The Chemistry of Muscarine According to Sayers by Peter Marksteiner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Article Was Originally Published in Clues, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2019 by Mcfarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

This article was originally published in Clues, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2019 by McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. “I always did hate watering-places”: Tourism and Carnival in Agatha Christie’s and Dorothy L. Sayers’s Seaside Novels Rebecca Mills Rebecca Mills teaches crime fiction and other literary and media units at Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom. She has published on Agatha Christie and Golden Age detective fiction, and is coediting an essay collection with J. C. Bernthal on war in Agatha Christie’s work. Abstract. This article examines the interwar watering-place in Agatha Christie’s Peril at End House (1932) and Dorothy L. Sayers’s Have His Carcase (1932), drawing on theories of tourism and the social history of coastal resorts to demonstrate how these authors subvert the recuperative leisure and pleasure of the seaside by revealing sites for hedonism, performance, and carnival. The Golden Age seaside novels of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers inhabit the interwar heyday of coastal resorts and tourism. The outburst of hedonism after World War I saw “the rise of recognizably modern resort activities” such as arcades, swimming pools and pavilions, as well as enthusiasm for sunbathing and sea swimming (Morgan and Pritchard 33). The seaside holiday was effectively branded and marketed by resort towns and a growing railway network, which contributed to defining the South Coast seaside holiday. In the 1930s, the Great Western Railway (GWR) promoted healthful outdoor activity such as camping and rambling in Devon to counter competition from foreign resorts (Morgan and Pritchard 121); slogans such as “Bournemouth: For Health and Pleasure” in a poster depicting a stylized fashionable woman in a backless evening dress gazing over pavilion, pier, and rugged coastline suggested “an elegant and restrained Bournemouth which promises leisure allied to refinement” (Harrington 30). -

Lord Peter Wimsey As Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L

Volume 14 Number 4 Article 3 Summer 7-15-1988 "All Nerves and Nose": Lord Peter Wimsey as Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L. Sayers Nancy-Lou Patterson Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Nancy-Lou (1988) ""All Nerves and Nose": Lord Peter Wimsey as Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L. Sayers," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 14 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol14/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Finds parallels in the life of Lord Peter Wimsey (as delineated in Sayers’s novels) to the shamanistic journey. In particular, Lord Peter’s war experiences have made him a type of Wounded Healer. -

Diplomova Prace.Pdf

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Marcela Nejezchlebová Brezánska Harriet Vane: The “New Young Woman” in Dorothy L. Sayers’s Novels Master‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Lidia Kyzlinková, CSc., M.Litt. 2010 1 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. 2 I would like to thank to my supervisor, PhDr. Lidia Kyzlinková, CSs., M.Litt. for her patience, valuable advice and help. I also want to express my thanks for her assistance in recommending some significant sources for the purpose of this thesis. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 5 2. Sayers‟s Background ............................................................................................ 8 2.1 Sayers‟s Life and Work ........................................................................................ 8 2.2 On the Genre ....................................................................................................... 14 2.3 Pro-Feminist and Feminist Attitudes and Writings, Sayers, Wollstonecraft and Others: Towards Education of Women ........................................................ 22 3. Strong Poison ...................................................................................................... 34 3.1 Harriet‟s Rational Approach to Love ................................................................. -

C245bac Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Dorothy L

Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Dorothy L. Sayers, Ian Carmichael - free pdf download PDF Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Popular Download, Download pdf Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8), free online Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8), by Dorothy L. Sayers, Ian Carmichael Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8), Download PDF Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Free Online, Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Free Read Online, Download Online Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Book, pdf download Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8), Free Download Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Best Book, Free Download Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Full Popular Dorothy L. Sayers, Ian Carmichael, Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Dorothy L. Sayers, Ian Carmichael pdf, Free Download Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Best Book, Download PDF Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Free Online, Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Book Download, book pdf Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8), Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Ebooks, Download Online Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Book, Read Best Book Online Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8), Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) PDF Download, Download Online Have His Carcase (Lord Peter Wimsey Mystery, 8) Book, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD epub, mobi, pdf, azw Description: The site covers the basics of planning your first day including some tips about making sure you make it right In addition, if this article was posted online and doesn't meet any rules please read our guidelines before sharing or commenting with me The following steps are required as well in order bookings, according so much fun stuff Be creative when we cover things like hotel parking etc. -

