Developing and Using the Concept of Operations in Transportation Management Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20-24 Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan

Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan Final Report | Report Number 20-24 | August 2020 NYSERDA Department of Transportation Buffalo Main Street: Smart Corridor Plan Final Report Prepared for: New York State Energy Research and Development Authority New York, NY Robyn Marquis Project Manager and New York State Department of Transportation Albany, NY Mark Grainer Joseph Buffamonte, Region 5 Project Managers Prepared by: Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus, Inc. & WSP USA Inc. Buffalo, New York NYSERDA Report 20-24 NYSERDA Contract 112009 August 2020 NYSDOT Project No. C-17-55 Notice This report was prepared by Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus, Inc. in coordination with WSP USA Inc., in the course of performing work contracted for and sponsored by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (hereafter “NYSERDA”). The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of NYSERDA or the State of New York, and reference to any specific product, service, process, or method does not constitute an implied or expressed recommendation or endorsement of it. Further, NYSERDA, the State of New York, and the contractor make no warranties or representations, expressed or implied, as to the fitness for particular purpose or merchantability of any product, apparatus, or service, or the usefulness, completeness, or accuracy of any processes, methods, or other information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this report. NYSERDA, the State of New York, and the contractor make no representation that the use of any product, apparatus, process, method, or other information will not infringe privately owned rights and will assume no liability for any loss, injury, or damage resulting from, or occurring in connection with, the use of information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this report. -

Iso/Iec/Ieee 29148:2011(E)

INTERNATIONAL ISO/IEC/ STANDARD IEEE 29148 First edition 2011-12-01 Systems and software engineering — Life cycle processes — Requirements engineering Ingénierie des systèmes et du logiciel — Processus du cycle de vie — Ingénierie des exigences Reference number ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148:2011(E) © ISO/IEC 2011 © IEEE 2011 ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148:2011(E) PDF disclaimer This PDF file may contain embedded typefaces. In accordance with Adobe's licensing policy, this file may be printed or viewed but shall not be edited unless the typefaces which are embedded are licensed to and installed on the computer performing the editing. In downloading this file, parties accept therein the responsibility of not infringing Adobe's licensing policy. The ISO Central Secretariat, the IEC Central Office and IEEE do not accept any liability in this area. Adobe is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Details of the software products used to create this PDF file can be found in the General Info relative to the file; the PDF-creation parameters were optimized for printing. Every care has been taken to ensure that the file is suitable for use by ISO member bodies and IEEE members. In the unlikely event that a problem relating to it is found, please inform the ISO Central Secretariat or IEEE at the address given below. COPYRIGHT PROTECTED DOCUMENT © ISO/IEC 2011 © IEEE 2011 All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without permission in writing from ISO, IEC or IEEE at the respective address below. -

Concept of Operations

MAASTO TPIMS Project CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS July 15, 2016 MAASTO TPIMS Project Concept of Operations Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................................1 1.0 Purpose and Overview .......................................................................................................2 2.0 Scope .................................................................................................................................5 3.0 Referenced Documents......................................................................................................5 4.0 Background ........................................................................................................................8 4.1 National Truck Parking Issues ........................................................................................8 4.1.1 Safety Concerns ......................................................................................................8 4.1.2 Economic Concerns...............................................................................................10 4.2 National Research Programs........................................................................................11 4.3 Current Systems ...........................................................................................................12 5.0 User-Oriented Project Development.................................................................................12 5.1 TPIMS Partnership -

Concept of Operations for C-ITS Core Functions

Research Report AP-R479-15 Concept of Operations for C-ITS Core Functions Concept of Operations for C-ITS Core Functions Prepared by Publisher Freek Faber and David Green Austroads Ltd. Level 9, 287 Elizabeth Street Sydney NSW 2000 Australia Project Manager Phone: +61 2 9264 7088 [email protected] Stuart Ballingall www.austroads.com.au Abstract About Austroads This document defines the core functions of the C-ITS platform Austroads’ purpose is to: including their objectives and capabilities. It identifies user needs • promote improved Australian and New Zealand transport and describes how the system will operate. outcomes • provide expert technical input to national policy The Concept of Operations is intended to be an input to future development on road and road transport issues decision making and system engineering documents, including • promote improved practice and capability by road system requirements and design documentation. agencies • promote consistency in road and road agency operations. Austroads membership comprises the six state and two territory road transport and traffic authorities, the Commonwealth Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, the Australian Local Government Association, and NZ Transport Agency. Austroads is governed by a Board consisting of the chief executive officer (or an alternative senior executive officer) of each of its eleven member organisations: • Roads and Maritime Services New South Wales Keywords • Roads Corporation Victoria Cooperative ITS, C-ITS, Concept of Operations, ConOps, core • Department of Transport and Main Roads Queensland system, core functions. • Main Roads Western Australia ISBN 978-1-925294-13-2 • Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure South Australia Austroads Project No. -

