The Newcastle City-Wide Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keeping in Touch

KOTARA HIGH SCHOOL Lexington Parade, Adamstown NSW 2289 Phone: 0249433044 Fax: 0249421049 Email: [email protected] Keeping In Touch The next P&C Meeting for 2016 is on Monday 15th August. at 7pm in the LIBRARY in D Block (All Parents and Carers are invited) Principal’s Report I sincerely hope that Semester Two Term Three has started off positively for our community. I have always seen Term Three as the real business end of the year for secondary schools. By the end of this term Year Twelve have completed their studies and would have graduated at their final assembly on the last day of term. So it is a time when all staff are completing courses, revising, supporting students with specific external projects and completing Higher School Certificate paperwork. I sincerely wish all of Year Twelve the best for this term and I hope that they maximise their final term of schooling. Our senior debating team this term successfully made it to the state semi-finals of the Premier’s Debating Competition. They were narrowly defeated by North Sydney Girls High School but have had amazing success reaching this stage of the competition. Debating is very competitive in this region, let alone on a state level, and I would like to congratulate the whole team – Ben Frohlich, Alena Payne, Sofia Davey, Jake Rexter and Kiera Hayden for their effort and success, as well as Ms Scobie, Ms Harrip and Alexandra Yates for their support and commitment to the team and debating at Kotara High School. -

Lower Hunter Regional Conservation Plan Cover Photos (Main Image, Clockwise): Hunter Estuaries (DECC Estuaries Unit) Mother and Baby Flying Foxes (V

Lower Hunter Regional Conservation Plan Cover photos (main image, clockwise): Hunter estuaries (DECC Estuaries Unit) Mother and baby flying foxes (V. Jones, DECC) Lower Hunter estuary, Hunter Wetlands National Park (G. Woods, DECC) Sugarloaf Range (M. van Ewijk, DECC) Published by: Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW 59 Goulburn Street PO Box A290 Sydney South 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au © Copyright State of NSW and Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW. The Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced for educational or non-commercial purposes in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specifi c permission is required for the reproduction of photographs and images. The material provided in the Lower Hunter Regional Conservation Plan is for information purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for legal advice in relation to any matter, whether particular or general. This document should be cited as: DECCW 2009, Lower Hunter Regional Conservation Plan, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW, Sydney. ISBN 978 1 74232 515 6 DECCW 2009/812 First published April 2009; Revised December 2009 Addendum In the Gwandalan Summerland Point Action Group Inc v. Minister for Planning (2009) NSWLEC 140 (Catherine Hill Bay decision), Justice Lloyd held that the decisions made by the Minister for Planning to approve a concept plan and project application, submitted by a developer who had entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and Deed of Agreement with the Minister for Planning and the Minister for Climate Change and the Environment were invalid. -

Hunter Investment Prospectus 2016 the Hunter Region, Nsw Invest in Australia’S Largest Regional Economy

HUNTER INVESTMENT PROSPECTUS 2016 THE HUNTER REGION, NSW INVEST IN AUSTRALIA’S LARGEST REGIONAL ECONOMY Australia’s largest Regional economy - $38.5 billion Connected internationally - airport, seaport, national motorways,rail Skilled and flexible workforce Enviable lifestyle Contact: RDA Hunter Suite 3, 24 Beaumont Street, Hamilton NSW 2303 Phone: +61 2 4940 8355 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rdahunter.org.au AN INITIATIVE OF FEDERAL AND STATE GOVERNMENT WELCOMES CONTENTS Federal and State Government Welcomes 4 FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Australia’s future depends on the strength of our regions and their ability to Introducing the Hunter progress as centres of productivity and innovation, and as vibrant places to live. 7 History and strengths The Hunter Region has great natural endowments, and a community that has shown great skill and adaptability in overcoming challenges, and in reinventing and Economic Strength and Diversification diversifying its economy. RDA Hunter has made a great contribution to these efforts, and 12 the 2016 Hunter Investment Prospectus continues this fine work. The workforce, major industries and services The prospectus sets out a clear blueprint of the Hunter’s future direction as a place to invest, do business, and to live. Infrastructure and Development 42 Major projects, transport, port, airports, utilities, industrial areas and commercial develpoment I commend RDA Hunter for a further excellent contribution to the progress of its region. Education & Training 70 The Hon Warren Truss MP Covering the extensive services available in the Hunter Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development Innovation and Creativity 74 How the Hunter is growing it’s reputation as a centre of innovation and creativity Living in the Hunter 79 STATE GOVERNMENT Community and lifestyle in the Hunter The Hunter is the biggest contributor to the NSW economy outside of Sydney and a jewel in NSW’s rich Business Organisations regional crown. -

