Information, Archives and Financial History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bank Restriction Act and the Regime Shift to Paper Money, 1797-1821

European Historical Economics Society EHES WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY | NO. 100 Danger to the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street? The Bank Restriction Act and the regime shift to paper money, 1797-1821 Patrick K. O’Brien Department of Economic History, London School of Economics Nuno Palma Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute Department of Economics, Econometrics, and Finance, University of Groningen JULY 2016 EHES Working Paper | No. 100 | July 2016 Danger to the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street? The Bank Restriction Act and the regime shift to paper money, 1797-1821* Patrick K. O’Brien Department of Economic History, London School of Economics Nuno Palma Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute Department of Economics, Econometrics, and Finance, University of Groningen Abstract The Bank Restriction Act of 1797 suspended the convertibility of the Bank of England's notes into gold. The current historical consensus is that the suspension was a result of the state's need to finance the war, France’s remonetization, a loss of confidence in the English country banks, and a run on the Bank of England’s reserves following a landing of French troops in Wales. We argue that while these factors help us understand the timing of the Restriction period, they cannot explain its success. We deploy new long-term data which leads us to a complementary explanation: the policy succeeded thanks to the reputation of the Bank of England, achieved through a century of prudential collaboration between the Bank and the Treasury. JEL classification: N13, N23, N43 Keywords: Bank of England, financial revolution, fiat money, money supply, monetary policy commitment, reputation, and time-consistency, regime shift, financial sector growth * We are grateful to Mark Dincecco, Rui Esteves, Alex Green, Marjolein 't Hart, Phillip Hoffman, Alejandra Irigoin, Richard Kleer, Kevin O’Rourke, Jaime Reis, Rebecca Simson, Albrecht Ritschl, Joan R. -

861 Sq Ft Headquarters Office Building Your Own Front Door

861 SQ FT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDING YOUR OWN FRONT DOOR This quite unique property forms part of the building known as Rotherwick House. The Curve comprises a self-contained building, part of which is Grade II Listed, which has been comprehensively refurbished to provide bright contemporary Grade A office space. The property — located immediately to the east of St Katharine’s Dock and adjoining Thomas More Square — benefits from the immediate area which boasts a wide variety of retail and restaurant facilities. SPECIFICATION • Self-contained building • Generous floor to ceiling heights • New fashionable refurbishment • Full-height windows • New air conditioning • Two entrances • Floor boxes • Grade II Listed building • LG7 lighting with indirect LED up-lighting • Fire and security system G R E A ET T THE TEA TRE E D S A BUILDING OL S T E R SHOREDITCH N S HOUSE OLD STREET T R E E T BOX PARK AD L RO NWEL SHOREDITCH CLERKE C I HIGH STREET T Y R G O O A S D W S F H A O E R L U A L R T AD T H I O R T R N A S STEPNEY D’ O O M AL G B N A GREEN P O D E D T H G O T O WHITECHAPEL A N N R R R O D BARBICAN W O CHANCERY E A FARRINGDON T N O LANE D T T E N H A E M C T N O C LBOR A D O HO M A IGH MOORGATE G B O H S R R U TOTTENHAM M L R LIVERPOOL P IC PE T LO E COURT ROAD NDON WA O K A LL R N R H STREET H C L C E E O S A I SPITALFIELDS I IT A A W B N H D L E W STE S R PNEY WAY T O J R U SALESFORCE A E HOLBORN B T D REE TOWER E ST N I D L XFOR E G T O W R E K G ES H ALDGATE I A H E N TE A O M LONDON MET. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, Hth February 1964 1251 B. W. Blydenstein &

