Plamu Mi'kmaq Ecological Knowledge: Atlantic Salmon in Unama'ki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic Geoscience Society Abstracts 1995 Colloquium

A t l a n t ic G eo l o g y 39 ATLANTIC GEOSCIENCE SOCIETY ABSTRACTS 1995 COLLOQUIUM AND ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING ANTIGONISH, NOVA SCOTIA The 1995 Colloquium of the Atlantic Geoscience Society was held in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, on February 3 to 4, 1995. On behalf of the Society, we thank Alan Anderson, Mike Melchin, Brendan Murphy, and all others involved in the organization of this excellent meeting. In the following pages we publish the abstracts of talks and poster sessions given at the Colloquium which included special sessions on "The Geological Evolution of the Magdalen Basin: ANatmap Project" and "Energy and Environmental Research in the Atlantic Provinces", as well as contri butions of a more general aspect. The Editors Atlantic Geology 31, 39-65 (1995) 0843-5561/95/010039-27S5.05/0 40 A b st r a c t s A study of carbonate rocks from the late Visean to Namurian Mabou Group, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia T.L. Allen Department o f Earth Sciences, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3J5, Canada The Mabou Group, attaining a maximum thickness of7620 stituents of the lower Mabou Group. The types of carbonate m, lies conformably above the marine Windsor Group and rocks present include laminated lime boundstones (stromato unconformably below the fluviatile Cumberland Group. It com lites), floatstones, and grainstones. The stromatolites occur pre prises a lower grey lacustrine facies and an upper red fluviatile dominantly as planar laminated stratiform types and as later facies. The grey lacustrine facies consists predominantly of grey ally linked hemispheroids, some having a third order crenate siltstones and shales with interbedded sandstones, gypsum, and microstructure. -

Nova Scotia Inland Water Boundaries Item River, Stream Or Brook

SCHEDULE II 1. (Subsection 2(1)) Nova Scotia inland water boundaries Item River, Stream or Brook Boundary or Reference Point Annapolis County 1. Annapolis River The highway bridge on Queen Street in Bridgetown. 2. Moose River The Highway 1 bridge. Antigonish County 3. Monastery Brook The Highway 104 bridge. 4. Pomquet River The CN Railway bridge. 5. Rights River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. 6. South River The Highway 104 bridge. 7. Tracadie River The Highway 104 bridge. 8. West River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. Cape Breton County 9. Catalone River The highway bridge at Catalone. 10. Fifes Brook (Aconi Brook) The highway bridge at Mill Pond. 11. Gerratt Brook (Gerards Brook) The highway bridge at Victoria Bridge. 12. Mira River The Highway 1 bridge. 13. Six Mile Brook (Lorraine The first bridge upstream from Big Lorraine Harbour. Brook) 14. Sydney River The Sysco Dam at Sydney River. Colchester County 15. Bass River The highway bridge at Bass River. 16. Chiganois River The Highway 2 bridge. 17. Debert River The confluence of the Folly and Debert Rivers. 18. Economy River The highway bridge at Economy. 19. Folly River The confluence of the Debert and Folly Rivers. 20. French River The Highway 6 bridge. 21. Great Village River The aboiteau at the dyke. 22. North River The confluence of the Salmon and North Rivers. 23. Portapique River The highway bridge at Portapique. 24. Salmon River The confluence of the North and Salmon Rivers. 25. Stewiacke River The highway bridge at Stewiacke. 26. Waughs River The Highway 6 bridge. -

