Legislative Council Panel on Public Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electoral Affairs Commission Report on the 2005 Chief Executive Election

ABBREVIATIONS APROs Assistant Presiding Officers AROs Assistant Returning Officers CAB Constitutional Affairs Bureau Cap Chapter of the Laws of Hong Kong CAS Civil Aid Service CCC Central Co-ordination Centre CE Chief Executive CE Election (Amendment) Chief Executive Election (Amendment) (Term of (Term of Office of the CE) Office of the Chief Executive) Ordinance Ord CEEO Chief Executive Election Ordinance (Cap 569) CEO Chief Electoral Officer CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CSB Civil Service Bureau CSTDI Civil Service Training and Development Institute D of J Department of Justice DC, DCs District Council, District Councils DPRO, DPROs Deputy Presiding Officer, Deputy Presiding Officers EA, EAs Election Advertisement, Election Advertisements EAC or the Commission Electoral Affairs Commission EAC (EP) (EC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) (Election Committee) Regulation EAC (R) (FCSEC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Registration) (Electors for Legislative Council Functional Constituencies) (Voters for Election Committee Subsectors) (Members of Election Committee) Regulation EACO Electoral Affairs Commission Ordinance (Cap 541) EC Election Committee ECICO Elections (Corrupt and Illegal Conduct) Ordinance (Cap 554) ECSS Election Committee Subsector EP (CEE) Reg Electoral Procedure (Chief Executive Election) Regulation ERO Electoral Registration Officer FC, FCs Functional Constituency, Functional Constituencies FR final register HAD Home Affairs Department HITEC Hongkong International Trade -

Annual Report 2018-2019

SIR DAVID TRENCH FUND FOR RECREATION ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 SirDavid TrenchFundFor Recreation CONTENTS Page Members of Sir David Trench Fund Committee 2 Members of Investment Advisory Committee 2 Board of Directors of Hong Kong Sports Institute Limited 3 Members of Elite Training and Athletes Affairs Committee 3 Members of Sub-committee on the Arts Development Fund under the Advisory 4 Committee On Arts Development Trustee’s Report 5 Report of the Secretary for Home Affairs 9 Report of the Director of Audit 12 Balance Sheet 15 Income and Expenditure Account 17 Statement of Changes in Equity 18 Statement of Cash Flows 20 Notes to the Financial Statements 21 Schedule 1 Statement of Approved Grants 42 Schedule 2 Summary of Approved Grants and Outstanding Commitments 51 Charts* Main Fund - Approved Grants by Types of Organisation for the Year Ended 31 March 2019 52 - Approved Grants for the Years 2014-15 to 2018-19 53 Sports Aid Foundation Fund - Approved Grants for the Years 2014-15 to 2018-19 54 Arts Development Fund - Approved Grants for the Years 2014-15 to 2018-19 55 Hong Kong Athletes Fund - Approved Grants for the Years 2014-15 to 2018-19 56 Arts and Sport Development Fund - Approved Grants by Types of Activity for the Year Ended 31 March 2019 57 - Approved Grants for the Years 2014-15 to 2018-19 58 Schedule 3 Statement of Investments 59 *Except the Sports Aid for the Disabled Fund which did not have any grant approved in the years 2014-15 to 2018-19. 1 Sir David TrenchFund For Recreation MEMBERS OF COMMITTEES 2018-2019 SIR DAVID TRENCH FUND COMMITTEE Chairman : Mr CHENG Ka-ho, MH, JP (w.e.f. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Extension of the Service of Civil Servants

Public Service Research Office Legislative Council Secretariat ISSH36/18-19 Extension of the service of civil servants Figure 1 – Hong Kong labour force projection, Highlights 2017-2066 In the face of an ageing population and a shrinking ('000) labour force (Figure 1), the Government, being the 3 700 largest employer in Hong Kong, announced in 2015 3 600 a new retirement age for new recruits employed 3 500 3 400 on or after 1 June 2015 at 65 for civilian staff and 3 300 60 for disciplined services staff. Serving civil servants joining the Government between 3 200 1 June 2000 and 31 May 2015 are also allowed to 3 100 choose to retire at 65 (for civilian grades) or 60 (for 3 000 2017 2024 2031 2038 2045 2052 2059 2066 disciplined services grades) on a voluntary basis. As at 16 February 2019, about 16 000 or 29% of some 56 000 eligible civil servants had chosen to Figure 2 – Breakdown of full-time PRSC staff by retire at a later date. B/Ds, position as at end-June 2018 In addition to raising the retirement age, a number (a) The top seven B/Ds by the number of applications of flexible measures have also been introduced to received extend the service of civil servants after their Bureau/Department/Office Number of Number of retirements. These include (a) the Post-retirement applications full-time Service Contract ("PRSC") Scheme; (b) further involved PRSC staff employment for a longer duration of up to Working Family and Student 878 21 five years; and (c) the final extension of service up Financial Assistance Agency Water Supplies Department 813 227 to 120 days. -

