Resolving Holiday Pay Disputes in Labor Arbitration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOLIDAY PAY INTRODUCTION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction EUROPEAN LAW NATIONAL LAW the Right for Workers to Take Paid Annual Leave Is Well Established Across Europe

BREDIN PRAT HENGELER MUELLER NEWS SLAUGHTER AND MAY NO 12/ JUNE 2015 QUICK LINKS HOLIDAY PAY INTRODUCTION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction EUROPEAN LAW NATIONAL LAW The right for workers to take paid annual leave is well established across Europe. However, the way CONCLUSION in which holiday pay is calculated was for many years largely unregulated at a European level, with each Member State left to formulate its own rules. In recent years a spate of European cases have begun to lay down some core principles for the calculation of holiday pay. Despite these cases, many of the practical details for calculating holiday pay are still left to Member States, and this creates scope for some interesting variations. This briefing examines the European rules on holiday pay, and the way in which those principles are implemented in France, Germany and the UK. We have set out below an executive summary of the key differences in each jurisdiction, which is followed by more detail on the position under European law and in each of the three countries. Executive summary • Calculating holiday pay: In the UK, the process varies depending on the working pattern, but essentially workers are entitled to a week’s pay for each week of holiday, in some cases using a 12 week reference period. In Germany, holiday pay is based on a worker’s daily or hourly rate, calculated over a 13 week reference period. In France there is a dual calculation method; workers receive the higher of (i) what they would have earned if they had worked during their holiday; or (ii) an amount calculated over a one year reference period. -

Oregon Statewide Payroll Application ‐ Paystub Pay and Leave Codes

Oregon Statewide Payroll Application ‐ Paystub Pay and Leave Codes PAYSTUB PAY AND LEAVE CODES Pay Type Code Paystub Description Detail Description ABL OSPOA BUSINESS Leave used when conducting OSPOA union business by authorized individuals. Leave must be donated from employees within the bargaining unit. A donation/use maximum is established by contract. AD ADMIN LV Paid leave time granted to compensate for work performed outside normal work hours by Judicial Department employees who are ineligible for overtime. (Agency Policy) ALC ASST LGL DIF 5% Differential for Assistant Legal Counsel at Judicial Department. (PPDB code) ANA ALLW N/A PLN Code used to record taxable cash value of non-cash clothing allowance or other employee fringe benefit. (P050) ANC NRS CRED Nurses credentialing per CBA ASA APPELATE STF Judicial Department Appellate Judge differential. (PPDB code) AST ADDL STRAIGHTTIME Additional straight time hours worked within same period that employee recorded sick, holiday, or other regular paid leave hours. Refer to Statewide Policy or Collective Bargaining Agreement. Hours not used in leave and benefit calculations. AT AWARD TM TKN Paid leave for Judicial Department and Public Defense Service employees as years of service award. (Agency Policy) AW ASSUMED WAGES-UNPD Code used to record and track hours of volunteer non-employee workers. Does not VOL HR generate pay. (P050) BAV BP/AWRD VALU Code used to record the taxable cash value of a non-cash award or bonus granted through an agency recognition program. Not PERS subject. (P050 code) BBW BRDG/BM/WELDR Certified Bridge/Boom/Welder differential (PPDB code) BCD BRD CERT DIFF Board Certification Differential for Nurse Practitioners at the Oregon State Hospital of five percent (5%) for all Nurse Practitioners who hold a Board certification related to their assignment. -

FULL BENEFITS (PDF, 250K)

Employee Benefits Contents 125 PREMIUM ONLY PLANS 4 MEDICAL & PRESCRIPTION INSURANCE 4 TELEMEDICINE 7 DENTAL INSURANCE 9 HEALTHCARE FLEXIBLE SPENDING ACCOUNT 10 QUALIFIED EXPENSES 11 DEPENDENT CARE FLEXIBLE SPENDING ACCOUNT 12 AFLAC 13 401(k) SAVINGS PLAN 14 HOLIDAYS 15 EARNED TIME OFF 16 SERVICE AWARDS 17 EXTENDED SICK TIME 18 RHODE ISLAND PAID SICK & SAFE LEAVE 18 OVERTIME 19 TUITION REIMBURSEMENT 20 FREE ASL CLASSES 20 DIRECT SUPPORT PROFESSIONAL MENTOR PROGRAM 21 REFERRAL BONUS PROGRAMS 22 LEAVE OF ABSENCE 23 WORKERS COMPENSATION 23 BEREAVEMENT 23 JURY DUTY 24 DIRECT DEPOSIT OF PAYROLL 24 ANNUAL BIG BASH 24 VERIZON WIRELESS DISCOUNT 25 EMAIL & WEBSITE ACCESS 25 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION 25 CLOSING REMARKS 25 Page | 2 Employee Benefits At Perspectives Corporation we recognize our ultimate success depends on our talented and dedicated workforce. We offer a variety of employment opportunities, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. We pride ourselves on maximizing the talents of our employees so that the services we provide to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are the best they can be. We understand the contribution each employee makes to our accomplishments and so our goal is to provide a comprehensive program of competitive benefits to attract and retain the best employees available. Through our benefits programs we strive to support the needs of our employees and their dependents by providing a benefit package that is easy to understand, easy to access and affordable for all our employees. This brochure will help you choose the type of plan and level of coverage that is right for you. -

