Chapter 5 Conclusions 212

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosette Nebula and Monoceros Loop

Oshkosh Scholar Page 43 Studying Complex Star-Forming Fields: Rosette Nebula and Monoceros Loop Chris Hathaway and Anthony Kuchera, co-authors Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva, Physics and Astronomy, faculty adviser Christopher Hathaway obtained a B.S. in physics in 2007 and is currently pursuing his masters in physics education at UW Oshkosh. He collaborated with Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva on his senior research project and presented their findings at theAmerican Astronomical Society meeting (2008), the Celebration of Scholarship at UW Oshkosh (2009), and the National Conference on Undergraduate Research in La Crosse, Wisconsin (2009). Anthony Kuchera graduated from UW Oshkosh in May 2008 with a B.S. in physics. He collaborated with Dr. Kaltcheva from fall 2006 through graduation. He presented his astronomy-related research at Posters in the Rotunda (2007 and 2008), the Wisconsin Space Conference (2007), the UW System Symposium for Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity (2007 and 2008), and the American Astronomical Society’s 211th meeting (2008). In December 2009 he earned an M.S. in physics from Florida State University where he is currently working toward a Ph.D. in experimental nuclear physics. Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva is a professor of physics and astronomy. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Sofia in Bulgaria. She joined the UW Oshkosh Physics and Astronomy Department in 2001. Her research interests are in the field of stellar photometry and its application to the study of Galactic star-forming fields and the spiral structure of the Milky Way. Abstract An investigation that presents a new analysis of the structure of the Northern Monoceros field was recently completed at the Department of Physics andAstronomy at UW Oshkosh. -

Spatial and Kinematic Structure of Monoceros Star-Forming Region

MNRAS 476, 3160–3168 (2018) doi:10.1093/mnras/sty447 Advance Access publication 2018 February 22 Spatial and kinematic structure of Monoceros star-forming region M. T. Costado1‹ and E. J. Alfaro2 1Departamento de Didactica,´ Universidad de Cadiz,´ E-11519 Puerto Real, Cadiz,´ Spain. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/476/3/3160/4898067 by Universidad de Granada - Biblioteca user on 13 April 2020 2Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, CSIC, Apdo 3004, E-18080 Granada, Spain Accepted 2018 February 9. Received 2018 February 8; in original form 2017 December 14 ABSTRACT The principal aim of this work is to study the velocity field in the Monoceros star-forming region using the radial velocity data available in the literature, as well as astrometric data from the Gaia first release. This region is a large star-forming complex formed by two associations named Monoceros OB1 and OB2. We have collected radial velocity data for more than 400 stars in the area of 8 × 12 deg2 and distance for more than 200 objects. We apply a clustering analysis in the subspace of the phase space formed by angular coordinates and radial velocity or distance data using the Spectrum of Kinematic Grouping methodology. We found four and three spatial groupings in radial velocity and distance variables, respectively, corresponding to the Local arm, the central clusters forming the associations and the Perseus arm, respectively. Key words: techniques: radial velocities – astronomical data bases: miscellaneous – parallaxes – stars: formation – stars: kinematics and dynamics – open clusters and associations: general. Hoogerwerf & De Bruijne 1999;Lee&Chen2005; Lombardi, 1 INTRODUCTION Alves & Lada 2011). -

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

How to Make $1000 with Your Telescope! – 4 Stargazers' Diary

Fort Worth Astronomical Society (Est. 1949) February 2010 : Astronomical League Member Club Calendar – 2 Opportunities & The Sky this Month – 3 How to Make $1000 with your Telescope! – 4 Astronaut Sally Ride to speak at UTA – 4 Aurgia the Charioteer – 5 Stargazers’ Diary – 6 Bode’s Galaxy by Steve Tuttle 1 February 2010 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 Algol at Minima Last Qtr Moon Æ 5:48 am 11:07 pm Top ten binocular deep-sky objects for February: M35, M41, M46, M47, M50, M93, NGC 2244, NGC 2264, NGC 2301, NGC 2360 Top ten deep-sky objects for February: M35, M41, M46, M47, M50, M93, NGC 2261, NGC 2362, NGC 2392, NGC 2403 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Algol at Minima Morning sports a Moon at Apogee New Moon Æ super thin crescent (252,612 miles) 8:51 am 7:56 pm Moon 8:00 pm 3RF Star Party Make use of the New Moon Weekend for . better viewing at the Dark Sky Site See Notes Below New Moon New Moon Weekend Weekend 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Presidents Day 3RF Star Party Valentine’s Day FWAS Traveler’s Guide Meeting to the Planets UTA’s Maverick Clyde Tombaugh Ranger 8 returns Normal Room premiers on Speakers Series discovered Pluto photographs and NatGeo 7pm Sally Ride “Fat Tuesday” Ash Wednesday 80 years ago. impacts Moon. 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Algol at Minima First Qtr Moon Moon at Perigee Å (222,345 miles) 6:42 pm 12:52 am 4 pm {Low in the NW) Algol at Minima Æ 9:43 pm Challenge binary star for month: 15 Lyncis (Lynx) Challenge deep-sky object for month: IC 443 (Gemini) Notable carbon star for month: BL Orionis (Orion) 28 Notes: Full Moon Look for a very thin waning crescent moon perched just above and slightly right of tiny Mercury on the morning of 10:38 pm Feb. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

