Earl Kemp: Ei46

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Subculture Identification: Training Counselors to Work with Gay Men

Article 22 Gay Subculture Identification: Training Counselors to Work With Gay Men Justin L. Maki Maki, Justin L., is a counselor education doctoral student at Auburn University. His research interests include counselor preparation and issues related to social justice and advocacy. Abstract Providing counseling services to gay men is considered an ethical practice in professional counseling. With the recent changes in the Defense of Marriage Act and legalization of gay marriage nationwide, it is safe to say that many Americans are more accepting of same-sex relationships than in the past. However, although societal attitudes are shifting towards affirmation of gay rights, division and discrimination, masculinity shaming, and within-group labeling between gay men has become more prevalent. To this point, gay men have been viewed as a homogeneous population, when the reality is that there are a variety of gay subcultures and significant differences between them. Knowledge of these subcultures benefits those in and out-of-group when they are recognized and understood. With an increase in gay men identifying with a subculture within the gay community, counselors need to be cognizant of these subcultures in their efforts to help gay men self-identify. An explanation of various gay male subcultures is provided for counselors, counseling supervisors, and counselor educators. Keywords: gay men, subculture, within-group discrimination, masculinity, labeling Providing professional counseling services and educating counselors-in-training to work with gay men is a fundamental responsibility of the counseling profession (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014). Although not all gay men utilizing counseling services are seeking services for problems relating to their sexual orientation identification (Liszcz & Yarhouse, 2005), it is important that counselors are educated on the ways in which gay men identify themselves and other gay men within their own community. -

March 2013 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle March 2013 Te Next NASFA Meetng is Saturday 16 March 2013 at te Regular Locaton ConCom Meeting 16 March, 3P; see below for details Member of MindGear LLC <mindgearlabs.com>, discussing d Oyez, Oyez d 3D printers. (And doubtless he’ll touch on some of the other cool stuff in their lab.) The next NASFA Meeting will be at 6P, Saturday 16 MARCH ATMM March 2013 at the regular meeting location—the Madison The host and location for the March After-the-Meeting Meet- campus of Willowbrook Baptist Church (old Wilson Lumber ing are undetermined at press time, though there’s a good Company building) at 7105 Highway 72W (aka University chance it will be at the church. The usual rules apply—that is, Drive). Please see the map below if you need help finding it. please bring food to share and your favorite drink. MARCH PROGRAM Also, assuming it is at the church, please stay to help clean The March program will be Rob Adams, the Managing up. We need to be good guests and leave things at least as clean as we found them. CONCOM MEETINGS The next Con†Stellation XXXII concom meeting will be 3P Saturday 16 March 2013—the same day as the club meeting. Jeff Road Jeff Kroger At press time the plan is to meet at the church, but that’s subject to confirmation that the building will be available at that time. US 72W Please stay tuned to email, etc., for possible updates. (aka University Drive) CHANGING SHUTTLE DEADLINES The latest tweak to the NASFA Shuttle schedule shifted the usual repro date somewhat to the right (roughly the weekend before each meeting) but much of each issue will need to be Slaughter Road Slaughter put to bed as much as two weeks before the monthly meeting. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

Logging Into Horror's Closet

Logging into Horror’s Closet: Gay Fans, the Horror Film and Online Culture Adam Christopher Scales Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies September 2015 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract Harry Benshoff has boldly proclaimed that ‘horror stories and monster movies, perhaps more than any other genre, actively invoke queer readings’ (1997, p. 6). For Benshoff, gay audiences have forged cultural identifications with the counter-hegemonic figure of the ‘monster queer’ who disrupts the heterosexual status quo. However, beyond identification with the monstrous outsider, there is at present little understanding of the interpretations that gay fans mobilise around different forms and features of horror and the cultural connections they establish with other horror fans online. In addressing this gap, this thesis employs a multi-sited netnographic method to study gay horror fandom. This holistic approach seeks to investigate spaces created by and for gay horror fans, in addition to their presence on a mainstream horror site and a gay online forum. In doing so, this study argues that gay fans forge deep emotional connections with horror that links particular textual features to the construction and articulation of their sexual and fannish identities. In developing the concept of ‘emotional capital’ that establishes intersubjective recognition between gay fans, this thesis argues that this capital is destabilised in much larger spaces of fandom where gay fans perform the successful ‘doing of being’ a horror fan (Hills, 2005). -