South Western Nova Scotia

Netukulimk of Aquatic Natural Life “The N.C.N.S. Netukulimkewe’l Commission is the Natural Life Management Authority for the Large Community of Mi’kmaq /Aboriginal Peoples who continue to reside on Traditional Mi’Kmaq Territory in Nova Scotia undisplaced to Indian Act Reserves” P.O. Box 1320, Truro, N.S., B2N 5N2 Tel: 902-895-7050 Toll Free: 1-877-565-1752 2 Netukulimk of Aquatic Natural Life N.C.N.S. Netukulimkewe’l Commission Table of Contents: Page(s) The 1986 Proclamation by our late Mi’kmaq Grand Chief 4 The 1994 Commendation to all A.T.R.A. Netukli’tite’wk (Harvesters) 5 A Message From the N.C.N.S. Netukulimkewe’l Commission 6 Our Collective Rights Proclamation 7 A.T.R.A. Netukli’tite’wk (Harvester) Duties and Responsibilities 8-12 SCHEDULE I Responsible Netukulimkewe’l (Harvesting) Methods and Equipment 16 Dangers of Illegal Harvesting- Enjoy Safe Shellfish 17-19 Anglers Guide to Fishes Of Nova Scotia 20-21 SCHEDULE II Specific Species Exceptions 22 Mntmu’k, Saqskale’s, E’s and Nkata’laq (Oysters, Scallops, Clams and Mussels) 22 Maqtewe’kji’ka’w (Small Mouth Black Bass) 23 Elapaqnte’mat Ji’ka’w (Striped Bass) 24 Atoqwa’su (Trout), all types 25 Landlocked Plamu (Landlocked Salmon) 26 WenjiWape’k Mime’j (Atlantic Whitefish) 26 Lake Whitefish 26 Jakej (Lobster) 27 Other Species 33 Atlantic Plamu (Salmon) 34 Atlantic Plamu (Salmon) Netukulimk (Harvest) Zones, Seasons and Recommended Netukulimk (Harvest) Amounts: 55 SCHEDULE III Winter Lake Netukulimkewe’l (Harvesting) 56-62 Fishing and Water Safety 63 Protecting Our Community’s Aboriginal and Treaty Rights-Community 66-70 Dispositions and Appeals Regional Netukulimkewe’l Advisory Councils (R.N.A.C.’s) 74-75 Description of the 2018 N.C.N.S. -

In the Saint John River, New Brunswick

RESTORATION POTENTIAL FOR REPRODUCTION BY STRIPED BASS (Morone saxatilis) IN THE SAINT JOHN RIVER, NEW BRUNSWICK by Samuel Nelson Andrews Previous Degrees (BSc, Dalhousie, 2012) (MSc, Acadia University, 2014) A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Academic Unit of Biology Supervisors: R. Allen Curry, Ph.D., Biology, FOREM, and CRI Tommi Linnansaari, Ph.D., Biology, FOREM, and CRI Examining Board: Mike Duffy, Ph.D., Biology, UNB Scott Pavey, Ph.D., Biology, UNBSJ Tillmann Benfey, Ph.D., Biology, UNB External Examiner: Roger A. Rulifson, Ph.D., Biology/Fisheries and Fish Ecology, Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences, East Carolina University This dissertation is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK December 2019 © Samuel Nelson Andrews, 2020 Abstract In 2012 the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) listed the Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis) of the Saint John River, New Brunswick, as endangered as part of the Bay of Fundy designatable unit. This listing was due to an apparent rapid collapse and subsequent absence of presumed native origin Striped Bass, juvenile recruitment, and spawning by the species following the completion of the large Mactaquac Dam in 1968. Expert reports hypothesized that alteration in the river flow and temperature regime imposed upon the Saint John River downstream from the Mactaquac Dam were responsible for the disappearance, however, no recovery efforts or exploratory studies were conducted, and the native Striped Bass population was deemed extinct. This dissertation explored the collapse of the Saint John River Striped Bass starting with a complete historic perspective of the species in the Saint John River and concluded with a possible means to recover the population that was once believed to be lost. -

Recovery Potential Assessment for Eastern Cape Breton Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar): Habitat Requirements and Availability; and Threats to Populations

