1 Features of Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 Client/Matter: -None- 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived

Dr. Sunita B. Nimavat [Subject: English] International Journal of Vol. 2, Issue: 4, April-May 2014 Research in Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived DR. SUNITA B. NIMAVAT N.P.C.C.S.M. Kadi Gujarat (India) Abstract: In my research paper, I am going to discuss the great, creative journalist & author Khushwant Singh. I will discuss his views and reflections on retirement. I will also focus on his reflections regarding journalism, writing, politics, poetry, religion, death and longevity. Keywords: Controversial, Hypocrisy, Rejects fundamental concepts-suppression, Snobbish priggishness, Unpalatable views Khushwant Singh, the well known fiction writer, journalist, editor, historian and scholar died at the age of 99 on March 20, 2014. He always liked to remain controversial, outspoken and one who hated hypocrisy and snobbish priggishness in all fields of life. He was born on February 2, 1915 in Hadali now in Pakistan. He studied at St. Stephen's college, Delhi and king's college, London. His father Shobha Singh was a prominent building contractor in Lutyen's Delhi. He studied law and practiced it at Lahore court for eight years. In 1947, he joined Indian Foreign Service and worked under Krishna Menon. It was here that he read a lot and then turned to writing and editing. Khushwant Singh edited ‘ Yojana’ and ‘ The Illustrated Weekly of India, a news weekly. Under his editorship, the weekly circulation rose from 65000 copies to 400000. In 1978, he was asked by the management to leave with immediate effect. -

U.O.No. 5868/2017/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 10.05.2017

File Ref.No.26046/GA - IV - E - SO/2016/Admn UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract Faculty of Commerce and Management studies-Revised Regulations, Scheme and Syllabus of Bachelor of Commerce(BCom) Degree Programme under CUCBCSS UG-with effect from the 2017-18 admission-implemented- orders issued. G & A - IV - E U.O.No. 5868/2017/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 10.05.2017 Read:-1.Item No..1 of the Minutes of the meeting of the Board of Studies in Commerce(UG) held on 02.02.2017. 2.Item No.2 of the Minutes of the meeting of the Faculty of Commerce and Management Studies held on 29.03.2017. ORDER As per paper read as (1) above, the meeting of the Board of Studies in Commerce (UG) held on 02.02.2017, resolved to approve and adopt the revised Regulation, Scheme and syllabus of B.Com (CUCBCSS) with effect from the academic year 2017-18. As per paper read as (2) above, the Faculty of Commerce and Management Studies approved the minutes of the Board of Studies in Commerce (UG) read as (1) above. After considering the matter in detail, the Hon'ble Vice Chancellor has accorded sanction to implement the revised Regulation, Scheme and Syllabus of B.Com (CUCBCSS) with effect from 2017-18 admission onwards, subject to ratification by the Academic Council. The following orders are therefore issued; The revised Regulation, Scheme and Syllabus of B.Com (CUCBCSS) is implemented with effect from 2017-18 admission, subject to ratification by the Academic Council. (Revised Regulation, scheme and syllabus appended) Vasudevan .K Assistant Registrar To 1.Principal of all affiliated Colleges offering B.Com programme 2.Controller of Examinations Copy to: PS to VC/PA to PVC/PA to Registrar/PA to CE/J.R, B.Com branch/Digital wing/EX & EG section/SF/DF/FC. -

