Northern States Bald Eagle Recovery Plan 40 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

First Session- Thirty-Seventh Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable George Hickes Speaker .. ....... ·.. ·· -·� Vol. L No. 36 - 1:30 p.m., Tuesday, May 30, 2000 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Seventh Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation AGLUGUB, Cris The Maples N.D.P. ALLAN, Nancy St. Vital N.D.P. ASHTON, Steve, Hon. Thompson N.D.P. ASPER, Linda Riel N.D.P. BARRETT, Becky, Hon. Inkster N.D.P. CALDWELL, Drew, Hon. Brandon East N.D.P. CERILLI, Marianne Radisson N.D.P. CHOMIAK, Dave, Hon. Kildonan N.D.P. CUMMINGS, Glen Ste. Rose P.C. DACQUA Y, Louise Seine River P.C. DERKACH, Leonard Russell P.C. DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk N.D.P. DOER, Gary, Hon. Concordia N.D.P. DRIEDGER, Myrna Charles wood P.C. DYCK, Peter Pembina P.C. ENNS, Harry Lakeside P.C. FAURSCHOU, David Portage Ia Prairie P.C. FILMON, Gary Tuxedo P.C. FRIESEN, Jean, Hon. Wolseley N.D.P. GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GILLESHAMMER, Harold Minnedosa P.C. HELWER, Edward Gimli P.C. HICKES, George Point Douglas N.D.P. JENNISSEN, Gerard Flin Flon N.D.P. KORZENIOWSKI, Bonnie St. James N.D.P. LATHLIN, Oscar, Hon. The Pas N.D.P. LAURENDEAU, Marcel St. Norbert P.C. LEMIEUX, Ron, Hon. La Verendrye N.D.P. LOEWEN, John Fort Whyte P.C. MACKINTOSH, Gord, Hon. St. Johns N.D.P. MAGUIRE, Larry Arthur-Virden P.C. MALOWA Y, Jim Elmwood N.D.P. MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows N.D.P. -

DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

Second Session – Forty-Second Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable Myrna Driedger Speaker Vol. LXXIV No. 2 - 1:30 p.m., Wednesday, November 20, 2019 ISSN 0542-5492 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Forty-Second Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation ADAMS, Danielle Thompson NDP ALTOMARE, Nello Transcona NDP ASAGWARA, Uzoma Union Station NDP BRAR, Diljeet Burrows NDP BUSHIE, Ian Keewatinook NDP CLARKE, Eileen, Hon. Agassiz PC COX, Cathy, Hon. Kildonan-River East PC CULLEN, Cliff, Hon. Spruce Woods PC DRIEDGER, Myrna, Hon. Roblin PC EICHLER, Ralph, Hon. Lakeside PC EWASKO, Wayne Lac du Bonnet PC FIELDING, Scott, Hon. Kirkfield Park PC FONTAINE, Nahanni St. Johns NDP FRIESEN, Cameron, Hon. Morden-Winkler PC GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GOERTZEN, Kelvin, Hon. Steinbach PC GORDON, Audrey Southdale PC GUENTER, Josh Borderland PC GUILLEMARD, Sarah, Hon. Fort Richmond PC HELWER, Reg, Hon. Brandon West PC ISLEIFSON, Len Brandon East PC JOHNSON, Derek Interlake-Gimli PC JOHNSTON, Scott Assiniboia PC KINEW, Wab Fort Rouge NDP LAGASSÉ, Bob Dawson Trail PC LAGIMODIERE, Alan Selkirk PC LAMONT, Dougald St. Boniface Lib. LAMOUREUX, Cindy Tyndall Park Lib. LATHLIN, Amanda The Pas-Kameesak NDP LINDSEY, Tom Flin Flon NDP MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood NDP MARCELINO, Malaya Notre Dame NDP MARTIN, Shannon McPhillips PC MOSES, Jamie St. Vital NDP MICHALESKI, Brad Dauphin PC MICKLEFIELD, Andrew Rossmere PC MORLEY-LECOMTE, Janice Seine River PC NAYLOR, Lisa Wolseley NDP NESBITT, Greg Riding Mountain PC PALLISTER, Brian, Hon. Fort Whyte PC PEDERSEN, Blaine, Hon. Midland PC PIWNIUK, Doyle Turtle Mountain PC REYES, Jon Waverley PC SALA, Adrien St. -