Guidance Notes for the Management of Indoor Air Quality in Offices and Public Places

Guidance Notes for the Management of Indoor Air Quality in Offices and Public Places The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Indoor Air Quality Management Group January 2019 FOREWORD In modern city life, the quality of air in the indoor environment has a significant impact on human health and comfort. People spend most of their time at homes, offices and other indoor environment. Poor indoor air quality (IAQ) can lead to discomfort, ill health, and, in the workplace, lead to absenteeism and lower productivity. Good indoor air quality safeguards the health of the building occupants and contributes to their comfort and well-being. Indoor air pollution has received little attention in the past compared with air pollution in the outdoor environment. It has now become a matter of increasing public concern, prompted partly by the emergence of new indoor air pollutants, by the isolation of the indoor environment from the natural outdoor environment in well-sealed buildings, and by the investigation of so-called Sick Building Syndrome. The World Health Organization (WHO) also recognises that biological and chemical indoor air pollution as public health risks. The health effects of individual indoor air pollutants are studied extensively. For example, the health impact of formaldehyde is well documented. Two guidelines were published by WHO in 2009 and 2010 respectively on mould and dampness, and selected indoor air pollutants. On the other hand, the health effects of a combination of indoor air pollutants are much less well understood and more difficult to tackle. This is due to the shortage of reliable data on the effects on human health; difficulties in accurately measuring air pollutants at low levels; potential interactions between pollutants; and wide variations in the degree to which building occupants are susceptible to air pollutants. -

Hong Kong 2006

National Integrity Systems Transparency International Integrity Study Report Hong Kong 2006 National Integrity System Country Studies 2006 Lead Author Jean Yves Le Corre, MSc. in Management and Sloan Fellow from London Business School (U.K.), is the Founder and Managing Director of InterauditAsia Co. Ltd., an independent consultancy incorporated in Hong Kong specialising in internal control, audit review methodologies and governance in the Asia Pacific region (www.bestofmanagement.com). The National Integrity Systems TI Report of Hong Kong is part of a 2006 series of National Integrity System Country Studies of East and Southeast Asia made possible with funding from: Sovereign Global Development The Starr Foundation The Council for the Korean Pact on Anti-Corruption and Transparency United Kingdom Department for International Development All material contained in this report was believed to be accurate as of 2006. Every effort has been made to verify the information contained herein, including allegations. Nevertheless, Transparency International does not accept responsibility for the consequences of the use of this information for other purposes or in other contexts. © 2006 Transparency International Transparency International Secretariat Alt Moabit 96 10559 Berlin Germany http://www.transparency.org Hong Kong 2 National Integrity System Country Studies 2006 Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following professionals for their contribution; the report could not have been written without their input: Anthony Cheung, Professor, Department of Public and Social Administration, City University of Hong Kong David O’Rear, Chief Economist, Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce Richard Welford, Professor, University of Hong Kong David M. Webb, Editor, webb-site.com T.J. -

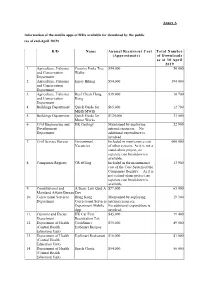

Information of the Mobile Apps of B/Ds Available for Download by the Public (As of End-April 2019)