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2014/071 Maritimes Region Recovery Potential Assessment for Eastern Cape Breton Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar): Habitat Requirements and Availability; and Threats to Populations A.J.F. Gibson, T.L. Horsman, J.S. Ford, and E.A. Halfyard Fisheries and Oceans Canada Science Branch, Maritimes Region P.O. Box 1006, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Canada, B2Y 4A2 December 2014 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Research documents are produced in the official language in which they are provided to the Secretariat. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Gibson, A.J.F., Horsman, T., Ford, J. and Halfyard, E.A. 2014. Recovery Potential Assessment for Eastern Cape Breton Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar): Habitat requirements and availability; and threats to populations. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2014/071. vii + 141 p. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................ -

J)L () Ihis Report Not to Be Quoted Without Prior Referenee to the Couneil*

-.. , J)l () Ihis report not to be quoted without prior referenee to the Couneil* International Couneil for the C.M.1990/M:4 Exploration of the Sea Anadromous and Catadromous Fish Committee ICES COHPlLATIDN OF HICROTAG. FINCLIP. AND EXTERNAL TAG RELEASES IN 1989 Ihis doeument is areport of a Working Group of the International Gouneil for the Exploration of the Sea and does not neeessarily represent the views of the Couneil. Iherefore, it should not be quoted without eonsultation with the General Seeretary. *General Seeretary leES Pal<egade 2-4 DK-1261 Copenhagen K DENMARK < i > TAB LE o F C 0 N T E N T S Page Terms of Reference •...•.•.••..••••.•.. Table 2 APPENDIX 1, List of national tag clearing houses to which Atlantic salmon tags should be returned for verification ••.•.•••.•.•••.•• 3 • ICES ATLANTIC SALMON MARKING DATA BASE, Canada ••.. 4 Faroe Islands 21 France . 22 Iceland 23 Ireland 35 Norway 37 Sweden (West Coast) 39 UR (England and Wales) 40 UK (Scotland) 46 UR (N. Ireland) 52 USA 53 USSR 59 • ---00000--- Terms of reference for the 1990 leES North Atlantic Salmon Work ing Group state that the Group should: "With respect to Atlantic salmon in the NAseo area, prepare a compi~ation of microtag. finc1ip, and exter nal tag releases within leES member countries in 1989". Data were provided by Working Group members tor national tagging programmes, as far as possible including all agencies and organ izations. These compilation data are presented by country, together with a summary of the tags and tinclips applied by all countries (Table 1). -

DCBA Winter Product Proposal

26 Brandy Point Road Grand Bay-Westfield, N.B. Canada E5K 2W6 Tel: 506.217-0110 www.tourismsynergy.ca CAPE BRETON ISLAND WINTER PRODUCT SITUATION ANALYSIS, INVENTORY and OPPORTUNITIES ASSESSMENT Prepared for by Tourism Synergy Ltd. Revised May 4, 2016 24 Sunset Crescent Grand Bay-Westfield NB Canada E5K 2W4 Tel: 506.217.0110 www.tourismsynergy.com Cape Breton Island Winter Product Situation Analysis, Inventory & Opportunities Assessment ii CONTENTS Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………… iv 1. Introduction……………….………….………………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. Purpose and Objectives…………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 3. Approach ………………………….…..……………………………………………………………………………… 2 4. Winter Product Situation Analysis……………………………………………................................ 2 4.1 Atlantic Canada Winter Tourism and Activities.…………………………………………….. 2 4.2 Nova Scotia Winter Product..……………………………………………………………………...... 3 4.3 New Brunswick Winter Product..…………………………………………………………………… 8 4.4 Newfoundland and Labrador………………………………………………………………………… 9 4.5 Prince Edward Island…………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 5. Market Readiness Criteria…………………………………….................................................... 12 6. CBI Winter Tourism Product/Experience Inventory………………………………………………… 14 6.1 CBI Winter Accommodations………………………………………………………………………. 14 6.2 Food & Beverage Establishments/Restaurants……………………………………………. 17 6.3 Outdoor Activities……………………………………………………………………………………….. 19 6.3.1 Non-motorized Activities…………………………………………………………………. 19 6.3.2 Motorized Activities………………………………………………………………………… -

Chemical Characteristics of Selected Cape Breton Rivers, 1985 Canadian Data Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences No

