Antitrust Law on the Borderland of Language and Market Definition: Is There a Separate Spanish- Language Radio Market? Catherine J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Annual Report

Entravision Communications Corporation 2007 Annual Report EVC | 2007 Entravision Communications Corporation Entravision Communications Corporation is the largest publicly held, Spanish-language media company in the United States, with television and radio broadcast properties clustered in many of the A Nation of fastest-growing and highest-density major U.S. Hispanic markets. Entravision is the largest affiliate group of Univision Communications Inc. and owns and/or operates Immigrants 51 primary television stations, 23 of which are Univision Network affiliates and 18 TeleFutura Network affiliates. In addition, Entravision owns 48 radio stations, 37 of which broadcast in Spanish and 11 in English, primarily to Hispanic audiences. These stations are located in 19 U.S. markets with large Hispanic populations, mainly in the Southwest. Entravision’s headquarters are located in Santa Monica, California. The company’s stock trades on The New York Stock Exchange under the symbol “EVC.” Margaret Garcia about the cover un nuevo mestizaje series | the new mix This Report features representative works of the “Chicano art 16 works, 1987-2001 movement,” a broad, artistic expression of the quest for ethnic Oil on canvas, 96” x 96” overall identity, memory preservation, and cultural reclamation in the quotidian lives of Mexican-Americans in the Southwestern United States. page | two page | three Because Entravision’s media serve as an important voice of the Hispanic community in our markets, we have chosen in this Annual Report to add our views to the debate on the role of immigrants and particularly Hispanic immigrants in our society. give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free There was no “Statue of Liberty” to welcome Mexican immigrants at Eagle Pass, Texas, Nogales, Arizona, or Columbus, New Mexico in 1907, but records in the National Archives list their names, along with Syrians, Turks and Japanese who entered at the same places and times. -

View Annual Report

a day in the life | entravision communications corporation 2006 annual report a day in the life | book one Entravision Communications Corporation is the second larg- est Spanish-language media company in the United States, with television and radio broadcast properties and outdoor advertising operations clustered in many of the fastest- growing and highest-density major U.S. Hispanic markets. financial highlights Entravision media reach approximately two-thirds of the 42.7 million U.S. Hispanic population. 2006 vs 2005 Entravision is the largest affiliate group of Univision and in thousands, except share and per share data 2006 2005 % change 2004 owns and/or operates 51 primary television stations, of which 23 are Univision Network affiliates and 18 TeleFu- Net revenue $ 291,752 $ 280,964 4 $ 259,053 tura Network affiliates. In addition, Entravision owns and Operating expenses 175,791 172,040 2 162,366 operates 47 Spanish-language radio stations in 18 U.S. Consolidated adjusted EBITDA 100,081 92,473 8 79,956 markets, primarily in the Southwest, with large Hispanic Net income (loss) (134,599) (9,657) – 6,164 populations. Net loss per share, basic and diluted $ (1.27) $ (0.08) – $ (0.09) The company’s outdoor advertising operations consist of Weighted average common shares approximately 10,600 outdoor billboard facings in predomi- outstanding, basic and diluted 106,078,486 124,293,792 – 105,758,136 nantly Hispanic neighborhoods of Los Angeles and New York City, the #1 and #2 Hispanic markets in the United States, respectively, as well as transit advertising in Fresno and Sacramento, California and Tampa, Florida. -

Entravision Communications Corp

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-K Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d) Filing Date: 2007-03-15 | Period of Report: 2006-12-31 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-07-055499 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER ENTRAVISION COMMUNICATIONS CORP Mailing Address Business Address 2425 OLYMPIC BLVD 2425 OLYMPIC BLVD CIK:1109116| IRS No.: 954783236 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 STE 6000 WEST STE 6000 WEST Type: 10-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-15997 | Film No.: 07696138 SANTA MONICA CA 90404 SANTA MONICA CA 90404 SIC: 4833 Television broadcasting stations 3104473870 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTIONS 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2006 OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Transition Period from to Commission File Number 1-15997 ENTRAVISION COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 95-4783236 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 2425 Olympic Boulevard, Suite 6000 West Santa Monica, California 90404 (Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) Registrants telephone number, including area code: (310) 447-3870 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Class A Common Stock The New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