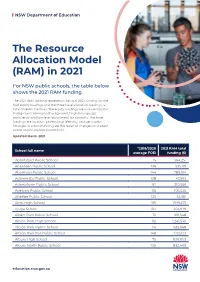

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Lambton Short-Takes

Lambton Short-Takes A welcoming school leading in excellence, innovation and opportunity Lambton High School T(02)49523977 F(02)49562429 E:[email protected] The week ahead TERM 2 WEEK 5A MONDAY 28 MAY □ Preliminary Assessment Period □ Yr 8 Technology Assessment Task Due - 8T5,8,9 □ Greenday Sponsorship excursion □ Psychology career discussion 2 pm TUESDAY 29 MAY □ Preliminary Assessment Period □ QTIP TRAINING □ Stage 5 Debating : Library : C Vodicar □ HSC English Adv and Stand Assessment Task p3 and 4 – MPC □ Greenday Sponsorship with students 12-3pm: C Hayden □ Bill Turner Girls : 12-3pm – B Donaghey MORE DISTINGUISHED YEARS OF SERVICE This week we once again recognise significant achievements WEDNESDAY 30 MAY and milestones of our teachers who also received certificates □ Preliminary Assessment Period from Mark Scott, Secretary of the Department of Education. Congratulations and thank you to Ms Glabus (20 Years), Ms □ Year 12 PLP Interviews Freer (20 years), Ms Sandland (20 years) and Ms Nowak (20 □ Starstruck Rehearsal Newcastle Entertainment Years). We thank them for their dedication to supporting our Centre A Grivas students and distinguished service to our community. □ Open Girls Hockey KO 1-3 pm : J Lawrence □ Aboriginal dance class : sport ConnectED Conference for NSW Public School □ PLCG 7.30am - 8.30am: M. Davies Principals On Thursday 24 and Friday 25 the Music Department represented our school by providing all the musical THURSDAY 31 MAY entertainment at the Principal's Conference at Crowne Plaza, □ Preliminary Assessment Period Pokolbin. A wonderful opportunity for our students to perform and be seen by all the Principals, Directors of Education and □ Yr 8 Technology Assessment Task Due - 8T4 Secretary, Mr. -

Orica Kooragang Island Remediation Program

23 February 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Orica Kooragang Island Remediation Program Submitted to: Sherree Woodroffe Orica Australia Pty Ltd 15 Greenleaf Road Kooragang Island, NSW 2034 Report Number. 1418917_063_R_Rev2(a) REPORT EIS | ORICA KOORAGANG ISLAND REMEDIATION PROGRAM STATEMENT OF VALIDITY Prepared under Part 4, Division 4.1 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 Environmental Impact Statement prepared by: Gavan Butterfield Name: Todd Robinson Address: 124 Pacific Highway St LEONARDS NSW 2065 New South Wales, Australia Orica Kooragang Island: Remediation Program – Environmental Impact In respect of: Statement Applicant name: Orica Australia Pty Ltd Proposed Development consent to implement remediation works required under development: Management Order 20131407 of the Contaminated Lands Management Act 1997. Partial Lot 2 and Partial Lot 3 in Deposited Plan (DP) 234288 To be developed within the local government area of Newcastle City Council. The opinions and declarations in this Environmental Impact Statement are based upon information obtained from the public domain and Orica Australia Pty Ltd in addition to representatives of Government agencies and specialist consultants. Land to be developed: Pursuant to clause 6(f), Part 3, Schedule 2 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Regulation 2000, it is declared that this Environmental Impact Statement: Has been prepared pursuant to Part 4, Division 4.1 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, and with regard to the form and content requirements of clause 6 and clause 7 of Schedule 2 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Regulation 2000, and the Declaration: Secretary’s Environmental Assessment Requirements (SSD 7831) dated 18 August 2016. Contains information relevant to the environmental assessment of the development that is accurate at the date of preparation; and Contains information that to the best of our knowledge is neither false nor misleading. -