A Prescription in the Public Interest? Bill 207, the Medical Amendment Act

A Prescription in the Public Interest? Bill 207, The Medical Amendment Act THERESA VANDEAN DANYLUK I.1N1RODUCTION ''when there are [private members'] proposals that the government finds in the public interest, I think there is a more recent developing interest to work together and get these proposals 1 moving." Generally, the passage of Private Members' Bills ("PMB") 1 into law is a rare feat for opposition members and government backbenchers ("private members"). In the Manitoba Legislature, this statement is particularly true-since 1992, while 141 PMBs were formulated, 88 of which were printed and introduced in the House, only four subsequently became law.3 It should, however, be noted that these figures do not account for PMBs which, after being introduced by private members but not passed, are introduced and subsequently passed in whole or in part through government legislation. Interview of Hon. Gord Mackintosh, Attorney General and Government House Leader, by Theresa Danyluk (6 October 2005) in Winnipeg, Manitoba. A private members' bill is a bill presented to the House by either a government backbencher or an opposition member. There are private members' public bills; dealing with general legislation, and private members' private bills; used most commonly for the incorporation of an organization seeking powers, which cannot be granted mder The Cmporations Act, or for amendments to existing Private Acts of Incorporation. See Manitoba, Legislative Assembly, "Private Bills, Process for Passage of a Private Bill in the Legislative Assembly of Manitoban online: The Legislative Assembly of Manitoba <http://www.gov.mb.ca/legislature/bills/privatebillguidelines.html >. Manitoba, Legislative Assembly, Journals, Appendices "C" and "D" from 4Fh Sess., 35ch Leg., 1992-93-94 to Jd Sess., 38ch Leg., 2004-05. -

1 2005 05 30 Rt. Hon. Paul Martin Premier Gary Doer Prime Minister Legislative Building House of Commons Room 204, 450 Broadway

Paul E. Clifton 852 Red River Drive Howden, MB R5A 1J4 Telephone No. (204) 269-7760 Facsimile No.: (204) 275-8142 2005 05 30 Rt. Hon. Paul Martin Premier Gary Doer Prime Minister Legislative Building House of Commons Room 204, 450 Broadway Ave. Parliament Buildings Winnipeg, Manitoba Ottawa, Ontario R3C 0V8 K1A 0A6 Manitoba’s in Constitutional Crisis Mr. Prime Minister and Premier Doer I would normally open a letter to the Prime Minister of this great country and because of it being co-addressed to a Premier of a Province with the greatest respect, irrespective of political stripes, unfortunately this will not be the case in this writing. You Mr. Prime Minister and Premier will both clearly recall my February 29, 2004 letters to your respective attentions, WRT the brutalization of my many neighbours who reside in the Upper Red River Valley. This before the successful minority victory in the last federal election by you Mr. Martin, and with Mr. Doer’s directed misconduct and sheltering of critical records continuing in Manitoba. You will also clearly recall the planned “visit to Manitoba” by as yet, an unelected PM for a “non political, but important Manitoba announcement”. Mr. Martin you will be surprised that while Premier Doer hid out at the opening of the BGH expansion project in Brandon Manitoba, your Challenger jet was held from final runway clearance and back to Ottawa, because of an inbound twin engine craft from northern Manitoba. Sir, can you imagine my profound disappointment of being 20 minutes early and not 30 – 45 minutes early and back into Winnipeg? Thus not only not being personally able to ask whether “you did the right thing, while in Manitoba” in advance of your departure out. -