08000530 Chemical Characteristics of Selected Cape Breton Rivers, 1985 D. K. MacPhail. D. Ashfield and G.J. Farmer Enhancement, Culture and Anadromous Fisheries Division Biological Sciences Department of Fisheries and Oceans Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3J 2S7 . June, 1987 Canadian Data Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences No. 654 Canadian Data Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Data reports provide a medium for filing and archiving data compilations where little or no analysis is included. Such compilations commonly will have been prepared in support of other journal publications or reports. The subject matter of data reports reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. namely. fisheries and aquatic sciences. Data reports are not intended for generill distribution and the contents must not be referred to in other publications without prior written authoriziltion from the issuing establishment. The COITect citation appears ilbove the abstract of each report. Data reports are abstracted in A qualie Sciellces alld Fisheries A bS/roclS and indexed in the Department's ilnnual index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-25 in this series were issued as Fisheries and Marine Service Data Records. Numbers 26-160 were issued as Department of Fisheries and the Environ ment. Fisheries and Marine Service Data Reports. The current series name was intro duced with the publication of report number 161. Data reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Out-of-stock reports will be supplied for a fee by commerciill ilgents. -

T8.1 Freshwater Hydrology ○

PAGE .............................................................. 150 ▼ T8.1 FRESHWATER HYDROLOGY ○ Nova Scotia has no shortage of fresh water. The total Limnology and hydrogeology are specialized mean precipitation is fairly high: approximately 1300 branches of hydrology. Limnology is the study of sur- mm as compared to 800–950 mm in central Ontario face freshwater environments and deals with the rela- and 300–400 mm in southern Saskatchewan. Fre- tionships between physical, chemical, and biological quent coastal fog, cloudy days and cool summers components. Hydrogeology is the study of ground- combine to moderate evapotranspiration. The re- water, emphasizing its chemistry, migration and rela- sult is a humid, modified-continental climate with a tion to the geological environment.1 moisture surplus. Large areas of impermeable rock and thin soils and the effect of glaciation have influ- THE HYDROLOGIC CYCLE enced surface drainage, resulting in a multitude of bogs, small lakes and a dense network of small The continuous process involving the circulation of streams. Groundwater quality and quantity vary ac- water between the atmosphere, the ocean and the cording to the type of geology in different parts of the land is called the hydrologic cycle (see Figure T8.1.1). province. The following topics describe the cycle of Solar radiation and gravity are the driving forces that water and the various environments and forms in “run” the cycle. which it manifests itself. Fresh water as a resource is As water vapour cools, condensation occurs and discussed in T12.8. clouds form. When rain or snow falls over land, a number of things can happen to the precipitation: ○○○○○○○○ some of it runs off the land surface to collect in catchment basins, some is returned directly to the Hydrology is the study of water in all its forms and atmosphere by evaporation and by transpiration T8.1 its interactions with the land areas of the earth. -

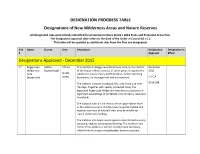

DESIGNATION PROGRESS TABLE Designations of New Wilderness Areas and Nature Reserves

DESIGNATION PROGRESS TABLE Designations of New Wilderness Areas and Nature Reserves All designated sites were initially identified for protection in Nova Scotia’s 2013 Parks and Protected Areas Plan. The designation approval date refers to the date of the Order in Council (O.I.C.). This table will be updated as additional sites from the Plan are designated. Site Name County Area Description Designation Designation in # Approval Effect Designations Approved - December 2015 17 Boggy Lake Halifax, 973 ha This addition to Boggy Lake Wilderness Area, in the interior December Wilderness Guysborough of the Eastern Shore, consists of seven parts. It expands the 2015 Area (2,405 wilderness area to nearly 4,700 hectares, while improving (expansion) acres) boundaries for management and enforcement. O.I.C.# The addition includes hardwood hills, lake shore and river 2015-388 frontage. Together with nearby protected lands, the expanded Boggy Lake Wilderness Area forms a provincially- significant assemblage of protected river corridors, lakes and woodlands. The addition adds a 9 km section of the upper Moser River to the wilderness area. It helps protect aquatic habitat and expands corridors of natural forest used by wildlife for travel, shelter and feeding. The addition also helps secure opportunities for backcountry canoeing, angling, camping and hunting. The northern two- thirds of the addition is within Liscomb Game Sanctuary, which limits hunting to muzzleloader, bow or crossbow. Site Name County Area Description Designation Designation in # Approval Effect Forest access roads along the western and northern sides of the addition provide access. Vehicle use to access points at Long Lake and Bear Lake is also unaffected. -

