The Khartoum Process: Critical Assessment and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dave Meyer IES Abroad Rabat, Morocco Major: Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE)

Dave Meyer IES Abroad Rabat, Morocco Major: Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) Program: I participated in IES Abroad's program in Rabat, the capital city of Morocco. After a two week orientation in the city of Fez, we settled into Rabat for the remainder of the semester. I took courses in beginning Arabic, North African politics, Islam in Morocco, and gender in North Africa. All my classes were at the IES Center, which had several classrooms, wi-fi, and most importantly, air conditioning. The classes themselves were in English, but they were taught by English-speaking Moroccan professors. My program also arranged for us to go on several trips: a weekend in the Sahara desert, a weekend in the Middle Atlas mountains, and a trip to southern Spain to study Moorish culture. Typical Day: On a typical day, I would wake up around 7:15, get dressed, and head downstairs for breakfast prepared by most host mother, Batoul. Usually breakfast consisted of bread with butter, honey, and apricot jam and either coffee or Moroccan mint tea. After breakfast, I would start the 25 minute walk through the medina and city to class at the IES Center. Usually, the merchants in the medina were just setting up shop and traffic was busy as people arrived downtown for work. After Arabic class in the morning, I would head over to my favorite cafe, Cafe Al-Atlal, which was about two blocks from the center. There, I would enjoy an almond croissant and an espresso while reading for class, catching up on email, or just relaxing with my friends. -

Köppen Signatures” of Fossil Plant Assemblages for Effective Heat Transport of Gulf Stream to Subarctic North Atlantic During Miocene Cooling

Biogeosciences, 10, 7927–7942, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/7927/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-7927-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Evidence from “Köppen signatures” of fossil plant assemblages for effective heat transport of Gulf Stream to subarctic North Atlantic during Miocene cooling T. Denk1, G. W. Grimm1, F. Grímsson2, and R. Zetter2 1Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobiology, Box 50007, 10405 Stockholm, Sweden 2University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Correspondence to: T. Denk ([email protected]) Received: 8 July 2013 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 15 August 2013 Revised: 29 October 2013 – Accepted: 2 November 2013 – Published: 6 December 2013 Abstract. Shallowing of the Panama Sill and the closure 1 Introduction of the Central American Seaway initiated the modern Loop Current–Gulf Stream circulation pattern during the Miocene, The Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO) at 17–15 but no direct evidence has yet been provided for effec- million years (Myr) was the last phase of markedly warm cli- tive heat transport to the northern North Atlantic during mate in the Cenozoic (Zachos et al., 2001). The MMCO was that time. Climatic signals from 11 precisely dated plant- followed by the Mid-Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT) bearing sedimentary rock formations in Iceland, spanning at 14.2–13.8 Myr correlated with the growth of the East 15–0.8 million years (Myr), resolve the impacts of the devel- Antarctic Ice Sheet (Shevenell et al., 2004). In the Northern oping Miocene global thermohaline circulation on terrestrial Hemisphere this cooling is reflected by continuous sea ice in vegetation in the subarctic North Atlantic region. -

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021)

Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Abidjan CR1 10 Abidjan DV 8 Abidjan F1 5 Abidjan F2B 1 Abidjan F4 8 Abidjan FX 33 Abidjan IR1 10 Abidjan IR2 18 Abidjan IR5 14 Abu Dhabi CR1 39 Abu Dhabi DV 29 Abu Dhabi E1 1 Abu Dhabi E3 81 Abu Dhabi F1 14 Abu Dhabi F2B 7 Abu Dhabi F3 12 Abu Dhabi F4 60 Abu Dhabi FX 16 Abu Dhabi I5 3 Abu Dhabi IR1 89 Abu Dhabi IR2 17 Abu Dhabi IR5 84 Abu Dhabi SB1 9 Abu Dhabi SE 4 Accra CR1 1 Accra E3 15 Accra F1 15 Accra F2B 4 Accra F3 22 Accra F4 13 Accra FX 23 Accra IR1 35 Accra IR2 48 Accra IR5 41 Accra SB1 9 Accra SE 32 Addis Ababa CR1 17 Addis Ababa DV 9 Addis Ababa E1 1 Addis Ababa F1 12 Addis Ababa F2B 13 Addis Ababa F3 5 Page 1 of 34 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Addis Ababa FX 125 Addis Ababa IR1 90 Addis Ababa IR2 83 Addis Ababa IR5 47 Addis Ababa SB1 4 Addis Ababa SE 57 AIT Taipei DV 2 AIT Taipei E1 6 AIT Taipei E2 18 AIT Taipei E3 5 AIT Taipei EW 1 AIT Taipei F1 15 AIT Taipei F2B 1 AIT Taipei F3 12 AIT Taipei F4 92 AIT Taipei FX 36 AIT Taipei I5 33 AIT Taipei IR1 11 AIT Taipei IR2 6 AIT Taipei IR3 7 AIT Taipei IR5 30 AIT Taipei SB1 30 Algiers CR1 26 Algiers DV 45 Algiers F4 2 Algiers FX 23 Algiers IR1 42 Algiers IR2 9 Algiers IR5 30 Algiers SE 5 Almaty CR1 1 Almaty DV 134 Almaty E3 4 Almaty F1 1 Almaty F2B 1 Almaty FX 49 Almaty IB1 1 Almaty IR1 4 Almaty IR2 6 Almaty IR5 58 Amman CR1 8 Amman CR2 1 Page 2 of 34 Immigrant Visa Issuances by Post June 2021 (FY 2021) Post Visa Class Issuances Amman DV 57 Amman E2 6 Amman -

