Canada's NATO Commitments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOR REFERENCE USE ONL Y DO NOT Removt from LIBRARY

Canada. F isbcries Service Maritimes Region. R csource Development Branch MANUSCRIPT REPORT I+ Environment Canada Environnement Canada RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT BRANCH .. " ' IÎÏI ~ Îl ~l Ïl\ij fü1imÎ l~I Îl \ i1 li~ ~Î~Ïil l I 'J 09093266 A Preliminary Investigation of the Striped Bass, Roccus saxatilis, Fishery Resource in the Annapolis River System, and the General Distribution of Striped Bass in Other Areas in Southwestern Nova Scotia by G. H. PENNEY FOR REFERENCE USE ONL Y DO NOT REMOvt FROM LIBRARY f h~trlts Stnlct 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 Hallfa1, N.S. 1l7d.- Restricted MANUSCRIPT REPORT No. 73- 4 A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION OF THE STRIPED BASS, Roccus saxatilis ~ FISHERY RESOURCE IN THE ANNAPOLIS RIVER SYSTEM, AND THE GENERAL DISTRIBUTION OF STRIPED BASS IN OTHER AREAS IN SOUTHWESTERN NOVA SCOTIA BY G.H. PENNEY Restricted A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION OF THE STRIPED BASS, Roccus s axatilis , FISHERY RESOURCE IN THE ANNAPOLIS RIVER SYSTEM, AND THE GENERAL DISTRIBUTION OF STRIPED BASS IN OTHER AREAS IN SOUTHWESTERN NOVA SCOTIA BY G.H. PENNEY DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT FISHERIES SERVICE RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT BRANCH HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA MARCH, 1973. CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION . • . • . • . • . • . • 1 METHODS 8 RESULTS 10 (a) Angling Statistics (1951-1972)-Annapolis River system . ....................................... 10 (b) Length, Weight, Sex, and Age of Striped Bass sampled from the Annapolis River in 1972 .....• 12 (c) Residence Distribution of Anglers from which Samples were obtained ........................ 16 (d) Angling Pressure for Striped Bass during June, July, and August, 1972, at the Annapolis 18 Causeway ..............•....................... (e) General Distribution and Abundance of Striped Bass in Other Areas in Southwestern Nova 20 Scotia ....................................... DISCUSSION - RECOMMENDATIONS ....................... -

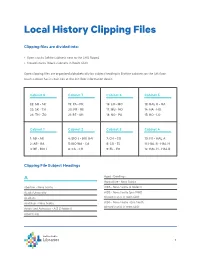

Local History Clipping Files

Local History Clipping Files Clipping files are divided into: • Open stacks (white cabinets next to the LHG Room) • Closed stacks (black cabinets in Room 440) Open clipping files are organized alphabetically by subject heading in 8 white cabinets on the 4th floor (each cabinet has its own key at the 4th floor information desk): Cabinet 8 Cabinet 7 Cabinet 6 Cabinet 5 22: SH - SK 19: PA - PR 16: LO - MO 13: HAL R - HA 23: SK - TH 20: PR - RE 17: MU - NO 14: HA - HO 24: TH - ZO 21: RE - SH 18: NO - PA 15: HO - LO Cabinet 1 Cabinet 2 Cabinet 3 Cabinet 4 1: AB - AR 4: BIO J - BIO U-V 7: CH - CO 10: FO - HAL A 2: AR - BA 5: BIO WA - CA 8: CO - EL 11: HAL B - HAL H 3: BE - BIO I 6: CA - CH 9: EL - FO 12: HAL H - HAL R Clipping File Subject Headings A Aged - Dwellings Agriculture - Nova Scotia Abortion - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia (2 folders) Acadia University AIDS - Nova Scotia (pre-1990) Acadians (closed stacks in room 440) Acid Rain - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia - Eric Smith (closed stacks in room 440) Actors and Actresses - A-Z (3 folders) Advertising 1 Airlines Atlantic Institute of Education Airlines - Eastern Provincial Airways (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Atlantic School of Theology Airplane Industry Atlantic Winter Fair (closed stacks in room 440) Airplanes Automobile Industry and Trade - Bricklin Canada Ltd. Airports (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Algae (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Canadian Motor Ambulances Industries (closed stacks in room 440) Amusement Parks (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Lada (closed stacks in room 440) Animals Automobile Industry and Trade - Nova Scotia Animals, Treatment of Automobile Industry and Trade - Volvo (Canada) Ltd. -

