Kepler-36: a Pair of Planets with Neighboring Orbits and Dissimilar Densities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Precision Photometry of Transiting Exoplanets

McNair Scholars Research Journal Volume 3 Article 3 2016 High Precision Photometry of Transiting Exoplanets Maurice Wilson Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Jason Eastman Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics John Johnson Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation Wilson, Maurice; Eastman, Jason; and Johnson, John (2016) "High Precision Photometry of Transiting Exoplanets," McNair Scholars Research Journal: Vol. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/mcnair/vol3/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McNair Scholars Research Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wilson et al.: High Precision Photometry of Transiting Exoplanets High Precision Photometry of Transiting Exoplanets Maurice Wilson1,2, Jason Eastman2, and John Johnson2 1Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University 2Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics In order to increase the rate of finding, confirming, and characterizing Earth-like exoplanets, the MINiature Exoplanet Radial Velocity Array (MINERVA) was recently built with the purpose of obtaining the spectroscopic and photometric precision necessary for these tasks. Achieving the satisfactory photometric precision is the primary focus of this work. This is done with the four telescopes of MINERVA and the defocusing technique. The satisfactory photometric precision derives from the defocusing technique. The use of MINERVA’s four telescopes benefits the relative photometry that must be conducted. Typically, it is difficult to find satisfactory comparison stars within a telescope’s field of view when the primary target is very bright. -

Characterizing Two Solar-Type Kepler Subgiants with Asteroseismology: Kic 10920273 and Kic 11395018

The Astrophysical Journal, 763:49 (10pp), 2013 January 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/763/1/49 C 2013. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. CHARACTERIZING TWO SOLAR-TYPE KEPLER SUBGIANTS WITH ASTEROSEISMOLOGY: KIC 10920273 AND KIC 11395018 G. Doganˇ 1,2,3, T. S. Metcalfe1,3,4, S. Deheuvels3,5,M.P.DiMauro6, P. Eggenberger7, O. L. Creevey8,9,10, M. J. P. F. G. Monteiro11, M. Pinsonneault3,12, A. Frasca13, C. Karoff2, S. Mathur1,S.G.Sousa11,I.M.Brandao˜ 11, T. L. Campante11,14, R. Handberg2, A. O. Thygesen2,15, K. Biazzo16,H.Bruntt2, E. Niemczura17, T. R. Bedding18, W. J. Chaplin3,14, J. Christensen-Dalsgaard2,3,R.A.Garc´ıa3,19, J. Molenda-Zakowicz˙ 17, D. Stello18, J. L. Van Saders3,12, H. Kjeldsen2, M. Still20, S. E. Thompson21, and J. Van Cleve21 1 High Altitude Observatory, National Center for Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 3000, Boulder, CO 80307, USA; [email protected] 2 Stellar Astrophysics Centre, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 120, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 3 Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, Kohn Hall, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA 4 Space Science Institute, Boulder, CO 80301, USA 5 Department of Astronomy, Yale University, P.O. Box 208101, New Haven, CT 06520-8101, USA 6 INAF-IAPS, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Via del Fosso del Cavaliere 100, I-00133 Roma, Italy 7 Geneva Observatory, University of Geneva, Maillettes 51, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 8 Universite´ de Nice, Laboratoire Cassiopee,´ CNRS UMR 6202, Observatoire de la Coteˆ d’Azur, BP 4229, F-06304 Nice Cedex 4, France 9 IAC Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Canarias, C/V´ıa Lactea´ s/n, E-38200 Tenerife, Spain 10 Universidad de La Laguna, Avda. -

Practical Observational Astronomy Photometry

Practical Observational Astronomy Lecture 5 Photometry Wojtek Pych Warszawa, October 2019 History ● Hipparchos 190 – 120 B.C. visible stars divided into 6 magnitudes ● John Hershel 1792- 1871 → Norman Robert Pogson A.D. 1829 - 1891 I m I 1 =100 m1−m2=−2.5 log( ) I m+5 I 2 Visual Observations ●Argelander method ●Cuneiform photometer ●Polarimetric photometer Visual Observations Copyright AAVSO The American Association of Variable Star Observers Photographic Plates Blink comparator Scanning Micro-Photodensitometer Photographic plates Liller, Martha H.; 1978IBVS.1527....1L Photoelectric Photometer ● Photomultiplier tubes – Single star measurement – Individual photons Photoelectric Photometer ● 1953 - Harold Lester Johnson - UBV system – telescope with aluminium covered mirrors, – detector is photomultiplier 1P21, – for V Corning 3384 filter is used, – for B Corning 5030 + Schott CG13 filters are used, – for U Corning 9863 filter is used. – Telescope at altitude of >2000 meters to allow the detection of sufficent amount of UV light. UBV System Extensions: R,I ● William Wilson Morgan ● Kron-Cousins CCD Types of photometry ● Aperture ● Profile ● Image subtraction Aperture Photometry Aperture Photometry Profile Photometry Profile Photometry DAOphot ● Find stars ● Aperture photometry ● Point Spread Function ● Profile photometry Image Subtraction Image Subtraction ● Construct a template image – Select a number of best quality images – Register all images into a selected astrometric position ● Find common stars ● Calculate astrometric transformation -

