Harry Gullett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GP Text Paste Up.3

FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan Daniel Oakman Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/facing_asia _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Author: Oakman, Daniel. Title: Facing Asia : a history of the Colombo Plan / Daniel Oakman. ISBN: 9781921666926 (pbk.) 9781921666933 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Economic assistance--Southeast Asia--History. Economic assistance--Political aspects--Southeast Asia. Economic assistance--Social aspects--Southeast Asia. Dewey Number: 338.910959 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Emily Brissenden Cover: Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) was commissioned to produce this bookplate for pasting in the front of books donated under the Colombo Plan. Sir Lionel Lindsay, Bookplate from the Australian people under the Colombo Plan, nla.pic-an11035313, National Library of Australia Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press First edition © 2004 Pandanus Books For Robyn and Colin Acknowledgements Thank you: family, friends and colleagues. I undertook much of the work towards this book as a Visiting Fellow with the Division of Pacific and Asian History in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University. There I benefited from the support of the Division and, in particular, Hank Nelson and Donald Denoon. -

General Sir William Birdwood and the AIF,L914-1918

A study in the limitations of command: General Sir William Birdwood and the A.I.F.,l914-1918 Prepared and submitted by JOHN DERMOT MILLAR for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales 31 January 1993 I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of advanced learning, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. John Dermot Millar 31 January 1993 ABSTRACT Military command is the single most important factor in the conduct of warfare. To understand war and military success and failure, historians need to explore command structures and the relationships between commanders. In World War I, a new level of higher command had emerged: the corps commander. Between 1914 and 1918, the role of corps commanders and the demands placed upon them constantly changed as experience brought illumination and insight. Yet the men who occupied these positions were sometimes unable to cope with the changing circumstances and the many significant limitations which were imposed upon them. Of the World War I corps commanders, William Bird wood was one of the longest serving. From the time of his appointment in December 1914 until May 1918, Bird wood acquired an experience of corps command which was perhaps more diverse than his contemporaries during this time. -

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD [1882 – 1976] Major General Cannan is distinguished by his service in the Militia, as a senior officer in World War 1 and as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General in World War 2. Major General James Harold Cannan, CB, CMG, DSO, VD (29 August 1882 – 23 May 1976) was a Queenslander by birth and a long-term member of the United Service Club. He rose to brigadier general in the Great War and served as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General during the Second World War after which it was said that his contribution to the defence of Australia was immense; his responsibility for supply, transport and works, a giant-sized burden; his acknowledgement—nil. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes. The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. File: HIG/Biographies/Cannan Page 1 Cannan was appointed Commanding Officer of the 15th Battalion in 1914 and landed with it at ANZAC Cove on the evening of 25 April 1915. The 15th Infantry Battalion later defended Quinn's Post, one of the most exposed parts of the Anzac perimeter, with Cannan as post commander. On the Western Front, Cannan was CO of 15th Battalion at the Battle of Pozières and Battle of Mouquet Farm. He later commanded 11th Brigade at the Battle of Messines and the Battle of Broodseinde in 1917, and the Battle of Hamel and during the Hundred Days Offensive in 1918. -

February 2017

MONUMENTALLY SPEAKING National Boer War Memorial Association Newsletter for NSW, SA, WA and ACT Artist’s impression NUMBER 30 – FEBRUARY 2017 NATIONAL BOER WAR MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION National Patron: Chief of the Defence Force, Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin AC NSW Committee of NBWMA Inc – Chairman: David Deasey NSW Chairman’s Message involvement that has led to the Memorial Welcome to 2017. We stand at the brink project. We also take a look at the full of our most exciting period of time as design and show some of the technical we head toward the dedication of the intricacies behind the sculptures. Finally memorial, 31 May 2017 at 11am. All of our we have some fascinating stories of supporters and interested members of soldiers and equipment from the war the public are invited to attend this great This has been a great endeavour which occasion. The Organising Committee has spanned 15 years at this point. We hopes to have TV screens in place so that have set the target of funds to be raised all attendees can see where ever they are in this financial year at $100.000. As at placed. Seating will be limited compared December 2016 approximately $35.000 to the numbers likely to attend and had been raised, (over $20.000 from NSW) formal invitations for this seating will be leaving $65.000 still short of the target. issued shortly. Please don’t let that stop This issue will be just about our last you from coming, everyone is welcome. chance of getting those funds in. So Inside this issue we look at the please – if you are thinking of donating – circumstances behind Australia’s Boer War please do it now. -

“Come on Lads”