A Guide to Our Commemorative Banners

A Guide to Our Commemorative Banners Royal Canadian Legion General Alexander Ross Branch #77 Yorkton SK Canada Index of Veterans Acoose, Fred ............................................ 4 Miller, John ............................................ 24 Alexson, Victor J. ...................................... 4 Mogor, Sidney ........................................ 25 Arnold, George ......................................... 5 Morley, Allan C. ...................................... 25 Austman, Walter C. .................................. 5 Morrison, Ewen ...................................... 26 Bischop, Russell ........................................ 6 Morrison, Finlay A. ................................. 26 Bode, Rudolf ............................................. 6 Muir, W. Ron .......................................... 27 Bodnaryk, Fred ......................................... 7 O'Soup, Glen .......................................... 27 Borys, Steven ........................................... 7 Palmer, Mitchell G.J. .............................. 28 Bretherton, Nicholas ................................ 8 Palmer, Michael H.J. .............................. 28 Brown, Gordon L. ..................................... 8 Parr, W.J.W. (Jack) ................................. 29 Bryan, Ronald ........................................... 9 Pelly, Joseph Sr. ...................................... 29 Bucsis, Raymond ...................................... 9 Printz, George W. ................................... 30 Bunzenmeyer, Randy ............................ -

Dental Treatment Workload and Cost of Newly Enrolled Personnel in the Canadian Forces

Dental treatment workload and cost of newly enrolled personnel in the Canadian Forces [A study of the 2007 and 2008 recruit population] by Constantine Batsos A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master in Science in Dental Public Health Graduate Department of Dentistry University of Toronto © Copyright by Constantine Batsos (2010) Dental treatment workload and cost of newly enrolled personnel in the Canadian Forces [A study of the 2007 and 2008 recruit population] Constantine Batsos Master in Science in Dental Public Health Graduate Department of Dentistry University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Aim: To describe and analyze the demographic profile and the dental treatment needs, workload and costs of the 2007 and 2008 CF recruit population (N=10,641). Method: Treatment procedures and costs were aggregated and calculated, beginning from the date of a member’s enrolment, over a period that ranged between 13 to 36 months. Associations between treatment services and the demographic variables were tested using one-way ANOVA and chi-square tests. Independent samples T-test was used to compare means. Linear regression models were used to determine the influence of demographic variables on treatment cost. Results: Treatment needs and costs varied with recruit age, gender, rank, first language (French/English), birthplace (Canada/Foreign), tobacco use, province and census tract. The cost of treatment for the entire population was $13.9M. Mean cost per recruit was $1224 over an average period of 26 months. Outsource costs ($2.9M) were driven by referrals for restorative, endodontic and oral surgery procedures. ii Dedication To Peggy, for her unwavering patience, support and understanding, and for bringing happiness into my life. -

I{Ajor D. R. Czop

THB TMPACT OF I{ILTTARY B,\SE CLOSURES UPON THE LOCAL COI.,TUUNTTY Â thesis presented to the Faculty of Graduate studies ln partial_ fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of l,{aster of City planning by I{ajor D. R. Czop Department of City planning University of l,.lanitoba Iriarch, l9B0 THE ]MPACT OF MILiTARY BASE CLOSURES UPON THE LOCAL COMMUNITY BY MAJOR DAVID RONALD CZOP A thesis sLrbrnitted to the Faculty ol'GradLrate Studies of thc univcrsity.' ol ltiauitob¿r in partial 1ìrlf-illnlcnt of- thc rec¡Lrire rrrc¡ts of thc' degree of MASTER OF CITY PLANNING J o r980 Per¡nission has becn grarrte cl to thc LIIIIìAIì\' OF TIII UNIVEIì- SITY OF N.IANlTOBA ro lt'nd or se'll copics of this thesis, to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA ro nricrofilnr this thesis and to lcnd or sell copics c¡f'thc l'ilnl. ancl UNIVhRSITY N{ICIìOFILNIS to publish an abstract of'this thc.sis. TIte author reserves other ¡rublicatiort rights. allcl lleithc'r thc' tltcsis nol extellsivc extracts lj'oln it nla\/ bù llrintc'cl or othcr- rvisr rr'plorl rrecil n'il.lrorrt tllc urrllrrtr's rvrittcll ltcrrrrissiorr. For I'laureen TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRAOT oo o" o.....c. o o "o. ôc ô ô c c. c o co o........... o o v ACKNO\^ILEDGEMTf,{TS c. c.... o o.. o. c o... o.. o. ô. .. .. ..... c vi Lrsr 0F FTGURES AND TABLES .......oo..cec.....oo..co, ABREVTATTONS vii c'o c.... o..-..... c-... o... c........ c ô.. -