The Gazette of India

REGISTERED No. D. 221 The Gazette of India EXTRAORDINARY PART I—Section 1 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 21] NEW DELHI, FRIDAY, JANUARY 26, I973/MAGHA 6, 1894 Separate paging is given to this Part in order that it may be filed as a separate compilation PRESIDENT'S SECRETARIAT NOTIFICATION New Delhi, the 26th January 1973 No, 8-Pres/73.—The President is pleased to make the following awards:— PADMA VIBHUSHAN Shrimati Basanti Devi, Freedom Fighter, Calcutta. Dr. Daulat Sinyh Kothari Formerly Chairman, University Grants Commission, New Delhi. Dr. Nagendra Singh, Formerly Secretary to the President and now Chief Elec- tion Commissioner, New Delhi. Shrimati Nellie Sen Gupta, Freedom Fighter, Calcutta. Shri Thirumalraya Swaminathan, Formerly Cabinet Secretary. Government of] India, New Delhi. Shri Uchhrangrai Navalshankar Dhebar, Constructive Worker, Rajkot, Gujarat. PADMA BHUSHAN Shri Bannrsi Dass Chaturvedi, Journalist and Author, Uttar Pradesh. Shri Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavathar, Musician, Madras. Shrimati Gosasp Maneekji Sorabji Captain, Freedom Fighter, Bombay. Shri Harindranath Chattopadhyaya, Litterateur, Bombay, Shri Krishna Rao Shankar Pandit, Musician, Madhya Pradesh, ( 75 ) 76 nil; UAZiaTE 01- 1NDJA HX IKAORDlFMRY [PART I—SEC. \[ Shri Kunjuraman Suluirnar;in, Managing Ed'tloc, Kor;ila Kaumudi, Trivandium. Shri Maqbool Fida Hnsuiu, Painter, Nevv Delhi. Shri Naraindas RatUnmal IVIalkani, Social Worker, Gujarat. Dr. Om P. Balil, Professor u: Biochemistry, University of Buttalo, New Itork. Shri Pitambar Punt, Chairman, National Committee on Environmental Planning and Co-ordination, New Delhi. Shri Pothen Joseph, Journalist. (Postlivmou:<)- Dr. Raja Muthiah AnnrimnJal Muthiah Che:tiar, Industrialist, Tamil Nadu. Dr. Haja Ramanna, Director, Bhabha AIOLI.C Research Centre and Member, Research and Development, Ai.on.ik1 Energy Commission, 3<>mha,v. -

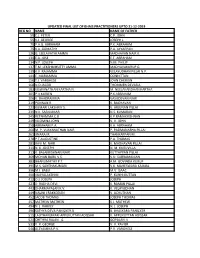

Reg No Name Name of Father 50 C.J. Peter C.P. John 55 K.J. George Joseph J

UPDATED FINAL LIST OF BHMS PRACTITIONERS UPTO 31-12-2019 REG NO NAME NAME OF FATHER 50 C.J. PETER C.P. JOHN 55 K.J. GEORGE JOSEPH J. 70 P.A.G. ABRAHAM P.K. ABRAHAM 75 K.A. GOMATHY P.A. AYYAPPAN 126 G. LEELAVATHI AMMA MADHAVAN NAIR K. 131 E.A. JOSE E.T. ABRAHAM 134 N.P. JOSEPH N.M. PHILIP 137 T.M. LEKSHMIKUTTY AMMA MADHAVAKURUP G. 139 K.V. RAJAMMA VELAYUDHAN PILLAI N.P. 141 E. MARIAMMA OONNITTAN 156 T.J. VARGHESE JOHN CHERIAN 168 N.D.JACOB THOMMEN DEVASIA 183 VISWANATHAN KARTHA N. M. NEELAKANDHAN KARTHA 205 P.A.KURIEN P.K.ABRAHAM 206 V. BHADRAMMA VASUDEVAN NAIR 219 PONNAN R. K. RAGHAVAN 223 KUMARI LAKSHMY S. V. ARJUNAN PILLAI 235 N.K. SASIKUMAR N.S. KUMARAN 245 RETNAMMA.C.B K.P.RAMAKRISHNAN 249 VILOMINA JOHN V. V. JOHN 258 ABRAHAM P.A. K.A. ABRAHAM 260 M. P. VIJAYANATHAN NAIR P. PADMANABHA PILLAI 261 JINARAJ R. THANKAPPAN M. 278 P.T.AUGUSTINE P.A. THOMAS 281 RAVI M. NAIR K. MADHAVAN PILLAI 311 N. K. JOSEPH N. M. KURUVILLA 313 K. BALAKRISHNAN NAIR KUTTAPPAN PILLAI 369 MOHAN BABU V.S. V.U. SUBRAMANIAN 383 BHANUMATHY P.T. A.M. GOVINDA KURUP 395 M.S. SANTHAKUMARI V.K. MAHESWARA KAIMAL 396 M.I. BABU M.V. ISAAC 400 VIJAYALAKSHMI P. KUNHI KUTTAN 412 O.J. JOSEPH JOSEPH 423 D. RADHA DEVI K. RAMAN PILLAI 443 DHARMAPALAN K.V. K. VELAYUDHAN 449 NALINI ERAKKODAN V. ACHUTHAN 452 JACOB THOMAS JOSEPH THOMAS 457 MATHEW MATHEW K.J. -