Rabat and Salé – Bridging the Gap Nchimunya Hamukoma, Nicola Doyle and Archimedes Muzenda

FUTURE OF AFRICAN CITIES PROJECT DISCUSSION PAPER 13/2018 Rabat and Salé – Bridging the Gap Nchimunya Hamukoma, Nicola Doyle and Archimedes Muzenda Strengthening Africa’s economic performance Rabat and Salé – Bridging the Gap Contents Executive Summary .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Setting the Scene .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 The Security Imperative .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 Governance .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 Economic Growth .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 Infrastructure .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Service Delivery .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 16 Conclusion .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 Endnotes .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 About the Authors Nchimunya Hamukoma and Published in November 2018 by The Brenthurst Foundation Nicola Doyle are Researchers The Brenthurst Foundation at the Brenthurst Foundation. (Pty) Limited Archimedes Muzenda was the PO Box 61631, Johannesburg 2000, South Africa Machel-Mandela Fellow for Tel +27-(0)11 274-2096 2018. Fax +27-(0)11 274-2097 www.thebrenthurstfoundation.org -

Study Abroad

STUDY ABROAD STUDENT GUIDE TAP INTO THE POWER OF STUDY ABROAD Be prepared to, meet new people, discover a new perspective, and learn new skills. You will return with a new outlook on your academic and future professional life – guaranteed. found employment within 12 months of 97% graduation earned higher salaries 25% than their peers built valuable skills for the 84% job market saw greater improvement 100% in GPA post-study abroad 96% felt more self-confident *University of California Merced, What Statistics Show about Study Abroad Students studyabroad.ucmerced.edu/study-abroad-statistics/statistics-study-abroad 4 YOUR BEST CHOICE FOR STUDY ABROAD The provider you choose can make all the difference. As the nonprofit world leader in international education, CIEE has been changing students’ lives for more than 75 years. With CIEE you can count on… ɨ One-on-one guidance from CIEE staff from pre-departure through your return home ɨ Best-in-class, culturally rich, high-quality, engaging academics ɨ Co-curricular activities and excursions included ɨ One easy application for access to more merit and need-based funding per term than any other provider ɨ Comprehensive health, safety, and security protocols Study Abroad 150+ Programs Sites Around 30+ the World Years as International 75+ Education Leader LEARN MORE ciee.org/study 5 YEAR-ROUND FLEXIBLE PROGRAM OPTIONS BERLIN No matter what your area of study, academic schedule, or budget, CIEE has a study abroad program that’s right for you. Open Campus Block Programs Our most flexible study abroad option that combines CAPE TOWN six-week blocks at one, two or three cities. -

Les Migrations Internationales Ouest-Africaines

COMMISSION DE LA CEDEAO ECOWAS COMMISSION ECOWAS JOINT APPROACH ON MIGRATION Experts meeting Dakar, 11 – 12 April 2007 1 2 Table of contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 5 I. ECOWAS JOINT APPROACH ON MIGRATION ................................................... 5 1.1 The Institutional Framework .......................................................................... 5 1.2 The Principles ................................................................................................. 6 1) Free movement of persons within the ECOWAS zone is one of the fundamental priorities of political integration of ECOWAS member States. .................................... 6 2) Legal migration towards other regions of the world contributes to ECOWAS member States‟ development. ......................................................................................... 6 3) Combating human trafficking is a moral and humanitarian imperative of ECOWAS member States. ................................................................................................ 6 4) Harmonising policies. ..................................................................................... 6 II. MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT ACTION PLANS ............................................ 7 2.1 Actions promoting free movement within the ECOWAS zone ........................... 7 Implementation of the Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, the Right of Residence and Establishment ............................................................................................ -

The Politics of Euro-Mediterranean Regional Identity and Migration Governance

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2020 United or Divided? The Politics of Euro-Mediterranean Regional Identity and Migration Governance Sarah Hall SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, International Relations Commons, Migration Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Sarah, "United or Divided? The Politics of Euro-Mediterranean Regional Identity and Migration Governance" (2020). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3365. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3365 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. United or Divided? The Politics of Euro-Mediterranean Regional Identity and Migration Governance Hall, Sarah Academic Director: Belghazi, Taieb Academic Adviser: Chegraoui, Khalid Brown University Politics & Economics Rabat, Morocco, Africa Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for Morocco: Multiculturalism and Human Rights, SIT Study Abroad, Spring 2020 Abstract Migration management has become one of the foremost global governance challenges facing states -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