GLBT Historical Society Archives

GLBT Historical Society Archives - Periodicals List- Updated 01/2019 Title Alternate Title Subtitle Organization Holdings 1/10/2009 1*10 #1 (1991) - #13 (1993); Dec 1, Dec 29 (1993) 55407 Vol. 1, Series #2 (1995) incl. letter from publisher @ditup #6-8 (n.d.) vol. 1 issue 1 (Win 1992) - issue 8 (June 1994 [2 issues, diff covers]) - vol. 3 issue 15 10 Percent (July/Aug 1995) #2 (Feb 1965) - #4 (Jun 1965); #7 (Dec 1965); #3 (Winter 1966) - #4 (Summer); #10 (June 1966); #5 (Summer 1967) - #6 (Fall 1967); #13 (July 1967); Spring, 1968 some issues incl. 101 Boys Art Quarterly Guild Book Service and 101 Book Sales bulletins A Literary Magazine Publishing Women Whoever We Choose 13th Moon Thirteenth Moon To Be Vol. 3 #2 (1977) 17 P.H. fetish 'zine about male legs and feet #1 (Summer 1998) 2 Cents #4 2% Homogenized The Journal of Sex, Politics, and Dairy Products One issue (n.d.) 24-7: Notes From the Inside Commemorating Stonewall 1969-1994 issue #5 (1994) 3 in a Bed A Night in the Life 1 3 Keller Three Keller Le mensuel de Centre gai&lesbien #35 (Feb 1998), #37 (Apr 1998), #38 (May 1998), #48 (May 1999), #49 (Jun 1999) 3,000 Eyes Are Watching Me #1 (1992) 50/50 #1-#4 (June-1995-June 1996) 6010 Magazine Gay Association of Southern Africa (GASA) #2 (Jul 1987) - #3 (Aug 1987) 88 Chins #1 (Oct 1992) - #2 (Nov 1992) A Different Beat An Idea Whose Time Has Come... #1 (June 3, 1976) - #14 (Aug 1977) A Gay Dragonoid Sex Manual and Sketchbook|Gay Dragonoind Sex A Gallery of Bisexual and Hermaphrodite Love Starring the A Dragonoid Sex Manual Manual|Aqwatru' & Kaninor Dragonoid Aliens of the Polymarinus Star System vol 1 (Dec 1991); vol. -

Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China

Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China by Gang Pan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Gang Pan 2015 Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China Gang Pan Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This dissertation concerns itself with the eruption of a large number of gay narratives on the Chinese internet in its first decade. There are two central arguments. First, the composing and sharing of narratives online played the role of a social movement that led to the formation of gay identity and collectivity in a society where open challenges to the authorities were minimal. Four factors, 1) the primacy of the internet, 2) the vernacular as an avenue of creativity and interpretation, 3) the transitional experience of the generation of the internet, and 4) the evolution of gay narratives, catalyzed by the internet, enhanced, amplified, and interacted with each other in a highly complicated and accelerated dynamic, engendered a virtual gay social movement. Second, many online gay narratives fall into what I term “prodigal romance,” which depicts gay love as parent-obligated sons in love with each other, weaving in violent conflicts between desire and duty in its indigenous context. The prodigal part of this model invokes the archetype of the Chinese prodigal, who can only return home having excelled and with the triumph of his journey. -

Sept1998 (Without Graphics)

PO Box 656, Washington, DC 20044 - (202) 232-3141 - Issue #102 - Sept. 1998 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://members.aol.com/lambdasf/home.html Gaylaxicon 1999 “Video Madness” Party Gayteways Is Completed - Con Committee Meeting Set for Sept. 19th Finally! announced by Rob Gates (New Location, reported by Rob Gates Same Old Madness) GAYLAXICON 1999: THE 10TH GAYLAXICON After almost two years, it’s fin- That’s right, gang, it’s time for ished! Gayteways is Lambda Sci-Fi’s first another bout of “video madness”! It’s set foray into ‘zine publishing. It’s been a for Saturday, Sept. 19th - beginning at 3:00 long time coming; but the finished prod- The Gaylaxicon 1999 ConComm PM and lasting until ??? However, the uct is fabulous. It includes original fiction, will hold its next meeting on Saturday, latest outbreak of this dreaded mania is poetry, and artwork submitted by LSFers, Sept. 12th, beginning at 4:00 PM. All are scheduled for a brand-new location: the Gaylactic Network members, and others. welcome. The meeting will be held at the home of LSFer Bethany Ramirez in Takoma As a reminder, our premise was home of LSFers Nan & Kay. There will be Park, MD! to put together a collection of quality, a BBQ grill out on the patio - so BYOG Other than the new site, the rest gay-positive, non-slash, non-porn, genre (bring your own grillables) - and the usual of the “rules” remain the same. As with works. The idea was originally put for- munchies and soda. previous Lambda Sci-Fi “Video Madness” ward by Philip Wright and myself in 1996. -