Legislative Assembly

4438 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday 21 November 2006 ______ Mr Speaker (The Hon. John Joseph Aquilina) took the chair at 2.15 p.m. Mr Speaker offered the Prayer. Mr SPEAKER: I acknowledge the Gadigal clan of the Eora nation and its elders and thank them for their custodianship of country. DISTINGUISHED VISITORS Mr SPEAKER: I welcome to the public gallery His Excellency Mr Kabir, the High Commissioner of Bangladesh, and Mrs Kabir, and Mr Anthony Khouri, the Consul-General of Bangladesh, who are guests of the honourable m embers for Macquarie Fields. FIRE BANS Ministerial Statement Mr MORRIS IEMMA (Lakemba—Premier, Minister for State Development, and Minister for Citizenship) [2.17 p.m.]: Total fire bans are again in place across most of the State today as firefighters battle a number of bushfires in the Blue Mountains, the Hunter Valley, Forbes, Oberon and the South Coast. Hot, dry and windy conditions have resulted in very high to extreme fire danger in many districts. Emergency declarations have been made for a number of the fires now burning. About 900 volunteer firefighters from the Rural Fire Service have been deployed, along with their colleagues from New South Wales Fire Brigades, Forests NSW and the National Parks and Wildlife Service. I acknowledge the employers of all of our volunteers for their ongoing support in allowing them to leave their workplaces to protect the community. The most serious of the fires are those currently burning in the Blue Mountains, where firefighters have been battling two bushfires in the Grose Valley for the past nine days. -

Newcastle Relocation Guide

Newcastle Relocation Guide Welcome to Newcastle Newcastle Relocation Guide Contents Welcome to Newcastle ......................................................................................................2 Business in Newcastle ......................................................................................................2 Where to Live? ...................................................................................................................3 Renting.............................................................................................................................3 Buying ..............................................................................................................................3 Department of Fair Trading...............................................................................................3 Electoral Information.........................................................................................................3 Local Council .....................................................................................................................4 Rates...................................................................................................................................4 Council Offices ..................................................................................................................4 Waste Collection................................................................................................................5 Stormwater .........................................................................................................................5 -

Raymond Terrace Schools

Raymond Terrace Schools – Afternoon Services [Includes Hunter River High, Raymond Terrace Public, St Brigids Primary, Irrawang Public, Irrawang High & Grahamstown Public] Area Route Start Service Route Time All areas – students 135 3.18pm *Grahamstown Public School [Hastings Dr], R Benjamin Lee Dr, L Mount Hall Rd 3.20pm Irrawang High School [Mount Hall Rd], R CamBridge catch this 135 service, Ave, R Morton St, Irrawang Public School, R Roslyn St, R Mount Hall Rd/Irrawang St, St Brigids Primary School (bus stop at Community Hall), R then continue as per Glenelg St, L Sturgeon St, Raymond Terrace Public School (back gate), 3.30pm Raymond Terrace Shopping Centre Sturgeon St, R William St, R below Adelaide St, R Adelaide St roundaBout, R Elkin Ave, Hunter River High School (Bay 9), L Adelaide St, R Adelaide St roundaBout, cross Pacific Highway onto Masonite Rd, L CaBBage Tree Rd – continues as per below…… Salt Ash, BoBs Farm, L Nelson Bay Rd, Williamtown, Salt Ash, L Marsh Rd, 4.05pm L Nelson Bay Rd Anna Bay [At the last bus stop on Nelson Bay Rd before Port Stephens Dr [#231641], connect onto R131 for travel to Salamander Central, Corlette, Nelson Bay, Shoal Bay, Fingal Bay – see 131 Below] 4.20pm Anna Bay Shops [Bus continues as R130], R CampBell Ave/Margaret St/Fitzroy St, R Pacific Ave, L Ocean Ave, L Morna Point Rd, R Gan Gan Rd, L Frost Rd, R Nelson Bay Rd, L Salamander Way, R Bagnall Beach Rd, 4.40pm Salamander Central [Bus continues as R133 through to Galoola Dr Nelson Bay – See Below] [Passengers for Soldiers Point connect here -