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, HTH FEBRUARY 1964 1251 B. W. BLYDENSTEIN & CO. Persons of whom the Company or Partnership consists Name Residence Occupation Rein Adriaan Vreede . "Byways", Hazelwood Lane, Chipstead, Surrey Banker Hendrik Hendrikus Oerlemans . " The Cottage ", Havant Road, Emsworth, Hants Banker The Twentsche Bank (London) 54/55/56 Threadneedle Street, London E.C.2 . Holding Company Limited Netherlands Trading Society 54/55/56 Threadneedle Street, London E.G.2. Holding Company (London) Ltd. Name of Place where the Business is carried on 54/55/56 Threadneedle Street, London E.C.2. THE CANADIAN IMPERIAL BANK OF COMMERCE Incorporated with limited liability in Canada Names of Places where the Business is carried on 2 Lombard Street, London E.C.3. 48 Berkeley Square, London W.I. THE CHASE MANHATTAN BANK Incorporated in the State of New York, United States of America Names of Places where the Business is carried on 6 Lombard Street, London E.C.3. 46 Berkeley Square, London W.I THE COMMERCIAL BANKING COMPANY OF SYDNEY LIMITED Incorporated in New South Wales with Limited Liability Names of Places where the Business is carried on 27/32 Old Jewry, London E.C.2. 49/50 Berkeley Street, London W.I. THE COMMERCIAL BANK OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED Incorporated in Victoria, Australia Names of Places where the Business is carried on 12 Old Jewry, London E.C.2. 34 Piccadilly, London W.I COMMONWEALTH SAVINGS BANK OF AUSTRALIA Constituted under the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia by Act of Parliament cited as the Commonwealth Banks Act, 1959 Names of Places where the Business is carried on 8 Old Jewry, London E.C.2 Bush House, Aldwych, London W.C.2. -

Liverpool Street Bus Station Closure

Liverpool Street bus station closed - changes to routes 11, 23, 133, N11 and N133 The construction of the new Crossrail ticket hall in Liverpool Street is progressing well. In order to build a link between the new ticket hall and the Underground station, it will be necessary to extend the Crossrail hoardings across Old Broad Street. This will require the temporary closure of the bus station from Sunday 22 November until Spring 2016. Routes 11, 23 and N11 Buses will start from London Wall (stop ○U) outside All Hallows Church. Please walk down Old Broad Street and turn right at the traffic lights. The last stop for buses towards Liverpool Street will be in Eldon Street (stop ○V). From there it is 50 metres to the steps that lead down into the main National Rail concourse where you can also find the entrance to the Underground station. Buses in this direction will also be diverted via Princes Street and Moorgate, and will not serve Threadneedle Street or Old Broad Street. Routes 133 and N133 The nearest stop will be in Wormwood Street (stop ○Q). Please walk down Old Broad Street and turn left along Wormwood Street after using the crossing to get to the opposite side of the road. The last stop towards Liverpool Street will also be in Wormwood Street (stop ○P). Changes to routes 11, 23, 133, N11 & N133 Routes 11, 23, 133, N11 & N133 towards Liverpool Street Routes 11 & N11 towards Bank, Aldwych, Victoria and Fulham Route 23 towards Bank, Aldwych, Oxford Circus and Westbourne Park T E Routes 133 & N133 towards London Bridge, Elephant & Castle, -

NEWSLETTER MAY 2017 Proof 08/05/2017 13:58 Page 1 NEWSLETTER

BA NEWSLETTER MAY 2017_proof 08/05/2017 13:58 Page 1 NEWSLETTER www.barbicanassociation.com May 2017 Trafficam writing this shortly after “magic”our AGM – thank promised to take and up with London Transporthealthy the adjoining residential streets you to the many of you who came. Our poor state of Barbican Tube station and said he areas on Saturdays. speaker Christopher Hayward, chairman of would get the City to look at improving the Westminster has CHAIR’S the City’s Planning and Transportation cleanliness and design of the pavement in recently included a CORNER ICommittee, spoke with some passion about his Aldersgate Street outside. He was also urged to similar provision. It’s and the City’s desire to see “healthy” streets for put pressure on London Underground over tube particularly timely because the City is currently pedestrians; the continuing need for tall noise under the estate, to do something about consulting on its Code of Practice for buildings in the City; the impact of Crossrail; and light pollution in office blocks, and stop Deconstruction and Construction in the City – the Cultural Hub. developers building ugly buildings. which is the policy that governs construction Streets need to be safe but also healthy he One of the City’s major proposals to improve sites on all aspects, from hours of work, said, and he wanted the City’s streets to give the streets is its scheme to restrict access at pollution, and deliveries to archaeology and more priority to pedestrians – that linked with Bank junction: from 22 May only buses and wildlife. -

52–56 Leadenhall Street • London EC3 INTRODUCING the HALLMARK BUILDING WELCOME an Iconic Grade a Office Space in a Prime EC3 Location

