Changing Minds Winning Peace a New Strategic Direction for U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fasig-Tipton

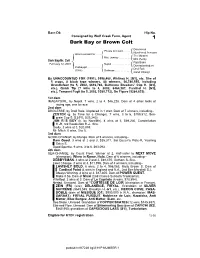

Barn D6 Hip No. Consigned by Wolf Creek Farm, Agent 1 Dark Bay or Brown Colt Damascus Private Account . { Numbered Account Unaccounted For . The Minstrel { Mrs. Jenney . { Mrs. Penny Dark Bay/Br. Colt . Raja Baba February 12, 2001 Nepal . { Dumtadumtadum {Imabaygirl . Droll Role (1988) { Drolesse . { Good Change By UNACCOUNTED FOR (1991), $998,468, Whitney H. [G1], etc. Sire of 5 crops, 8 black type winners, 88 winners, $6,780,555, including Grundlefoot (to 5, 2002, $616,780, Baltimore Breeders’ Cup H. [G3], etc.), Quick Tip (7 wins to 4, 2002, $464,387, Cardinal H. [G3], etc.), Tempest Fugit (to 5, 2002, $380,712), Go Figure ($284,633). 1st dam IMABAYGIRL, by Nepal. 7 wins, 2 to 4, $46,228. Dam of 4 other foals of racing age, one to race. 2nd dam DROLESSE, by Droll Role. Unplaced in 1 start. Dam of 7 winners, including-- ZESTER (g. by Time for a Change). 7 wins, 3 to 6, $199,512, Sea- gram Cup S. [L] (FE, $39,240). JAN R.’S BOY (c. by Norcliffe). 4 wins at 3, $69,230, Constellation H.-R, 3rd Resolution H.-L. Sire. Drolly. 2 wins at 3, $20,098. Mr. Mitch. 6 wins, 3 to 5. 3rd dam GOOD CHANGE, by Mongo. Dam of 5 winners, including-- Ram Good. 3 wins at 2 and 3, $35,317, 3rd Queen’s Plate-R, Yearling Sales S. Good Sparkle. 9 wins, 3 to 6, $63,093. 4th dam SEA-CHANGE, by Count Fleet. Winner at 2. Half-sister to NEXT MOVE (champion), When in Rome, Hula. -

The Crux of the Hindu and PIB Vol 33

News for May 2017 aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 33 NewsVol. and 33 Events of May 2017 aspirantforum.com Vol. 33 May 2017 33 May Vol. Visit Aspirantforum.com for guidance and study material for IAS Exam. aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 33 News and Events of May 2017 Aspirant Forum is a Community for the UPSC Contents Civil Services (IAS) Aspirants, to discuss and debate the various things related to the exam. We welcome an active National News.............4 participation from the fellow members to enrich the knowledge of all. Economy News..........16 Editorial Team: PIB Compilation: Nikhil Gupta International News....32 The Hindu Compilation: Shakeel Anwar India and the World..35 Ranjan Kumar Shahid Sarwar Karuna Thakur Science and Technology + Designed by: Anupam Rastogi Environment..............43 The Crux will be published online Miscellaneous News and for free on 10th of every month. We appreciate the friends and Events.........................75 followers for apprepreciating our effort. For any queries, guidance needs and support, Please contact at: [email protected] You may also follow our website Aspirantforum.com for free on- line coaching and guidanceforIASaspirantforum.com Vol. 33 May 2017 33 May Vol. Visit Aspirantforum.com for guidance and study material for IAS Exam. aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 33 News and Events of May 2017 About the ‘CRUX’ Introducing a new and convenient product, to help the aspirants for the various public services examina- tions. The knowledge of the Current Affairs constitute an indispensable tool for all the recruitment examinations today.However, an aspirant often finds it difficult to read and memorize all the current affairs, from an exam perspective.The Newspapers and magazines are full of information, that may or may not be useful for the exams. -

