“The Heifetz of the Flute.” – GRAMOPHONE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network Ot Create Concerto Pour Flute Et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute Et Piano

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones December 2016 Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network ot Create Concerto Pour Flute et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute et Piano Kelly A. Collier University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Education Commons, and the Music Commons Repository Citation Collier, Kelly A., "Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network to Create Concerto Pour Flute et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute et Piano" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2856. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/10083130 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANDRÉ JOLIVET’S FUSION: MAGICAL MUSIC, CONVENTIONAL LYRICISM, AND JAPANESE INFLUENCES NETWORK TO CREATE CONCERTO POUR FLÛTE ET PIANO AND SONATE POUR FLÛTE ET PIANO By Kelly A. Collier Bachelor of Music University of Nevada, Las Vegas 1999 Master of Music California State University, Long Beach 2001 Master of Music University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2016 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2016 Copyright 2016 Kelly A. -

Nasher Sculpture Center's Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Macke

Nasher Sculpture Center’s Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Mackey to be Performed at City Performance Hall; Guaranteed Seating with Soundings Season Ticket Package Brentano String Quartet Performance of One Red Rose, co-commissioned by the Nasher with Carnegie Hall and Yellow Barn, moved to accommodate bigger audience. DALLAS, Texas (September 12, 2013) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce that the JFK commemorative Soundings concert will be performed at City Performance Hall. Season tickets to Soundings are now on sale with guaranteed seating to the special concert honoring President Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his death with an important new work by internationally renowned composer Steven Mackey. One Red Rose is written for the Brentano String Quartet in commemoration of this anniversary, and is commissioned by the Nasher (Dallas, TX) with Carnegie Hall (New York, NY) and Yellow Barn (Putney, VT). The concert will be held on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 7:30 pm at City Performance Hall with celebrated musicians; the Brentano String Quartet, clarinetist Charles Neidich and pianist Seth Knopp. Mr. Mackey’s One Red Rose will be performed along with seminal works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. An encore performance of One Red Rose, will take place Sunday, November 24, 2013 at 2 pm at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Both concerts will include a discussion with the audience. Season tickets are now available at NasherSculptureCenter.org and individual tickets for the November 23 concert will be available for purchase on October 8, 2013. -

View the 2019 Conductors Guild NYC Conference Program Booklet!

The World´s Only Manufacturer of the Celesta CELESTA ACTION The sound plate is placed above a wooden resonator By pressing the key the felt hammer is set in moti on The felt hammer strikes the sound plate from above CELESTA MODELS: 3 ½ octave (f1-c5) 4 octave (c1-c5) 5 octave (c-c5) 5 ½ octave Compact model (c-f5) 5 ½ octave Studio model (c-f5) (Cabinet available in natural or black oak - other colors on request) OTHER PRODUCTS: Built-in Celesta/Glockenspiel for Pipe Organs Keyboard Glockenspiel „Papageno“ (c2-g5) NEW: The Bellesta: Concert Glockenspiel 5½ octave Compact model, natural oak with wooden resonators (c2-e5) SERVICES: worldwide delivery, rental, maintenance, repair and overhaul Schiedmayer Celesta GmbH Phone Tel. +49 (0)7024 / 5019840 Schäferhauser Str. 10/2 [email protected] 73240 Wendlingen/Germany www.celesta-schiedmayer.de President's Welcome Dear Friends and Colleagues, Welcome to New York City! My fellow officers, directors, and I would like to welcome you to the 2019 Conductors Guild National Conference. Any event in New York City is bound to be an exciting experience, and this year’s conference promises to be one you won’t forget. We began our conference with visits to the Metropolitan Opera for a rehearsal and backstage tour, and then we were off to the Juilliard School to see some of their outstanding manuscripts and rare music collection! Our session presenters will share helpful information, insightful and inspiring thoughts, and memories of one of the 20th Century’s greatest composers and conductors, Pierre Boulez. And, what would a New York event be without a little Broadway, and Ballet? An event such as this requires dedication and work from a committed planning committee. -

Andreas Haefliger Piano

PERSPECTIVES 6 A N D R E A S H A E F L I G E R BEETHOVEN Piano Sonatas Nos. 10 & 30 BERIO Four Encores SCHUMANN Fantasy in C Perspectives 6 Ludwig van Beethoven 1770–1827 Sonata No.10 in G Op.14 No.2 1I Allegro 7’03 2 II Andante 5’02 3 III Scherzo: Allegro assai 3’38 Luciano Berio 1925–2003 4 Erdenklavier 2’49 5 Wasserklavier 2’28 Ludwig van Beethoven Sonata No.30 in E Op.109 6 I Vivace, ma non troppo – Adagio espressivo 4’04 7 II Prestissimo 2’26 8 III Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung 12’26 Luciano Berio 9 Luftklavier 3’25 10 Feuerklavier 2’57 Robert Schumann 1810–1856 Fantasy in C Op. 17 11 I. Durchaus phantastisch und leidenschaftlich vorzutragen 13’39 12 II. Mäßig – Durchaus energisch 7’31 13 III. Langsam getragen – Durchweg leise zu halten 9’34 Andreas Haefliger piano Recorded: 14–16 October 2013, Arc en Scènes, Salle de musique, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Suisse (Schweiz, Switzerland ) Recorded by TRITONUS Musikproduktion GmbH, Stuttgart Recording produced, engineered and edited by Markus Heiland Photography: Marco Borggreve · Design: WLP Ltd. ൿ 2014 The copyright in this sound recording is owned by Andreas Haefliger Ꭿ 2014 Andreas Haefliger. www.andreashaefliger.com Marketed by Avie Records www.avie-records.com When putting together my programmes, I have always seen opportunities to illuminate the individuality of works by placing them in tonal, dramatic and historic relief. Thus, through the sequence of a recital programme, repertoire that has long been familiar to us is shown in a new light. -

