The Politics of Euro-Mediterranean Regional Identity and Migration Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dave Meyer IES Abroad Rabat, Morocco Major: Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE)

Dave Meyer IES Abroad Rabat, Morocco Major: Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) Program: I participated in IES Abroad's program in Rabat, the capital city of Morocco. After a two week orientation in the city of Fez, we settled into Rabat for the remainder of the semester. I took courses in beginning Arabic, North African politics, Islam in Morocco, and gender in North Africa. All my classes were at the IES Center, which had several classrooms, wi-fi, and most importantly, air conditioning. The classes themselves were in English, but they were taught by English-speaking Moroccan professors. My program also arranged for us to go on several trips: a weekend in the Sahara desert, a weekend in the Middle Atlas mountains, and a trip to southern Spain to study Moorish culture. Typical Day: On a typical day, I would wake up around 7:15, get dressed, and head downstairs for breakfast prepared by most host mother, Batoul. Usually breakfast consisted of bread with butter, honey, and apricot jam and either coffee or Moroccan mint tea. After breakfast, I would start the 25 minute walk through the medina and city to class at the IES Center. Usually, the merchants in the medina were just setting up shop and traffic was busy as people arrived downtown for work. After Arabic class in the morning, I would head over to my favorite cafe, Cafe Al-Atlal, which was about two blocks from the center. There, I would enjoy an almond croissant and an espresso while reading for class, catching up on email, or just relaxing with my friends. -

Rabat and Salé – Bridging the Gap Nchimunya Hamukoma, Nicola Doyle and Archimedes Muzenda

FUTURE OF AFRICAN CITIES PROJECT DISCUSSION PAPER 13/2018 Rabat and Salé – Bridging the Gap Nchimunya Hamukoma, Nicola Doyle and Archimedes Muzenda Strengthening Africa’s economic performance Rabat and Salé – Bridging the Gap Contents Executive Summary .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Setting the Scene .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 The Security Imperative .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 Governance .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 Economic Growth .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 Infrastructure .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Service Delivery .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 16 Conclusion .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 Endnotes .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 About the Authors Nchimunya Hamukoma and Published in November 2018 by The Brenthurst Foundation Nicola Doyle are Researchers The Brenthurst Foundation at the Brenthurst Foundation. (Pty) Limited Archimedes Muzenda was the PO Box 61631, Johannesburg 2000, South Africa Machel-Mandela Fellow for Tel +27-(0)11 274-2096 2018. Fax +27-(0)11 274-2097 www.thebrenthurstfoundation.org -

Study Abroad

STUDY ABROAD STUDENT GUIDE TAP INTO THE POWER OF STUDY ABROAD Be prepared to, meet new people, discover a new perspective, and learn new skills. You will return with a new outlook on your academic and future professional life – guaranteed. found employment within 12 months of 97% graduation earned higher salaries 25% than their peers built valuable skills for the 84% job market saw greater improvement 100% in GPA post-study abroad 96% felt more self-confident *University of California Merced, What Statistics Show about Study Abroad Students studyabroad.ucmerced.edu/study-abroad-statistics/statistics-study-abroad 4 YOUR BEST CHOICE FOR STUDY ABROAD The provider you choose can make all the difference. As the nonprofit world leader in international education, CIEE has been changing students’ lives for more than 75 years. With CIEE you can count on… ɨ One-on-one guidance from CIEE staff from pre-departure through your return home ɨ Best-in-class, culturally rich, high-quality, engaging academics ɨ Co-curricular activities and excursions included ɨ One easy application for access to more merit and need-based funding per term than any other provider ɨ Comprehensive health, safety, and security protocols Study Abroad 150+ Programs Sites Around 30+ the World Years as International 75+ Education Leader LEARN MORE ciee.org/study 5 YEAR-ROUND FLEXIBLE PROGRAM OPTIONS BERLIN No matter what your area of study, academic schedule, or budget, CIEE has a study abroad program that’s right for you. Open Campus Block Programs Our most flexible study abroad option that combines CAPE TOWN six-week blocks at one, two or three cities. -