Working in B.C

WORKING IN B.C. The law in B.C. sets standards for payment, com- MINIMUM DAILY PAY pensation and working conditions in most work- An employee who reports for work must be paid places. For more information, please contact the fort a least two hours, even if they work less than Employment Standards Branch: two. hours If the employee is scheduled for more Toll free: 1-833-236-3700 thant eigh hours, they must be paid for at least four gov.bc.ca/EmploymentStandards hours. If work stops for a reason beyond the employer’s MINIMUM WAGE control, the employee must be paid their minimum Employees must be paid at least minimum wage dailyy pa or the actual time worked, whichever is regardless of: longer. • How they are paid – hourly, salary, commission or An employee is only paid for time actually worked if: other incentive basis • They are unfit to work • Their status – full-time, part-time, temporary or permanent • They do not meet WorkSafeBC health and safety regulations The minimum wage in B.C. is as follows: • June 1, 2018 - $12.65 per hour MEAL BREAKS • June 1, 2019 - $13.85 per hour Ae 30-minut unpaid meal break must be provided • June 1, 2020 - $14.60 per hour when an employee works more than five hours in a • June 1, 2021 - $15.20 per hour row. Employers are not required to provide coffee Liquor servers must be paid at least the liquor serv- breaks. er minimum wage: An employee must be paid for the meal break if • June 1, 2018 - $11.40 per hour they’re required to work (or be available to work) • June 1, 2019 - $12.70 per hour during their meal break. -

Collective Bargaining Agreement

COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT BETWEEN CONDOMINIUM COOPERATIVE EMPLOYERS COUNCIL OF SAN FRANCISCO AND SERVICE EMPLOYEES INTERNATIONAL UNION LOCAL 1877 Effective October 1, 2009 – September 30, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Section 0 GENERAL INFORMATION ……………………………………. 1 0.1 Duration of Contract 0.2 Parties to the Agreement 0.3 Intent Section 1 RECOGNITION ……………………………………………………….. 2 1.1 Bargaining Representative 1.2 Strikes and Work Stoppages 1.3 Discrimination 1.4 Contractors and Subcontractors Section 2 UNION MEMBERSHIP ………………………………………………. 3 2.1 Membership as a Condition of Employment 2.2 Discharge for Failure to Join the Union 2.3 Recognition of Shop Stewards and Regional Shop Stewards 2.4 Visitation by Union Representatives 2.5 Bulletin Board 2.6 Dues Collection 2.7 Dues Check Off Form 2.8 Hold Harmless Section 3 EMPLOYERS COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP …………………………. 5 3.1 Employers Council Membership Section 4 HIRING ………………………………………………………………… 5 4.1 Filling of Vacancies and New Positions 4.2 Probation Period for New Employees 4.3 Employer Sole Judge of Qualifications Section 5 SENIORITY ……………………………………………………………. 6 A. SENIORITY DEFINED…………………………………………………………. 6 5.1 Definition B. AN EMPLOYEE SHALL CONTINUE TO ACCRUE SENIORITY DURING .. 6 5.2 Periods of Absence for Worker’s Compensation 5.3 Reinstatement after Termination 5.4 Other Authorized Reasons C. LAYOFF AND RECALL……………………………………………………….. 7 5.5 Layoffs D. NOTICE OF LAYOFF………………………………………………………….. 7 5.6 Notice of Requirement and Pay in the Event of Layoff E. RECALL………………………………………………………………………… 7 5.7 Notice of Requirement for Recall F. CONSIDERATIONS FOR FILLING VACANT POSITIONS…………………. 7 5.8 Considerations – Regular Employees 5.9 Bumping 5.10 Short-term Vacancies G. TRANSFERS……………………………………………………………………. -