“COME ON LADS” ON “COME “COME ON LADS” Old Wesley Collegians and the Gallipoli Campaign Philip J Powell Philip J Powell FOREWORD Congratulations, Philip Powell, for producing this short history. It brings to life the experiences of many Old Boys who died at Gallipoli and some who survived, only to be fatally wounded in the trenches or no-man’s land of the western front. Wesley annually honoured these names, even after the Second World War was over. The silence in Adamson Hall as name after name was read aloud, almost like a slow drum beat, is still in the mind, some seventy or more years later. The messages written by these young men, or about them, are evocative. Even the more humdrum and everyday letters capture, above the noise and tension, the courage. It is as if the soldiers, though dead, are alive. Geoffrey Blainey AC (OW1947) Front cover image: Anzac Cove - 1915 Australian War Memorial P10505.001 First published March 2015. This electronic edition updated February 2017. Copyright by Philip J Powell and Wesley College © ISBN: 978-0-646-93777-9 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Map of Gallipoli battlefields ........................................................ 4 The Real Anzacs .......................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. The Landing ............................................................... 6 Chapter 2. Helles and the Second Battle of Krithia ..................... 14 Chapter 3. Stalemate #1 .............................................................. -

The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence 1860-1941

The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence 1860-1941 Andrew Kilsby A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences February 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the rifle club movement and its relationship with Australian defence to 1941. It looks at the origins and evolution of the rifle clubs and associations within the context of defence developments. It analyses their leadership, structure, levels of Government and Defence support, motivations and activities, focusing on the peak bodies. The primary question addressed is: why the rifle club movement, despite its strong association with military rifle shooting, failed to realise its potential as an active military reserve, leading it to be by-passed by the military as an effective force in two world wars? In the 19th century, what became known as the rifle club movement evolved alongside defence developments in the Australian colonies. Rifle associations were formed to support the Volunteers and later Militia forces, with the first ‘national’ rifle association formed in 1888. Defence authorities came to see rifle clubs, especially the popular civilian rifle clubs, as a cheap defence asset, and demanded more control in return for ammunition grants, free rail travel and use of rifle ranges. At the same time, civilian rifle clubs grew in influence within their associations and their members resisted military control. An essential contradiction developed. The military wanted rifle clubs to conduct shooting ‘under service conditions’, which included drill; the rifle clubs preferred their traditional target shooting for money prizes. -

Magazine of the Families and Friends of the First AIF Inc

DIGGER “Dedicated to Digger Heritage” Above: The band of the 1st Australian Light Horse Regiment, taken just before embarkation in 1914. Those men marked with an ‘X’ were killed and those marked ‘O’ were wounded in the war. Photo courtesy of Roy Greatorex, the son of Trooper James Greatorex (later lieutenant, 1st LH Bde MG Squadron), second from right, back row. September 2018 No. 64 Magazine of the Families and Friends of the First AIF Inc Edited by Graeme Hosken ISSN 1834-8963 Families and Friends of the First AIF Inc Patron-in-Chief: His Excellency General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK MC (Retd) Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Founder and Patron-in-Memoriam: John Laffin Patrons-in-Memoriam: General Sir John Monash GCMG KCB VD and General Sir Harry Chauvel CGMG KCB President: Jim Munro ABN 67 473 829 552 Secretary: Graeme Hosken Trench talk Graeme Hosken. This issue A touching part of the FFFAIF tours of the Western Front is when Matt Smith leads a visit to High Tree Cemetery at Montbrehain, where some of the Diggers killed in the last battle fought by the AIF in the war are buried. In this issue, Evan Evans tells the story of this last action and considers whether it was necessary for the exhausted men of the AIF to take part. Andrew Pittaway describes how three soldiers had their burial places identified in Birr Cross Roads Cemetery, while Greg O’Reilly profiles a brave machine-gun officer. Just three of many interesting articles in our 64th edition of DIGGER. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

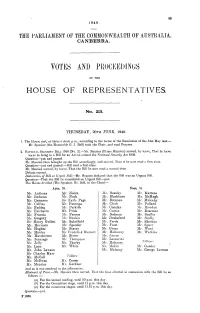

Votes And) Pi{Q0ceei)I Dngs

.1940. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF A1JSTRNLIA, CANBERRA. VOTES AND) PI{Q0CEEI)IDNGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. No. 23. THURSDAY, 20TH JUNE, 1940. 1. The Hlouse miet, ait three o'clock p.m., according to the terms of the Resolution of the 31st May last.- Mi'. Speaker (the Honorable Or. J. Bell) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2. NATIONAL SECURITY' BILL 1940 [No. 2].-Mr. Menzies (Prime Minister) moved, by leave, That he have leave to bring in a Bill for an Act to amend the National Secarity Act 1939. Question-put and passed. Mr. Menzies then brought up the Bill accordingly, and moved, That it be now read a first timie. Question-])ut and passed .- Bill read a first time. Mr. Menzies moved, by leave, That the Bill be now read a second timie. Debate ensued. Declaration of Bill as Urgent Bill.-Mr. Asenzies declared that the B1ill was an Urgent Bill. Question-That the B3ill he considered an Urgent Bill-pt. The House divided (The Speaker, Mr. Bell, in the Chair)- Ayes, 39. Noes, 31. M i . Anthony Mr. Nairn Beasley Mi'. Martens Mr. Badmnan Mr. Nock Mr'. Blackburn *Mr'. McHugh Mi'. Cameron Sir' Ear'le Page M r. Brennan Mr'. Mfulcahy M r. Collins Mr'. Paterson Clar k Mi' Pollard Conelan Mr. Rior'dan Mir. Fadden MI'. Perkii'% Mr. Mr. Fairbairn Mi' . Price Curtin A--Ir. Rlosevear Mri . Francis M.Prowse Mr'. Dedm an M~r. Scullin MALr. Gregory Ri.iankiin Mr. iDrakeford Mr'. Scully Sir Henry Gullett Mr'. Seliolfield Forde Mr. Sheehan Frost Mr. -