Les Migrations Internationales Ouest-Africaines

COMMISSION DE LA CEDEAO ECOWAS COMMISSION ECOWAS JOINT APPROACH ON MIGRATION Experts meeting Dakar, 11 – 12 April 2007 1 2 Table of contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 5 I. ECOWAS JOINT APPROACH ON MIGRATION ................................................... 5 1.1 The Institutional Framework .......................................................................... 5 1.2 The Principles ................................................................................................. 6 1) Free movement of persons within the ECOWAS zone is one of the fundamental priorities of political integration of ECOWAS member States. .................................... 6 2) Legal migration towards other regions of the world contributes to ECOWAS member States‟ development. ......................................................................................... 6 3) Combating human trafficking is a moral and humanitarian imperative of ECOWAS member States. ................................................................................................ 6 4) Harmonising policies. ..................................................................................... 6 II. MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT ACTION PLANS ............................................ 7 2.1 Actions promoting free movement within the ECOWAS zone ........................... 7 Implementation of the Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, the Right of Residence and Establishment ............................................................................................ -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

Arabic Across North Africa

Study Abroad Christine Tsai samples Arabic immersion programs from both ends of the Mediterranean Sea Arabic across North Africa Colloquial Arabic, the most widely understood dialect, Egypt colloquial Arabic. In addition, Cairo offers spe- classical On the North coast of Africa with the cial programs for Arabic teachers and journal- Arabic, Sinai Peninsula connecting it to Western Asia, ists. The Amman, Jordan private instructional Arabic jour- Egypt has more than 82 million inhabitants. program can be tailored to all needs including nalism, and Known for its ancient monuments, such as the Diplomatic Arabic. For those involved in bank- Islamic religion Giza Pyramids and the Great Sphinx, count- ing, the petroleum industry or construction, all taught in less travelers visit Egypt each year to marvel at Oman is a great place to learn Gulf Arabic. Arabic. Situated in a its history and culture. Whether students visit Finally, AmeriSpan offers a summer program very quiet area in the Saudiya Buildings near the ancient artifacts in Luxor, the Royal Library for teenagers in Rabat, Morocco. the quarter of Heliopolis, the center guaran- in Alexandria, or the bustling modern capital of Located in one of the oldest and most tees students the right setting for study. Cairo, they will be guaranteed a full cultural exciting cities in the world, the American Also in Cairo, the Drayah Language Egyptian immersion experience. University in Cairo was founded 90 years Center seeks to give learners an overview of Following the Arab-Muslim conquest of Egypt in ago to provide a U.S.-style liberal arts educa- the customs and traditions of Egyptian culture the 7th century AD, Egyptians slowly adopted tion to young Egyptians. -

Overview Courses Cities

DIPLOMACY & HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN BELGIUM • MOROCCO • TUNISIA • FRANCE JANUARY TERM Diplomacy is about balancing multiple, sometimes competing priorities. How can the US promote human rights in North Africa while also fighting terrorism? How does the US elicit cooperation from NATO allies while also getting them to pay their fair share? This study tour surveys how US diplomats balance multiple goals and foreign policy challenges while working with partners from other governments, international organizations, and civil society in Europe and North Africa. The Mediterranean region is one where the most pressing foreign policy challenges of the day converge, from migration to counterterrorism and climate change to great power competition with China and Russia. This course will introduce students to the tools the US uses to address these challenges, from public overview diplomacy to military partnerships. Students choose one of the following courses: • Human Development 355: Diplomacy & Human Rights in the Mediterranean • Human Rights 355: Diplomacy & Human Rights in the Mediterranean • International Relations 355: Diplomacy & Human Rights in the Mediterranean • Political Science 355: Diplomacy & Human Rights in the Mediterranean courses Morocco: Rabat Tunisia: Tunis, Carthage France: Aix-en-Provence, Marseille, and Paris Belgium: Brussels cities [email protected] | 800-221-2051 | www.iau.edu DIPLOMACY & HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN DECEMBER 29, 2020 - JANUARY 15, 2021 JANUARY TERM SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Dec. 28 Dec. 29 Calendar tentativeDec. 30 and subject to change.Dec. 31 Jan. 1 Jan. 2 Depart for Brussels Arrival in Brussels Brussels Brussels Brussels Brussels / Paris • Orientation • NATO Visit • Lecture • Lecture • Train Brussels to • Welcome Dinner • Parlamentarium • European • Cultural Activities Paris Museum Parliament • Museum Visit • NYE Dinner Jan. -