Universal Periodic Review 2009

UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW 2009 SAUDI ARABIA NGO: European Centre for Law and Justice 4, Quai Koch 67000 Strasbourg France RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN THE SAUDI ARABIA SECTION 1: Legal Framework I. Saudi Constitutional Provisions Saudi Arabia is an Islamic monarchy.1 The Saudi Constitution is comprised of the Koran, Sharia law, and the Basic Law.2 “Islamic law forms the basis for the country’s legal code.”3 Strict Islamic law governs,4 and as such, the Saudi Constitution does not permit religious freedom. Even the practice of Islam itself is limited to the strict, Saudi-specific interpretation of Islam.5 Importantly, the Saudi government makes essentially no distinction between religion and government.6 According to its constitution, Saudi Arabia is a monarchy with a limited Consultative Council and Council of Ministers.7 The Consultative Council is governed by the Shura Council Law, which is based on Islam,8 and serves as an advisory body that operates strictly within the traditional confines of Islamic law.9 The Council of Ministers, expressly recognized by the Basic Law,10 is authorized to “examine almost any matter in the kingdom.”11 The Basic Law was promulgated by the king in 1993 and operates somewhat like a limited “bill of rights” for Saudi citizens. Comprising a portion of the Saudi Constitution, the Basic Law broadly outlines “the government’s rights and responsibilities,” as well as the general structure of government and the general source of law (the Koran). 12 The Basic Law consists of 83 articles defining the strict, Saudi Islamic state. By declaring that Saudi Arabia is an Islamic state and by failing to make any 1 U.S. -

Significant New Biostratigraphic Horizons in the Qusaiba Member of the Silurian Qalibah Formation of Central Saudi Arabia, and T

GeoArabia, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2005 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Significant new biostratigraphic horizons in the Qusaiba Member of the Silurian Qalibah Formation of central Saudi Arabia, and their sedimentologic expression in a sequence stratigraphic context Merrell A. Miller and John Melvin ABSTRACT Detailed analysis of over 1,000 subsurface Silurian palynology samples from 34 wells has allowed the development of a robust biostratigraphy based on acritarchs, chitinozoans and cryptospores for the Qusaiba Member of the Qalibah Formation, central Saudi Arabia. The new index fossils described herein augment the Arabian Plate Silurian chitinozoan zonation. The high-resolution biostratigraphic zonation consists of nine First Downhole Occurrences (FDOs) from the lower Telychian through Aeronian. In particular, three regionally recognizable palynologic horizons were identified within the lower part of the informally designated Mid-Qusaiba Sandstone (Angochitina hemeri Interval Zone), and above the FDO of Sphaerochitina solutidina. This high level of biostratigraphic resolution provides a framework for the integration of the sedimentology and calibration with global sea level curves, leading to a detailed understanding of the sequence stratigraphic evolution of this part of the Silurian in Saudi Arabia. Sedimentological core studies identify three Depositional Facies Associations (DFAs) within the Mid-Qusaiba Sandstone interval, including: (1) shelfal deposits (DFA-I) characterized by interbedded hummocky cross-stratified sandstones, graded siltstones and bioturbated mudstones; (2) turbiditic deposits (DFA-II); and (3) an association of heavily contorted and re- sedimented sandstones, siltstones and mudstones (DFA-III) that is considered representative of oversteepened slopes upon the Qusaiba shelf. Integration of the newly recognized palynostratigraphic horizons and the sedimentological data facilitates an understanding of the sequence stratigraphic evolution of the Mid-Qusaiba Sandstone interval and its immediate precursors. -

Download This Report

Human Rights Watch July 2004 Vol. 16, No. 5(E) Bad Dreams: Exploitation and Abuse of Migrant Workers in Saudi Arabia SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................... 1 METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................................6 KEY RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................ 8 I. MIGRANT COMMUNITIES IN SAUDI ARABIA......................................................11 II. THE FOREIGN LABOR SPONSORSHIP SYSTEM AND ITS ABUSES.............19 Workers’ Contracts and Wages: False Promises ................................................................20 Job Substitution.......................................................................................................................22 “Free Visa” Illusions ..............................................................................................................25 III. VULNERABILITY AND EXPLOITATION...............................................................27 Official Documents: Consequences of Illegal Employer Practices.................................29 Fear of Arrest and Deportation............................................................................................32 No Access to Medical Care ...................................................................................................33 Long Working Hours without Overtime Pay.....................................................................36 -

Rattigan V. Holder

Case 1:04-cv-02009-ESH-JMF Document 110 Filed 07/30/09 Page 1 of 1 Case 1:04-cv-02009-ESH-JMF Document 6 Filed 01/27/05 Page 1 of 40 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ---------------------------------------------------------------------- x WILFRED SAMUEL RATTIGAN, x Plaintiff, x 1:04 CV 02009 (ESH) -against- x FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT JOHN ASHCROFT, Attorney General, United x States Department of Justice; JURY TRIAL x DEMANDED Defendant.. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- x PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1. This is a civil action in which the plaintiff, WILFRED SAMUEL RATTIGAN (hereinafter referred to as “Rattigan”or “Plaintiff”), a current employee of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (hereinafter referred to as the “FBI” or the “Bureau”), seeks relief for violations of his rights secured by Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq., as a result of discrimination in the terms and conditions of his employment by the FBI on the basis of his race, national origin and religion, and for retaliation for complaints he has made about his treatment. The plaintiff seeks damages, both compensatory and punitive, affirmative and equitable relief, an award of costs and attorneys fee, and such other and further relief, as this Court deems just and equitable. JURISDICTION 2. Jurisdiction is conferred upon this Court by 28 U.S.C. §§1331, 1343(3), this being an action seeking redress for violation of the plaintiff’s constitutional and civil rights. 3. Plaintiff’s claim for declaratory and injunctive relief is authorized by 28 U.S.C. §2201 and 2202 and Rule 57 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. -