Wednesday, June 21, 1995

VOLUME 133 NUMBER 223 1st SESSION 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, June 21, 1995 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, June 21, 1995 The House met at 2 p.m. industry’s viability, the government chose to let the investment climate deteriorate. _______________ We must make sure that our mining sector will be able to Prayers develop in the future and continue to create thousands of jobs in Quebec and Canada instead of abroad. _______________ * * * STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS [English] [English] NATURAL RESOURCES HIRE A STUDENT WEEK Mr. George S. Rideout (Moncton, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, as the committee on natural resources requested during the examina- Mrs. Georgette Sheridan (Saskatoon—Humboldt, Lib.): tion of the Department of National Resources Act, the Minister Mr. Speaker, the Canada employment centre for students is of Natural Resources tabled this morning the fifth annual report celebrating its annual hire a student week across Canada, June to Parliament, ‘‘The State of Canada’s Forests, 1994’’. 19 to 23. Canada’s forests continue to be a major engine of economic The goal of hire a student week is to gain support from growth for Canada, particularly in certain regions of the country potential employers and to heighten awareness of the services such as my home province of New Brunswick, but they are also available through the Canada employment centre for students in essential to our environment. Saskatoon as well as in other parts of the country. The theme of this year’s report, ‘‘A Balancing Act’’, de- People will notice the hire a student buttons being worn by scribes the challenges of maintaining timber for our industry students at the events planned to celebrate this week. -

Wednesday, February 8, 1995

VOLUME 133 NUMBER 148 1st SESSION 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, February 8, 1995 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, February 8, 1995 The House met at 2 p.m. sovereignists to defend their plans because, when all is said and done, the decision is for Quebecers to make and for them alone. _______________ * * * Prayers [English] _______________ CANADIAN AIRBORNE REGIMENT STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Mr. Jack Frazer (Saanich—Gulf Islands, Ref.): Mr. Speak- er, in her Standing Order 31 statement yesterday the hon. [Translation] member for Brant attributed to me ‘‘comments denying any racism in the video depicting conduct of some members of the HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR GENERAL Canadian Airborne Regiment’’. I assume the hon. member took Mr. Guy H. Arseneault (Restigouche—Chaleur, Lib.): Mr. this statement, out of context and misrepresenting my position, Speaker, I would like to congratulate His Excellency the Right from a media report. Hon. Roméo LeBlanc, who has just been sworn in as Governor Now I consider calling someone or an organization racist to be General of Canada. Mr. LeBlanc is clearly an excellent person a very serious charge and demand factual evidence before for the job. levelling such a charge. He has worked tirelessly and unstintingly for a united and It is one thing to have my position misrepresented in the prosperous Canada. In his speech this morning, Mr. LeBlanc media but quite another to have it misrepresented in the official expressed his love for Canada. As he said, it is up to us to build records of this House of Commons. -

Wednesday, April 24, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 032 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, April 24, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1883 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, April 24, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [English] _______________ LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA Prayers Mr. Ken Epp (Elk Island, Ref.): Mr. Speaker, voters need accurate information to make wise decisions at election time. With _______________ one vote they are asked to choose their member of Parliament, select the government for the term, indirectly choose the Prime The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now Minister and give their approval to a complete all or nothing list of sing O Canada, which will be led by the hon. member for agenda items. Vancouver East. During an election campaign it is not acceptable to say that the [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] GST will be axed with pledges to resign if it is not, to write in small print that it will be harmonized, but to keep it and hide it once the _____________________________________________ election has been won. It is not acceptable to promise more free votes if all this means is that the status quo of free votes on private members’ bills will be maintained. It is not acceptable to say that STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS MPs will be given more authority to represent their constituents if it means nothing and that MPs will still be whipped into submis- [English] sion by threats and actions of expulsion. -