NEWSLETTER Raymond Terrace Nsw 2324

RAYMOND TERRACE & DISTRICT HISTORICAL SOCIETY Inc RAYMOND TERRACE & DISTRICT HISTORICAL SOCIETY Inc. PO Box 255 NEWSLETTER Raymond Terrace nsw 2324 Patrons Bob Baldwin - MP Craig Baumann - MLA January–February–March 2010 Frank Terenzini MLA Sharon Grierson MP Volume Eleven Number One President Peter Francis Phone: 4987 3970 Linking yesterday with tomorrow Vice President Boris Sokoloff Phone: 4954 8976 Treasurer Anne Knott Phone: 4987 2645 Secretary Faye Clark Phone: 4987 6435 Minutes Secretary Vicki Saunderson Phone: 4987 7661 Research Officer Elaine Hall Phone: 4987 3477 Museum Curator Jean Spencer Phone: 4997 5327 Assistant Curator Sue Sokoloff Phone: 4954 8976 Newsletter Editor Helen James Phone: 4982 8067 COMMITTEE: David Gunter Laurel Young Moira Saunderson Every care is taken to check the accuracy of information printed but we cannot hold ourselves responsible for errors. Unless an article is marked © COPYRIGHT, Historical & Family History organizations have permission to reprint items from this Newsletter, although acknowledgement of author and source must be given. 2 Notes from the secretary – Faye Clark story of the Fiesta as told by the Manning family and visitors and workers to the Theatre is now completed. The opening event was Monday 30 November. The students ¾ The Working Bee which was held on Sunday 1 November, have worked very hard, being willing to take on any job achieved a lot, in a fairly short period of time. There were that they have been asked to do. A special thanks to Robyn many jobs that needed doing – the Cottage got a big spruce Cox and Ian Battle for leading the students through the up after the dust storms, and a lot of rubbish that had built project, and for continuing to encourage the students to do up around the grounds and in the gutters was removed. -