Annex A Information of the mobile apps of B/Ds available for download by the public (as of end-April 2019) B/D Name Annual Recurrent Cost Total Number (Approximate) of Downloads as at 30 April 2019 1. Agriculture, Fisheries Country Parks Tree $54,000 50 000 and Conservation Walks Department 2. Agriculture, Fisheries Enjoy Hiking $54,000 394 000 and Conservation Department 3. Agriculture, Fisheries Reef Check Hong $39,000 10 700 and Conservation Kong Department 4. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $65,000 12 700 MBIS/MWIS 5. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $120,000 33 000 Minor Works 6. Civil Engineering and HK Geology Maintained by deploying 22 900 Development internal resources. No Department additional expenditure is involved. 7. Civil Service Bureau Government Included in maintenance cost 600 000 Vacancies of other systems. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 8. Companies Registry CR eFiling Included in the maintenance 13 900 cost of the Core System of the Companies Registry. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 9. Constitutional and A Basic Law Quiz A $77,000 65 000 Mainland Affairs Bureau Day 10. Correctional Services Hong Kong Maintained by deploying 19 300 Department Correctional Services internal resources. Department Mobile No additional expenditure is App involved. 11. Customs and Excise HK Car First $45,000 19 400 Department Registration Tax 12. Department of Health CookSmart: $35,000 49 000 (Central Health EatSmart Recipes Education Unit) 13. Department of Health EatSmart Restaurant $16,000 41 000 (Central Health Education Unit) 14. -

Explanatory Materials to the Code of Practice on Wind Effects in Hong Kong 2004

Explanatory Materials to the Code of Practice on Wind Effects in Hong Kong 2004 © The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region First published : December 2004 Prepared by: Buildings Department, 12/F-18/F Pioneer Centre, 750 Nathan Road, Mongkok, Kowloon, Hong Kong. This publication can be purchased by writing to: Publications Sales Section, Information Services Department, Room 402, 4th Floor, Murray Building, Garden Road, Central, Hong Kong. Fax: (852) 25237195 Or: Calling the Publications Sales Section of Information Services Department (ISD) at (852)25371910 Visiting the online HK SAR Government Bookstore at http://bookstore.esdlife.com Downloading the order form from the ISD website at http://www.isd.gov.hk and submitting the order online or by fax to (852) 25237195 Place order with ISD by e-mail at [email protected] Foreword The Explanatory Materials give a summary of the background information and considerations reviewed by the code drafting committee during the preparing of the Code of Practice on Wind Effects in Hong Kong 2004, which will be referred to as ‘the Code’ in this document. As the Code aims to retain the essence of a simple format of its predecessor for ease of application, the Explanatory Materials was set out to accomplish the Code by explaining in depth the major changes in the Code and to address on situations where the application of the Code may require special attention. The Explanatory Materials is a technical publication and should not be taken as a part of the Code. (i) Acknowledgment The compilation of the Explanatory Materials to the Code of Practice on Wind Effects Hong Kong 2004 owes a great deal to Dr. -

Civil Servants' Guide to Good Practices

CCivil Servants' Guide to Good Practices Civil Service Bureau 2005 CONTENTS Foreword 3 1. Core Values of the Civil Service 5 2. Attendance and Diligence at Work 7 3. Supervisory Responsibilities 9 4. Probity 11 5. Acceptance of Advantages and Entertainment 13 6. Conflict of Interest 15 7. Declaration of Investments 17 8. Outside Work and Post-Service Employment 19 9. Upholding the Integrity of the Civil Service 21 10. Misconduct in Public Office 23 11. Sources of Advice and Information 25 Annex I - Answers to Some Common Questions asked on Acceptance of Advantages and Entertainment 27 Annex II - Answers to Some Common Questions asked on Misconduct in Public Office 35 FFOREWORD Dear Colleagues, We are privileged to have in Hong Kong a civil service that is acclaimed for its efficiency and honesty. The way our civil service conducts itself is guided by a set of core values that have endured the test of time. These core values have shaped the culture and character of the civil service as we know it today, namely, a clean, professional and meritocratic body of public servants. The qualities of our civil service have taken many years to build and to sustain. Both the Administration and the community recognise that the preservation of these qualities is an essential pillar for effective governance. The publication of this "Guide to Good Practices" underlines our commitment to uphold the fine culture and character of our civil service. In simple language, it sets out the good behaviour expected of civil servants at all levels, including those appointed on non-civil service terms. -

