Simulacra in Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk Marcus Janni Pivato Many people seem to think that William Gibson invented The cyberpunk genre in 1984, but in fact the cyberpunk aesthetic was alive well before Neuromancer (1984). For example, in my opinion, Ridley Scott's 1982 movie, Blade Runner, captures the quintessence of the cyberpunk aesthetic: a juxtaposition of high technology with social decay as a troubling allegory of the relationship between humanity and machines ---in particular, artificially intelligent machines. I believe the aesthetic of the movie originates from Scott's own vision, because I didn't really find it in the Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968), upon which the movie is (very loosely) based. Neuromancer made a big splash not because it was the "first" cyberpunk novel, but rather, because it perfectly captured the Zeitgeist of anxiety and wonder that prevailed at the dawning of the present era of globalized economics, digital telecommunications, and exponential technological progress --things which we now take for granted but which, in the early 1980s were still new and frightening. For example, Gibson's novels exhibit a fascination with the "Japanification" of Western culture --then a major concern, but now a forgotten and laughable anxiety. This is also visible in the futuristic Los Angeles of Scott’s Blade Runner. Another early cyberpunk author is K.W. Jeter, whose imaginative and disturbing novels Dr. Adder (1984) and The Glass Hammer (1985) exemplify the dark underside of the genre. Some people also identify Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling as progenitors of cyberpunk. -

Alternate History – Alternate Memory: Counterfactual Literature in the Context of German Normalization

ALTERNATE HISTORY – ALTERNATE MEMORY: COUNTERFACTUAL LITERATURE IN THE CONTEXT OF GERMAN NORMALIZATION by GUIDO SCHENKEL M.A., Freie Universität Berlin, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (German Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2012 © Guido Schenkel, 2012 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines a variety of Alternate Histories of the Third Reich from the perspective of memory theory. The term ‘Alternate History’ describes a genre of literature that presents fictional accounts of historical developments which deviate from the known course of hi story. These allohistorical narratives are inherently presentist, meaning that their central question of “What If?” can harness the repertoire of collective memory in order to act as both a reflection of and a commentary on contemporary social and political conditions. Moreover, Alternate Histories can act as a form of counter-memory insofar as the counterfactual mode can be used to highlight marginalized historical events. This study investigates a specific manifestation of this process. Contrasted with American and British examples, the primary focus is the analysis of the discursive functions of German-language counterfactual literature in the context of German normalization. The category of normalization connects a variety of commemorative trends in postwar Germany aimed at overcoming the legacy of National Socialism and re-formulating a positive German national identity. The central hypothesis is that Alternate Histories can perform a unique task in this particular discursive setting. In the context of German normalization, counterfactual stories of the history of the Third Reich are capable of functioning as alternate memories, meaning that they effectively replace the memory of real events with fantasies that are better suited to serve as exculpatory narratives for the German collective. -

The Fundamental Articles of I.AM Cyborg Law

Beijing Law Review, 2020, 11, 911-946 https://www.scirp.org/journal/blr ISSN Online: 2159-4635 ISSN Print: 2159-4627 The Fundamental Articles of I.AM Cyborg Law Stephen Castell CASTELL Consulting, Witham, UK How to cite this paper: Castell, S. (2020). Abstract The Fundamental Articles of I.AM Cyborg Law. Beijing Law Review, 11, 911-946. Author Isaac Asimov first fictionally proposed the “Three Laws of Robotics” https://doi.org/10.4236/blr.2020.114055 in 1942. The word “cyborg” appeared in 1960, describing imagined beings with both artificial and biological parts. My own 1973 neologisms, “neural Received: November 2, 2020 plug compatibility”, and “softwiring” predicted the computer software-driven Accepted: December 15, 2020 Published: December 18, 2020 future evolution of man-machine neural interconnection and synthesis. To- day, Human-AI Brain Interface cyborg experiments and “brain-hacking” de- Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and vices are being trialed. The growth also of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven Scientific Research Publishing Inc. Data Analytics software and increasing instances of “Government by Algo- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International rithm” have revealed these advances as being largely unregulated, with insuf- License (CC BY 4.0). ficient legal frameworks. In a recent article, I noted that, with automation of http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ legal processes and judicial decision-making being increasingly discussed, Open Access RoboJudge has all but already arrived; and I discerned also the cautionary Castell’s Second Dictum: “You cannot construct an algorithm that will relia- bly decide whether or not any algorithm is ethical”. -

