Education Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Ian Wooldridge Director

Ian Wooldridge Director For details of Ian's freelance productions, and his international work in training and education go to www.ianwooldridge.com Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, ROYAL LYCEUM THEATRE COMPANY, EDINBURGH, 1984-1993 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company, Edinburgh MERLIN Royal Lyceum Theatre Tankred Dorst Company Edinburgh ROMEO AND JULIET Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh THE CRUCIBLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE ODD COUPLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Neil Simon Company Edinburgh JUNO AND THE PAYCOCK Royal Lyceum Theatre Sean O'Casey Company Edinburgh OTHELLO Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE HOUSE OF BERNARDA ALBA Royal Lyceum Theatre Federico Garcia Lorca Company Edinburgh HOBSON'S CHOICE Royal Lyceum Theatre Harold Brighouse Company Edinburgh DEATH OF A SALESMAN Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE GLASS MENAGERIE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh ALICE IN WONDERLAND Royal Lyceum Theatre Adapted from the novel by Lewis Company, Edinburgh Carroll A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh THE NUTCRACKER SUITE Royal Lyceum -

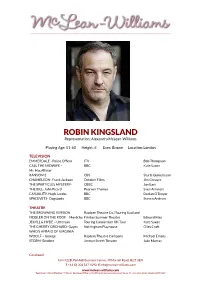

Mwm Cv Robinkingsland 2

ROBIN KINGSLAND Representation: Alexandra McLean-Williams Playing Age: 51-60 Height: 6’ Eyes: Brown Location: London TELEVISION EMMERDALE - Police Officer ITV Bob Thompson CALL THE MIDWIFE – BBC Kate Saxon Mr. MacAllister RANSOM 3 CBS Sturla Gunnarsson CHAMELEON- Frank Jackson October Films Jim Greayer THE SPARTICLES MYSTERY- CBBC Jon East THE BILL- John Picard Pearson Thames Sven Arnstein CASUALITY-Hugh Jacobs BBC Declan O’Dwyer SPACEVETS- Dogsbody BBC Steven Andrew THEATRE THE BROWNING VERSION Rapture Theatre Co,/Touring Scotland FIDDLER ON THE ROOF – Mordcha Frinton Summer Theatre Edward Max JEKYLL & HYDE – Utterson Touring Consortium UK Tour Kate Saxon THE CHERRY ORCHARD- Gayev Nottingham Playhouse Giles Croft WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF – George Rapture Theatre Company Michael Emans STORM- Brother Jermyn Street Theatre Jake Murray Continued Unit F22B, Parkhall Business Centre, 40 Martell Road, SE21 8EN T +44 (0) 203 567 1090 E [email protected] www.mclean-williams.com Registered in England Number: 7432186 Registered Office: C/O William Sturgess & Co, Burwood House, 14 - 16 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QY ROBIN KINGSLAND continued PRIVATE LIVES – Victor Mercury Theatre Colchester Esther Richardson ROMEO & JULIET – Montague Crucible Theatre Sheffield Jonathan Humphreys ARCADIA – Captain Bruce Nottingham Playhouse Giles Croft HAMLET- Claudius Secret Theatre, Edinburgh Fringe Richard Crawford Festival THE OTHER PLACE – Ian Smithson RADA Geoffrey Williams WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION Vienna English Theatre, Philip Dart Sir Wilfrid -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham. -

Lunch by Steven Berkoff Premiering July 9, 2021 7:30PM Streaming July 9-13, 2021

Lunch by Steven Berkoff Premiering July 9, 2021 7:30PM Streaming July 9-13, 2021 Lunch By Steven Berkoff Directed by Richard Romagnoli Man Bill Army* Woman Jackie Sanders* A bench by the seaside. The present day. * member of Actors’ Equity Association, the union of professional Actors and Stage Managers 2 A Note from the Director: LUNCH is a terse, scabrous, poetic dance between A Man and A Woman. The text provides only spare biographies, enough to tweak our interest and lead to endless speculation. Do the characters have a shared history? Are they a couple? Is their encounter a contrivance, a fantasy with unanticipated consequences? Do they really know Prufrock? The production only explores these questions. In a brief 40 minutes Berkoff presents characters in mid-life, stepping out of their familiar routines to passionately and humorously engage the other in what critic Aleks Sierz has correctly named, “in-yer-face theatre,” describing certain young British writers of the ‘90’s and the millennium. Berkoff can certainly be considered one of the progenitors of this style. This is as bare knuckled as “in-yer- face” gets or --as PTP once described its work --“I only laugh when it hurts”. Hope you enjoy. Steven Berkoff was born in Stepney, London. After studying drama and mime in London and Paris, he entered a series of repertory companies and in 1968 formed the London Theatre Group. His plays and adaptations have been performed in many countries and in many languages. Among the many adaptations Berkoff has created for the stage, directed and toured, are Kafka’s Metamorphosis and The Trial, Agamemnon, and Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. -