“Astrometry/Photometry of Solar System Objects After Gaia”

ISSN 1621-3823 ISBN 2-910015-77-7 NOTES SCIENTIFIQUES ET TECHNIQUES DE L’INSTITUT DE MÉCANIQUE CÉLESTE S106 Proceedings of the Workshop and colloquium held at the CIAS (Meudon) on October 14-18, 2015 “Astrometry/photometry of Solar System objects after Gaia” Institut de mécanique céleste et de calcul des éphémérides CNRS UMR 8028 / Observatoire de Paris 77, avenue Denfert-Rochereau 75014 Paris Mars 2017 Dépôt légal : Mars 2017 ISBN 2-910015-77-7 Foreword The modeling of the dynamics of the solar system needs astrometric observations made on a large interval of time to validate the scenarios of evolution of the system and to be able to provide ephemerides extrapolable in the next future. That is why observations are made regularly for most of the objects of the solar system. The arrival of the Gaia reference star catalogue will allow us to make astrometric reductions of observations with an increased accuracy thanks to new positions of stars and a more accurate proper motion. The challenge consists in increasing the astrometric accuracy of the reduction process. More, we should think about our campaigns of observations: due to this increased accuracy, for which objects, ground based observations will be necessary, completing space probes data? Which telescopes and targets for next astrometric observations? The workshop held in Meudon tried to answer these questions. Plans for the future have been exposed, results on former campaigns such as Phemu15 campaign, have been provided and amateur astronomers have been asked for continuing their participation to new observing campaigns of selected objects taking into account the new possibilities offered by the Gaia reference star catalogue. -

69-22,173 MARKOWITZ, Allan Henry, 1941- a STUDY of STARS

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly u received 6 9 -2 2 ,1 7 3 MARKOWITZ, Allan Henry, 1941- A STUDY OF STARS EXHIBITING COM POSITE SPECTRA. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 A stron om y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan A STUDY OF STARS EXHIBITING COMPOSITE SPECTRA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Allan Henry Markowitz, A.B., M.Sc. ******** The Ohio S ta te U n iv e rsity 1969 Approved by UjiIjl- A dviser Department of Astronomy ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a sincere pleasure to thank my adviser, Professor Arne Slettebak, who originally suggested this problem and whose advice and encouragement were indispensable throughout the course of the research. I am also greatly indebted to Professor Philip Keenan for help in classifying certain late-type spectra and to Professor Terry Roark for instructing me in the operation of the Perkins Observatory telescope, I owe a special debt of gratitude to Dr. Carlos Jaschek of the La Plata Observatory for his inspiration, advice, and encourage ment. The Lowell Observatory was generous in providing extra telescope time when the need arose. I wish to particularly thank Dr. John Hall for this and for his interest. I also gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Perkins Observatory staff. To my wife, Joan, I owe my profound thanks for her devotion and support during the seemingly unending tenure as a student. I am deeply grateful to my mother for her eternal confidence and to my in-laws for their encouragement. -

Magnetism, Dynamo Action and the Solar-Stellar Connection

Living Rev. Sol. Phys. (2017) 14:4 DOI 10.1007/s41116-017-0007-8 REVIEW ARTICLE Magnetism, dynamo action and the solar-stellar connection Allan Sacha Brun1 · Matthew K. Browning2 Received: 23 August 2016 / Accepted: 28 July 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract The Sun and other stars are magnetic: magnetism pervades their interiors and affects their evolution in a variety of ways. In the Sun, both the fields themselves and their influence on other phenomena can be uncovered in exquisite detail, but these observations sample only a moment in a single star’s life. By turning to observa- tions of other stars, and to theory and simulation, we may infer other aspects of the magnetism—e.g., its dependence on stellar age, mass, or rotation rate—that would be invisible from close study of the Sun alone. Here, we review observations and theory of magnetism in the Sun and other stars, with a partial focus on the “Solar-stellar connec- tion”: i.e., ways in which studies of other stars have influenced our understanding of the Sun and vice versa. We briefly review techniques by which magnetic fields can be measured (or their presence otherwise inferred) in stars, and then highlight some key observational findings uncovered by such measurements, focusing (in many cases) on those that offer particularly direct constraints on theories of how the fields are built and maintained. We turn then to a discussion of how the fields arise in different objects: first, we summarize some essential elements of convection and dynamo theory, includ- ing a very brief discussion of mean-field theory and related concepts. -