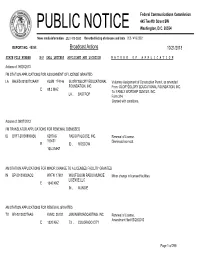

PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C

REPORT NO. PN-1-210603-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 06/03/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000149107 Renewal of FM KRST 12584 Main 92.3 ALBUQUERQUE RADIO LICENSE 06/01/2021 Accepted License , NM HOLDING CBC, LLC For Filing From: To: 0000149134 Renewal of FX K206DK 50785 Main 89.1 BULLHEAD CITY NEW LIFE 06/01/2021 Accepted License , AZ CHRISTIAN SCHOOL For Filing From: To: 0000148933 Minor LPD W22FJ-D 187453 22 DUBOIS, PA Lowcountry 34 Media, 06/01/2021 Accepted Modification LLC For Filing From: To: 0000149302 Renewal of FX K292BS 4455 Main 106.3 OASIS VALLEY, BEATTY TOWN 06/01/2021 Accepted License NV ADVISORY COUNCIL For Filing From: To: 0000148336 Renewal of FM KKSS 63928 Main 97.3 SANTA FE, NM AGM NEVADA, LLC 05/28/2021 Accepted License For Filing From: To: 0000149158 Renewal of FM KLUC- 47744 Main 98.5 LAS VEGAS, NV AUDACY LICENSE, 06/01/2021 Accepted License FM LLC For Filing From: To: Page 1 of 80 REPORT NO. PN-1-210603-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 06/03/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000148879 Renewal of FM KTDX 93647 Main 89.3 LARAMIE, WY Educational 06/01/2021 Accepted License Communications of For Filing Colorado Springs, Inc. -

RADIO STATION AUTHORIZATION Kmis0

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION RADIO STATION AUTHORIZATION kMiS0 Name: Entravision Communications Corporation Call Sign: Authorization Type: Section 325(c) File Number: 325-NEW-200609 15-00003 Grant date: 12/06/2006 Expiration Date: 12/06/2011 Subject to the provisions of the Communications Act of 1934, subsequent Acts, and Treaties, and Conmiission Rules made thereunder, and further subject to conditions set forth in this permit, the PERMITTEE: Entravision Communications Corporation is hereby authorized to locate, use, or maintain a studio in the United States for the purpose of supplying program material to foreign broadcast stations for the term ending December 6, 2011 (3 AM Eastern Standard Time). Particulars of Operations A) Studio Location: 801 N. Jackson McAllen, TX 78501 B) For the purpose of producing programs consisting of: Programming will be delivered to Station XHRIO-TV, Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico, licensed to TV Norte, S.A. de C.V. The station operates on Channel 2 with an authorized power of 98.56 kW. The programming supplied by the applicant will be varied in nature. It will be primarily entertainment programming, but will also include news, sports, and public affairs programming. C) To be delivered by means of: Common Carrier, satellite, radio microwave link, D) To stations identified and located as follows: Call Sign Channel Station Locations(s) XHRIO 2 Matamoros, Tamaulipa, Mexico The Commission reserves the right during said permit period of terminating this permit or making effective any changes or modifications of this permit which may be necessary to comply with any decision of the Commission rendered as a result of any such hearing which has been designated but not held, prior to the commencement of this permit period. -