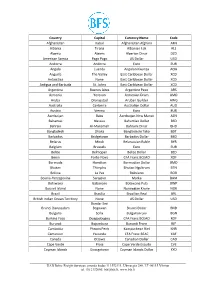

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Rabat Declaration the Participants from African Countries, Namely Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso

Rabat Declaration The participants from African countries, namely Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Cote d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Senegal, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and from the government of Japan, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the City of Yokohama, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), African Development Bank (AfDB), having met at the first Annual Meeting of the African Clean Cities Platform in Rabat, Kingdom of Morocco from 26 to 28 June 2018, Taking note of the Maputo Declaration, adopted at the Preparatory Meeting of the African Clean Cities Platform in Maputo, Mozambique held from 25th to 27th April 2017, which endorsed the inauguration of the African Clean Cities Platform, Reaffirming our commitments to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the African Union’s Agenda 2063 – The Africa We Want, Noting with satisfaction and recognizing the significant contribution of the Kingdom of Morocco for hosting the first Annual Meeting of the African Clean Cities Platform, Welcoming participants who have newly joined the African Clean Cities Platform since the Preparatory Meeting in Maputo in 2017, Noting that proper waste management not only addresses -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

War Narrative Credits: 3

GENERAL STUDIES COURSE PROPOSAL COVER FORM (ONE COURSE PER FORM) 1.) DATE: 3/26/19 2.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE: Maricopa Co. Comm. College District 3.) PROPOSED COURSE: Prefix: ENH Number: 277AE Title: Tour of Duty: War Narrative Credits: 3 CROSS LISTED WITH: Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: . 4.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE INITIATOR: KEITH ANDERSON PHONE: 480-654-7300 EMAIL: [email protected] ELIGIBILITY: Courses must have a current Course Equivalency Guide (CEG) evaluation. Courses evaluated as NT (non- transferable are not eligible for the General Studies Program. MANDATORY REVIEW: The above specified course is undergoing Mandatory Review for the following Core or Awareness Area (only one area is permitted; if a course meets more than one Core or Awareness Area, please submit a separate Mandatory Review Cover Form for each Area). POLICY: The General Studies Council (GSC) Policies and Procedures requires the review of previously approved community college courses every five years, to verify that they continue to meet the requirements of Core or Awareness Areas already assigned to these courses. This review is also necessary as the General Studies program evolves. AREA(S) PROPOSED COURSE WILL SERVE: A course may be proposed for more than one core or awareness area. Although a course may satisfy a core area requirement and an awareness area requirement concurrently, a course may not be used to satisfy requirements in two core or awareness areas simultaneously, even if approved for those areas. With departmental consent, an approved General Studies course may be counted toward both the General Studies requirements and the major program of study. -

FINAL DECLARATION on Africa and Migration

AFRICAN PARLIAMENTARY UNION B.P.V 314 Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Web Site : http://www.african-pu.org African Parliamentary Conference “Africa and Migration: challenges, problems and solutions” (Rabat, the Kingdom of Morocco, 22-24 May 2008) FINAL DECLARATION National parliaments of Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Gambia, Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa and Zimbabwe, Having met in Rabat on the invitation of the House of Representatives and the House of Councilors of the Kingdom of Morocco, from 22 to 24 May 2008, at the Conference on “Africa and Migration: Challenges, Problems and Solutions”, organized by the African Parliamentary Union (APU) in cooperation with the Inter-parliamentary Union (IPU), with the support of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the United Nations Office of the High-Commissioner for Human Rights, (OHCHR) the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and chaired by the Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Kingdom of Morocco, the Honourable Mustapha Mansouri, Recalling: § The first EU-AU Ministerial Conference on Migration and Development held in Rabat from 10 to 11 July 2006; § The African Common Position on Migration and Development adopted by the Assembly of the African Union in Banjul in July 2006; § The Joint Africa-EU