Schedule D Intermediate Weight Roads

Schedule D Intermediate Weight Roads Revised August 23, 2021 Annapolis County 1. Trunk 1, from Vault Road easterly to Kings County Line, 2.1 km. 2. Trunk 1, from Mount Hanley Road easterly to Department Garage 0.4 km west of Brooklyn Street, 4.1 km. 3. Trunk 1, from Highway 101 Exit 20 easterly to McKeown Bridge, 13.7 km. 4. Trunk 1, from CFB Cornwallis at Clementsport easterly to Annapolis Royal Town Line, 15.3 km. 5. Trunk 10, from Middleton Town Line southerly to Lunenburg County Line, 49.2 km. 6. Route 201, from Al Haley Road easterly to Morses Bridge, 11.9 km. 7. Route 201, from Trout Lake Mountain Road easterly to Trunk 10, 10.8 km. 8. Route 201, from Trunk 8 easterly to Round Hill Road, 9.0 km. 9. Route 221, from Trunk 1 near Wilmot northerly to Kings County Line, 4.9 km. 10. Route 362, from Brooklyn Street northerly to Lewis Road, 2.3 km. 11. Route 362, from Victoria Road north to Sand Bank Road, 4.7 km. 12. Adams Road, from Trunk 10 west to end of road, 1.7 km. 13. Air Force Camp Road, from Saw Dust Road southerly to Trunk 10, 1.6 km. 14. Albany New Road, from Queens County Line northerly to end of road, 3.4 km. 15. Alden R Hubley Road, from Route 201 northerly, 0.2 km. 16. Aldred Road, from Route 221 easterly to Trunk 1, 0.8 km. 17. Alpena Road, from Inglisville Road southerly to Trunk 10, 3.4 km. -

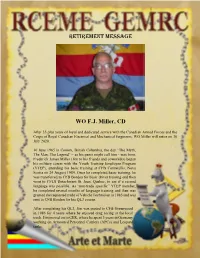

RETIREMENT MESSAGE WO F.J. Miller, CD

RETIREMENT MESSAGE WO F.J. Miller, CD After 35 plus years of loyal and dedicated service with the Canadian Armed Forces and the Corps of Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, WO Miller will retire on 30 July 2020. 10 June 1965 in Comox, British Columbia, the day “The Myth, The Man, The Legend” – as his peers might call him - was born. Frederick James Miller (Jim to his friends and coworkers) began his military career with the Youth Training Employee Program (YTEP), attending his basic training at CFB Cornwallis, Nova Scotia on 24 August 1984. Once he completed basic training, he was transferred to CFB Borden for basic driver training and then went to CFLS Detachment St. Jean, Quebec, to see if a second language was possible. As “non-trade specific” YTEP member, he completed several months of language training and then was granted the requested trade of Vehicle Technician in 1985 and was sent to CFB Borden for his QL3 course. After completing his QL3, Jim was posted to CFB Greenwood in 1986 for 4 years where he enjoyed drag racing at the local track. Jim moved on to CER, where he spent 3 years in Germany working on Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs) and Leopard tanks. Having completed a tour in former-Yugoslavia and after the shut down of CFB Lahr in 1993, was sent back to Canada. Upon his return, he was posted to Garrison Petawawa for 4 years with the Royal Canadian Dragoons (RCD). Although, this posting was not in his preferences, but he loved the tanks, Petawawa and drag racing his Mustang in Ontario and Quebec; it turned out to be a great posting after all. -

The Life and Times of WO Jack Robinson, CD

The Life and Times of WO Jack Robinson, CD WO Robinson was born and raised in Toronto, Ontario. He first joined the military in Nov 1978, went through basic training in CFB Cornwallis N.S., graduated after his 12 weeks but decided to get out after his basic (which was legal and allowed in the small print that he happen to read on his contract, this surprised his NCO’s because nobody reads the small print!). So after being out for a year and a half he felt that he had to go back and complete what he had started, so he went down to the recruiting office and joined back up, because he had completed Cornwallis, he was sent to CFB Wainwright Alberta this time to the Princes Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (P.P.C.L.I.) on the 12 November 1980. After graduating the P.P.C.L.I. battle school in April 1981 he was posted to the 3rd battalion in Victoria B.C. He was stationed in the 3rd battalion until he came across the opportunity to try out for the Jump course, so along with 60 other members of the battalion they went down to the track and ran through the PT test and came out placing 1st. They were only sending 3 members from the battalion so he earned himself a spot and was on his jump course in June 1982. He went and passed his course, came back to the battalion and was selected to be posted to the 2nd Airborne Commando in the Canadian Airborne Regiment in July 1982. -