Ten Journeys to Cameron's Farm

Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm An Australian Tragedy Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm An Australian Tragedy Cameron Hazlehurst Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Hazlehurst, Cameron, 1941- author. Title: Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm / Cameron Hazlehurst. ISBN: 9781925021004 (paperback) 9781925021011 (ebook) Subjects: Menzies, Robert, Sir, 1894-1978. Aircraft accidents--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. World War, 1939-1945--Australia--History. Australia--Politics and government--1901-1945. Australia--Biography. Australia--History--1901-1945. Dewey Number: 320.994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press © Flaxton Mill House Pty Ltd 2013 and 2015 Cover design and layout © 2013 ANU E Press Cover design and layout © 2015 ANU Press Contents Part 1 Prologue 13 August 1940 . ix 1 . Augury . 1 2 . Leadership, politics, and war . 3 Part 2 The Journeys 3 . A crew assembles: Charlie Crosdale and Jack Palmer . 29 4 . Second seat: Dick Wiesener . 53 5 . His father’s son: Bob Hitchcock . 71 6 . ‘A very sound pilot’?: Bob Hitchcock (II) . 99 7 . Passenger complement . 131 8 . The General: Brudenell White (I) . 139 9 . Call and recall: Brudenell White (II) . 161 10 . The Brigadier: Geoff Street . 187 11 . -

Earle Page: an Active Treasurer

Earle Page: an active treasurer John Hawkins1 Earle Christmas Grafton Page brought down six Budgets while serving as Bruce’s treasurer. He was fortunate in when he was treasurer, after the war and before the Depression, which allowed him to ease tax burdens. Bruce and Page established the Loan Council and the National Debt Sinking Fund and introduced ‘tied grants’ to the States. Page moved the Commonwealth Bank further towards being a central bank and gave it responsibility for the note issue. Source: National Library of Australia 1 The author was formerly in Domestic Economy Division, the Australian Treasury. This article has benefited from discussions with Selwyn Cornish and the assistance of the Reserve Bank archivists. The views in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Australian Treasury. 55 Earle Page: an active treasurer Introduction As well as being a long-serving treasurer, Sir Earle Page PC GCMG served as prime minister for 20 days and was often acting prime minister. Only Billy Hughes has served a longer term in the House of Representatives. But as well as possessing longevity, Page was also innovative. His private secretary recalls him as ‘a combination of dreaming idealist and intensely practical man of affairs’.2 Indeed, he was described as ‘energetic, almost incoherent as he poured out ideas faster than words would come in an orderly fashion’, peppered with his trademark ‘you see, you see’.3 He not only had a lot of energy for his ideas and his politics. Physically robust, Page played a daily hard game of tennis until he was over 80, and ‘he played it as he played the political game, with reckless energy, native cunning and a certain contempt for the orthodox rules of the game’.4 His energy was accompanied by an ability to get on well with most of his colleagues. -

DALKIN, ROBERT NIXON (BOB) (1914–1991), Air Force Officer

D DALKIN, ROBERT NIXON (BOB) (1960–61), staff officer operations, Home (1914–1991), air force officer and territory Command (1957–59), and officer commanding administrator, was born on 21 February 1914 the RAAF Base, Williamtown, New South at Whitley Bay, Northumberland, England, Wales (1963). He had graduated from the RAF younger son of English-born parents George Staff College (1950) and the Imperial Defence Nixon Dalkin, rent collector, and his wife College (1962). Simultaneously, he maintained Jennie, née Porter. The family migrated operational proficiency, flying Canberra to Australia in 1929. During the 1930s bombers and Sabre fighters. Robert served in the Militia, was briefly At his own request Dalkin retired with a member of the right-wing New Guard, the rank of honorary air commodore from the and became business manager (1936–40) for RAAF on 4 July 1968 to become administrator W. R. Carpenter [q.v.7] & Co. (Aviation), (1968–72) of Norfolk Island. His tenure New Guinea, where he gained a commercial coincided with a number of important issues, pilot’s licence. Described as ‘tall, lean, dark including changes in taxation, the expansion and impressive [with a] well-developed of tourism, and an examination of the special sense of humour, and a natural, easy charm’ position held by islanders. (NAA A12372), Dalkin enlisted in the Royal Dalkin overcame a modest school Australian Air Force (RAAF) on 8 January education to study at The Australian National 1940 and was commissioned on 4 May. After University (BA, 1965; MA, 1978). Following a period instructing he was posted to No. 2 retirement, he wrote Colonial Era Cemetery of Squadron, Laverton, Victoria, where he Norfolk Island (1974) and his (unpublished) captained Lockheed Hudson light bombers on memoirs.