52–56 Leadenhall Street • London EC3 INTRODUCING THE HALLMARK BUILDING WELCOME An iconic Grade A office space in a prime EC3 location. Restored to the highest standard, bringing contemporary quality to a classic building, TO THE creating a beautiful working environment. Redesigned by renowned architects, Orms, this piece of history has been elegantly updated and offers 36,471 sq ft of available accommodation, DIFFERENCE with exceptional ceiling heights, bright open floors and characterful features. Sophistication with a truly unique style, contemporary with character, this is the definition of distinction. Welcome to the Difference Welcome to The Hallmark Building 2 | The Hallmark Building Welcome to The Difference | 3 COMMON AREAS UNCOMMON TOUCHES 01. With two separate entrances to the building, one on Leadenhall Street and one on Fenchurch Street, the interlinked receptions, stairways, lifts and WCs have been beautifully refurbished with inspired interior design touches that take this piece of history to the next level. 02. 4 | The Hallmark Building 03. 01. LEADENHALL STREET RECEPTION Fully refurbished, high specification reception area 02. LEADENHALL STREET TOUCH DOWN The newly designed reception incorporates bench style desking and soft seating to create a holding area for clients or an informal break out area for tenants 03. LEADENHALL STREET RECEPTION DESK A bright and contemporary welcome 04. 05. FENCHURCH STREET RECEPTION A newly configured reception 05. LEADENHALL STREET FAÇADE Historic exterior 04. The Building | 5 06. 6 | The Hallmark Building RESTORED & RENOVATED TO AN EXCEPTIONAL STANDARD 07. The refurbishment at The Hallmark Building O6. provides brand new Cat A office space PART SECOND FLOOR 9,197 sq ft of Grade A office space with the soul and substance of a landmark London building. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 28Th February 1977 2779

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 28TH FEBRUARY 1977 2779 BANK OF NEW ZEALAND Incorporated by Act of the General Assembly of New Zealand, 29th July 1861 Names of Places where the Business is carried on 1 Queen Victoria Street, London EC4P 4HE 54 Regent Street, London W1R 5PJ 30 Royal Opera Arcade, London SW1Y 4UY THE BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA Incorporated in Canada with Limited Liability Names of Places where the Business is carried on 10 Berkeley Square, London W1X 6DN 12 Berkeley Square, London W1X 6HU 62/63 Threadneedle Street, London EC2P 2LS THE BANK OF SCOTLAND Names of Places where the Business is carried on 30 Bishopsgate, London EC2P 2EH 140 Kensington High Street, London W8 7RN 16/18 Piccadilly, London W1V OAH 61 Hide Hill, Berwick upon Tweed, Northumberland 57/60 Haymarket, London SW1Y 4QY TD15 1EN 332 Oxford Street, London WIN ODJ 13 Market Place, Wooler, Northumberland NE71 6LJ BANQUE DE L'INDOCHINE ET DE SUEZ Incorporated in France with Limited Liability Name of Place where the Business is carried on 62/64 Bishopsgate, London EC2N 4AR BANQUE POUR LE COMMERCE CONTINENTAL Incorporated in Switzerland with Limited Liability Name of Place where the Business is carried on Lee House, London Wall, London EC2Y SAY BIBBY BROS. & COMPANY Persons of whom the Partnership consists Name Residence Occupation Derek James Bibby .... Willaston Grange, Hadlow Road, Willaston, Wirral, Banker and Shipowner Merseyside L64 2UN Gerald O'Brien Harding . Dunstan Wood, Burton, Wirral, Merseyside Banker and Shipowner L64 8TG David John Griggs . .140 Birkenhead -