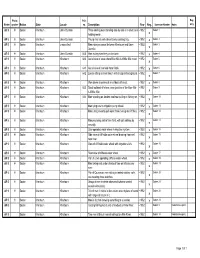

State Locale Description Year Neg. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Three Smiling Men Standing Side by Side in Market, One Hold

Photo- Print Neg. Binder grapher Nation State Locale no. Description Year Neg. Sorenson Number Notes only AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Three smiling men standing side by side in market, one ~1952 Sudan 1 x holding melon. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān Young man at work decoratively painting tray. ~1952 x Sudan 2 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum unspecified Man riding on camel between Khartoum and Umm ~1952 Sudan 3 x Durmān. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Umm Durmān 645 Men exiting river ferry on to shore. ~1952 x Sudan 4 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 640 Aerial view of area where Blue Nile & White Nile meet. ~1952 Sudan 5 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 641 Aerial view of riverside farm fields. ~1952 x Sudan 6 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 642 Locals sitting on river beach with bridge in background. ~1952 Sudan 7 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum View down shoreline of small boat off coast. ~1952 x Sudan 8 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 643 Small sailboat off shore, near junction of the Blue Nile ~1952 Sudan 9 x & White Nile. AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum 644 Man standing on docked row boat pulling in fishing net. ~1952 Sudan 10 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man tying cow to irrigation pump wheel. ~1952 x Sudan 11 AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man using levee to pull water from river up to cliff face. ~1952 Sudan 12 x AF 5 H Sudan Khartoum Khartoum Man preparing soil in farm field, with girl walking by ~1952 Sudan 13 x casually. -

Arabic Across North Africa

Study Abroad Christine Tsai samples Arabic immersion programs from both ends of the Mediterranean Sea Arabic across North Africa Colloquial Arabic, the most widely understood dialect, Egypt colloquial Arabic. In addition, Cairo offers spe- classical On the North coast of Africa with the cial programs for Arabic teachers and journal- Arabic, Sinai Peninsula connecting it to Western Asia, ists. The Amman, Jordan private instructional Arabic jour- Egypt has more than 82 million inhabitants. program can be tailored to all needs including nalism, and Known for its ancient monuments, such as the Diplomatic Arabic. For those involved in bank- Islamic religion Giza Pyramids and the Great Sphinx, count- ing, the petroleum industry or construction, all taught in less travelers visit Egypt each year to marvel at Oman is a great place to learn Gulf Arabic. Arabic. Situated in a its history and culture. Whether students visit Finally, AmeriSpan offers a summer program very quiet area in the Saudiya Buildings near the ancient artifacts in Luxor, the Royal Library for teenagers in Rabat, Morocco. the quarter of Heliopolis, the center guaran- in Alexandria, or the bustling modern capital of Located in one of the oldest and most tees students the right setting for study. Cairo, they will be guaranteed a full cultural exciting cities in the world, the American Also in Cairo, the Drayah Language Egyptian immersion experience. University in Cairo was founded 90 years Center seeks to give learners an overview of Following the Arab-Muslim conquest of Egypt in ago to provide a U.S.-style liberal arts educa- the customs and traditions of Egyptian culture the 7th century AD, Egyptians slowly adopted tion to young Egyptians. -

The Stable Isotope Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East

water Article The Stable Isotope Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East Highlighting the Link between the Köppen Climate Classifications and the δ18O and δ2H Values of Precipitation Mojtaba Heydarizad 1, Luis Gimeno 1,*, Rogert Sorí 1,2 , Foad Minaei 3,4 and Javad Eskandari Mayvan 5 1 Centro de Investigación Mariña, Environmental Physics Laboratory (EPhysLab), Campus As Lagoas s/n, Universidade de Vigo, 32004 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (R.S.) 2 Instituto Dom Luiz (IDL), Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal 3 Department of Geography, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad 917794883, Iran; [email protected] 4 Geographic Information Science/System and Remote Sensing Laboratory (GISSRS. Lab), Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad 9177794883, Iran 5 Regional Water Company of Khorasan Razavi, Mashhad 9185916196, Iran; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Middle East is faced with a water shortage crisis due to its semiarid and arid climate. In this paper, precipitation as an important part of the water cycle was evaluated in 43 stations across the Middle East using the stable isotope technique to study the parameters which influence the stable isotope content of precipitation. First, the stepwise regression model was applied to determine the Citation: Heydarizad, M.; main geographical and climatological factors affecting the stable isotopes in precipitation. Secondly, Gimeno, L.; Sorí, R.; Minaei, F.; the stepwise model was also used to simulate the stable isotope values in precipitation. Furthermore, Mayvan, J.E. The Stable Isotope due to the notable climatic variations across the Middle East, the precipitation sampling stations Characteristics of Precipitation in the Middle East Highlighting the Link were classified into six groups based on the Köppen climate zones.