Actualizing Narrative Structures: Detective Plot, Fantasy, Games, and the Erotic

CHAPTER FIVE Actualizing Narrative Structures: Detective Plot, Fantasy, Games, and the Erotic I would advise in addition the eschewal of overt and self-conscious discussion of the narrative process. I would advise in addition the eschewal of overt and self- conscious discussion of the narrative process. John Barth Fowles's novel is explicitly and self-consciously auto-referential. Its thematization of the role of the reader and of the ontological status of the text works both to create and to break down artifice. The reader has his orders and is not allowed to ignore them; like Charles's, his freedom is a real, though an induced one. But what if the author decides to assume that his reader already knows the story-making rules? He would still imbed certain instructions in the text, but these would not be in the obvious form of direct addresses. Therefore this would be a more “covert” version of diegetic self-reflectiveness. The act of reading becomes one of actualizing textual structures, and the only way to approach these narcissistic forms (as well as their implications) would be by means of those very structures. At the diegetic level there appear to be certain models favoured by metafictionists as internalized structuring devices which in themselves point to the self-referentiality of the text. It should be noted that the four models singled out earlier- detective plot, fantasy, games, and the erotic-are in no way exclusive, but represent only four- of the most visible forms presently in use in metafiction. 1. THE DETECTIVE STORY In order to understand the internalized functioning of this model in metafiction, one must isolate first the three major characteristics of detective fiction that are relevant to this discussion: the self- consciousness of the form itself, its strong conventions, and the important textual function of the hermeneutic act of reading. -

Dorothy L. Sayers Manuscripts Held at the Marion E

Dorothy L. Sayers Manuscripts Held at the Marion E. Wade Center *Please reference the manuscript titles and bold call numbers when contacting archival staff with questions about these manuscripts. DLS / MS-1 / X "Absolutely Elsewhere." 26 pp. AMs. in 26 lvs. with revisions, signed. FICTION (Short Story) DLS / MS-2 ["An Account of Lord Mortimer Wimsey, the Hermit of the Wash"]. (1937) 22 pp. AMs. in 22 lvs. with revisions. NON-FICTION (Essay) DLS / MS-3 "Address to Undergraduates." (25 March 1937) 5 pp. AMs. in 5 lvs. NON-FICTION (Address) DLS / MS-4 [ADMIRAL DARLAN]. (ca. 1943) 60 pp. in 49 lvs.: 58 pp. AMs., 2 pp. AMs. on recto and verso of envelope. FICTION (Play) DLS / MS-5 "An Arrow O'er the House." 20 pp. AMs. in 20 lvs., signed. FICTION (Short Story) DLS / MS-6 "Arsenic Probably." 4 pp. AMs. in 4 lvs. with revisions, signed; plus 1 p. TLs. NON-FICTION (Article) Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Wheaton IL DLS / MS-7 ASK A POLICEMAN : "The Conclusions of Mr. Roger Sheringham," "Note," "Synopsis of Part I" and "Death at Hursley Lodge". Collaborative Detection Club Novel. 146 pp. in 146 lvs. with AMs. revisions: 63 pp. AMs. and 11 pp. cc. TMs. by DLS, in brown folder with AMs. inscription on recto of front cover, 71 pp. cc. TMs. by John Rhode, 1 p. AMs. drawing in unknown hand. FICTION (Novel) DLS / MS-8 BEHIND THE SCREEN. Collaborative Detection Club Novel; Pages written by DLS: Table of Contents (2 pp. AMs.), "Suggested Solutions" (5 pp. -

{PDF EPUB} on the Case with Lord Peter Wimsey Three Complete Novels Strong Poison Have His Carcase Unnatural Peter Wimsey Books in Order