New Alt.Cyberpunk FAQ

New alt.cyberpunk FAQ Frank April 1998 This is version 4 of the alt.cyberpunk FAQ. Although previous FAQs have not been allocated version numbers, due the number of people now involved, I've taken the liberty to do so. Previous maintainers / editors and version numbers are given below : - Version 3: Erich Schneider - Version 2: Tim Oerting - Version 1: Andy Hawks I would also like to recognise and express my thanks to Jer and Stack for all their help and assistance in compiling this version of the FAQ. The vast number of the "answers" here should be prefixed with an "in my opinion". It would be ridiculous for me to claim to be an ultimate Cyberpunk authority. Contents 1. What is Cyberpunk, the Literary Movement ? 2. What is Cyberpunk, the Subculture ? 3. What is Cyberspace ? 4. Cyberpunk Literature 5. Magazines About Cyberpunk and Related Topics 6. Cyberpunk in Visual Media (Movies and TV) 7. Blade Runner 8. Cyberpunk Music / Dress / Aftershave 9. What is "PGP" ? 10. Agrippa : What and Where, is it ? 1. What is Cyberpunk, the Literary Movement ? Gardner Dozois, one of the editors of Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine during the early '80s, is generally acknowledged as the first person to popularize the term "Cyberpunk", when describing a body of literature. Dozois doesn't claim to have coined the term; he says he picked it up "on the street somewhere". It is probably no coincidence that Bruce Bethke wrote a short story titled "Cyberpunk" in 1980 and submitted it Asimov's mag, when Dozois may have been doing first readings, and got it published in Amazing in 1983, when Dozois was editor of1983 Year's Best SF and would be expected to be reading the major SF magazines. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

The New Order of Hitler: Virtual History, Fiction and Myth

DEBATER A EUROPA Periódico do CIEDA e do CEIS20 , em parceria com GPE e a RCE. N.13 julho/dezembro 2015 – Semestral ISSN 1647-6336 Disponível em: http://www.europe-direct-aveiro.aeva.eu/debatereuropa/ The New Order of Hitler: Virtual History, Fiction and Myth Sérgio Neto Researcher of CEIS20, University of Coimbra E-mail: [email protected] Abstract At the intersection of counterfactual Historiography and literary fantasy, the triumph of the Axis powers in World War II has been one of the main issues. The resurgence of a hypothetical IV Reich also results extensive. Similarly, cinema has not failed to go over the old question of “if”. This article intent to analyse some virtual literature and historical works of reference about the New European Order in order to discuss possible inspiration that science awoke this genre and concepts revolving around the revisionism and determinism. Keywords: New European Order; Counterfactuals; Dystopia; Historiography; Fantasy When the German army completed the conquest of Poland in September 1939 the New European Order began to take shape. The euphemistic name of that brutal military occupation was in fact more incisive than the name given to the Japanese occupied areas: Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere 1. But, the main issue was if Hitler’s projects achieved in a few years the degree of dehumanization promised by the propaganda with the so called Reich of a Thousand Years. Based on the assumptions outlined by Mein Kampf , as well as the improvisations made during the course of the war, the dreams and fantasies of world domination were analysed not only by the historiography, but widely widespread by the alternate story genre. -

Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick

EUGÊNIA BARTHELMESS Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentra- ção Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federai do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre. Orientadora: Prof.3 Dr.a BRUNILDA REICHMAN LEMOS CURITIBA 19 8 7 OF PHILIP K. DICK ERRATA FOR READ p -;2011 '6:€h|j'column iinesllll^^is'iiearly jfifties (e'jarly i fx|fties') fifties); Jl ' 1 p,.2Ò 6th' column line 16 space race space race (late fifties) p . 33 line 13 1889 1899 i -,;r „ i i ii 31 p .38 line 4 reel."31 reel • p.41 line 21 ninteenth nineteenth p .6 4 line 6 acien ce science p .6 9 line 6 tear tears p. 70 line 21 ' miliion million p .72 line 5 innocence experience p.93 line 24 ROBINSON Robinson p. 9 3 line 26 Robinson ROBINSON! :; 1 i ;.!'M l1 ! ! t i " i î : '1 I fi ' ! • 1 p .9 3 line 27 as deliberate as a deliberate jf ! •! : ji ' i' ! p .96 lin;e , 5! . 1 from form ! ! 1' ' p. 96 line 8 male dis tory maledictory I p .115 line 27 cookedly crookedly / f1 • ' ' p.151 line 32 why this is ' why is this I 1; - . p.151 line 33 Because it'll Because (....) it'll p.189 line 15 mourmtain mountain 1 | p .225 line 13 crete create p.232 line 27 Massachusetts, 1960. Massachusetts, M. I. T. -

{PDF EPUB} Batman Turning Points by Greg Rucka Search Abebooks

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Batman Turning Points by Greg Rucka Search AbeBooks. We're sorry; the page you requested could not be found. AbeBooks offers millions of new, used, rare and out-of-print books, as well as cheap textbooks from thousands of booksellers around the world. Shopping on AbeBooks is easy, safe and 100% secure - search for your book, purchase a copy via our secure checkout and the bookseller ships it straight to you. Search thousands of booksellers selling millions of new & used books. New & Used Books. New and used copies of new releases, best sellers and award winners. Save money with our huge selection. Rare & Out of Print Books. From scarce first editions to sought-after signatures, find an array of rare, valuable and highly collectible books. Textbooks. Catch a break with big discounts and fantastic deals on new and used textbooks. ISBN 13: 9781401213602. Explores the history of Batman's relationship with Commissioner James Gordon, as they fight crime in the streets of Gotham City. "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title. Shipping: FREE From United Kingdom to U.S.A. Other Popular Editions of the Same Title. Featured Edition. ISBN 10: 184576563X ISBN 13: 9781845765637 Publisher: Titan Books Ltd, 2007 Softcover. Customers who bought this item also bought. Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace. 1. Batman Turning Points TP (Paperback) Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English. Brand new Book. Written by Greg Rucka, Chuck Dixon and Ed Brubaker Art by Steve Lieber, Dick Giordano, Paul Pope and others Cover by Tim Sale Collecting the miniseries BATMAN TURNING POINTS #1-5! This story explores the relationship between Batman and Commisioner Gordon, and how it has developed through the years, from Batman's early days through sidekicks and even a broken back. -

