Levels of Competitive and Cooperative Play in Dyadic Game Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Research on Civil Engineering Students' Past Video Game Playing

Journal of Engineering Research and Applied Science Available at www.journaleras.com Volume 4 (2), December 2015, pp 296-302 ISSN 2147-3471 © 2015 A research on civil engineering students’ past video game playing experiences S.A.Yildizel1, G.Kaplan2, E.Dogan1, Y.Arslan3,a, A.U.Ozturk1 1Celal Bayar University, Civil Engineering, Manisa, Turkey. 2Kastamonu University, Duzce Vocational Schools, Kastamonu, Turkey. 3Duzce University, Duzce Vocational Schools, Duzce, Turkey. Accepted 05 September 2015 Abstract Within the scope of this paper, past video game playing experiences of civil engineering students is investigated in order to identify the most preferred video game classifications that were played as an engineer candidate and its contribution to their education. A questionnaire practice is chosen and questions are randomly distributed to the civil engineering students. This technique is applied to 200 civil engineer candidates to figure out their past video game preferences before becoming a member of civil engineering department. The analysis of the questionnaire results indicates that the top three game classes in the interest of civil engineering students are: Strategy, Sports and Simulation. On the other hand, it is also observed that the less played genres are: Art Games, Action – Adventure and music games. Furthermore, results of the analysis are compared with the students weighted points. Outcomes are striking that there is a stable correlation between the students playing strategy games and their success points. Keywords: Video games, video game genres, students, civil engineering students, past video experiences. 1. Introduction Video Games (Vg) have progressively been preferred background, a randomly distributed questionnaire as indispensable and stable part of human life in method is applied to 200 civil engineering students. -

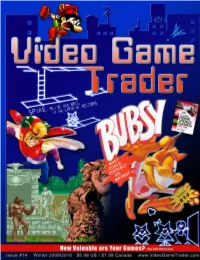

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Computer Entertainer / Video Game Update

ComputerEntertainer INCLUDES TiHii Wiidi© Cams Update > 5916 Lemona Avenue, Van Nuys, CA 91411 ©July, 1989 Volume 8, Number 4 $3.50 v ...CJE.S. News Continues! In This Issue... We Visit Accolade Epyx Goes to the Movies C.E.S. Wrap-Up Continues Stepping into the Epyx booth at CES gave sho wgoers a bit of the feeling of attending a Hollywood REVIEWS Include... movie premiere. The company showcased its lineup of new games with an entertaining video done Qix in the style of a movieland newsreel. Apropos of the newsreel presentation, Epyx showed SNOW ..../or Commodore 64 STRIKE, a flight simulation game with a theme as current as today's headlines. This action and DeathBringer strategy game for MS-DOS (MSR $44.95) and Commodore 64/128 ($34.95) puts players in the i Total Eclipse Fast Break cockpit of a fighter jet for a series of ten missions to destroy the heavily defended fields, refineries ...for Amiga and seagoing transport of South American drug lords. The missions take place over land and sea, MegaMan 2 as players must master aircraft carrier and airstrip takeoffs and landings, operate machine guns and Friday the 13th A/ heat-seeking missiles, and learn to maneuver over mountainous terrain in uncertain ...for Nintendo AT ATS Time Solders weather conditions while defending against local navy and air forces that support the drug kingpins. Alex Kidd: High-Tech World Epyx also showed underwater action that was realistic, current and believable in PROJECT ...for Sega NEPTUNE, a game that appeared to be a re-worked and refined version of the game previewed at the January CES under the title of "Undersea Commando." PROJECT NEPTUNE, which is TOP 15 COMPUTER GAMES involves 1. -