April's Total Lunar Eclipse by Steve Mastellotto

April’s Total Lunar Eclipse by Steve Mastellotto Volume 39, No. 6 of Canada - Windsor Centre A lunar eclipse occurs when the Sun, Earth, and the Moon line up. In early morning hours of Tues- day April 15th the full moon will pass through Earth’s shadow for most of North America. Earth ’s shadow has two parts: a darker inner section called the umbra and a lighter outer region called the penumbra. When all of the Moon passes through the umbra we get a total lunar eclipse. That’s what’s happening on the 15th and Windsor is in a prime location so see the entire event. The early stage begins with the generally unobservable penumbral phase at 12:52 a.m.. The moon begins to enter the umbral portion of the shadow at 1:57 a.m. marking the beginning of the partial phase of the eclipse. At 3:06 a.m. the moon will be fully immersed in the Earth’s shadow and totality be- gins. Since the Earth’s shadow is almost 3 times as large as the moon it can take up to 90 minutes for the moon to travel through the Earth’s umbra. Since this eclipse is not exactly centered in the Earth’s shadow totality will last about 78 minutes. You should look for the changing colour of the moon during totality which can vary from light gray to a deep red. Most eclipses have an orange appearance. As noted since the moon will be passing through the lower half of the Earth’s shadow the eclipse will look darkest on the top of the moon. -

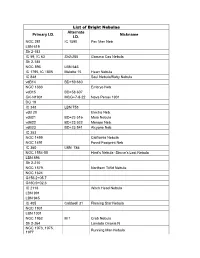

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Open Clusters

Open Clusters Open clusters (also known as galactic clusters) are of tremendous importance to the science of astronomy, if not to astrophysics and cosmology generally. Star clusters serve as the "laboratories" of astronomy, with stars now all at nearly the same distance and all created at essentially the same time. Each cluster thus is a running experiment, where we can observe the effects of composition, age, and environment. We are hobbled by seeing only a snapshot in time of each cluster, but taken collectively we can understand their evolution, and that of their included stars. These clusters are also important tracers of the Milky Way and other parent galaxies. They help us to understand their current structure and derive theories of the creation and evolution of galaxies. Just as importantly, starting from just the Hyades and the Pleiades, and then going to more distance clusters, open clusters serve to define the distance scale of the Milky Way, and from there all other galaxies and the entire universe. However, there is far more to the study of star clusters than that. Anyone who has looked at a cluster through a telescope or binoculars has realized that these are objects of immense beauty and symmetry. Whether a cluster like the Pleiades seen with delicate beauty with the unaided eye or in a small telescope or binoculars, or a cluster like NGC 7789 whose thousands of stars are seen with overpowering wonder in a large telescope, open clusters can only bring awe and amazement to the viewer. These sights are available to all. -

The Evening Sky

I N E D R I A C A S T N E O D I T A C L E O R N I G D S T S H A E P H M O O R C I . Z N O e d b l A a r , a l n e O , g N i C R a , Z p s e u I l i C l r a i , R I S C f R a O o s C t p H o L u r E e E & d H P a ( o T F m l O l s u i D R NORTH x ” , N M n E a A o n O X g d A H a x C P M T e r . I o P Polaris H N c S L r y E E e o P Z t n “ n E . EQUATORIAL EDITION i A N H O W T M “ R e T Y N H h E T ” K E ) W S . T T E U W B R N The Evening Sky Map W D E T T . FEBRUARY 2011 WH r A e E C t M82 FREE* EACH MONTH FOR YOU TO EXPLORE, LEARN & ENJOY THE NIGHT SKY O s S L u K l T Y c E CASSIOPEIA h R e r M a A S t A SKY MAP SHOWS HOW i s η M81 Get Sky Calendar on Twitter S P c T s k C A l e e E CAMELOPARDALIS R d J Sky Calendar – February 2011 a O http://twitter.com/skymaps i THE NIGHT SKY LOOKS s B y U O a H N L s D e t A h NE a I t I EARLY FEB 9 PM r T T f S p 1 Moon near Mercury (16° from Sun, morning sky) at 17h UT. -