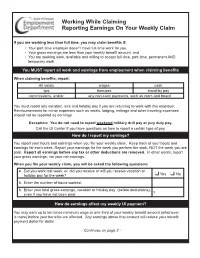

Working While Claiming Reporting Earnings on Your Weekly Claim

Working While Claiming Reporting Earnings On Your Weekly Claim If you are working less than full time, you may claim benefits if: • Your part-time employer doesn’t have full-time work for you, • Your gross earnings are less than your weekly benefit amount, and • You are seeking work, available and willing to accept full-time, part-time, permanent AND temporary work. You MUST report all work and earnings from employment when claiming benefits When claiming benefits, report: All salary wages cash tips bonuses stand-by pay commissions, and/or any non-cash payments, such as room and board You must report any vacation, sick and holiday pay if you are returning to work with this employer. Reimbursements for minor expenses such as meals, lodging, mileage and other traveling expenses should not be reported as earnings. Exception: You do not need to report weekend military drill pay or jury duty pay. Call the UI Center if you have questions on how to report a certain type of pay. How do I report my earnings? You report your hours and earnings when you file your weekly claim. Keep track of your hours and earnings for each week. Report your earnings for the week you perform the work, NOT the week you are paid. Report all earnings before any tax or other deductions are removed. In other words, report your gross earnings, not your net earnings. When you file your weekly claim, you will be asked the following questions: 4. Did you work last week, or, did you receive or will you receive vacation or q q holiday pay for the week? Yes No 5. -

Holiday Benefit Revised

5.12 Holidays All regular full-time and part-time employees are eligible for holiday benefit for the following holidays: 1st of January - New Year’s Day Third Monday in January – Martin Luther King Jr. Day Third Monday in February – Presidents' Day Last Monday in May – Memorial Day 4th of July – Independence Day First Monday in September – Labor Day Second Monday in October – Columbus Day 11th day of November – Veterans' Day Fourth Thursday in November – Thanksgiving Day Friday after Thanksgiving 25th of December – Christmas * One Floating Holiday *Floating holiday shall be designated by the City Manager and announced prior to January 1. When one of the foregoing regular holidays falls on a Saturday, the preceding Friday shall be declared the holiday. When one of the foregoing regular holidays falls on a Sunday, the following Monday shall be declared the holiday. A. Pay for Holidays Not Worked Full-time employees will receive holiday benefit equivalent to their basic hourly rate times their normal hours worked in a day. Normal hours worked in a day is calculated as their FLSA work week schedule (not to exceed ten (10) hours fire, rescue and police officers on 28 day work cycle, eight (8) hours all others) provided that: 1. The employee worked his or her complete scheduled workday before and after the holiday, unless the employee was on an approved paid leave. 2. Employees on a 7-day, 40-hour work week schedule who are working an alternate work schedule (i.e. 4-day, 10-hour work days), the supervisor will have the option of reverting those employees back to a 5-day, 8-hour work week during the week in which the holiday falls or approving annual leave in order for the employee to be paid for a full 40- hour week. -

Collective Bargaining Agreement 1 October 2017 - 30 September 2020

K9866 Collective Bargaining Agreement 1 October 2017 - 30 September 2020 Alpha-Omega Change Engineering, Inc. (AOCE) & Syracuse Aircrew Trainer Employee Association (SATEA) MQ-9 Formal Training Unit Hancock Air National Guard Base Syracuse, New York Version 20170808V4 Table of Contents AGREEMENT .................................................................................................................................5 PREAMBLE ....................................................................................................................................5 NON-DISCRIMINATION ..............................................................................................................5 ARTICLE 1 (MANAGEMENT RIGHTS) ......................................................................................5 Section 1 - Responsibilities of Company .................................................................................... 5 Section 2 - Waiver of Rights ....................................................................................................... 6 ARTICLE 2 (ASSOCIATION RIGHTS) ........................................................................................6 Section 1 - Exclusive Bargaining Agent ..................................................................................... 6 Section 2 - Association Business and Elections ......................................................................... 6 Section 3 - Association President (Union Steward) ................................................................... -

Employee? Contractor / Self-Employed Person?