Yorba Times: Global Issues Noah Asher Golden Chapman University, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Yorba-Chapman Writing Partnership Anthology of College of Educational Studies Journalistic Writing Spring 2017 Yorba Times: Global Issues Noah Asher Golden Chapman University, [email protected] Alexa Tellez Yorba Academy for the Arts Allison Carlson Chapman University Brook-lynn Payne Yorba Academy for the Arts Dayana Camarena Yorba Academy for the Arts See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/yorba-chapman Recommended Citation Golden, N.A, et al. (2017). Yorba Times: Global issues. Yorba-Chapman Writing Partnership Anthology of Journalistic Writing. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/yorba-chapman/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Educational Studies at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yorba-Chapman Writing Partnership Anthology of Journalistic Writing by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Noah Asher Golden, Alexa Tellez, Allison Carlson, Brook-lynn Payne, Dayana Camarena, Jared Segundo, Jenna Dietrich, Amanda Moore, Lara Jacobson, Makenzie Edwards, Sakina Jaffery, Andrew Guzman, Anya Vandandaigue, Charlie Grant, Sunshine Durham, Ali Shehab, Dayna Sipila, Ashley Diaz, Tara Schrock, Claudia Doucette, Florencia Park, Samantha Cortes, Elora Estes, Sandra Noria, David Alvarez, Diana Lopez, Edwin Reyes, Haeley Arcos, Madi Spiegel, -

Exercise 2 (Flow Control) – Text-Based Artillery Game / Spring 2012

ITGM 315 / Fowler/ Exercise 2 (Flow Control) – Text-Based Artillery Game / Spring 2012 Exercise 2 - Text-Based Artillery Game DATE DUE: start of class 7 Hand in through the Dropbox Make sure your files are working with Visual Studio 2010! The turn-based artillery genre, popularized by the Worms series of games (which were based on the PC game Scorched Earth before them), involve players trying to shoot each other in a two- dimensional side-scrolling world with physics. On a player’s turn, he or she chooses a direction to shoot at and the initial speed of the shot. The player’s goal is to hit one of the other players. The earliest games of this genre were actually played on mainframes with text displays. We will create a simple version similar to these early games. An online version of the game written in java can be played at the Scorched Earth 2000 website. Single Shot, No Opponent First we’ll ask the player for an initial angle (of type int) and speed (of type float), and then calculate how far away the shot lands. We will need to make sure the player enters legal values for the numbers (this is called validation), and keep asking the player again until he or she gets it right. Specifically, the angle must be one of the following values: 15, 30, 45, 60 or 75 (smaller angles shoot straight ahead, while larger angles shoot straight up) and speed must be between 1 and 10. HINT: You may use a do-while loop to ask for the input, and validate it in the while condition. -

Modul Mengatasi Kecanduan Permainan Daring Elektronik (Pde Disorder)

MODUL MENGATASI KECANDUAN PERMAINAN DARING ELEKTRONIK (PDE DISORDER) LAYANAN BIMBINGAN SOSIAL BAGI SISWA KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji syukur penyusun panjatkan kehadirat Allah SWT atas segala rahmat dan hidayahNya, sehingga penyusun dapat menyelesaikan modul tentang Mengatasi Kecanduan Permainan Daring Elelktronik (Online Game Disorder) dengan baik. Harapan penyusun semoga degan adanya modul ini, membantu bagi para siswa khususnya mengenal dan memahami berbagai macam jenis permainan eleltronik dengan dampak- dampak yang ditimbulkannya. Akhir kata denngan segala kerendahan hati penyusun ucappkan kepada semua pihak atas egala bantuan dan dukungan yang telah diberikan dalam penyusunan modul ini. Penyusun menyadari masih jauuh dari sempurna, meskipun demikian semoga dapat bermanfaat bagi semua pihak. DAFTAR ISI KATA PENGANTAR ................................................................................. DAFTAR ISI................................................................................................. PENDAHULUAN......................................................................................... BAB IMENGENAL BEBAGAI MACAM GAME...................................... BAB II DAMPAK POSITIF GAME........................................................... a. Gme Membuat Orang Pintar b. Game Meningkatan Konsentrasi c. Ketajaman mata yang lebih cepat. d. Meningkatkan kinerja otak dan memacu otak dalam menerima cerita. e. Meningkatkan kemampuan membaca. f. BAB III DAMPAK NEGATIF GAME....................................................... -