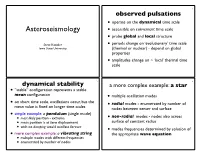

Asteroseismology Notes

2 observed pulsations • operate on the dynamical time scale Asteroseismology • accessible on convenient time scale • probe global and local structure Steve Kawaler • periods change on ‘evolutionary’ time scale Iowa State University (thermal or nuclear) - depend on global properties • amplitudes change on ~ ‘local’ thermal time scale 3 4 dynamical stability a more complex example: a star • “stable” configuration represents a stable mean configuration • multiple oscillation modes • on short time scale, oscillations occur, but the • radial modes - enumerated by number of mean value is fixed on longer time scales nodes between center and surface • simple example: a pendulum (single mode) • most likely position - extrema • non-radial modes - nodes also across • mean position is at zero displacement surface of constant radius with no damping would oscillate forever • • modes frequencies determined by solution of • more complex example: a vibrating string the appropriate wave equation • multiple modes with different frequencies • enumerated by number of nodes 5 6 stability, damping, and driving Okay, start your engines... • PG 1159: light curve • zero energy change: what kind of star might this be? constant amplitude oscillation • • what kind of star can this not possibly be? • energy loss via pulsation: • what about the amplitude over the run? oscillation amplitude drops with time • PG 1336 light curve • if net energy input: • huh? what time scale(s) are involved amplitude increases with time • what kind of star (or stars)? (if properly phased) -

Atmosphere Observation by the Method of LED Sun Photometry

Atmosphere Observation by the Method of LED Sun Photometry A Senior Project presented to the Faculty of the Physics Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Bachelor of Science by Gregory Garza April 2013 1 Introduction The focus of this project is centered on the subject of sun photometry. The goal of the experiment was to use a simple self constructed sun photometer to observe how attenuation coefficients change over longer periods of time as well as the determination of the solar extraterrestrial constants for particular wavelengths of light. This was achieved by measuring changes in sun radiance at a particular location for a few hours a day and then use of the Langley extrapolation method on the resulting sun radiance data set. Sun photometry itself is generally involved in the practice of measuring atmospheric aerosols and water vapor. Roughly a century ago, the Smithsonian Institutes Astrophysical Observatory developed a method of measuring solar radiance using spectrometers; however, these were not usable in a simple hand-held setting. In the 1950’s Frederick Volz developed the first hand-held sun photometer, which he improved until coming to the use of silicon photodiodes to produce a photocurrent. These early stages of the development of sun photometry began with the use of silicon photodiodes in conjunction with light filters to measure particular wavelengths of sunlight. However, this method of sun photometry came with cost issues as well as unreliability resulting from degradation and wear on photodiodes. A more cost effective method was devised by amateur scientist Forrest Mims in 1989 that incorporated the use of light emitting diodes, or LEDs, that are responsive only to the light wavelength that they emit. -

Chapter 4 Introduction to Stellar Photometry

Chapter 4 Introduction to stellar photometry Goal-of-the-Day Understand the concept of stellar photometry and how it can be measured from astro- nomical observations. 4.1 Essential preparation Exercise 4.1 (a) Have a look at www.astro.keele.ac.uk/astrolab/results/week03/week03.pdf. 4.2 Fluxes and magnitudes Photometry is a technique in astronomy concerned with measuring the brightness of an astronomical object’s electromagnetic radiation. This brightness of a star is given by the flux F : the photon energy which passes through a unit of area within a unit of time. The flux density, Fν or Fλ, is the flux per unit of frequency or per unit of wavelength, respectively: these are related to each other by: Fνdν = Fλdλ (4.1) | | | | Whilst the total light output from a star — the bolometric luminosity — is linked to the flux, measurements of a star’s brightness are usually obtained within a limited frequency or wavelength range (the photometric band) and are therefore more directly linked to the flux density. Because the measured flux densities of stars are often weak, especially at infrared and radio wavelengths where the photons are not very energetic, the flux density is sometimes expressed in Jansky, where 1 Jy = 10−26 W m−2 Hz−1. However, it is still very common to express the brightness of a star by the ancient clas- sification of magnitude. Around 120 BC, the Greek astronomer Hipparcos ordered stars in six classes, depending on the moment at which these stars became first visible during evening twilight: the brightest stars were of the first class, and the faintest stars were of the sixth class. -