The Aon Centre at the Leadenhall Building

The Aon Centre at The Leadenhall Building The Aon Centre The LeadenhallSouth Place Building +44 (0) 207 086 5516 122 LeadenhallMoorfields Street [email protected] London Eldon Street EC3VMoorgate 4ANMoorgate A501 Middlesex Street Bishopsgate New Street London Wall A1211 Liverpool Street Blomfield Street A10 Old Broad Street Wormwood Street Moorgate Middlesex Street A1211 A1211 A10 Cutler Street Old Broad Street Houndsditch St Helens Place Bishopsgate Gt St Helens Bury Court A1211 Throgmorton Street A1211 St Botolph Street A1210 Bury Street Undershaft Threadneedle Street St Mary Axe Dukes Place Aldgate Bartholomew Lane Bartholomew A1213 The Leadenhall Aldgate High Street Building Bank Threadneedle Street Finch Lane Leadenhall Street Leadenhall Street Cornhill St Botolph Street Lombard Street Aldgate Jewry Street Bank DLR Lime St Birchin Lane Biliter Street Gracechurch Street Whittington Ave Fenchurch Ave King William Street Lloyd’s Avenue Fenchurch Street Vine Street Minories Lombard Street Fenchurch Pl Lime St Fenchurch Street Fenchurch Street Fenchurch Street Crosswall Minores Cannon Street Cooper’s Row Goodman’s Yard Gracechurch Street Mincing Lane Mincing Crutched Friars Monument Mark Lane Tower Gateway Eastcheap DLR Transport links and walking times to The Aon Centre at The Leadenhall Building Liverpool Street National Rail Metropolitan Line Central Line Circle Line Hammersmith & City LIne • • • • 8 minutes Bank • Central Line • Waterloo & City Line • Northern Line DLR 6 minutes Aldgate • Circle Line • Metropolitan Line 6 minutes Fenchurch Street National Rail 5 minutes Monument • District Line • Circle Line 5 minutes Tower Gateway DLR 9 minutes Risk. Reinsurance. Human Resources.. -

Threadneedles You Will Find Us in the Heart of the City of London

Welcome to Threadneedles Our meeting spaces You will find us in the heart of the City of London – a former Three state-of-the-art meeting rooms, Capital, Sterling Victorian banking hall dating back to 1856, cleverly converted and Traders, are equipped to accommodate up to 35 into a five-star boutique hotel. Be it for a meeting, dining or delegates. Room facilities vary with LCD projector and a special celebration, our private rooms cater for all group sizes screen or plasma TV, conference phone, flipchart and pens, and are complemented with modern British cuisine, created pads and pencils, white board and lighting syst em control by head chef Stephen Smith. The highest levels of quality and making them suitable for a variety of events including sales service guarantee a successful event every time. presentations and roadshows. In the heart of the city Exclusive hire Threadneedles is located in ’The City of London’ the most Marco Pierre White Wheeler’s of St. James’s Oyster Bar & Grill historic part of the capital and home to some of its most Room is available for exclusive hire. Combining the two spaces iconic buildings such as the Bank of England, the Gherkin, for a stand-up reception offers a capacity for up to 200 guests the Shard, St Pauls Cathedral, Tate Modern and Tower Bridge. while up to 80 guests can be accommodated for a seated Many of the world’s leading finance, law and insurance firms dinner. For a sophisticated Champagne reception or lavish have offices located in this ‘Square Mile’ and Threadn eedles cocktail party, the dome lounge offers the perfect setting for is located a few minutes walk away from most. -

Capital Markets Day 2020

AlzChem Group AG March 26, 2020 Berenberg Office London th 5 Floor 60 Threadneedle Street London EC2R 8HP, UK 2020 CAPITAL MARKETS DAY WWW.ALZCHEM.COM AlzChem Group AG – Capital Markets Day – March 26, 2020 AGENDA TIME 09:30 a.m. Registration AlzChem Group AG at a glance 10:00 a.m. AlzChem combines history and innovation! 10:30 a.m. Financials & Outlook Our Blockbuster Creamino® 11:15 p.m. The start of own distribution 12:15 p.m. Break Working Lunch 12:30 p.m. Products and Markets – Fit for the future 01:30 p.m. Q&A 02:00 p.m. End SPEAKER Dr. Georg Weichselbaumer, CSO Andreas Niedermaier, CEO Klaus Englmaier, COO YOUR CONTACT @ ALZCHEM GROUP AG Investor Relations & Communications, T +49 8621 86-2888, [email protected] 2 AlzChem Group AG – Capital Markets Day – March 26, 2020 REGISTRATION & ACCOMMODATION REGISTRATION Please click here to register for the Capital Markets Day: Link, QR-Code: DATE ACCOMMODATION March 25 – 26 Clayton City of London (Link) 10 New Drum Street, Tower Hamlets, London, E1 7AT, UK GBP 244.00 incl. Tax - Deluxe Room Leonardo Royal Hotel London Tower Bridge (Link) 45 Prescot Street, Tower Hamlets, London, E1 8GP, UK GBP 218.40 incl. Tax - Superior Room Apex London Wall Hotel (Link) 7 - 9 Copthall Avenue, City of London, London, EC2R 7NJ, UK GBP 336.00 incl. Tax - Superior Room YOUR CONTACT @ ALZCHEM GROUP AG Investor Relations & Communications, T +49 8621 86-2888, [email protected] 3 AlzChem Group AG – Capital Markets Day – March 26, 2020 TRAVEL DETAILS INFORMATION Location Berenberg Office London 5th Floor 60 Threadneedle Street London EC2R 8HP, UK Nearest Tube Bank Tube Station Station Princes St, London EC3V 3LA, UK This station connects with the Central, Northern, District, Circle and Waterloo & City lines. -