Employee? Contractor / Self-employed Person? To avoid misunderstanding or dispute, the relevant persons should understand clearly their mode of cooperation according to their intention and clarify their identities, whether they are engaged as an employee or a contractor/self-employed person, before entering into a contract. This can safeguard mutual rights and benefits. Distinguishing an “employee” from a “contractor or self- employed person” There is no one single conclusive test to distinguish an “employee” from a “contractor or self-employed person”. In differentiating these two identities, all relevant factors of the case should be taken into account. Moreover, there is no hard and fast rule as to how important a particular factor should be. The common important factors include: • control over work procedures, working time and method • ownership and provision of work equipment, tools and materials • whether the person is carrying on business on his own account with investment and management responsibilities • whether the person is properly regarded as part of the employer’s organisation • whether the person is free to hire helpers to assist in the work • bearing of financial risk over business (e.g. any prospect of profit or risk of loss) • responsibilities in insurance and tax • traditional structure and practices of the trade or profession concerned • other factors that the court considers as relevant Since the actual circumstances in each case are different, the final interpretation will rest with the court in case of a dispute. Employees should note An employee should identify who his employer is before entering into an employment contract. If necessary, before the commencement of employment, the employee may make a written request to the employer for written information on conditions of employment in accordance with the Employment Ordinance (EO). -

Holidays and Weekends Are Not Counted As Working Days

20. Does the Department have to take my claim? 1. What is the minimum wage in Alaska? No. The Department can refuse to accept a claim for a Department of Labor and $10.34 per hour, calculated by multiplying all hours variety of reasons such as: it is not a valid or enforceable worked in the pay period by $10.34. This is the least claim; your employer has filed for bankruptcy protection; Workforce Development amount that can be paid to an employee as wages. you have waited too long to file or your claim exceeds an Wage and Hour Administration 2. Does my employer have to pay me more for allowable amount. overtime work? 21. How long does it take to get my money? Yes, but there are a few exceptions. If you work more The time it takes to collect the money from your employer Employees’ Frequently Asked Questions than 8 hours in a single day and/or more than 40 hours can range from several days to a year or more. Many in a single week, you must be paid time-and-one-half (1.5 things can speed up or slow down the payment of a claim. times) your hourly or regular wage for those extra hours If your records are complete and your employer is that you worked. Contact the Wage and Hour cooperative, the process is faster. However, if your Administration office (907) 269-4900 if you have records are poor or your employer is uncooperative, it may questions. take longer. 3. If I am not paid by the hour, do I still need to receive minimum wage and overtime? 22. -

ACA – Guide to Holidays and Holiday Pay 2015

Holidays and holiday pay This leaflet contains helpful information about holiday entitlement, but it does NOT yet contain information about overtime and holiday pay following the Employment Appeal Tribunal Ruling in Bear Scotland Ltd v Fulton (and other joined cases) on 4 November 2014. For more up-to-date information on this area, go to www.acas.org.uk/holidays We inform, advise, train and work with you Every year Acas helps employers and employees from thousands of workplaces. That means we keep right up-to-date with today’s employment relations issues – such as discipline and grievance handling, preventing discrimination and communicating effectively in workplaces. Make the most of our practical experience for your organisation – find out what we can do for you. We inform We answer your questions, give you the facts you need and talk through your options. You can then make informed decisions. Contact us to keep on top of what employment rights legislation means in practice – before it gets on top of you. Call our helpline 0300 123 1100 for free confidential advice (open 8am-8pm, Monday to Friday and 9am-1pm Saturday) or visit our website www.acas.org.uk. We advise and guide We give you practical know-how on setting up and keeping good relations in your organisation. Download one of our helpful publications from our website or call our Customer Services Team on 0300 123 1150 and ask to be put you in touch with your local Acas adviser. We train From a two-hour session on the key points of new legislation or employing people to courses specially designed for people in your organisation, we offer training to suit you. -

City of Gainesville Policy for Flexible Work Arrangements

City of Gainesville Policy for Flexible Work Arrangements Overview and Statement of Policy The City of Gainesville supports flexible work arrangements and allows Departments to implement these arrangements, where appropriate, for eligible employees. Flexible work arrangements may be implemented when they benefit the City of Gainesville in one or more of the following ways. City of Gainesville Citizens -To provide Citizens with an even higher level of service with no delays at the beginning of the business day and continue this level of service until the close of the day. City of Gainesville as an Employer – To improve recruitment and retention of high quality employees, to decrease employee vacancy rates and to provide a no-cost enhancement to the City’s work environment City of Gainesville Employees – To improve job satisfaction, employee morale, effectiveness and productivity; promotes employee health, wellness and reduces absenteeism by helping employees face the demands of juggling work, family and life related issues. Reduce employee’s time of commute, cost of fuel and vehicle maintenance. Sustainability – To position the City as a leader for solutions to reduce traffic congestion and improve air quality and will maximize the utilization of City facilities and resources. The City of Gainesville Offices will be open from 8:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. Monday through Friday unless otherwise determined by the City Manager. Flexible work arrangements shall not result in delayed open or early closing of any offices. Flexible work arrangements shall not diminish the ability of the City to meet all operational requirements, service to the citizens, or the ability to assign responsibility and accountability to individual employees for the provision of services and performance of their duties.