50Th Annual Concerto Concert

SCHOOL OF ART | COLLEGE OF MUSICAL ARTS | CREATIVE WRITING | THEATRE & FILM BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY 50th a n n u a l c o n c e r t o concert BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY Summer Music Institute 2017 bgsu.edu/SMI featuring the SESSION ONE - June 11-16 bowling g r e e n Double Reed Strings philharmonia SESSION TWO - June 18-23 emily freeman brown, conductor Brass Recording Vocal Arts SESSION THREE - June 25-30 Musical Theatre saturday, february 25 Saxophone 2017 REGISTRATION OPENS FEBRUARY 1ST 8:00 p.m. For more information, visit BGSU.edu/SMI kobacker hall BELONG. STAND OUT. GO FAR. CHANGING LIVES FOR THE WORLD.TM congratulations to the w i n n e r s personnel of the 2016-2 017 Violin I Bass Trombone competition in music performance Alexandria Midcalf** Nicholas R. Young* Kyle McConnell* Brandi Main** Lindsay W. Diesing James Foster Teresa Bellamy** Adam Behrendt Jef Hlutke, bass Mary Solomon Stephen J. Wolf Morgan Decker, guest Ling Na Kao Cameron M. Morrissey Kurtis Parker Tuba Jianda Bai Flute/piccolo Diego Flores La Le Du Alaina Clarice* undergraduate - performance Nia Dewberry Samantha Tartamella Percussion/ Timpani Anna Eyink Michelle Whitmore Scott Charvet* Stephen Dubetz, clarinet Keisuke Kimura Jerin Fuller+ Elijah T omas Oboe/Cor Anglais Zachary Green+ Michelle Whitmore, flute Jana Zilova* Febe Harmon Violin II T omas Morris David Hirschfeld+ Honorable Mention: Samantha Tartamella, flute Sophia Schmitz Mayuri Yoshii Erin Reddick+ Bethany Holt Anthony Af ul Felix Reyes Zi-Ling Heah Jamie Maginnis Clarinet/Bass clarinet/ Harp graduate - performance Xiangyi Liu E-f at clarinet Michaela Natal Lindsay Watkins Lucas Gianini** Keyboard Kenneth Cox, flute Emily Topilow Hayden Giesseman Paul Shen Kyle J. -

Discovering the Contemporary Relevance of the Victorian Flute Guild

Discovering the Contemporary Relevance of the Victorian Flute Guild Alice Bennett © 2012 Statement of Responsibility: This document does not contain any material, which has been accepted for the award of any other degree from any university. To the best of my knowledge, this document does not contain any material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference is given. Candidate: Alice Bennett Supervisor: Dr. Joel Crotty Signed:____________________ Date:____________________ 2 Contents Statement of Responsibility: ................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter One ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Literature Review ................................................................................................................................ 9 Chapter Outlines ............................................................................................................................... 11 Chapter Two ......................................................................................................................................... -

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

The Canadian Clarinet Works Written for James Campbell

THE CANADIAN CLARINET WORKS WRITTEN FOR JAMES CAMPBELL by Laura Chalmers Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Eli Eban, Research Director and Chair __________________________________________ James Campbell __________________________________________ Kathleen McLean __________________________________________ Peter Miksza September 29, 2020 ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to the following people, without whom this document would not have been completed: To Prof. Campbell, Allan Gilliland, Phil Nimmons, Timothy Corlis, and Jodi Baker Contin, who gave their time and shared their recollections with me. To my wonderful friends, Emory Rosenow, Laura Kellogg, Mark Wallace, and Lilly Haley- Corbin, who not only read through this entire document to correct mistakes, but who also encouraged me and bolstered me as I wrote this paper. To my family, Mom, Marcus, and Leisha, who have always supported me and continue to do so through my Doctorate. Finally, to my husband, Jacob Darrow. This is as much his success as it is mine. iii Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................... -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

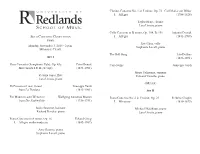

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

Melbourne Suburb of Northcote

ON STAGE The Autumn 2012 journal of Vol.13 No.2 ‘By Gosh, it’s pleasant entertainment’ Frank Van Straten, Ian Smith and the CATHS Research Group relive good times at the Plaza Theatre, Northcote. ‘ y Gosh, it’s pleasant entertainment’, equipment. It’s a building that does not give along the way, its management was probably wrote Frank Doherty in The Argus up its secrets easily. more often living a nightmare on Elm Street. Bin January 1952. It was an apt Nevertheless it stands as a reminder The Plaza was the dream of Mr Ludbrook summation of the variety fare offered for 10 of one man’s determination to run an Owen Menck, who owned it to the end. One years at the Plaza Theatre in the northern independent cinema in the face of powerful of his partners in the variety venture later Melbourne suburb of Northcote. opposition, and then boldly break with the described him as ‘a little elderly gentleman The shell of the old theatre still stands on past and turn to live variety shows. It was about to expand his horse breeding interests the west side of bustling High Street, on the a unique and quixotic venture for 1950s and invest in show business’. Mr Menck was corner of Elm Street. It’s a time-worn façade, Melbourne, but it survived for as long as consistent about his twin interests. Twenty but distinctive; the Art Deco tower now a many theatres with better pedigrees and years earlier, when he opened the Plaza as a convenient perch for telecommunication richer backers.