Arizona Commercial Radio Stations + ABA Members

Arizona Commercial Radio stations + ABA Members REGION CITY OWNERSHIP STATION AM/FM FREQ FORMAT WEBSITE KEY CONTACT EMAIL PHONE Metro Phoenix Apache Jctn 1TV.com Inc KBSZ AM 1260 Classic Rock http://rattler973.com/ Bill Pettus [email protected] 213-910-1226 Metro Phoenix Apache Jctn 1TV.com Inc KIKO FM 96.5 Classic Hits/Oldies 965oldies.com Bill Pettus [email protected] 213-910-1226 Metro Phoenix Claypool 1TV.com Inc KIKO AM 1340 Country/AC http://bull1340.com/ Bill Pettus [email protected] 213-910-1226 Metro Phoenix Globe Globecasting, Inc KQSS FM 101.9 Country http://www.kqss.net Rollye James [email protected] 928-425-8255 Metro Phoenix Globe Globecasting, Inc KJAA AM 1240 Oldies http://www.kjaa.us Rollye James [email protected] 928-425-8255 Metro Phoenix Globe Globecasting, Inc KJAA FM 106.1 Oldies http://www.kjaa.us Rollye James [email protected] 928-425-8255 Metro Phoenix Globe Linda C. Corso KRDE FM 94.1 Country http://www.krde.com/ Linda Corso [email protected] 928-402-9222 Metro Phoenix Mesa East Valley Institute of Technology KPNG FM 88.7 Adult Top 40 https://pulseradio.fm/ Steve Grosz [email protected] 480-461-4049 Metro Phoenix Mesa East Valley Institute of Technology KVIT FM 90.7 Variety Hits http://www.neon907.com/ Steve Grosz [email protected] 480-461-4049 Metro Phoenix Phoenix Bonneville International KMVP FM 98.7 Sports Talk https://arizonasports.com/ Jeff Clewett [email protected] 602-200-2627 Metro Phoenix Phoenix Bonneville International KTAR AM 620 Sports http://arizonasports.com/streams/ktaram.phpDave Zadrozny -

For Public Inspection Comprehensive

REDACTED – FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION COMPREHENSIVE EXHIBIT I. Introduction and Summary .............................................................................................. 3 II. Description of the Transaction ......................................................................................... 4 III. Public Interest Benefits of the Transaction ..................................................................... 6 IV. Pending Applications and Cut-Off Rules ........................................................................ 9 V. Parties to the Application ................................................................................................ 11 A. ForgeLight ..................................................................................................................... 11 B. Searchlight .................................................................................................................... 14 C. Televisa .......................................................................................................................... 18 VI. Transaction Documents ................................................................................................... 26 VII. National Television Ownership Compliance ................................................................. 28 VIII. Local Television Ownership Compliance ...................................................................... 29 A. Rule Compliant Markets ............................................................................................ -

Programming on Radio Stations in the U.S. Spanish

Programming on Radio Stations in the U.S. WIOB -FM Mn Arbor MI KOMP(FM) Las Vegas NV WPHD(FM) Tioga PA ' WRFW(FM) River Falls WI KWKW(AM) Los Angeles CA 'WCHW -FM Bay City MI KDDT(FM) Reno NV WOWK(FM) University Park PA ' WSHS(FM) Sheboygan WI KHOT(AM) Madera CA WBRN -FM Big Rapids MI KRZO -FM Sparks NV ' WRKC(FM) Wilkes -Barre PA WJJO(FM) Watertown WI KMMM(FM) Madera CA WRIF(FM) Detroit MI KHWK(FM) Tonopah NV 'WVYC(FM) York PA WHTL -FM Whitehall WI KZFO(FM) Madera CA WGFN(FM) Glen Arbor MI ' WCDD(FM) Albany NY WMEG(FM) Guayama PR WGLX -FM Wisconsin Rapids WI KRCX -FM Marysville CA WJZJ(FM) Glen Arbor MI WPYX(FM) Albany NY WCAD(FM) San Juan PR ' WCDE(FM) Elkins WV KSUV -FM McFarland CA WKLT(FM) Holland MI ' WETD(FM) Alfred NY WIAC -FM San Juan PR WRLF(FM) Fairmont WV ' KFPO(FM) Modesto CA WKLT(FM) Kalkaska MI WOSP(FM) Arlington NY 'WORI(FM) Bristol RI WKMZ(FM) Martinsburg WV KJAZ(AM) Oroville CA WRXF(FM) Lapeer MI WBAB-FM Babylon NY WBRU(FM) Providence RI WAMX(FM) Milton WV KZCY(FM) Oroville CA WLJZ(FM) Mackinaw City MI WXCR(FM) Ballston Spa NY WHJY(FM) Providence RI WHBR -FM Parkersburg WV KOXR(AM) Oxnard CA WKMZ(FM) Midland MI 'WGCC -FM Batavia NY WXEX(FM) Wakefield - WCOZ(AM) St. Albans WV KXLM(FM) Oxnard CA 'WEJY(FM) Monroe MI -WKRB(FM) Brooklyn NY Peacedale RI WZST(FM) Westover WV KUTY(AM) Palmdale CA WAOR(FM) Niles MI WISY(FM) Canandaigua NY WSUY(FM) Charleston SC WEGW(FM) Wheeling WV KZMS(FM) Patterson CA ' WOSS(FM) Ontonagon MI 'WHCL -FM Clinton NY WARO(FM) Columbia SC KZCY(FM) Cheyenne WY KZSA(FM) Placerville CA 'WBLD(FM) Orchard Lake MI WCDW(FM) Conklin NY WAVF(FM) Hanahan SC KMTN(FM) Jackson WY KCAL(AM) Redlands CA WKLZ -FM Petoskey MI ' WCEB(FM) Coming NY WKZO -FM Myrtle Beach SC KDIF(AM) Riverside CA 'WSGR -FM Port Huron MI 'WSUC -FM Cortland NY KSOY(FM) Deadwood SD KSSE(FM) Riverside CA WRKR(FM) Portage MI WEHM(FM) East Hampton NY 'KAUR(FM) Sioux Falls SD Russian KLIB(AM) Roseville CA WGER -FM Saginaw MI WKLL(FM) Frankton NY ' KAOR(FM) Vermillion SD WKTA(AM) Evanston IL KBMB(FM) Sacramento CA WSUE(FM) Sault Ste. -