Ecological Landscape Analysis of Cape Breton Coastal Ecodistrict 810 40

Ecological Landscape Analysis of Cape Breton Coastal Ecodistrict 810 40 © Crown Copyright, Province of Nova Scotia, 2015. Ecological Landscape Analysis, Ecodistrict 810: Cape Breton Coastal Prepared by the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources Authors: Eastern Region DNR staff ISBN 978-1-55457-604-3 This report, one of 38 for the province, provides descriptions, maps, analysis, photos and resources of the Cape Breton Coastal Ecodistrict. The Ecological Landscape Analyses (ELAs) were analyzed and written from 2005 – 2009. They provide baseline information for this period in a standardized format designed to support future data updates, forecasts and trends. The original documents are presented in three parts: Part 1 – Learning About What Makes this Ecodistrict Distinctive – and Part 2 – How Woodland Owners Can Apply Landscape Concepts to Their Woodland. Part 3 – Landscape Analysis for Forest Planners – will be available as a separate document. Information sources and statistics (benchmark dates) include: • Forest Inventory (1995 to 1997) – stand volume, species composition • Crown Lands Forest Model landbase classification (2006) – provides forest inventory update for harvesting and silviculture from satellite photography (2005), silviculture treatment records (2006) and forest age increment (2006) • Roads and Utility network – Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations (2006) • Significant Habitat and Species Database (2007) • Atlantic Canada Data Conservation Centre (2013) Conventions Where major changes have occurred since the -

Fauna of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada: New Records, Distributions, and Faunal Composition

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 897: 49–66 (2019) The Hydradephaga of Cape Breton Island 49 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.897.46344 CHECKLIST http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The Hydradephaga (Coleoptera, Haliplidae, Gyrinidae, and Dytiscidae) fauna of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada: new records, distributions, and faunal composition Yves Alarie1 1 Department of Biology, Laurentian University, Ramsey Lake Road, Sudbury, ON P3E 2C6, Canada Corresponding author: Yves Alarie ([email protected]) Academic editor: M. Michat | Received 5 September 2019 | Accepted 12 November 2019 | Published 9 December 2019 http://zoobank.org/DEA12DCE-1097-4A8C-9510-4F85D3942B10 Citation: Alarie Y (2019) The Hydradephaga (Coleoptera, Haliplidae, Gyrinidae, and Dytiscidae) fauna of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada: new records, distributions, and faunal composition. ZooKeys 897: 49–66. https:// doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.897.46344 Abstract The Haliplidae, Gyrinidae, and Dytiscidae (Coleoptera) of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada were surveyed during the years 2006–2007. A total of 2027 individuals from 85 species was collected from 94 different localities, which brings to 87 the number of species recorded for this locality. Among these, Heterosternuta allegheniana (Matta & Wolfe), H. wickhami (Zaitzev), Hydroporus appalachius Sherman, H. gossei Larson & Roughley, H. nigellus Mannerheim, H. puberulus LeConte, Ilybius picipes (Kirby), and I. wasastjernae (C.R. Sahlberg) are reported for the first time in Nova Scotia. The Nearctic component of the fauna is made up of 71 species (81.6%), the Holarctic component of 16 species (18.4%). Most species are characteristic of both the Boreal and Atlantic Maritime Ecozones and have a transcontinental distribution but 19 species (21.8%), which are generally recognized as species with eastern affinities.