(Military) (MSM) 1992 to 2002

MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL (Military) (MSM) 1992 to 2002 CITATIONS 1992 to 2002 UPDATED: 18 November 2020 PAGES: 61 CORRECT TO: 21 FEBRUARY 1998 CG 17 NOVEMBER 1998 CG 06 MARCH 1999 CG 05 JUNE 1999 CG 10 JULY 1999 CG 18 DECEMBER 1999 CG O1 APRIL 2000 CG 25 MAY 2000 CG 07 OCTOBER 2000 CG 03 MARCH 2001 CG 01 OCTOBER 2001 CG 14 SEPTEMBER 2002 CG =================================================================================================== CITATIONS 1992 to 2002 Page CG Name Rank Details Decorations / 38 26/04/1997 AINSLIE, Andrew Macfarlane WO SAR TECH – Night Water Parachute Jump MSM CD 22 14/05/1994 ANDERSON, Ian Wentworth Captain UNPROFOR – Firefight outside of Sarajevo MSM CD 27 03/09/1994 APPLETON, Stephen Brent Major UNPROFOR – Leadership at UNPROF HQ MSM CD 05 18/04/1992 ASHLEY, David George CPO2 Communications coordinator Gulf War MMM MSM CD 30 07/10/1995 BADANAI, Phillip Private UNPROFOR – Fire fight – drove jeep away MSM CD 31 07/10/1995 BARIL, Joseph Gerard Maurice MGen Military Advisor United Nations HQ CMM OStJ MSM CD 42 30/08/1997 BARLEE, Matthew Scott Captain Climbing Expedition with Pakistan Army MSM 44 15/11/1997 BASTIEN, Joseph Stanislas Richard Colonel Cdr 3 Wing CFB Bagotville – Flooding OMM MSM CD 05 18/04/1992 BECKETT, Jeffrey Gordon Captain Tactics Officer 439 Sqd Gulf War MSM CD 13 18/04/1992 BELISLE, Joseph Luc Guy Captain UNPROFOR – 1st Battn R22eR MB MSM CD 17 12/06/1993 BEST, Arthur Ronald Bruce Sergeant SAR TECH – Hercules rescue CFS Alert MSM 05 18/04/1992 BISSETT, Robert James MWO 439 Sqd MWO Gulf War MSM CD 32 07/10/1995 BLOUIN, Joseph Jean Paul Rejean Major UNAMIR – CO National Support Unit MSM CD 29 07/10/1995 BOUCHARD, Joseph Jocelyn Yvan Major UNPROFOR – Protect Muslims Srebrenica MSM CD 51 10/07/1999 BOWNESS, Bernard Harold Chip Colonel Cambodian Mine Action Centre Adviser MSM CD 51 10/07/1999 BRANCHAUD, Joseph Leonce Charles Major Liaison Officer Democratic Republic of Congo MSM CD 32 07/10/1995 BROMELL, David James Sergeant UNPROFOR – Keep Main Supply Route Open MSM CD 10 18/04/1992 BROUSSEAU, J.M.R. -