Broadcast Actions 10/21/2013

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48098 Broadcast Actions 10/21/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 09/26/2013 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED LA BALED-20130712AAW KJGM 174146 GLORY2GLORY EDUCATIONAL Voluntary Assignment of Construction Permit, as amended FOUNDATION, INC. From: GLORY2GLORY EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION, INC. E 88.3 MHZ To: FAMILY WORSHIP CENTER, INC. LA , BASTROP Form 314 Granted with conditions. Actions of: 09/27/2013 FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED ID BRFT-20130806ABU K287AG RADIO PALOUSE, INC. Renewal of License. 150431 Dismissed as moot. E ID ,MOSCOW 105.3 MHZ AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MINOR CHANGE TO A LICENSED FACILITY GRANTED IN BP-20130802ACQ WXFN 17601 WOOF BOOM RADIO MUNCIE Minor change in licensed facilities. LICENSE LLC E 1340 KHZ IN , MUNCIE AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED TX BR-20130227AAG KVMC 30102 JIMLIN BROADCASTING, INC. Renewal of License. Amendment filed 03/28/2013 E 1320 KHZ TX , COLORADO CITY Page 1 of 299 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48098 Broadcast Actions 10/21/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 09/27/2013 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED AZ BR-20130402AAD KNTR 38310 STEVEN M. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

Suction Dredge Scoping Report-Appendix B-Press Release

DFG News Release Public Scoping Meetings Held to Receive Comments on Suction Dredge Permitting Program November 2, 2009 Contact: Mark Stopher, Environmental Program Manager, 530.225.2275 Jordan Traverso, Deputy Director, Office of Communications, Education and Outreach, 916.654.9937 The Department of Fish and Game (DFG) is holding public scoping meetings for input on its suction dredge permitting program. Three meetings will provide an opportunity for the public, interested groups, and local, state and federal agencies to comment on potential issues or concerns with the program. The outcome of the scoping meetings and the public comment period following the scoping meetings will help shape what is studied in the Subsequent Environmental Impact Report (SEIR). A court order requires DFG to conduct an environmental review of the program under the California Environmental Quality Act. DFG is currently prohibited from issuing suction dredge permits under the order issued July 9. In addition, as of August 6, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's signing of SB 670 (Wiggins) places a moratorium on all California instream suction dredge mining or the use of any such equipment in any California river, stream or lake, regardless of whether the operator has an existing permit issued by DFG. The moratorium will remain in effect until DFG completes the environmental review of its permitting program and makes any necessary updates to the existing regulations. The scoping meetings will be held in Fresno, Sacramento and Redding. Members of the public can provide comments in person at any of the following locations and times: Fresno: Monday, Nov. 16, 5 p.m.