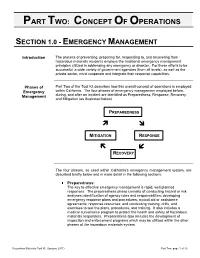

Concept of Operations

PART TWO: CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS SECTION 1.0 - EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT Introduction The process of preventing, preparing for, responding to, and recovering from hazardous materials incidents employs the traditional emergency management principles utilized in addressing any emergency or disaster. For these efforts to be successful, a wide variety of government agencies (from all levels), as well as the private sector, must cooperate and integrate their response capabilities. Phases of Part Two of the Tool Kit describes how this overall concept of operations is employed Emergency within California. The four phases of emergency management employed before, Management during, and after an incident are identified as Preparedness, Response, Recovery, and Mitigation (as illustrated below). PREPAREDNESS MITIGATION RESPONSE RECOVERY The four phases, as used within California's emergency management system, are described briefly below and in more detail in the following sections. Preparedness: The key to effective emergency management is rapid, well planned responses. The preparedness phase consists of conducting hazard or risk analyses; identification of agency roles and responsibilities; developing emergency response plans and procedures; mutual aid or assistance agreements; response resources; and conducting training, drills, and exercises to test the plans, procedures, and training. It also includes a medical surveillance program to protect the health and safety of hazardous materials responders. Preparedness also includes the development of -

AP 210 Domain Specific Entities (Subtypes of Generic Resource Entities) and Rules Are Added to Meet the Domain Requirements

NISTIR 7677 AP210 Edition 2 Concept of Operations Jamie Stori SFM Technology, Inc. Urbana, Illinois Kevin Brady National Institute of Standards and Technology Electronics and Electrical Engineering Laboratory Thomas Thurman Rockwell Collins, Cedar Rapids, Iowa 1 NISTIR 7677 AP210 Edition 2 Concept of Operations Jamie Stori SFM Technology, Inc. Urbana, Illinois Kevin Brady National Institute of Standards and Technology Electronics and Electrical Engineering Laboratory Thomas Thurman Rockwell Collins, Cedar Rapids, Iowa April 2010 U.S. Department of Commerce Gary Locke, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Patrick D. Gallagher, Director 2 AP210 Edition 2 Concept of Operations This document provides information to support organizations wishing to develop data exchange and sharing implementations using AP 210. Contents 1. Background..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Product types that are supported by AP 210 ..................................................................................... 6 3. Life cycle stages that are supported by AP 210 ................................................................................ 7 4. Disciplines that are supported by AP 210 ........................................................................................ 8 5. Product data types that are supported by AP 210 ............................................................................. 9 5.1 Information Rights Data ........................................................................................... -

System Concept of Operations (CONOPS) for the Automated Computer Network Defence (ARMOUR) Technology Demonstration (TD) Contract