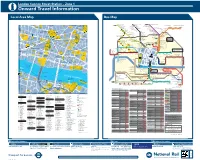

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Palmers Green North Circular Road Friern Barnet Halliwick Park 149 S GRESHAM STREET 17 EDMONTON R 141 1111 Guildhall 32 Edmonton Green 65 Moorgate 12 A Liverpool Street St. Ethelburga’s Centre Wood Green I 43 Colney Hatch Lane Art Gallery R Dutch WALTHAMSTOW F for Reconcilation HACKNEY 10 Church E Upper Edmonton Angel Corner 16 N C A R E Y L A N E St. Lawrence 17 D I and Peace Muswell Hill Broadway Wood Green 33 R Mayor’s 3 T 55 ST. HELEN’S PLACE for Silver Street 4 A T K ING S ’S ARMS YARD Y Tower 42 Shopping City ANGEL COURT 15 T Jewry next WOOD Hackney Downs U Walthamstow E E & City 3 A S 6 A Highgate Bruce Grove RE 29 Guildhall U Amhurst Road Lea Bridge Central T of London O 1 E GUTTER LANE S H Turnpike Lane N St. Margaret G N D A Court Archway T 30 G E Tottenham Town Hall Hackney Central 6 R O L E S H GREEN TOTTENHAM E A M COLEMAN STREET K O S T 95 Lothbury 35 Clapton Leyton 48 R E R E E T O 26 123 S 36 for Whittington Hospital W E LOTHBURY R 42 T T 3 T T GREAT Seven Sisters Lea Bridge Baker’s Arms S T R E E St. Helen S S P ST. HELEN’S Mare Street Well Street O N G O T O T Harringay Green Lanes F L R D S M 28 60 5 O E 10 Roundabout I T H S T K 33 G M Bishopsgate 30 R E E T L R O E South Tottenham for London Fields I 17 H R O 17 Upper Holloway 44 T T T M 25 St. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Port Health & Environmental

Public Document Pack Port Health & Environmental Services Committee Date: TUESDAY, 3 MARCH 2020 Time: 11.30 am Venue: COMMITTEE ROOM 3, 2ND FLOOR, WEST WING, GUILDHALL Members: Jeremy Simons (Chairman) Sophie Anne Fernandes Deputy Keith Bottomley (Deputy Alderman Sir Roger Gifford Chairman) Christopher Hill Deputy John Absalom Deputy Wendy Hyde Caroline Addy Deputy Jamie Ingham Clark Rehana Ameer Alderman Gregory Jones QC Alexander Barr Shravan Joshi Adrian Bastow Vivienne Littlechild Deputy John Bennett Andrien Meyers Peter Bennett Deputy Brian Mooney Tijs Broeke Deputy Joyce Nash John Chapman Deputy Richard Regan Peter Dunphy Henrika Priest Mary Durcan Jason Pritchard Deputy Kevin Everett Deputy Elizabeth Rogula John Edwards Mark Wheatley Anne Fairweather Enquiries: Rofikul Islam Tel. No: 020 7332 1174 [email protected] Lunch will be served at the rising of the Committee. N.B. Part of this meeting could be the subject of audio or video recording. John Barradell Town Clerk and Chief Executive AGENDA Part 1 - Public Agenda 1. APOLOGIES 2. MEMBERS' DECLARATIONS UNDER THE CODE OF CONDUCT IN RESPECT OF ITEMS ON THE AGENDA 3. MINUTES To agree the public minutes and summary of the meeting held on Tuesday, 14 January 2020. For Decision (Pages 1 - 8) 4. THAMES ESTUARY PARTNERSHIP ELECTION To appoint a Representative to the Thames Estuary Partnership. For Decision 5. OUTSTANDING ACTIONS Report of the Town Clerk. For Information (Pages 9 - 12) 6. UPDATE ON THE IMPACT OF THE UK LEAVING THE EU (BREXIT) ON PORT HEALTH & PUBLIC PROTECTION Report of the Director of Markets and Consumer Protection For Information (Pages 13 - 18) 7.