The Atomic Terrorist: Assessing the Likelihood

THE ATOMIC TERRORIST: ASSESSING THE LIKELIHOOD John Mueller Department of Political Science Ohio State University January 1, 2008 Mershon Center 1501 Neil Avenue Columbus, OH 43201-2602 614-247-6007 614-292-2407 (fax) [email protected] http://polisci.osu.edu/faculty/jmueller Prepared for presentation at the Program on International Security Policy, University of Chicago, January 15, 2008 ABSTRACT: A terrorist atomic bomb is commonly held to be the single most serious threat to the national security of the United States. Assessed in appropriate context, that could actually be seen to be a rather cheering conclusion because the likelihood that a terrorist group will come up with an atomic bomb seems to be vanishingly small. Moreover, the degree to which al-Qaeda--the chief demon group and one of the few terrorist groups to see value in striking the United States--has sought, or is capable of, obtaining such a weapon seems to have been substantially exaggerated. When asked by Jim Lehrer in their first presidential debate in September 2004 to designate the "single most serious threat to the national security to the United States," the candidates had no difficulty agreeing on one. Concluded Lehrer, "So it's correct to say the single most serious threat you believe, both of you believe, is nuclear proliferation?" George W. Bush: "In the hands of a terrorist enemy." John Kerry: "Weapons of mass destruction, nuclear proliferation."1 In like manner, Governor Thomas Kean, chair of the 9/11 Commission, confesses that what keeps him up at night is "the -

To What Extent Would E-Mall Enable Smes to Adopt E-Commerce?

International Journal of Business and Management; Vol. 7, No. 22; 2012 ISSN 1833-3850 E-ISSN 1833-8119 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education To What Extent Would E-mall Enable SMEs to Adopt E-Commerce? Adel A. Bahaddad1,2, Rayed AlGhamdi2 & Luke Houghton3 1 Information and Communication School, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia 2 Faculty of Computing & IT, King AbdulAziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 3 Business School, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia Correspondence: Adel A. Bahaddad, Institute of Integrated and Intelligent Systems, Griffith University, Brisbane, Room 1.45-N34, 170 Kessels Road, Nathan Qld 4111, Australia. Tel: 61-737-353-765. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 18, 2012 Accepted: October 9, 2012 Online Published: October 29, 2012 doi:10.5539/ijbm.v7n22p123 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v7n22p123 Abstract This paper presents findings from a study of e-commerce adoption by Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Saudi Arabia. Only tiny number of Saudi commercial organizations, mostly medium and large companies from the manufacturing sector, in involved in e-commerce implementation. The latest report released in 2010 by The Communications and Information Technology Commission (CITC) in Saudi Arabia shows that only 8% of businesses sell online. Accordingly new research has been conducted to explore to what extent electronic mall (e-mall) would enable SMEs in Saudi Arabia to adopt and use online channels for their sales. A quantitative analysis of responses obtained from a survey of 108 SMEs in Saudi Arabia was conducted. The main results of the current analysis demonstrate the significant of organizational factors, and technology and environmental factors. -

Predicting Tobacco Use Among High School Students by Using the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