Existing and Planned Measures on the Promotion of Racial Equality Radio

Existing and planned measures on the promotion of racial equality Radio Television Hong Kong Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) is the public service broadcaster of Hong Kong which provides radio, television (TV) and new media services. Services RTHK is devoting part of its radio airtime to provide a Concerned platform for the community, non-government organisations and the underprivileged to participate in broadcasting through the provision of Community Involvement Broadcasting Service (CIBS). Existing Under CIBS, eligible individuals and organisations, Measures including people of diverse race, may apply to produce radio programmes to be broadcast on RTHK. RTHK provides funding support for successful applications to produce programmes under CIBS. CIBS currently provides 17 hours of new programmes per week. Among them, not less than 5 hours are geared specifically to the theme of ethnic minorities. Until now, languages of broadcast programmes include Cantonese, Putonghua, English, African, Arabic, Hakka, Hindi, Japanese, Karnataka, Korean, Nepali, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Spanish, Tagalog, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, and Urdu. Assessment of RTHK will continue to promote CIBS to facilitate the Future Work public’s awareness of and participation in CIBS programmes. Promotional efforts include advertisements on public transports, newspapers and magazines, road shows, social media platforms, radio and TV trailers and supporting activities targeting people of diverse race. Besides, RTHK will continue to invite CIBS producers and talents to participate in various promotional activities, including people of diverse race; and render assistance to those who apply to or produce programmes under CIBS, 1 providing training workshops for producing different programmes by professional producers. Additional RTHK will update and improve the CIBS website so that Measures the public can easily access relevant information on CIBS Taken/To Be applications and programmes. -

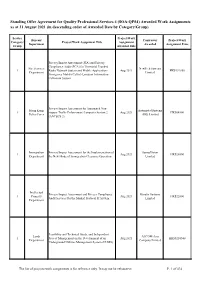

SOA-QPS4) Awarded Work Assignments As at 31 August 2021 (In Descending Order of Awarded Date by Category/Group)

Standing Offer Agreement for Quality Professional Services 4 (SOA-QPS4) Awarded Work Assignments as at 31 August 2021 (in descending order of Awarded Date by Category/Group) Service Project/Work Bureau/ Contractor Project/Work Category/ Project/Work Assignment Title Assignment Department Awarded Assignment Price Group Awarded Date Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) and Privacy Compliance Audit (PCA) for Terrestrial Trunked Fire Services NewTrek Systems 1 Radio Network System and Mobile Application - Aug 2021 HK$192850 Department Limited Emergency Mobile Caller's Location Information Collection System Privacy Impact Assessment for Automated Non- Hong Kong Automated Systems 1 stopper Traffic Enforcement Computer System 2 Aug 2021 HK$64500 Police Force (HK) Limited (ANTECS 2) Immigration Privacy Impact Assessment for the Implementation of SunnyVision 1 Aug 2021 HK$28000 Department the New Mode of Immigration Clearance Operation Limited Intellectual Privacy Impact Assessment and Privacy Compliance Kinetix Systems 1 Property Aug 2021 HK$22800 Audit Services for the Madrid Protocol IT System Limited Department Feasibility and Technical Study, and Independent Lands AECOM Asia 1 Project Management on the Development of an Aug 2021 HK$5210540 Department Company Limited Underground Utilities Management System (UUMS) The list of projects/work assignments is for reference only. It may not be exhaustive. P. 1 of 434 Standing Offer Agreement for Quality Professional Services 4 (SOA-QPS4) Awarded Work Assignments as at 31 August 2021 (in descending order -

The Public Sector in Hong Kong

THE PUBLIC SECTOR IN HONG KONG IN HONG PUBLIC SECTOR THE THE PUBLIC SECTOR IN HONG KONG his book describes and analyses the role of the public sector in the T often-charged political atmosphere of post-1997 Hong Kong. It discusses THE PUBLIC SECTOR critical constitutional, organisational and policy problems and examines their effects on relationships between government and the people. A concluding chapter suggests some possible means of resolving or minimising the difficulties which have been experienced. IN HONG KONG Ian Scott is Emeritus Professor of Government and Politics at Murdoch University in Perth, Australia and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Public and Social Administration at the City University of Hong Kong. He taught at the University of Hong Kong between 1976 and 1995 and was Chair Professor of Politics and Public Administration between 1990 and 1995. Between 1995 and 2002, he was Chair Professor of Government and Politics at Murdoch University. Over the past twenty-five years, he has written extensively on politics and public administration in Hong Kong. G O V E P O L I C Y Professor Ian Scott’s latest book The Public Sector in Hong Kong provides a systematic analysis of Hong Kong’s state of governance in the post-1997 period Ian Scott R and should be read by government officials, politicians, researchers, students and N general readers who seek a better understanding of the complexities of the city’s M government and politics. E — Professor Anthony B. L. Cheung, President, The Hong Kong Institute of Education; N T Member, Hong Kong SAR Executive Council.