Thirty-Eighth Legislature

Second Session - Thirty-Ninth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable George Hickes Speaker Vol. LX No. 11A – 10 a.m., Tuesday, December 4, 2007 ISSN 0542-5492 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Ninth Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation ALLAN, Nancy, Hon. St. Vital N.D.P. ALTEMEYER, Rob Wolseley N.D.P. ASHTON, Steve, Hon. Thompson N.D.P. BJORNSON, Peter, Hon. Gimli N.D.P. BLADY, Sharon Kirkfield Park N.D.P. BOROTSIK, Rick Brandon West P.C. BRAUN, Erna Rossmere N.D.P. BRICK, Marilyn St. Norbert N.D.P. BRIESE, Stuart Ste. Rose P.C. CALDWELL, Drew Brandon East N.D.P. CHOMIAK, Dave, Hon. Kildonan N.D.P. CULLEN, Cliff Turtle Mountain P.C. DERKACH, Leonard Russell P.C. DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk N.D.P. DOER, Gary, Hon. Concordia N.D.P. DRIEDGER, Myrna Charleswood P.C. DYCK, Peter Pembina P.C. EICHLER, Ralph Lakeside P.C. FAURSCHOU, David Portage la Prairie P.C. GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GOERTZEN, Kelvin Steinbach P.C. GRAYDON, Cliff Emerson P.C. HAWRANIK, Gerald Lac du Bonnet P.C. HICKES, George, Hon. Point Douglas N.D.P. HOWARD, Jennifer Fort Rouge N.D.P. IRVIN-ROSS, Kerri, Hon. Fort Garry N.D.P. JENNISSEN, Gerard Flin Flon N.D.P. JHA, Bidhu Radisson N.D.P. KORZENIOWSKI, Bonnie St. James N.D.P. LAMOUREUX, Kevin Inkster Lib. LATHLIN, Oscar, Hon. The Pas N.D.P. LEMIEUX, Ron, Hon. La Verendrye N.D.P. MACKINTOSH, Gord, Hon. -

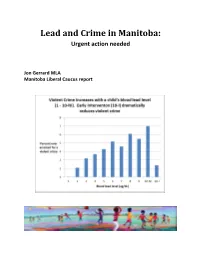

Lead and Crime in Manitoba: Urgent Action Needed

Lead and Crime in Manitoba: Urgent action needed Jon Gerrard MLA Manitoba Liberal Caucus report “Lead poisoning is the most significant and prevalent disease of environmental origin in US children” -Silbergeld 1997 Lead exposure contributing to violence and crime is, “a public health crisis with serious social justice implications” -Emer et al 2020 “mounting evidence [supports] that preschool lead exposure affects the risk of criminal behavior later in life. … especially affects juvenile offending and related trends in index crime (mainly property crime rates and burglary)… Violent crime trends and shifts to higher adult arrest rates suggest blood lead also affects violent and repeat offending.” -Nevin 2007 “The hypothesis that murder rates are especially affected by severe lead poisoning is consistent with international and racial contrasts and a cross-sectional analysis of average 1985-1994 USA city murder rates.” -Nevin 2007 “1941-1975 gasoline lead use explained 90% of the 1964-1998 variation in USA violent crime.” - Economist Rick Nevin, from a study published in 2000, and reported by CTV news March 7, 2013 “We can either attack crime at its root by getting rid of the remaining lead in our environment, or we can continue our current policy of waiting 20 years and then locking up all the lead-poisoned kids who have turned into criminals.” -Drum 2016 “Cleaning up the rest of the lead that remains in our environment could turn out to be the cheapest, most effective crime prevention tool we have.” -Drum 2016 “Children found to have a blood lead level higher than 5 ug/dL (0.24 umol/L) should be investigated thoroughly and any identified exposure sources should be mitigated as soon as possible.” - Canadian Pediatric Society 2019 “The impact of lead is intergenerational. -