Between Boys: Fantasy of Male Homosexuality in Boys' Love, Mary Renault, and Marguerite Yourcenar by Jui-An Chou Graduate Pr

Between Boys: Fantasy of Male Homosexuality in Boys’ Love, Mary Renault, and Marguerite Yourcenar by Jui-an Chou Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Anne F. Garréta, Supervisor, Chair ___________________________ Robyn Wiegman, Co-Chair ___________________________ Rey Chow ___________________________ Anne Allison Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Between Boys: Fantasy of Male Homosexuality in Boys’ Love, Mary Renault, and Marguerite Yourcenar by Jui-an Chou Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Anne F. Garréta, Supervisor, Chair ___________________________ Robyn Wiegman, Co-Chair ___________________________ Rey Chow ___________________________ Anne Allison An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Jui-an Chou 2018 Abstract “Between Boys: Fantasy of Male Homosexuality in Boys’ Love, Mary Renault, and Marguerite Yourcenar” examines an unexpected kinship between Boys’ Love, a Japanese male-on-male romance genre, and literary works by Mary Renault and Marguerite Yourcenar, two mid-twentieth century authors who wrote about male homosexuality. Following Eve Sedgwick, who proposed that a “rich tradition of cross- gender inventions of homosexuality” should be studied separately from gay and lesbian literature, this dissertation examines male homoerotic fictions authored by women. These fictions foreground a disjunction between authorial and textual identities in gender and sexuality, and they have often been accused of inauthenticity, appropriation, and exploitation. -

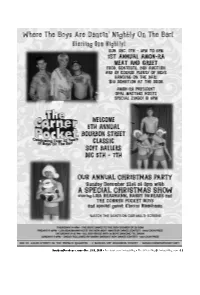

Southerndecadence.Com • Dec. 2-15, 2014 • Facebook.Com

SouthernDecadence.com • Dec. 2-15, 2014 • Facebook.com/AmbushMag • The Official Mag©: AmbushMag.com • 11 chocolate mint chip ice cream was so big, show featuring Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, that a table of six could not put a dent into Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins. I followed book review it. After dinner we explored the Quad area the show up with a quick dinner at Carnegie and enjoyed the live entertainers, my favor- Deli at The Mirage, just like I remember it in ite was the hot cowboys and Chippendale New York. Wolf at the Door, The Third Buddha, A Gathering Storm Dancers you could pose with for pictures. I finished the evening at one of the final What Comes Around, The Forever Mara- by Frank Perez Good lord, they have everything there. private parties at the Drais Nightclub and thon, and A Gathering Storm; and four Email: [email protected] I came back to the hotel and the bar Beach Club at the Cromwell Hotel. I have collections of short fiction: Dancing on the Jameson Currier. A Gathering Storm. inside the Mirage, Revolution was having no other word to describe this place than Moon; Desire, Lust, Passion, Sex; Still Chelsea Station Editions, 2014. ISBN: Gay Night entitled Revo Sunday. Seems sexy. I mean this club is like you have seen Dancing: New and Selected Stories; and 978-1-937627-20-1. 354 pages. $20.00. the gay scene shifts from club to club on the in the movies. You take an elevator up to the The Haunted Heart and Other Tales, Although A Gathering Storm is strip depending on the night of the week space and enter in the nightclub area. -