Western Europe

Western Europe Great Britain National Affairs J. HE GOVERNMENT SHOWED surprising stability in 1985, despite the continuing economic slowdown, labor difficulties, and growing racial unrest. The strike by the National Union of Mineworkers, which had begun in March 1984, ended a year later with the workers agreeing to accept reduced terms and the government going ahead with its program of pit closures. Another indicator of weakening trade-union strength was an abortive strike in August by the National Union of Railwaymen, whose protest failed to halt the introduction of driver-only trains. Elsewhere on the labor front, a breakdown in teachers' pay talks in February was followed in July by strikes, which continued with growing intensity during the autumn. Unemployment in Britain remained at around 3.4 million during the year, some 14 percent of the labor force. On the economic front, the year began with the pound at a record low of $1.1587. When it plunged to below $1.10 in February, interest rates were raised from 12 to 14 percent, which helped stem the decline. Racism and Anti-Semitism Racial and social tensions in British society erupted in violence on several occa- sions during the year. In September police in riot gear battled black youths in Handsworth (Birmingham) and Brixton (London); in October a policeman was stabbed to death in an outbreak in Tottenham in which, for the first time, rioters fired shots at police. The number of police and civilians injured in riots during the year reached 254. Right-wing National Front (NF) members were increasingly implicated in vio- lence at soccer matches. -

8330 Jewish History Book

Cultural Exploring the vanishing Walks 1&2 Jewish East End night ‘hang out’. ‘The Waste’, as it was called, along Introduction Whitechapel, was another place of adventure and I worked there for a while for a man who called himself the ‘Pen By Steven Berkoff, King’. I worked for him occasional Saturdays and I believe still resident in the East End it was here that I first got my taste for acting. Eventually The East End, as I knew it from our family was re-housed to a council flat in Manor House, the brief time I spent there after N4. But for years I would take the No. 653 bus back to the the war, was a place of constant East End. I somehow found it hard to get away. activity. In the summer, my street mates and I would go swimming © Steven Berkoff 2003 by Tower Bridge; tons of sand had been placed on the shore Walk 1 and it became the Cockney’s Riviera. After a vigorous swim, it would be a treat to go to the Lyon’s teashop in Aldgate and avail ourselves of the Aldgate to Whitechapel Library goodies to be had there, tomato soup with mashed potatoes being the favourite. Artists, Cigarmakers and Markets Naturally Sunday morning in the ‘Lane’ was a must and a Starting point St. Botolph’s, Aldgate place to haggle with stamp collectors, since I was an avid Finishing point Whitechapel Library philatelist in those days. Weeknights were spent at the Oxford and St. George’s Boys Club in Berner Street, where I Estimate time 2.25 hours acquired high skills in ‘ping pong’, the working man’s tennis. -

Press Information

Press Information New Writing at the Finborough Theatre Season November 2011 to January 2012 Papatango Theatre Company in partnership with the Finborough Theatre present four world premieres The Papatango Playwriting Festival 2011 Foxfinder by Dawn King Through The Night by Matt Morrison Rigor Mortis by Carol Vine Crush by Rob Young Papatango have teamed up with one of London's leading new writing venues, the Finborough Theatre to present the winning entries in the 2011 Papatango Playwriting Competition 2011, featuring this year's winning play Foxfinder by Dawn King which will play for a four week limited season from 29 November (Press Night: Thursday, 1 December 2011 at 8.30pm) and three runners up who will each receive a one week run – Through The Night by Matt Morrison (Press Night: Wednesday, 7 December 2011 at 6.30pm), Rigor Mortis by Carol Vine (Press Night: Wednesday, 14 December 2011 at 6.30pm) and Crush by Rob Young (Press Night: Tuesday, 20 December 2011 at 6.30pm). Papatango was founded by Matt Roberts, George Turvey and Sam Donovan in 2007. The company's mission is to find the best and brightest new talent in the UK with an absolute commitment to bring their work to the stage. Since then, Papatango have produced eight pieces of new writing in such venues as the Tristan Bates Theatre, the Old Red Lion Theatre and the Pleasance London. 2009 saw the launch of their first Papatango New Writing Competition, which each year has gone from strength to strength. Winners of previous competitions have won much acclaim from the press and profession including – for Angel by Matt Grinter at the Pleasance London – “Riveting performances….powerfully directed” (Jeremy Kingston, The Times critic), and “A great piece of theatre” (Steven Berkoff) and, for Potentials by Dominic Mitchell at the Tristan Bates Theatre, which was awarded four stars byWhatsOnStage, “Potentials was beautifully observed, conceived and the performances strong, witty and true. -