January 11, 2021

Minutes Provincial Executive Meeting Monday, January 11, 2021 Leadership, advocacy and service for Manitoba’s public school boards Via Zoom Video‐Conference 9:00 a.m. PRESENT: Alan Campbell President Sandy Nemeth Vice‐President Floyd Martens Vice‐President Sherilyn Bambridge Director Region #1 Leah Klassen Director Region #2 Lena Kublick Director Region #3 Vaughn Wadelius Director Region #4 Sandra Lethbridge Director Region #5 Julie Fisher Director Region #5 Chris Broughton Director Region #6 Josh Watt Executive Director Janis Arnold Acting Director, Education and Communication Services Robyn Winters Chief Financial Officer Andrea Kehler Executive Assistant REGRETS: Morgan Whiteway Interim Director, Labour Relations and Human Resource Services Alan Campbell, President, welcomed everyone and called the meeting to order at 9:00 a.m. 1.1 LAND AND TREAY AKNOWLEDGMENT Before we begin today’s meetings, I would like to acknowledge that the lands on which we are gathering are the lands of the St. Peter’s or Selkirk Treaty and of Numbered Treaties 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, territories of the Anishinaabe Cree, Dene, Dakota and Oji‐Cree peoples, and Traditional homeland of the Métis nation. We acknowledge the wrongs of the past and stand committed to building positive relationships rooted in a spirit of genuine reconciliation. 1.2 ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA Add: to 5.3 – Bill 45 Fisher/Wadelius THAT the agenda be adopted as amended. Carried Minutes, Provincial Executive Meeting, January 11, 2021, cont’d… 2 1.3 ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES Klassen/Bambridge THAT the minutes of the Provincial Executive meeting December 14, 2020 be approved as circulated. -

ALL the WAY HOME ENDING 40+ YEARS of FORCED Homelessness in Winnipeg

ALL THE WAY HOME ENDING 40+ YEARS OF FORCED HomelessNESS in Winnipeg Manitoba Liberal Caucus February 7, 2021 1 This report was prepared by Dr. Jon Gerrard, MLA for River Heights, with help from homelessness activist Nancy Chippendale; with guidance, input and oversight from Dougald Lamont, Manitoba Liberal Leader and MLA for St. Boniface. “It is said that a society should be judged by how we treat its most vulnerable people, and on that score, the Manitoba Government’s behaviour has been appalling. As a society, we have everything to gain and nothing to lose by treating people who are homeless with dignity.” - Manitoba Liberal Leader Dougald Lamont, MLA for St. Boniface, Dec 30 2020 More Than Facts and Figures: Behind every Number is a Human Life There is a saying that poverty is the greatest censor. People who experience poverty, or who turn to social assistance, may feel ashamed. They are shamed, blamed and judged because their lot in life is blamed on their decisions and choices, and not on the decisions of policy makers that exclude entire populations from the basic necessities of life - food, water, medicine, shelter, clothing. As the saying goes, “There but for the Grace of God go I” - none of us choose the life we are born into. Especially when it comes to Indigenous people, governments have had policies of deliberate exclusion and forced poverty. Doors to opportunity were and are nailed shut. This is not fate: it is choice – choice by governments and policymakers whether to put people to work, or to invest in housing, education, and mental health. -

Legislative Reports

Legislative Reports and efficiencies in government position by the end of the first quar- departments; ter. • elimination of duplication and Speaker’s Ruling overlap; • redirection of realized savings to On April 2, Opposition House front-line care and services; Leader Kelly Lamrock (MLA for • a balanced budget for 2004-2005 Fredericton-Fort Nashwaak), in ris- with a modest reduction in net ing on a question of privilege cited debt of $2.4 million. media reports that the government had begun to reduce the number of The Minister noted that the bud- positions in the civil service, as out- New Brunswick get will be balanced over the lined in the government’s budget. four-year period 2000-2001 to The Member submitted that by tak- he first session of the Fifty-fifth 2003-2004 with an anticipated cu- ing this action, prior to the budget TLegislature which adjourned mulative surplus of $161.8 million, being considered and approved by December 19, 2003, resumed on in accordance with balanced budget the House, the government has ei- March30whenFinanceMinister legislation – the first time that the ther breached the rule of anticipa- Jeannot Volpé (MLA for balanced budget legislation has tion, or had obstructed or impeded Madawaska-les-Lacs) delivered the been met over a four-year cycle. the House in the performance of its 2004-2005 budget address. The In his response to the 2004-2005 functions, which had resulted in an Minister noted that the first budget Budget, Opposition Leader and Fi- offence against the authority or dig- of this Legislature was sending a nance Critic Shawn Graham (MLA nity of the House.