SAA 100 Club

S.A.A. 100 Observing Club Raleigh Astronomy Club Version 1.2 07-AUG-2005 Introduction Welcome to the S.A.A. 100 Observing Club! This list started on the USENET newsgroup sci.astro.amateur when someone asked about everyone’s favorite, non-Messier objects for medium sized telescopes (8-12”). The members of the group nominated objects and voted for their favorites. The top 100 objects, by number of votes, were collected and ranked into a list that was published. This list is a good next step for someone who has observed all the objects on the Messier list. Since it includes objects in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres (DEC +72 to -72), the award has two different levels to accommodate those observers who aren't able to travel. The first level, the Silver SAA 100 award requires 88 objects (all visible from North Carolina). The Gold SAA 100 Award requires all 100 objects to be observed. One further note, many of these objects are on other observing lists, especially Patrick Moore's Caldwell list. For convenience, there is a table mapping various SAA100 objects with their Caldwell counterparts. This will facilitate observers who are working or have worked on these lists of objects. We hope you enjoy looking at all the great objects recommended by other avid astronomers! Rules In order to earn the Silver certificate for the program, the applicant must meet the following qualifications: 1. Be a member in good standing of the Raleigh Astronomy Club. 2. Observe 80 Silver observations. 3. Record the time and date of each observation. -

Caldwell Catalogue - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Caldwell catalogue - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Caldwell catalogue From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents The Caldwell Catalogue is an astronomical catalog of 109 bright star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies for observation by amateur astronomers. The list was compiled Featured content by Sir Patrick Caldwell-Moore, better known as Patrick Moore, as a complement to the Messier Catalogue. Current events The Messier Catalogue is used frequently by amateur astronomers as a list of interesting deep-sky objects for observations, but Moore noted that the list did not include Random article many of the sky's brightest deep-sky objects, including the Hyades, the Double Cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884), and NGC 253. Moreover, Moore observed that the Donate to Wikipedia Messier Catalogue, which was compiled based on observations in the Northern Hemisphere, excluded bright deep-sky objects visible in the Southern Hemisphere such [1][2] Interaction as Omega Centauri, Centaurus A, the Jewel Box, and 47 Tucanae. He quickly compiled a list of 109 objects (to match the number of objects in the Messier [3] Help Catalogue) and published it in Sky & Telescope in December 1995. About Wikipedia Since its publication, the catalogue has grown in popularity and usage within the amateur astronomical community. Small compilation errors in the original 1995 version Community portal of the list have since been corrected. Unusually, Moore used one of his surnames to name the list, and the catalogue adopts "C" numbers to rename objects with more Recent changes common designations.[4] Contact Wikipedia As stated above, the list was compiled from objects already identified by professional astronomers and commonly observed by amateur astronomers. -

The Angular Size of Objects in the Sky

APPENDIX 1 The Angular Size of Objects in the Sky We measure the size of objects in the sky in terms of degrees. The angular diameter of the Sun or the Moon is close to half a degree. There are 60 minutes (of arc) to one degree (of arc), and 60 seconds (of arc) to one minute (of arc). Instead of including – of arc – we normally just use degrees, minutes and seconds. 1 degree = 60 minutes. 1 minute = 60 seconds. 1 degree = 3,600 seconds. This tells us that the Rosette nebula, which measures 80 minutes by 60 minutes, is a big object, since the diameter of the full Moon is only 30 minutes (or half a degree). It is clearly very useful to know, by looking it up beforehand, what the angular size of the objects you want to image are. If your field of view is too different from the object size, either much bigger, or much smaller, then the final image is not going to look very impressive. For example, if you are using a Sky 90 with SXVF-M25C camera with a 3.33 by 2.22 degree field of view, it would not be a good idea to expect impressive results if you image the Sombrero galaxy. The Sombrero galaxy measures 8.7 by 3.5 minutes and would appear as a bright, but very small patch of light in the centre of your frame. Similarly, if you were imaging at f#6.3 with the Nexstar 11 GPS scope and the SXVF-H9C colour camera, your field of view would be around 17.3 by 13 minutes, NGC7000 would not be the best target.