Mainstreaming Mental Illness Is Long Overdue

A JOURNAL OF THE PRESS INSTITUTE OF INDIA ISSN 0042-5303 January-March 2021 Volume 13 Issue 1 Rs 60 Mainstreaming mental illness is long overdue CONTENTS • For institutionalised children, it’s a In January this year, Future Generali India Insurance came up long battle / Rina Mukherji with a series of advertisements on mental health issues. The • Away from school, where the mind ads made a lot of viewers sit up, especially those in families savours each moment / Janani Murali • Making a case for climate activism / having to take care of a member suffering from mental health Bharat Dogra issues, says Manjira Mazumdar. Mainstreaming health issues • Creating awareness silently / is long called for, and the media can play a huge role in it, she Sayanika Dutta says • Profiteering even from a pandemic / Sakuntala Narasimhan here is no insurance for patients hospitalised due to mental ill- • The environmental impacts of nesses. Outpatient department patients usually are covered, only if the economic package / S. Gopikrishna Warrier the OPD benefit clause includes counseling and therapy. However, T • Has the private sector failed with COVID-19, there was a marked increase in people suffering from to live up to expectations? / anxiety and depression. This led to Insurance Regulatory and Develop- N.S. Venkataraman ment Authority (IRDAI) instructing health insurance companies cover • Healthy discussions, impressive policy holders who are mentally ill – those who resort to opiods and anti- sales, more committed readers / depressants due to clinical depression, or any other neurodegenerative or Nava Thakuria psychiatric disorders. • Longest running English journal in India celebrates 125 / But how many people in India talk about mental health? It is not at all Mrinal Chatterjee an easy matter to deal with because of the several grey areas, which cannot • A look at the representation of be defined as in physical health issues. -

Profiles in Courage : Dissent on Indian Socialism

Profiles In Courage: Dissent on Indian Socialism Parth J Shah Edited by CENTRE FOR CIVIL SOCIETY B-12, Kailash Colony New Delhi-110048 Phone: 646 8282 Fax: 646 2453 E-mail: [email protected] Edited by Parth J Shah Website: www.ccsindia.org Rs. 350 CCS Profiles In Courage Dissent on Indian Socialism Edited by Parth J Shah CENTRE FOR CIVIL SOCIETY Centre for Civil Society, December 2001 All rights reserved. ISBN: 81-87984-01-5 Published by Dr Parth J Shah on behalf of Centre for Civil Society, B-12, Kailash Colony, New Delhi - 110 048. Designed and printed by macro graphics.comm pvt. ltd., New Delhi - 110 019 Table of Contents Introduction i Parth J Shah Minoo Masani: The Making of a Liberal 1 S V Raju Rajaji: Man with a Mission 33 G Narayanaswamy N G Ranga: From Marxism to Liberalism 67 Kilaru Purna Chandra Rao B R Shenoy: The Lonely Search for Truth 99 Mahesh P Bhatt Piloo Mody: Democracy with Bread and Freedom 109 R K Amin Khasa Subba Rau: Pen in Defence of Freedom 135 P Vaman Rao A D Shroff: The Liberal and the Man 159 Minoo Shroff About the Contibutors 179 179 About the Contributors R K Amin Professor R K Amin was born on June 24, 1923, in Ahmedabad district in Gujarat. He holds a BA (Hons) and MA from Bombay University and a BSc and MSc in economics from the London School of Economics and Political Science. Professor Amin started his career as a Professor of Economics at the L D College of Arts in Gujarat University and then worked as Principal of a commerce college affiliated to Sardar Patel University at Vallabh Vidyanagar. -

1. Letter to Additional Secretary, Home Department, Government of India

1. LETTER TO ADDITIONAL SECRETARY, HOME DEPARTMENT, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DETENTION CAMP, January 27, 1944 ADDITIONAL SECRETARY TO THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA (HOME DEPARTMENT) NEW DELHI SIR, Some days ago Shri Kasturba Gandhi told the Inspector-General of prisons and Col. Shah that Dr. Dinshaw Mehta of Poona be invited to assist in her treatment. Nothing seems to have come out of her request. She has become insistent now and asked me if I had written to the Government in the matter. I, therefore, ask for immediate permission to bring in Dr. Mehta. She has also told me and my son that she would like to have some Ayurvedic physician to see her.1 I suggest that the I.G.P. be authorized to permit such assistance when requested. 2. I have no reply as yet to my request2 that Shri Kanu Gandhi, who is being permitted to visit the patient every alternate day, be allowed to remain in the camp as a whole-time nurse. The patient shows no signs of recovery and night-nursing is becoming more and more exacting. Kanu Gandhi is an ideal nurse, having nursed the patient before. And what is more, he can soothe her by giving her instrumental music and by singing bhajans. I request early relief to relieve the existing pressure. The matter may be treated as very urgent. 3. The Superintendent of the camp informs me that when visitors come, one nurse only can be present. Hitherto more than one nurse has attended when necessary. The Superintendent used his discretion as to the necessity. -