PDF Bekijken

OSS voor Windows: Spellen Ook Ook Naam Functie Website Linux NL Make words from Anagramarama ja nee code.google.com/p/anagramarama given letters Armagetron Multiplayer arcade ja nee armagetronad.org Advanced style game Turn-based The Battle for strategiespel met een ja deel www.wesnoth.org Wesnoth fantasy thema Uncover pairs of identically colored Enigma ja nee www.nongnu.org/enigma Oxyd stones while solving puzzles Geperfectioneerde, Flightgear professionele ja ja www.flightgear.org vluchtsimulatie Strategiespel waarin Freeciv rijken worden ja ja freeciv.wikia.com opgebouwd Turn-based strategy FreeCol ja ja www.freecol.org based on Colonization Third person scrolling Kobo Deluxe ja nee www.olofson.net/kobodl 2D shooter Breakout-style arcade LBreakOut2 ja nee lgames.sourceforge.net/....LBreakout2 game Miniature golf and an Neverball ja nee neverball.org obstacle course An open-world space Oolite ja nee www.oolite.org opera Multiplayer action game in which you OpenClonk control clonks, small ja nee www.openclonk.org but witty and nimble humanoid beings "Evolution" of Panzer General II, a classic Open General nee nee opengeneral.sourceforge.net turn-based strategy game Real Time Strategy project recreating the OpenRA classic ja nee www.openra.net Command & Conquer titles Action game involving Pang Zero popping balloons with ja nee apocalypse.rulez.org/pangzero a harpoon Texas Hold 'em poker PokerTH ja ja www.pokerth.net simulator Portable Collection of thirty Puzzle four small one-player nee nee www.chiark.greenend.org.uk/~sgtatham/puzzles Collection puzzle games Scorched3D Artillery game ja nee www.scorched3d.co.uk Put all of the crates Sokoban YASC into the designated nee nee sourceforge.net/..../sokobanyasc areas by nudging them Educational math TuxMath ja nee tux4kids.alioth.debian.org/tuxmath arcade game Tux the Linux Penguin races down steep, Tux Racer ja nee tuxracer.sourceforge.net snow-covered mountains Typing tutor designed TuxTyping ja nee tux4kids.alioth.debian.org/tuxtype for children Bijgewerkt: 16 mei 2015. -

Independent Games What They Are and Are They Different

Jaakko Kemppainen Independent games What they are and are they different Master's thesis Digital Culture 20.2.2008 Jyväskylä University Department of Art and Culture Studies Jyväskylä JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Faculty of Humanities Department of Art and Culture Studies Tekijä – Author Jaakko Kemppainen Työn nimi – Title Independent games What they are and are they different Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Digital Culture Master's thesis Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages February 2008 98 p. + Appendices 18 p. Tiivistelmä – Abstract This research figures out, how the concept of independent games and independent game production is understood in the field of game industry. Some comparisons are made to music and movie industry, using literature and different internet sources to find out commonly used definitions for independent concept on different areas of entertainment business. Three level definition for independent productions is formed, mainly from the commerce point of view - independent, semi-independent and non-independent games and producers. Second part of this research is a quantitative genre comparison between non-independent games and independent games. For the use of the genre research, a study of game genres is made and basen on that, a game genre systemi is produced. Main finding of the quantitative research is, that independent game genre distribution is different in the case of non-independent games, but there are a lot of similarities within both non-independent and -

Emotion and Social Context in a Digital Game Experience

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Emotion and social context in a digital game experience J Matias Kivikangas Institute of Behavioural Sciences University of Helsinki, Finland Center for Knowledge and Innovation Research and Department of Information and Service Economy Aalto University, Finland Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Behavioural Sciences at the University of Helsinki in Auditorium 1, Siltavuorenpenger 1A, on the 17th of December, 2015, at 11 o’clock University of Helsinki Institute of Behavioural Sciences Studies in Psychology 115: 2015 Supervisors Professor Niklas Ravaja Department of Social Research, University of Helsinki, Finland, and Department of Information and Service Economy, Aalto University, Helsinki, Finland Docent Laura Pulkki-Råback Institute of Behavioural Sciences and Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, University of Helsinki, Finland Reviewers Associate Professor Regan Mandryk Department of Computer Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada Associate Professor James D. Ivory Department of Communication, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA Opponent Professor Wijnand IJsselsteijn Department of Industrial Engineering & Innovation Sciences, Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands ISSN-L 1798-842X ISSN 1798-842X ISBN 978-951-51-1817-2 (pbk.) ISBN 978-951-51-1818-9 (PDF) http://www.ethesis.helsinki.fi -