Berkoff's Collision with Aeschylus and Sophocles

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2004 Plague, Pestilence & Pollution : Berkoff's Collision With Aeschylus and Sophocles Michelle Aslett Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons Recommended Citation Aslett, M. (2004). Plague, Pestilence & Pollution : Berkoff's Collision With Aeschylus and Sophocles. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/951 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/951 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Pl-a~ue, Pesttlence filerK~.>ff' s Cl>!lisil>n With Aeseh\.1! us J . and sl>rhl>cles Michelle Aslett (2002505) Bachelor of Arts (Drama Studies)- Honours faculty of Community SeJVices, Education and Social Sciences Edith Cowan University Principal SupeJVisor- Dr. Susan Ash 25. 01. 2004 USE OF THESIS The Use of Thesis statement is not included in this version of the thesis. -

ADAPTED by STEVEN BERKOFF at 100% A4 Landscape for Best Results

METAMORPHOSIS ADAPTED BY STEVEN BERKOFF THE STREET PRESENTS SYNOPSIS Gregor Samsa is a young man with a bright future. He has served as a soldier, he works hard and is unfalteringly polite. He plans to support his sister’s violin education and keeps his mother and father in the comfort they have become accustomed to in their retirement. Until one day, METAMORPHOSIS Gregor oversleeps his morning alarm and discovers he has become ADAPTED BY STEVEN BERKOFF a gigantic insect…. FROM THE FRANZ KAFKA NOVELLA The action of Metamorphosis takes place inside the Samsa apartment in a modern de-industrialised landscape spanning 17—31 August 2019 “Yes, I know I’m covered in the 20th – 21st century. The Street Theatre, Canberra grime and muck – and you all detest me” — Gregor Scene 1 THE SAMSA FAMILY Scene 2 GREGOR IN THE MORNING AND A VISIT FROM THE CHIEF CLERK Scene 3 FEEDING GREGOR Scene 4 FAMILY DILEMMAS AND REMINISCES Scene 5 GREGOR’S DREAMS THEATRE—MUSIC—COMEDY Scene 6 OPTIMISM AND THE LODGERS PRODUCTION CREDITS PRODUCTION TEAM Scene 7 MOVING ON Cast (in order of appearance) STAGE MANAGER Lydia Kelly ABOUT THE WRITER RUTH PIELOOR Mrs Samsa LIGHTING OPERATOR CHRISTOPHER SAMUEL CARROLL William Malam Mr Samsa SOUND OPERATOR Steven Berkoff STEFANIE LEKKAS Greta Lydia Kelly Writer DYLAN VAN DEN BERG Gregor MAKE-UP ASSISTANT PJ WILLIAMS Chief Clerk Varara Naumova* Writer, theatre director and actor Steven Berkoff was SET BUILD born in 1937, East London. Educated at the Raines CREATIVE TEAM Imogen Keen Foundation Grammar School, he trained to be an Luke Laffan actor at the Webber Douglas Academy in London, WRITER Anthony Theobald and later in Paris at the École Internationale de Steven Berkoff STAGE TECHNICIANS Théâtre de Jacques Lecoq. -

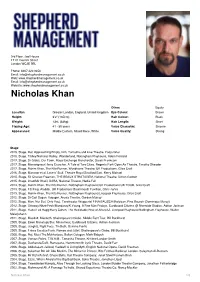

Nicholas Khan

3rd Floor, Joel House 17-21 Garrick Street London WC2E 9BL Phone: 0207 420 9350 Email: [email protected] Web: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk Email: [email protected] Website: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk Nicholas Khan Other: Equity Location: Greater London, England, United Kingdom Eye Colour: Brown Height: 6'2" (187cm) Hair Colour: Black Weight: 13st. (83kg) Hair Length: Short Playing Age: 41 - 50 years Voice Character: Sincere Appearance: Middle Eastern, Mixed Race, White Voice Quality: Strong Stage 2019, Stage, Raf, Approaching Empty, Kiln, Tamasha and Live Theatre, Pooja Ghai 2018, Stage, Tilsley/Nicholas Ridley, Wonderland, Nottingham Playhouse, Adam Penford 2017, Stage, Dr Gibbs, Our Town, Royal Exchange Manchester, Sarah Frankcom 2017, Stage, Monseigneur/ Jerry Cruncher, A Tale of Two Cities, Regents Park Open Air Theatre, Timothy Sheader 2017, Stage, Rahim Khan, The Kite Runner, Wyndhams Theatre/ UK Productions, Giles Croft 2016, Stage, Mansoor et al, Love n' Stuff, Theatre Royal Stratford East, Kerry Michael 2015, Stage, Sir Charles Freeman, THE BEAUX STRATAGEM, National Theatre, Simon Godwin 2015, Stage, Imad/Mir Khalil, DARA, National Theatre, Nadia Fall 2014, Stage, Rahim Khan, The Kite Runner, Nottingham Playhouse/UK Productions/UK TOUR, Giles Croft 2013, Stage, PC Ping, Aladdin, UK Productions Bournmouth Pavillion, Chris Jarvis 2013, Stage, Rahim Khan, The Kite Runner, Nottingham Playhouse/Liverpool Playhouse, Giles Croft 2012, Stage, Dr Carl Sagan, Voyager, Arcola Theatre, Gordon Murray 2012, Stage,