[Downloaded free from http://www.thoracicmedicine.org on Thursday, September 06, 2012, IP: 41.233.135.148] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Original Article Predicting tobacco use among high school students by using the global youth tobacco survey in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Mohamed S. Al Moamary, Mohammed O. Al Ghobain, Sulieman N. Al Shehri1, Ahmed Y. Gasmelseed2, Mohamed S. Al-Hajjaj3 College of Medicine, Abstract: King Saud bin OBJECTIVE: To identify the predictors that lead to cigarette smoking among high school students by utilizing the Abdulaziz University global youth tobacco survey in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). for Health Sciences, METHODS: A cross‑sectional study was conducted among high school students (grades 10–12) in Riyadh, KSA, 1School Health between April 24, 2010, and June 16, 2010. Department, Ministry RESULTS: The response rate of the students was 92.17%. The percentage of high school students who had previously of Education, 2King smoked cigarettes, even just 1–2 puffs, was 43.3% overall. This behavior was more common among male students Abdullah International (56.4%) than females (31.3%). The prevalence of students who reported that they are currently smoking at least Center for Medical one cigarette in the past 30 days was 19.5% (31.3% and 8.9% for males and females, respectively). “Ever smoked” Research, 3College of status was associated with male gender (OR = 2.88, confidence interval [CI]: 2.28–3.63), parent smoking (OR = 1.70, Medicine, King Saud CI: 1.25–2.30) or other member of the household smoking (OR = 2.11, CI: 1.59–2.81) who smoked, closest friends who smoked (OR = 8.17, CI: 5.56–12.00), and lack of refusal to sell cigarettes (OR = 5.68, CI: 2.09–15.48). -

To First Dams Name Hip No

Index to First Dams Name Hip No. Name Hip No. A. Acadia .........................................413. Blue Sky Princess.......................143. Aces.............................................124. Blushing Ogygian.......................144. A Chance of Storm.....................414. Bolshoi Comedy .........................145. Adel .............................................415. Bonnie's Poker ............................146. A Dream Above ..........................416. Bonzo's Baby..............................147. Agenda........................................417. Bosra Sham ................................444. Agotaras......................................418. Bought Twice ..............................445. Ailsa .............................................125. Bound ..........................................148. Al Balessa ...................................419. Bounteous (IRE)..........................446. Alchaasibiyeh..............................126. Brave Hearted (GB) ...................447. Alleged Thoughts .......................420. Brave Raj.....................................448. All the Crown...............................127. Briarcliff........................................149. Allusion ........................................128. Bridal Tea ....................................449. American Tango..........................129. Bright Feather .............................150. Am Sensational...........................421. Broadcast....................................151. Andestine ....................................130. -

Naseem A. Qureshi, M.D., Ph.D

Naseem A. Qureshi, M.D., Ph.D. Consultant Psychiatrist and Head of Research Unit Administration for Mental Health and Social Services Ministry of Health Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Summary 1. Professional Qualification: MBBS (India), MD (India), PhD (Erasmus University, the Netherlands, 2005) 2. Clinical Experience: total 25 years, -1980-1983 in India, Scientific Research Officer, -Dec. 1983-April 2005 in Saudi Arabia, Psychiatric Specialist plus 10 years administrative experience as Medical Director, Buraidah Mental Health Hospital, Al- Qaseem Region, Saudi Arabia (total 21 years in KSA), which has 150-Bed capacity. 3. Specialist Senior Registrar, Rashid Hospital, 1 June 2005-28 Feb. 2006, Dubai, UAE. 4. Publsihed papers more than 120 in national and international journals 5. 12 e-Letters publsihed in British J Psychiatry Online 6. 5 eletters published in spiked.central online 7. 150 Rapid Responses published in bmj.com. responses 1 8. Consultant Reviewer for more than 5 Saudi scientific medical journals, EMHJ (WHO) and KACST, and international J - Dove Medical Press, J Sexual Medicine, J Hospital Administration. 9. Post-Graduate Course in Torture Medicine 10. Special areas of interest: *CME and Research, *Primary care and Interdepartmental Liaison services, *Quality Assurance Programs, *Teaching basic sciences including biostatistics, psychology, communication skills, epidemiology, and sociobiology to medical students, *Delivery of excellent psychiatric services to patients of all age bands *Planning innovative educational programs, their implementation and subsequent evaluation. 11. More than 20 years’ working experience as Director, CME and Research, Buraidah Mental Health Hospital, Al-Qassim Region, KSA 12. Liaison Consultant for Primary Care Psychiatric Services, Al-Qassim Region, KSA 1990-2005. -

Intelligence Community Assessment ICA2003-03, Regional Consequences of Regime Change in Iraq, January 2003

Description of document: National Intelligence Council (NIC), Intelligence Community Assessment ICA2003-03, Regional Consequences of Regime Change in Iraq, January 2003 Requested date: 26-December-2010 Released date: 18-February-2011 Posted date: 14-March-2011 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, D.C. 20505 Fax: (703)613-3007 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Central Intelligence Agency Washington. D.C. 20505 18 February 2011 Reference: F-2011-00576 This is a final response to your 26 December 2010 Freedom oflnfonnation Act (FOIA) request for a copy of the intelligence assessment written by Paul Pillar two months before the U.S.