Simulacra of Social Desire: Reflection on Collecting and the “Lost Toy Archive”

SIMON ORPANA siMulacrA oF soCiAl desire: reFleCtion on ColleCtinG And the “lost toy ArChive” In 2009, I started to construct an archive that records traces of the toys I collected and played with as a child. While most of these toys have been lost in various garage sales, moves and purges, I started to search out photographic records of my collections, and used these to evoke reflection regarding the role that toys have played in shaping my memories, identity and modes of relating to the world. Rather than simply amassing images, I started to make drawings of them in a sketchbook. This process was aided by my mother’s unearthing of a family photo album, spanning from the late seventies to the early eighties, which contained the originals of many of the images included in my archive. The act of re-drawing these images into my sketchbook expanded the microsecond of time captured in the photograph into a longer meditation through which details in the photos summoned memories and affect. This exercise challenged the abstract, spectacularized place the toys held in my adult imagination and placed the artifacts back into a context of 211 family, friends and personal history, offering a remedy to the “archive fever” SIMULACRA OF SOCIAL DESIRE that overtook me in early adulthood, when recollecting the physical toys I owned as a child became an obsessive preoccupation. The process by which the mass-produced toys of my youth were translated from mere simulacra into a meaningful personal narrative by employing the same logic of simulation is the general theme this paper explores. -

Deleuze and the Simulacrum Between the Phantasm and Fantasy (A Genealogical Reading)

Tijdschrift voor Filosofie, 81/2019, p. 131-149 DELEUZE AND THE SIMULACRUM BETWEEN THE PHANTASM AND FANTASY (A GENEALOGICAL READING) by Daniel Villegas Vélez (Leuven) What is the difference between the phantasm and the simulacrum in Deleuze’s famous reversal of Platonism? At the end of “Plato and the Simulacrum,” Deleuze argues that philosophy must extract from moder- nity “something that Nietzsche designated as the untimely.”1 The his- toricity of the untimely, Deleuze specifies, obtains differently with respect to the past, present, and future: the untimely is attained with respect to the past by the reversal of Platonism and with respect to the present, “by the simulacrum conceived as the edge of critical moder- nity.” In relation to the future, however, it is attained “by the phantasm of the eternal return as belief in the future.” At stake, is a certain dis- tinction between the simulacrum, whose power, as Deleuze tells us in this crucial paragraph, defines modernity, and the phantasm, which is Daniel Villegas Vélez (1984) holds a PhD from the Univ. of Pennsylvania and is postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Philosophy, KU Leuven, where he forms part of the erc Research Pro- ject Homo Mimeticus (hom). Recent publications include “The Matter of Timbre: Listening, Genea- logy, Sound,” in The Oxford Handbook of Timbre, ed. Emily Dolan and Alexander Rehding (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2018), doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190637224.013.20 and “Allegory, Noise, and History: TheArcades Project Looks Back at the Trauerspielbuch,” New Writing Special Issue: Convo- luting the Dialectical Image (2019), doi: 10.1080/14790726.2019.1567795. -

1539817842296.Pdf

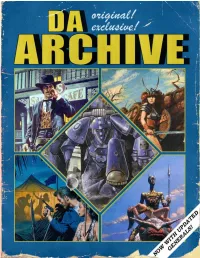

OCTOBER 17th 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Exhibition Hall

exhibition hall 15 the weird west exhibition hall - november 2010 chris garcia - editor, ariane wolfe - fashion editor james bacon - london bureau chief, ric flair - whooooooooooo! contact can be made at [email protected] Well, October was one of the stronger months for Steampunk in the public eye. No conventions in October, which is rare these days, but there was the Steampunk Fortnight on Tor.com. They had some seriously good stuff, including writing from Diana Vick, who also appears in these pages, and myself! There was a great piece from Nisi Shawl that mentioned the amazing panel that she, Liz Gorinsky, Michael Swanwick and Ann VanderMeer were on at World Fantasy last year. Jaymee Goh had a piece on Commodification and Post-Modernism that was well-written, though slightly troubling to me. Stephen Hunt’s Steampunk Timeline was good stuff, and the omnipresent GD Falksen (who has never written for us!) had a couple of good piece. Me? I wrote an article about how Tomorrowland was the signpost for the rise of Steampunk. You can read it at http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/10/goodbye-tomorrow- hello-yesterday. The second piece is all about an amusement park called Gaslight in New Orleans. I’ll let you decide about that one - http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/10/gaslight- amusement. The final one all about The Cleveland Steamers. This much attention is a good thing for Steampunk, especially from a site like Tor.com, a gateway for a lot of SF readers who aren’t necessarily a part of fandom.