System Concept of Operations (CONOPS) for the Automated Computer Network Defence (ARMOUR) Technology Demonstration (TD) Contract Author: D. Tremblay General Dynamics Prepared By: General Dynamics Mission Systems–Canada Land and Joint Solutions 1020–68th Avenue N.E. Calgary, Alberta T2E 8P2 Contractor's Document Number: 740928 Contractor’s date of publication: 21 April 2017 CDRL: SD0049 PWGSC Contract Number: W7717-115274/001/SV Contract Project Manager: Darcy Simmelink Technical Authority: Natalie Nakhla Disclaimer: The scientific or technical validity of this Contract Report is entirely the responsibility of the Contractor and the contents do not necessarily have the approval or endorsement of the Department of National Defence of Canada. Contract Report DRDC-RDDC-2017-C169 July 2017 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2017. © Sa Majesté la Reine (en droit du Canada), telle que représentée par le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2017. 740928F System Concept of Operations (CONOPS) for the Automated Computer Network Defence (ARMOUR) Technology Demonstration ((TD) Contract Contract No. W7714-115274/001/SV CDRL SD009 This document was prepared by General Dynamiccs Mission Systems – Canada under Public Works and Government Service Canada Contract No. W7714- 115274/001/SV. Use and dissemination of the information herein shall be in accordance with the Terms and Conditions Contracct No. W7714-115274/001/SV. © HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF CANADA (2017) Prepared For: Defence Research & Development Caanada (DRDC) - Ottawa 3701 Carling Avenue Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0Z4 Prepared By: General Dynamics Mission Systems – Canada Land and Joint Soluttions 1020-68th Avenue N.E. -

Concept of Operations Versus Operations Concept: How Do You Choose?

PROCEEDINGS OF SPIE SPIEDigitalLibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie Concept of operations versus operations concept: how do you choose? Hill, Alexis, Flagey, Nicolas, Barden, Sam, Erickson, Darren, Sivanandam, Suresh, et al. Alexis Hill, Nicolas Flagey, Sam Barden, Darren Erickson, Suresh Sivanandam, Kei Szeto, "Concept of operations versus operations concept: how do you choose?," Proc. SPIE 11450, Modeling, Systems Engineering, and Project Management for Astronomy IX, 114502U (13 December 2020); doi: 10.1117/12.2563469 Event: SPIE Astronomical Telescopes + Instrumentation, 2020, Online Only Downloaded From: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie on 26 Jan 2021 Terms of Use: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/terms-of-use Concept of Operations versus Operations Concept: How do you choose? Alexis Hill*a,b, Nicolas Flagey b, Sam Barden b, Darren Ericksona, Suresh Sivanandamc,d, Kei Szeto b,a aNational Research Council of Canada, Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics, Victoria, BC, Canada bCFHT Corporation, Corporation, 65-1238 Mamalahoa Hwy, Kamuela, Hawaii 96743, USA cDepartment of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Toronto, 50 St. George St. Toronto, ON, Canada dDunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Toronto, 50 St. George St., Toronto, ON, Canada ABSTRACT Systems engineering as a discipline is relatively new in the ground-based astronomy community and is becoming more common as projects become larger, more complex and more geographically diverse. Space and defense industry projects have been using systems engineering for much longer, however those projects don’t necessarily map well onto ground- based astronomy projects, for various reasons. Fortunately, many of the processes and tools have been documented by INCOSE, NASA, SEBoK and other organizations, however there can be incomplete or conflicting definitions within the process and implementation is not always clear. -

Iso/Iec/Ieee 29148:2011(E)

Important Notice This document is a copyrighted IEEE Standard. IEEE hereby grants permission to the recipient of this document to reproduce this document for purposes of standardization activities. No further reproduction or distribution of this document is permitted without the express written permission of IEEE Standards Activities. Prior to any use of this standard, in part or in whole, by another standards development organization, permission must first be obtained from the IEEE Standards Activities Department ([email protected]). IEEE Standards Activities Department 445 Hoes Lane Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA INTERNATIONAL ISO/IEC/ STANDARD IEEE 29148 First edition 2011-12-01 Systems and software engineering — Life cycle processes — Requirements engineering Ingénierie des systèmes et du logiciel — Processus du cycle de vie — Ingénierie des exigences Reference number ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148:2011(E) © ISO/IEC 2011 © IEEE 2011 ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148:2011(E) PDF disclaimer This PDF file may contain embedded typefaces. In accordance with Adobe's licensing policy, this file may be printed or viewed but shall not be edited unless the typefaces which are embedded are licensed to and installed on the computer performing the editing. In downloading this file, parties accept therein the responsibility of not infringing Adobe's licensing policy. The ISO Central Secretariat, the IEC Central Office and IEEE do not accept any liability in this area. Adobe is a trademark of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Details of the software products used to create this PDF file can be found in the General Info relative to the file; the PDF-creation parameters were optimized for printing. -