Fy 2000-2001

NAME OF ENTITLED SHAREHOLDER LAST KNOWN ADDRESS NATURE OF AMOUNT ENTITLED DATE OF AMOUNT (Rs.) TRANSFER TO IEPF PRADIP DEWAL PADMAKAR State Bank Of Travancore 125 M G Road Fort Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 150.00 19-Jan-2021 Mumbai Mumbai 400023 SBT for FY 2000-2001 KUMARI SINDHU R Cashier/clerk State Bank Of Travancore 125 M G Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 300.00 19-Jan-2021 Road Fort Mumbai Mumbai 400023 SBT for FY 2000-2001 RAJAN CHANDRASEKHARAN Asst Manager State Bank Of Travancore Mumbai Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 600.00 19-Jan-2021 Main Branch Mumbai 400001 SBT for FY 2000-2001 RONALD J MASTERLY State Bank Of Travancore Mumbai Main Mumbai Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 600.00 19-Jan-2021 400023 SBT for FY 2000-2001 KANAKARAN P Sbt Chennai Main 600108 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 150.00 19-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2000-2001 AMUDHAVALLY N 5/581 Moogappair Madras 600050 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 150.00 19-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2000-2001 GANESAN V Plot No 18 Vyasar Street Chitlapakkam Chennai Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 300.00 19-Jan-2021 Chennai 600054 SBT for FY 2000-2001 ARAVINDAN M P Deputy Manager Sbt Ooty 693001 Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 600.00 19-Jan-2021 SBT for FY 2000-2001 JEGANATHAN G 30 Krishnarajapuram St Pappanaicken Palayam Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 150.00 19-Jan-2021 Coimbatore 641037 SBT for FY 2000-2001 GIRIJAMENON K P State Bank Of Travancore Coimbatore Main Unclaimed and unpaid dividend of 150.00 19-Jan-2021 641001 SBT for FY 2000-2001 RAGUNATHAN S 28 Jesurathinam St C S I School -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue No. 13 Of The Papers of Gopalkrishna Gandhi Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Gopalkrishna Gandhi A diplomat and renowned academic, Gopalkrishna Gandhi was born on 22 April 1945. He is a grandson of Mahatma Gandhi. After graduating from St. Stephen‟s College, Delhi, he joined the Indian Civil Services in 1968 and served in Tamil Nadu till 1985. He served as Secretary to the Vice-President of India (1985-1987) and Joint Secretary to the President of India (1987-1992). Gopalkrishna Gandhi took voluntary retirement from the IAS in 1992. He set up the Nehru Centre in London for Indo-British collaboration in cultural, literary and academic fields and was its Director(1992-1996). He served as High Commissioner of India to South Africa and Lesotho (1996), Secretary to President of India (1997-2000), High Commissioner of India to Sri Lanka (2000), Ambassador of India to Norway and Iceland (2002), and Governor of West Bengal (2004- 2009). He was given the additional charge of the Governor of Bihar for a few months in 2006. Gopalkrishna Gandhi was Chairman of the Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla and Kalakshetra Foundation, Chennai (2011-2014). He received the Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Award of the University of Mysore in 2016, the Lal Bahadur Shastri Award in 2016 and the Rajiv Gandhi Sadbhavana Award in 2018. He received honorary degrees from the University of Natal, South Africa (1999), University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka (2001), University of North Orissa, India (2012),and University of Calcutta, India (2019). -