Pocket Tanks Mod Apk Android 1

Pocket tanks mod apk android 1 Continue Download Guests can't ask for updates! Pocket tanks Deluxe - No.1, No.1. Hearts. Players will control tanks located on mountain levels. With the help of a variety of on-board weapons, the user will destroy the enemy's equipment. To hit the target, you need to accurately calculate the trajectory of the projectile and the power of the shot. Exactly hit can be trained in a special mode, after which gamers are waiting for exciting battles and a lot of positive emotions. BlitWise Productions, Android 2.3 - Version: 2.3.0 $0 Pocket Tanks (MOD, Free Shopping) - This is a masterpiece of the gaming industry, which tells us about the constant battles between battle tanks, which are very difficult and impassable roads. Each side has a huge arsenal of weapons, with which you can not only destroy their opponents, but also cut the zone. Andro-Mod Games Mod Pocket Tanks (MOD, Unlocked) Pocket Tanks is an unusual tank battle simulator with several competitive modes, complex combat systems and mechanics, partly borrowed from the Worms series. Developers from BlitWise Productions, LLC offer in a duel mode 1-on-1 to deal with enemy equipment using available tools: machine guns, grenades, bombs and even mechanized robots. The goal is to cope with the task as quickly as possible, and even with minimal losses. And, if problems arise with this, then hacking for money will definitely make life easier! Pocket Tanks Size: 25.88 MB Version: 2.3.1 File Type: APK System: Android 2.3 or above Description: Pocket Tanks is a fast-paced artillery game that is easy to master, and fun to master. -

How Do You Say Watermelon?

Transmotion Vol 3, No 1 (2017) How do you say watermelon? JEANETTE BUSHNELL, JONATHAN TOMHAVE, TYLOR PRATHER We borrowed words from Thurman Hester’s sharing of Choctaw language and pedagogy for our title, “How do you say watermelon?” The elder’s question exemplified Choctaws’ respectful teaching while encouraging the student to find and understand relationships. Similarly, this paper presents the position and process of postindian gamer by centralizing experience, ours and the readers’ as conveyed via story. Our story of postindian gamers grounds itself in our experiences playing and learning about Sla’hal and other games played on Turtle Island prior to the colonizing invasion that began in 1492. We come as colonizer educated, indian educated, and indian educated postindians, using Vizenor’s vernacular. We come with indigenous lived experiences and recipients of teachings by indigenous elders of our ancestral nations as well as elders who are local to our current living place of Lushootseed speaking peoples of the Salish Sea. We name ourselves Postindian Gamers and Turtle Islanders—aləshək s’chəgwutsidabsh in local Lushootseed language. We call upon our experiences and the experiences of those who came before us. Our actions include creating and visioning a future of survivance gaming and games of survivance. We strive to bring historic philosophies of Turtle Islanders to contemporary gaming with an enactment of such philosophies in game goals, mechanics, aesthetics, language, value. This paper has four separately styled sections to create varied opportunities for readers to experience how very old indigenous games, particularly Sla’hal, inform contemporary game development (Adams et al.; Tomhave; Bushnell). -

An Empirical Study on Vocational School Students: Games Experience and Success Relation

Journal of Engineering Research and Applied Science Available at www.journaleras.com Volume 5(2), December 2016, pp 423-428 ISSN 2147-3471 © 2016 An empirical study on vocational school students: games experience and success relation Y.Arslan1,a, M.E. Akpinar2, M.S. Yildirim2, M.Evrensel3, E.Dogan2 1 Duzce University, Duzce Vocational School, Duzce, Turkey. 2 Manisa Celal Bayar University, Faculty of Engineering, Manisa, Turkey. 3 Manisa Celal Bayar University, Demirci Vocational School, Manisa, Turkey. Accepted 05 October 2016 Abstract Within the scope of this study, games playing experiences of vocational school students is examined to specify the most favored video game classifications that were played as a technician candidate and its contribution to their education. A questionnaire methodology is chosen and questions are randomly distributed to the vocational school students. This technique is applied to 221 technician candidates to work out their past video game preferences before becoming a member of technician department. The analysis of the questionnaire results indicates that the top three games classes in the interest of vocational school students are: Strategy, Sports and Simulation. But then, it is also ascertained that the less played types are: Art Games, Action – Adventure and music games. Moreover, results of the analysis are compared with the students weighted points. Outcomes are striking that there is a stable correlation between the students playing strategy games and their success points.. Keywords: Video game types; vocational school students; past video experiences 1. Introduction Computer Games (Cg) have increasingly been screen. favored as crucial and static part of human life in today’s world.