Boys 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

Teams - BOYS 1 BARRANJOEY HIGH SCHOOL 2 BARRANJOEY HIGH SCHOOL#2 3 BELMONT HIGH SCHOOL 4 CALLAGHAN COLLEGE 5 COFFS HARBOUR CHRISTIAN COMMUNITY SCHOOL 6 GOROKAN HIGH SCHOOL 7 GREAT LAKES COLLEGE FORSTER 8 GREAT LAKES COLLEGE FORSTER #2 9 GREAT LAKES COLLEGE FORSTER #3 10 HASTINGS SECONDARY COLLEGE - PORT MACQUARIE CAMPUS 11 ILLAWARRA SPORTS HIGH 12 KOTARA HIGH SCHOOL 13 LAKE MUNMORAH HIGH SCHOOL 14 LAKE MUNMORAH HIGH SCHOOL #2 15 LAKE MUNMORAH HIGH SCHOOL #3 16 LAMBTON HIGH SCHOOL 17 LAMBTON HIGH SCHOOL #2 18 MACKILLOP COLLEGE 19 MACKILLOP COLLEGE #2 20 MORISSET HIGH SCHOOL 21 NARRABEEN SPORTS HIGH SCHOOL 22 NARRABEEN SPORTS HIGH SCHOOL #2 23 NARRABEEN SPORTS HIGH SCHOOL #3 24 NARRABEEN SPORTS HIGH SCHOOL #4 25 NEWCASTE GRAMMAR SCHOOL 26 NEWCASTLE GRAMMAR SCHOOL#2 27 NEWCASTLE HIGH SCHOOL 28 NEWCASTLE HIGH SCHOOL #2 29 NEWCASTLE HIGH SCHOOL #3 30 NEWMAN SENIOR TECHNICAL COLLEGE 31 NEWMAN SENIOR TECHNICAL COLLEGE #2 32 NORTHERN BEACHES SECONDARY COLLEGE 33 NORTHERN BEACHES SECONDARY COLLEGE #2 34 NORTHERN BEACHES SECONDARY COLLEGE #3 35 SAN CLEMENTE MAYFIELD 36 ST FRANCIS XAVIER'S COLLEGE 37 ST FRANCIS XAVIER'S COLLEGE #2 38 ST FRANCIS XAVIER'S COLLEGE #3 39 ST FRANCIS XAVIER'S COLLEGE #4 40 ST MARYS GATESHEAD 41 ST MARYS GATESHEAD #2 42 ST MARYS GATESHEAD #3 43 ST MARYS GATESHEAD #4 44 ST MARYS GATESHEAD #5 45 ST PAULS CATHOLIC COLLEGE MANLY 46 ST PHILLIPS CHRISTIAN COLLEGE 47 ST PIUS X ADAMSTOWN 48 ST PIUS X ADAMSTOWN #2 49 SWANSEA HIGH SCHOOL 50 SWANSEA HIGH SCHOOL #2 51 SWANSEA HIGH SCHOOL #3 52 TUGGERAH LAKES SECONDARY COLLEGE: THE ENTRANCE CAMPUS 53 TUGGERAH LAKES SECONDARY COLLEGE TUMBI UMBI CAMPUS 54 TUGGERAH LAKES SECONDARY COLLEGE TUMBI UMBI CAMPUS #2 55 VANUATU TEAM OUTREACH 56 VANUATA TEAM PONGO 57 WADALBA COMMUNITY SCHOOL 58 WHITEBRIDGE HIGH 59 WHITEBRIDGE HIGH #2 60 WHITEBRIDGE HIGH #3 61 WHITEBRIDGE HIGH #4 62 WHITEBRIDGE HIGH #5 63 WHITEBRIDGE HIGH #6 64 WHITEBRIDGE HIGH #7 Please be at Bar Beach for a 7:30am start on Thursday 19th . -

Spring Edition – No: 48

Spring Edition – No: 48 2015 Commonwealth Vocational Education Scholarship 2015. I was awarded with the Premier Teaching Scholarship in Vocational Education and Training for 2015. The purpose of this study tour is to analyse and compare the Vocational Education and Training (Agriculture/Horticulture/Primary Industries) programs offered to school students in the USA in comparison to Australia and how these articulate or prepare students for post school vocational education and training. I will be travelling to the USA in January 2016 for five weeks. While there, I will visit schools, farms and also attend the Colorado Agriculture Teachers Conference on 29-30th January 2016. I am happy to send a detailed report of my experiences and share what I gained during this study tour with all Agriculture teachers out there. On the 29th of August I went to Sydney Parliament house where I was presented with an award by the Minister of Education Adrian Piccoli. Thanks Charlie James President: Justin Connors Manilla Central School Wilga Avenue Manilla NSW 2346 02 6785 1185 www.nswaat.org.au [email protected] ABN Number: 81 639 285 642 Secretary: Carl Chirgwin Griffith High School Coolah St, Griffith NSW 2680 02 6962 1711 [email protected]. au Treasurer: Membership List 2 Graham Quintal Great Plant Resources 6 16 Finlay Ave Beecroft NSW 2119 NSWAAT Spring Muster 7 0422 061 477 National Conference Info 9 [email protected] Articles 13 Technology & Communication: Valuable Info & Resources 17 Ian Baird Young NSW Upcoming Agricultural