SCB Distributors Spring 2013 Catalog

SCB DISTRIBUTORS SPRING 2013 SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT SCB DISTRIBUTORS IS Birch Bench Press PROUD TO INTRODUCE Bongout Cassowary Press Coffee Table Comics Déjà vu Lifestyle Creations Grapevine Press Honest Publishing Penny-Ante Editions SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT The cover image is from page 113 of The Swan, published by Merlin Unwin, found on page 83 of this catalog. Catalog layout by Dan Nolte, based on an original design by Rama Crouch-Wong My First Kafka Runaways, Rodents, & Giant Bugs By Matthue Roth Illustrated by Rohan Daniel Eason “Matthue Roth is the kind of person you move to San Francisco to meet.” – Kirk Read, How I Learned to Snap An adaptation of 3 Kafka stories into startling, creepy, fun stories for all ages, featuring: ■ runaway children who meet up with monsters ■ a giant talking bug ■ a secret world of mouse-people This subversive debut takes a place alongside Sendak, Gorey, and Lemony Snicket. ■ endorsed by Neil Gaiman Matthue Roth wrote Yom Kippur a Go-Go and Never Mind the Goldbergs, nominated as an ALA Best Book and named a Best Book by the NY Public Library. He produced the animated series G-dcast, and wrote the feature film 1/20. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, the chef KAFKA, REIMAGINED AND ILLUSTRATED Itta Roth. www.matthue.com Rohan Daniel Eason, who studied painting in London, illustrated Anna and the Witch's Bottle and Tancredi. My First Kafka ISBN: 978-1-935548-25-6 $18.95 | hardcover 8 x 10 32 pages 32 B&W Illustrations Ages 7 & Up June Children’s Picture Book Literature ONE PEACE BOOKS SCB DISTRIBUTORS..|..SPRING 2013..|..1 Terminal Atrocity Zone: Ballard J.G. -

Gay and Lesbian Literature in the Classroom: Can Gay Themes Overcome Heteronormativity?

Journal of Praxis in Multicultural Education University of North Texas University of North Texas Journal of Praxis in Multicultural Education Sanders and Mathis: Can Gay Themes Overcome Heteronormativity? Historically, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) characters did not exist in the texts read and discussed in classrooms. One reason for the lack of classroom exposure to literature with homosexual themes could be contributed to avid censorship of such books. Daddy’s Roommate (1990) by Michael Willhoite was the second most banned/challenged book between 1990-2000, and Heather has Two Mommies (1990) by Leslea Newman ranked ninth as being the most banned/challenged in that decade. During the next decade both titles were not as fiercely contested. Willhoite and Newman’s book did not appear on the list of the 100 most banned/challenged books; And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell was the only book in the top ten contested books with gay and lesbian themes. Even though censorship continues to occur with LGBT books published for children, the books are not listed in the top ten censored books as often as a decade earlier. In order to fight censorship and prejudice surrounding LGBT literature, young readers as well as teachers and parents must learn how to transform their views of LGBT people. Educational organizations have realized the need for such a change in the classroom and have made a call for action; the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) passed a resolution (2007) calling for inclusion of LGBT issues in the classroom in addition to providing guidelines for training teachers on such inclusions. -

PDF EPUB} a Werewolf for Christmas by Sedonia Guillone a Werewolf for Christmas by Sedonia Guillone

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} A Werewolf for Christmas by Sedonia Guillone A Werewolf for Christmas by Sedonia Guillone. The Winner of the 2007 Gaylactic Spectrum Award for Best Novel was announced at Gaylaxicon 2007 on October 6th, along with a Short List of Recommended Works. Short Fiction and Other Work winners were announced early in 2008. Following are the Winner, Short List Works, and Other Nominees for each category for the 2007 Gaylactic Spectrum Awards. A handout listing the winners, short list recommendations, ISBN numbers, publishers, and a short writeup of each winner/short list item is available here. 2007 Best Novel Winner & Short List. WINNER: Vellum - Hal Duncan (Del Rey) SHORT LIST: Carnival - Elizabeth Bear (Bantam) Dragon's Teeth - James Hetley (Ace) The Growing - Susanne M. Beck & Okasha Skat'si (P.D. Publishing) The Privilege Of The Sword - Ellen Kushner (Bantam Spectra) Smoke and Ashes - Tanya Huff (DAW) Snow - Wheeler Scott (Torquere) Spin Control - Chris Moriarty (Bantam Spectra) The Virtu - Sarah Monette (Ace) 2007 Best Short Fiction Winners & Short List. WINNER: (TIE) In the Quake Zone - David Gerrold (Down These Dark Spaceways - SFBC) (TIE) Instinct - Joy Parks (The Future Is Queer - Arsenal Pulp) (TIE) The Language of Moths - Christopher Barzak (Realms of Fantasy) SHORT LIST: The Beatrix Gates - Rachel Pollack (The Future Is Queer - Arsenal Pulp) Bones Like Black Sugar - Catherynne M Valente (Fantasy magazine - Prime) The Captive Girl - Jennifer Pelland (Helix SF) Caught by Skin - Steve Berman (Sex in the System - Thunder's