Planet Hunters1 (Fischer Et Al

draft version May 31, 2012 Planet Hunters: Assessing the Kepler Inventory of Short Period Planets Megan E. Schwamb1,2,3,Chris J. Lintott4,5, Debra A. Fischer6, Matthew J. Giguere6, Stuart Lynn5,4, Arfon M. Smith5,4, John M. Brewer6, Michael Parrish5, Kevin Schawinski2,3,7, and Robert J. Simpson4 [email protected] ABSTRACT We present the results from a search of data from the first 33.5 days of the Kepler science mission (Quarter 1) for exoplanet transits by the Planet Hunters citizen science project. Planet Hunters enlists members of the general public to visually identify tran- sits in the publicly released Kepler light curves via the World Wide Web. Over 24,000 volunteers reviewed the Kepler Quarter 1 data set. We examine the abundance of ≥ 2 R⊕ planets on short period (< 15 days) orbits based on Planet Hunters detections. We present these results along with an analysis of the detection efficiency of human classifiers to identify planetary transits including a comparison to the Kepler inventory of planet candidates. Although performance drops rapidly for smaller radii, ≥ 4 R⊕ Planet Hunters ≥ 85% efficient at identifying transit signals for planets with periods less than 15 days for the Kepler sample of target stars. Our high efficiency rate for simulated transits along with recovery of the majority of Kepler ≥4R⊕ planets suggest suggests the Kepler inventory of ≥4 R⊕ short period planets is nearly complete. Subject headings: Planets and satellites: detection-Planets and satellites: general 1. Introduction In the past nearly two decades, there has been an explosion in the number of known planets arXiv:1205.6769v1 [astro-ph.EP] 30 May 2012 orbiting stars beyond our own solar system, with over 700 extrasolar planets (exoplanets) known 1Yale Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Yale University,P.O. -

20 Jun 2012 Kepler-36: a Pair of Planets with Neighboring Orbits

Kepler-36: A Pair of Planets with Neighboring Orbits and Dissimilar Densities Joshua A. Carter1+∗, Eric Agol2+∗, William J. Chaplin3, Sarbani Basu4, Timothy R. Bedding5, Lars A. Buchhave6, Jørgen Christensen-Dalsgaard7, Katherine M. Deck8, Yvonne Elsworth3, Daniel C. Fabrycky9, Eric B. Ford10, Jonathan J. Fortney11, Steven J. Hale3, Rasmus Handberg7, Saskia Hekker12, Matthew J. Holman13, Daniel Huber14, Christopher Karoff7, Steven D. Kawaler15, Hans Kjeldsen7, Jack J. Lissauer14, Eric D. Lopez11, Mikkel N. Lund7, Mia Lundkvist7, Travis S. Metcalfe16, Andrea Miglio3, Leslie A. Rogers8, Dennis Stello5, William J. Borucki14, Steve Bryson14, Jessie L. Christiansen17, William D. Cochran18, John C. Geary13, Ronald L. Gilliland19, Michael R. Haas14, Jennifer Hall20, Andrew W. Howard21, Jon M. Jenkins17, Todd Klaus20, David G. Koch14, David W. Latham13, Phillip J. MacQueen18, Dimitar Sasselov13, Jason H. Steffen22, Joseph D. Twicken17, Joshua N. Winn8 1Hubble Fellow, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 2Department of Astronomy, Box 351580, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA arXiv:1206.4718v1 [astro-ph.EP] 20 Jun 2012 3School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, B15 2TT, UK 4Department and Astronomy, Yale University, New Haven, CT, 06520, USA 5Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen University, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 6Centre for Star and Planet Formation, Natural History -

Development of a Stellar Model-Fitting Pipeline for Asteroseismic Data from the TESS Mission

Development of a Stellar Model-Fitting Pipeline for Asteroseismic Data from the TESS Mission PI: Travis Metcalfe / Co-I: Rich Townsend Collaborators: David Guenther, Dennis Stello The launch of NASA’s Kepler space telescope in 2009 revolutionized the quality and quantity of observational data available for asteroseismic analysis. Prior to the Kepler mission, solar-like oscillations were extremely difficult to observe, and data only existed for a handful of the brightest stars in the sky. With the necessity of studying one star at a time, the traditional approach to extracting the physical properties of the star from the observations was an uncomfortably subjective process. A variety of experts could use similar tools but come up with significantly different answers. Not only did this subjectivity have the potential to undermine the credibility of the technique, it also hindered the compilation of a uniform sample that could be used to draw broader physical conclusions from the ensemble of results. During a previous award from NASA, we addressed these issues by developing an automated and objective stellar model-fitting pipeline for Kepler data, and making it available through the Asteroseismic Modeling Portal (AMP). This community modeling tool has allowed us to derive reliable asteroseismic radii, masses and ages for large samples of stars (Metcalfe et al., 2014), but the most recent observations are so precise that we are now limited by systematic uncertainties associated with our stellar models. With a huge archive of Kepler data available for model validation, and the next planet-hunting satellite already approved for an expected launch in 2017, now is the time to incorporate what we have learned into the next generation of AMP.