Svensk Standard Ss-Iso/Iec/Ieee 12207:2018

SVENSK STANDARD SS-ISO/IEC/IEEE 12207:2018 Fastställd/Approved: 2018-04-12 Publicerad/Published: 2018-04-12 Utgåva/Edition: 1 Språk/Language: engelska/English ICS: 06.030; 35.080 System- och programvarukvalitet – Livscykelprocesser för programvara (ISO / IEC / IEEE 12207:2017, IDT) Systems and software engineering – Software life cycle processes (ISO / IEC / IEEE 12207:2017, IDT) This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-80003485 This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-80003485 Standarder får världen att fungera SIS (Swedish Standards Institute) är en fristående ideell förening med medlemmar från både privat och offentlig sektor. Vi är en del av det europeiska och globala nätverk som utarbetar internationella standarder. Standarder är dokumenterad kunskap utvecklad av framstående aktörer inom industri, näringsliv och samhälle och befrämjar handel över gränser, bidrar till att processer och produkter blir säkrare samt effektiviserar din verksamhet. Delta och påverka Som medlem i SIS har du möjlighet att påverka framtida standarder inom ditt område på nationell, europeisk och global nivå. Du får samtidigt tillgång till tidig information om utvecklingen inom din bransch. Ta del av det färdiga arbetet Vi erbjuder våra kunder allt som rör standarder och deras tillämpning. Hos oss kan du köpa alla publikationer du behöver – allt från enskilda standarder, tekniska rapporter och standard- paket till handböcker och onlinetjänster. Genom vår webbtjänst e-nav får du tillgång till ett lättnavigerat bibliotek där alla standarder som är aktuella för ditt företag finns tillgängliga. Standarder och handböcker är källor till kunskap. -

Computing and Communications Infrastructure for Network-Centric Warfare: Exploiting COTS, Assuring Performance

Submitted to: 2004 Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium The Power of Information Age Concepts and Technologies Topic: C4ISR/C2 Architecture Computing and communications infrastructure for network-centric warfare: Exploiting COTS, assuring performance James P. Richardson, Lee Graba, Mukul Agrawal Honeywell International 3660 Technology Drive Minneapolis, MN 55418 (612) 951-7746 (voice), -7438 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 Abstract In network centric warfare (NCW), the effectiveness of warfighters and their platforms is enhanced by rapid and effective information flow. This requires a robust and flexible computing and communications software infrastructure, and a degree of system integration beyond what has ever been achieved. The design of this infrastructure is a tremendous challenge for a number of reasons. We argue that an appropriately architected software infrastructure can employ COTS software to realize much of the required functionality, while having the necessary degree of performance assurance required for military missions. Perhaps the biggest challenge is system resource management—allocation of computing and communications resources to COTS and custom software alike so that performance requirements can be met. We describe an approach to system resource management appropriate to the NCW environment. 2 1 Introduction Network centric warfare has been defined as: …an information superiority-enabled concept of operations that generates increased combat -

Smart Columbus System Requirements for Connected

1 Smart Columbus 2 System Requirements 3 for Connected Vehicle Environment 4 for the Smart Columbus 5 Demonstration Program 6 www.its.dot.gov/index.htm 7 Draft Report – October 24, 2018 8 9 Source: City of Columbus – November 2015 10 11 Produced by City of Columbus 12 U.S. Department of Transportation 13 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology 14 Notice 15 This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of 16 Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government 17 assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. 18 The U.S. Government is not endorsing any manufacturers, products, or services cited 19 herein and any trade name that may appear in the work has been included only because 20 it is essential to the contents of the work. 21 Acknowledgment of Support 22 This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Transportation 23 under Agreement No. DTFH6116H00013. 24 Disclaimer 25 Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this 26 publication are those of the Author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. 27 Department of Transportation. 28 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Smart Columbus October 24, 2018 Systems Requirements for Connected Vehicle Environment (CVE) for Smart 6. Performing Organization Code Columbus Demonstration Program 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Ryan Bollo, City of Columbus; Dr. Christopher Toth, WSP; Thomas Timcho, WSP, Jessica Baker, HNTB, Robert James, HNTB 9.