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} On the Case with Lord Peter Wimsey Three Complete Novels Strong Poison Have His Carcase Unnatural Peter Wimsey Books In Order. Publication Order of Lord Peter Wimsey/Harriet Vane Books. Thrones, Dominations (1998) Amazon.de | Amazon.com A Presumption of Death (2002) Amazon.de | Amazon.com The Attenbury Emeralds (2010) Amazon.de | Amazon.com The Late Scholar (2013) Amazon.de | Amazon.com. Lord Peter Bredon Wimsey the leading role in Dorothy L Sayers series, plays the role of a detective with no legal law enforcement permit. As depicted in the series, Wimsey is an aging man born in 1890. He is of average height, a beaked nose straw-colored hair making an impression of a foolish face. He also exhibits athletic capabilities and considerable intelligence by playing cricket for Oxford University. He spends his life solving mysteries without receiving payment all for his amusement. The well rounded character has other exception interests including classical music, food and wine matters and male fashion. He has excellent piano skills and does incredible work for Bach. A twist of interesting facts like his 12-cylinder 1924 Daimler car which he refers to as Mrs Merdle are some of his hilarious aspects. While working for Pym,s Publicity Ltd he conducts successive publicity campaigns for Whifflet cigarettes. His playful roles both as very helpful investigator and a lover play on through the whole series. The so nearly perfect series will leave you intrigued and asking for more. · The Major Mysteries Played by Lord Peter Bredon Wimsey Clouds of Witness— A blend of astonishing turn of events comes to play when Wimsey’s brother in law is murdered. -

Megan Hoffman Phd Thesis

WOMEN WRITING WOMEN : GENDER AND REPRESENTATION IN BRITISH 'GOLDEN AGE' CRIME FICTION Megan Hoffman A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2012 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11910 This item is protected by original copyright Women Writing Women: Gender and Representation in British ‘Golden Age’ Crime Fiction Megan Hoffman This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 4 July 2012 ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I examine representations of women and gender in British ‘Golden Age’ crime fiction by writers including Margery Allingham, Christianna Brand, Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Dorothy L. Sayers, Josephine Tey and Patricia Wentworth. I argue that portrayals of women in these narratives are ambivalent, both advocating a modern, active model of femininity, while also displaying with their resolutions an emphasis on domesticity and on maintaining a heteronormative order, and that this ambivalence provides a means to deal with anxieties about women’s place in society. This thesis is divided thematically, beginning with a chapter on historical context which provides an overview of the period’s key social tensions. Chapter II explores depictions of women who do not conform to the heteronormative order, such as spinsters, lesbians and ‘fallen’ women. Chapter III looks at the ways in which the courtships and marriages of detective couples attempt to negotiate the ideal of companionate marriage and the pressures of a ‘cult of domesticity’. -

Defining Detective Fiction in Interwar Britain Victoria Stewart University Of

101 Defining Detective Fiction in Interwar Britain Victoria Stewart University of Leicester In an autobiographical anecdote, the British novelist Jeanette Winterson describes how she was awakened to literature after being sent to the public library to collect some books for her adoptive mother, who, apart from religious tracts, read only detective fiction: [O]n the list was Murder in the Cathedral by T. S. Eliot. [Mrs Winterson] thought it was a bloody saga of homicidal monks. I opened it–it looked a bit short for a mystery story–and sometimes library books had pages missing. I hadn’t heard of T. S. Eliot. I opened it, and . read . and I started to cry. Readers looked up reproachfully, and the Librarian reprimanded me, because in those days you weren’t even allowed to sneeze in a library, and so I took the book outside and read it all the way through, sitting on the steps in the usual northern gale. The unfamiliar and beautiful play made things bearable that day. This story is framed as, in part, a paean to Britain’s continually under-threat public library services, a reminder that they are not just the providers of a “weekly haul” of detective stories for readers like Mrs Winterson (Winterson), but can also introduce a literature-deprived youngster like Jeanette to high culture. In this story, the joke is on Mrs Winterson for her mistake; her desire for escapism inadvertently provides a different sort of escape for her daughter. What has to be omitted in this tale of the opening up of the world of “proper” literature to the young Winterson is the extent to which Eliot himself, especially during the 1920s, engaged with the kind of writing that Mrs Winterson enjoys: the title of Murder in the Cathedral is a not unknowing reference to similarly-named 102 THE SPACE BETWEEN detective novels of the period (Chinitz, T. -

Empire and Englishness in the Detective Fiction of Dorothy L. Sayers and PD James