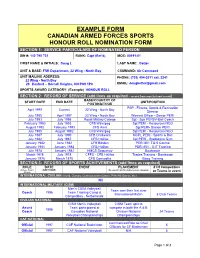

EXAMPLE CAF Honour Roll Nomination

EXAMPLE FORM CANADIAN ARMED FORCES SPORTS HONOUR ROLL NOMINATION FORM SECTION 1: SERVICE PARTICULARS OF NOMINATED PERSON SIN #: 142 790 731 RANK: Capt (Ret’d) MOC: 00191-01 FIRST NAME & INITIALS: Doug L. LAST NAME: Better UNIT & BASE: FSR Department, 22 Wing - North Bay COMMAND: Air Command UNIT MAILING ADDRESS: PHONE: (705) 494-2011 ext. 2241 22 Wing - North Bay 29 Duxford – Hornell Heights, ON P0H 1P0 EMAIL: [email protected] SPORTS AWARD CATEGORY: (Example) HONOUR ROLL SECTION 2: RECORD OF SERVICE (add lines as required – record from most to least recent) BASE/COUNTRY OF START DATE END DATE UNIT/POSITION POSTING/TOUR PSP - Fitness, Sports & Recreation April 1997 Current 22 Wing - North Bay Director July 1995 April 1997 22 Wing - North Bay Warrant Officer - Senior PERI July 1993 July 1995 Royal Military College Sgt - Sqn PERI/V-Ball Coach February 1993 July 1993 CFB Winnipeg Sgt PERI - Resources NCO August 1992 February 1993 CFS Alert Sgt PERI- Station PERI July 1990 August 1992 CFB Winnipeg Sgt PERI - Resources NCO July 1987 July 1990 CFB Chilliwack MCPL PERI - Sports & Rec July 1982 July 1987 CFB Halifax Cpl PERI - Stadacona Gym January 1982 June 1982 CFB Borden PERI 851 TQ-5 Course January 1981 January 1982 CFB Halifax PERI 851 - OJT Training July 1978 January 1981 HMCS Saguenay Boatswain March 1978 July 1978 CFFS - CFB Halifax Trades Training - Boatswain January 1978 March 1978 CFB Cornwallis Basic Training SECTION 3: RECORD OF SPORTS ACHIEVEMENTS (add lines as required) ROLE DATE EVENT PLACEMENT # Of Competitors (Athlete, Coach, -

Groundwater Resources and Hydrogeology of the Western Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia (Trescott, 1969)

PROVINCE OF NOVA SCOTIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES Groundwater Section Report 69- 1 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES AND HYDROGEOLOGY of the WESTERN ANNAPOLIS VALLEY, NOVA SCOTIA by Peter C. Trescott HON. PERCY GAUM J.P. NOWLAN, Ph.D. MIN ISTE R DEPUTY MINISTER Halifax, Nova Scotia 1969 PREFACE The Nova S coti a Department of Mines initiated in 1964 an extensive program to evaluate the groundwater resources of the Province of Nova Scotia. This report on the hydrogeology of the We s t e r n Annapolis Val ley supplements the Annapolis-Cornwallis Valley report (Department of Mines Memoir 6) by dis- cussing the groundwater resources of the area southwest of Annapolis Royal. The field work for this study was carried out during the summer of 1968 by the Groundwater Section, Nova Scotia Department of Mines, and is a joint undertaking between the Canada Department of Forestry and Rural Development and the Province of Nova Scotia (ARDA proiect No. 22042). Recently the ad- ministration of the ARDA Act was transferred to the Canada Department of Regional Economic Expansion. It should be pointed out that many individuals and other govern m e n t agencies cooperated in supplying much valuable i n f orm a t i on and assistance throughout the period of study. To list a few: Dr. J. D. Wright, Director, Geological Division and the staff of the Mineral Resources Section, Nova Scotia Department of Mines, the Nova Scotia Agricultural College at Truro, and the Nova Scotia Department ofAgriculture who made available manuscript soil maps of Annapolis County. It is hoped that information in this report will be useful for agricultural, industrial, municipal and individual water needs and that the report will serve as a guide for the future exploration, development and use of the largely un- developed groundwater resources of the Western Annapolis Val ley. -

Major Kevin Mercer, CD2 Maj Kevin Mercer Joined the Canadian Armed

Major Kevin Mercer, CD2 Maj Kevin Mercer joined the Canadian Armed Forces on 18 Nov 76 as a skilled applicant in the Construction Engineering Technician (Draftsman/Surveyor) trade. On completion of Basic Recruit Training at CFB Cornwallis for where he received the Commandant’s Shield for the Top Recruit, he proceeded to CFSME at CFB Chilliwack for TQ 3 training. His first posting was to 3 Field Squadron (later 1 CER) for a year and then on to the CFB Chilliwack CE section until 1980. Maj Mercer was married in 1980 to his beautiful wife Julie and they were immediately posted to CFS Gypsumville. Upon his return to Gypsumville from QL6A training in July 1981 he was posted to CFB Borden as the 2iC of the drafting cell. While there he was accepted into the UTPM (UTPNCM) program in Civil Engineering first at CMR St Jean and RMC Kingston in Jul 1983. Interspersed throughout the academics was the annual MILE Phase training each summer including a top student placing on Phase II. After graduation from RMC in 1988 and completion of phase training he was assigned to CFB Comox as the Engineering Officer, Planning Officer and Requirements Officer. Following this initial tour he paid his penance at Air Command Headquarters from 1992- 1997; first as the staff officer for 5 Wing, Goose Bay and 9 Wing, Gander for 3 years and then as staff officer for equipment procuring equipment for the newly formed AEFs. From Winnipeg he was posted to 22 Wing North Bay as the WCEO in 1997 maintaining operations in the NORAD Underground Complex.