Ac Name Ac Name2 Ac Addr1 Ac Addr2 Ac Addr3

AC_NAME AC_NAME2 AC_ADDR1 AC_ADDR2 AC_ADDR3 ALEXANDER V J VAIKATHUKARAN HOUSEALAPPUZHA VYSAKH S S REP BY MOTHER VANAJAATTIYIL P HOUSE PATHIRAPPALLY (P.O), ALAPPUZHA ABDUL NAZAR K H (DR) KAROTHUKUZHI HOUSEASOKAPURAM ALUVA ABDUL REHIMAN K M ERUMATHALA P O CHOONDI ABDUL SALAM C A CHENNAMPILLY NEMBARIPARAMBU THAIKATTUKARA ALUVA ADMINISTRATOR (SR) CARMAL HOSPITAL ALUVA ALPHONSA T K CSB LTD ANGAMALY ANGAMALY BR ALPI KURIAKOSE CSB LTD M G ROAD ERNAKULAM AMMINI SEBASTIAN . ANTO A E CSB LTD STAFF ANTONY CHERIAN P . ANTONY D PARACKAL CHENGAL KALADY P O PIN 683 574 ASHA DINESH . AUGUSTINE VALLURAN (FR) . BABU R .. BABU VIJAYALAKSHMI (DR) . BABY K O CSB LTD ALUVA BR BENNY PAUL (DR) . BINDU ALAPPAT EDATTUKARAN HOUSETHAIKATTUKARA P O ALUVA 6 DAIS ALAPATT . ELSY M . EMILI MATHEW AMBATTU H U C COLLEGE P O ALUVA FAIZAL V E VADACKANETHIL HOUSECHALACKAL MARAMPILLYALUVA P O 7 PIN 683 107 FRANCIS K P ANTO FRANCIS & ANTONY. FRANCIS FRANCIS K V PEARL FRANCIS . FRANCIS P J MANAGER CSB LTD GEORGE J PYNADATH . PYNADATHU HOUSE CHALAKUDY P O GEORGE XAVIER . GEORGE XAVIER . IBRAHIMKUTTY K M EDAYATTIL PALLOTH HOUSEEDAYAPURAM IGNATIOUS M STAFF CSB LTD NAGERCOIL ISSAC THARAKAN C G (DR) . JAMEELA JAMEELA NIVAS NAZRETH. RD ALUVA JAMES J DAVID PERAKKAT HOUSE BRIDGE ROAD ALUVA JAYAPRAKASH K P V/470 LAKSHMI JYOTHIOCHERI JUNCTION ALUVA JOHNY URMISE . JOICY CHOORACKAL JOHNSON NALUKETT P O KORATTY PIN 683 589 JOSE T PAUL . JOSEPH ABRAHAM P PUTHENPURAKKAL HSPANAMPILLY COCHIN 6 JOSEPH BABY ASSIST MANAGER NEEZHOOR BR JOSEPH C J THE CATHOLIC SYRIANALUVA BANK BR.LTD JOSEPH FRANCIS . JOSEPH P V PAYYAPPILLY HOUSE VATTAPARAMBU PO PIN 683 579 JOSEPH RAJAN . -

Being Salman the Dangerous Innocence of Bollywood’S Most Controversial Superstar Anna Mm Vetticad

Founder: Vishva Nath (1917-2002) VOLUME 09 • ISSUE 11 Editor-in-Chief, Publisher & Printer: Paresh Nath NOVEMBER 2017 cover story 20 Being Salman The dangerous innocence of Bollywood’s most controversial superstar anna mm vetticad Salman Khan has appeared in some of the biggest blockbusters in Hindi film history. But his career has been blighted by allegations of involvement in crimes of poaching, domestic violence and culpable homicide. In the last decade, the star has tried to reform his image. If he has succeeded to some extent, it has been not just through his own efforts, but also the willingness of his fans and many around him to accept or justify even his most disturbing behaviour. 20 perspectives 17 48 62 politics 14 Hammer and Fickle 48 The Second Coming Nepali politics sees a major reconfiguration How Malayalam cinema’s only female superstar got back to work in time for a watershed election leena gita reghunath shubhanga pandey 62 Director’s Cut 17 Counting Crores The cinematic myth-making of Louis Mountbatten Why Indian films’ box-office figures do not add up manik sharma suprateek chatterjee NOVEMBER 2017 3 the lede 72 12 arts 8 People’s Choice Attendance and absence at the Tibetan photo essay / health Music Awards 72 Deadly Risk aathira konikkara Unsafe abortions through the ages politics laia abril 12 Driving Miss Jinnah An antique car exhibit in Karachi spotlights an underappreciated historical figure alizeh kohari books 94 literature 86 The Streets of Desire Old Delhi’s subversive love-letter manuals kanupriya dhingra 86 the bookshelf 92 showcase 94 NOTE TO READERS: “A MARKETING INITIATIVE” ON PAGES 42–46 AND “SPONSORED FEATURE” ON editor’s pick 98 PAGES 60–61 AND 70–71 ARE PAID ADVERTISING CONTENT.