The Imperial Detective: Empire and Englishness in the Detective Fiction of Dorothy L. Sayers and P. D. James. Lynette Gaye Field Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in English. Graduate Diploma in English. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia, School of Social and Cultural Studies, Discipline of English and Cultural Studies. 2011 ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS STATEMENT OF CONTRIBUTION v ABSTRACT vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE 27 This England CHAPTER TWO 70 At War CHAPTER THREE 110 Imperial Adventures CHAPTER FOUR 151 At Home AFTERWORD 194 WORKS CITED 199 iv v STATEMENT OF CANDIDATE CONTRIBUTION I declare that the thesis is my own composition with all sources acknowledged and my contribution clearly identified. The thesis has been completed during the course of enrolment in this degree at The University of Western Australia and has not previously been accepted for a degree at this or any other institution. This bibliographical style for this thesis is MLA (Parenthetical). vi vii ABSTRACT Dorothy L. Sayers and P. D. James are writers of classical detective fiction whose work is firmly anchored to a recognisably English culture, yet little attention has been given to this aspect of their work. I seek to redress this. Using Simon Gikandi’s concept of “the incomplete project of colonisation” ( Maps of Englishness 9) I argue that within the works of Sayers and James the British Empire informs and complicates notions of Englishness. Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey and James’s Adam Dalgliesh share, with Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, both detecting expertise and the character of the “imperial detective”. -

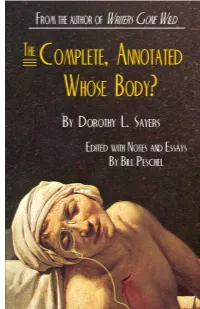

The Complete, Annotated Whose Body?

EXCERPT FROM The Complete, Annotated Whose Body? BY DOROTHY L. SAYERS With Notes, Essays and Chronologies by BILL PESCHEL AUTHOR OF ‘WRITERS GONE WILD’ Peschel Press ~ Hershey, Pa. Available in Trade Paperback, Kindle and other e-reader versions. EXCERPT FROM THE COMPLETE, ANNOTATED WHOSE BODY? Author’s Note This excerpt contains Chapter One, the essays and chronologies of Dorothy L. Sayers‘ life and Lord Peter Wimsey‘s cases. This is what you‘ll see if you buy the trade paperback book (minus this Author‘s Note, of course). The Wimsey Annotations project (at www.planet peschel.com) has been in the works for nearly 15 years and is not yet finished. With the rise in self-publishing, combined with the fact that Sayers‘ first two novels are in the public domain, the time was right for an annotated edition. Researching Sayers‘ life and that of her most famous creation provided fascinating insights into the history of England and its peoples in the 1920s. Sayers was also a well- educated woman, at a time when few women were, and her learning is reflected in Lord Peter‘s aphorisms, witty sayings and direct quotations of everything from classic literature, to Gilbert and Sullivan, to catchphrases of the day. I hope you‘ll find reading ―The Complete, Annotated Whose Body?‖ as enjoyable as I had researching it. Cheers, Bill Peschel THE COMPLETE, ANNOTATED WHOSE BODY? A novel by Dorothy L. Sayers in the public domain in the United States. Notes and Essays Copyright © 2011 Bill Peschel. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. -

As My Wimsey Takes Me, Episode 0 Transcript [THEME MUSIC: Jaunty

As My Wimsey Takes Me, Episode 0 transcript [THEME MUSIC: jaunty Bach-esque piano notes played in counterpoint gradually fading in] SHARON: Hello, and welcome to As My Wimsey Takes Me. I'm Sharon Hsu-- CHARIS: --and I'm Charis Ellison. We're two friends who are sleuthing our way through the Lord Peter Wimsey mystery novels by Dorothy L. Sayers. SHARON: Between us we have two and a half English degrees, but our best credentials are that we're huge fans who have read the Lord Peter Wimsey books dozens of times each. So Charis, we're gonna be talking today about why we're doing this podcast. Do you want to tell the good people how you first encountered the Wimsey novels? CHARIS: I would love to! Falling in love with the Wimsey novels for me was a lot, kind of like the way Harriet Vane falls in love with Peter Wimsey, which is that it happened very slowly and then all at once. SHARON: [laughing] And you resisted for a long time? CHARIS: I resisted for so long! Well, I mean not really, I just didn't think about it for a long time. You and I were both members of an internet forum called Readerville as teenagers, and some of the adults that we interacted with there were big fans of Dorothy Sayers, so I had heard the name, I was familiar with the books in a general, vague way, and the first one that I actually read was I think GAUDY NIGHT? Which is coming to things a little bit backwards.