Crowley Lake Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct Del Vaalllle South Bay Aqueduceduct Delta-Meendotandota Pachechecoo Conduit Canal Madera CaCanal Tinemaha Santa Clara CondConduiuit Millerton Lake Reservoir Hollister Condduuiit Pine Flat Reservoir San Luis Reeservvoioir Fresno San Luis Los Banos Reservoir Canal Lake Friant-Kern Kaweah Coalinga Canal Canal Haiwee Reservoir Lake Calif Success San Antonio Reservvoioir or Nacimientnto ni Isabella Reservoiir a Lake Los Angeles Cross Valley Aqueduct Canal California Aqueduct Twitchelwitchell Coastal Branch Reservoir Quail Lake Aq ued Pyramid LaLakke u ct Colorado -

11407000 Feather River at Oroville, CA Sacramento River Basin

Water-Data Report 2011 11407000 Feather River at Oroville, CA Sacramento River Basin LOCATION.--Lat 39°31′18″, long 121°32′48″ referenced to North American Datum of 1927, Butte County, CA, Hydrologic Unit 18020106, in Boga Fernandez Grant, on right bank, 300 ft upstream from Fish Barrier Dam on Feather River, 0.4 mi downstream from Thermalito Diversion Dam, 0.8 mi northeast of Oroville Post Office, and 4.8 mi downstream from Oroville Dam. DRAINAGE AREA.--3,624 mi². SURFACE-WATER RECORDS PERIOD OF RECORD.--October 1901 to current year. Monthly discharge only for some periods, published in WSP 1315-A. October 1934 to September 1961 published as "near Oroville." CHEMICAL DATA: Water years 1906-07, 1951-77. SPECIFIC CONDUCTANCE: Water years 1972-78. WATER TEMPERATURE: Water years 1954-92. SEDIMENT DATA: Water years 1957-79. REVISED RECORDS.--WSP 843: 1907 (instantaneous maximum discharge), 1909 (instantaneous maximum discharge), 1914-15 (instantaneous maximum discharge), 1919 (instantaneous maximum discharge), 1927-28 (instantaneous maximum discharge). WSP 881: 1913-28 (yearly summaries). WSP 1515: 1906-8. WSP 1931: Drainage area. WDR CA-74-2: 1968-70 (adjusted monthly discharge), WDR US-2007: 2006 (adjusted monthly discharge), WDR US-2008: 2007 (adjusted monthly discharge). GAGE.--Water-stage recorder. Datum of gage is 148.97 ft above NGVD of 1929 (levels by California Department of Water Resources). See WSP 1931 for history of changes prior to Oct. 1, 1964. COOPERATION.--Records were collected by California Department of Water Resources, under general supervision of the U.S. Geological Survey, in connection with Federal Energy Regulatory Commission project no. -

Lake Oroville Spillway Incident: Timeline of Major Events February

Lake Oroville Spillway Incident: Timeline of Major Events February 4-25 Oroville Spillway Public Info Line: (530) 538-7826 ➊ February 7: As water releases from the flood February ➊ control spillway ramp up to 54,500 cubic feet per 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 second (cfs), in anticipation of inflows expected from rainfall, DWR employees notice an unusual Cubic feet per second (cfs) Inflows to Lake Oroville reach flow pattern. Spillway flows stop for investigation. 180,000 190,435 cfs, significantly Engineers find large area of concrete erosion. Between higher than forecasted ➋ February 8: DWR begins ongoing consultation with February 6-10, FERC and other dam safety agencies. DWR runs test 12.8 inches of rain Mandatory Flood Control flows down the damaged spillway, monitoring further 160,000 fall in the Feather Spillway erosion, and prepares for possible use of emergency River Basin evacuation outflows raised spillway. 24/7 emergency interagency operations order is to 100,000 cfs to centers activate to study and implement response issued ease pressure to flood control spillway and related structures, with 140,000 ➍ on Emergency ➋ ➌ careful study of weather forecasts. Spillway ➌ February 11: Inflow to Lake Oroville brings lake ➍ level above 901 feet. This engages the emergency 120,000 spillway for the first time in the history of the facility. ➍ February 12: Anticipated erosion begins to progress faster than expected at the base of the emergency ➐ spillway. The Butte County Sheriff’s Office issues 100,000 mandatory evacuation orders for the Oroville area. -

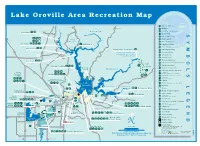

Lake Oroville Area Recreation Map T R N E E S O M T U R R Bike Trail/40 Mile Loop C a to Quincy

WATE OF R Lake Oroville Area Recreation Map T R N E E S O M T U R R Bike Trail/40 mile loop C A To Quincy P To Quincy Boating E D a r k E S Paradise P e n Boat/Car Top Access North Fork D Nelson Bar CT B= Pearson Rd. SYMBOLS LEGEND t z Boat House C a n yon Boating/No Power NP R o a d S 78? West T Boat Launch To Chico A 70 A I Branch BIC Boat-In-Camping Ac CS N Nelson T Bar Lime Saddle CT Dark Canyon CampfireE Center R =9@M Road B O FO CampgroundF LI CA Vinton Gulch CT Lime = F B= Saddle Feather Falls and Overlook Camping/Floating Road 1 99 = 640 feet high and sixth highest Camping/Group 191 Rd. R d 162 waterfall in the U.S. is located Pentz Butte Durham- Vinton Concessions College Gulch Rd. Hwy. in Plumas National Forest Durham-Dayton Hwy. C Durham-Pentz Rd. Dump Station h e r E Enroute Camping o Goat Ranch BIC k 7= e 9 mile Equestrian Trail/17.5 mile loop e Quincy EC 70 = trail Equestrian Camp Bloomer Primitive BIC (roundtrip) Road M CS 78= Foreman Fish Cleaning Station Creek Middle Fork Hatchery Self-Guided Tour Rd. E Olive M North 149 DWR HEADQUARTERS A > CS HQ Department of Water Resources, 460 Glen Drive Thermalito Spillway DPR HEADQUARTERS Forebay 9=:@ 7 HQ Department of Parks and Recreation, 400 Glen Drive BIC ] DFG HEADQUARTERS HQ Department of Fish and Game 7 F F NP BH Table = ABB Diversion Pool (Day-Use & Seasonal Only) CT 7 7 Hiking E B Lumpkin >9=C F = NP Lake Hunting (check with Dept.