Stephen Snoddy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1993

THE CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY The Annual General Meeting of the Contemporary Art Society will be held on Wednesday 7 September, 1994 at ITN, 200 Gray's Inn Road, London wcix 8xz, at 6.30pm. Agenda 1. To receive and adopt the report of the committee and the accounts for the year ended 31 December 1993, together with the auditors' report. 2. To reappoint Neville Russell as auditors of the Society in accordance with section 384 (1) of the Companies Act 1985 and to authorise the committee to determine their remunera tion for the coming year. 3. To elect to the committee Robert Hopper and Jim Moyes who have been duly nominated. The retiring members are Penelope Govett and Christina Smith. In addition Marina Vaizey and Julian Treuherz have tendered their resignation. 4. Any other business. By order of the committee GEORGE YATES-MERCER Company Secretary 15 August 1994 Company Limited by Guarantee, Registered in London N0.255486, Charities Registration No.2081 y8 The Contemporary Art Society Annual Report & Accounts 1993 PATRON I • REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother PRESIDENT Nancy Balfour OBE The Committee present their report and the financial of activities and the year end financial position were VICE PRESIDENTS statements for the year ended 31 December 1993. satisfactory and the Committee expect that the present The Lord Croft level of activity will be sustained for the foreseeable future. Edward Dawe STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE'S RESPONSIBILITIES Caryl Hubbard CBE Company law requires the committee to prepare financial RESULTS The Lord McAlpine of West Green statements for each financial year which give a true and The results of the Society for the year ended The Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover KG fair view of the state of affairs of the company and of the 31 December 1993 are set out in the financial statements on Pauline Vogelpoel MBE profit or loss of the company for that period. -

Conrad Shawcross

CONRAD SHAWCROSS Born 1977 in London, UK Lives and works in London, UK Education 2001 MFA, Slade School of Art, University College, London, UK 1999 BA (Hons), Fine Art, Ruskin School of Art, Oxford, UK 1996 Foundation, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK Permanent Commissions 2022 Manifold 5:4, Crossrail Art Programme, Liverpool Street station, Elizabeth line, London, UK 2020 Schism Pavilion, Château la Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, France Pioneering Places, Ramsgate Royal Harbour, Ramsgate, UK 2019 Bicameral, Chelsea Barracks, curated by Futurecity, London, UK 2018 Exploded Paradigm, Comcast Technology Centre, Philadelphia, USA 2017 Beijing Canopy, Guo Rui Square, Beijing, China 2016 The Optic Cloak, The Energy Centre Greenwich Peninsula, curated by Futurecity, London, UK Paradigm, Francis Crick Institute, curated by Artwise, London, UK 2015 Three Perpetual Chords, Dulwich Park, curated and managed by the Contemporary Art Society for Southwark Council, London, UK 2012 Canopy Study, 123 Victoria Street, London, UK 2010 Fraction (9:8), Sadler Building, Oxford Science Park, curated and managed by Modus Operandi, Oxford, UK 2009 Axiom (Tower), Ministry of Justice, London, UK 2007 Space Trumpet, Unilever House, London, UK Solo Exhibitions 2020 Conrad Shawcross, an extended reality (XR) exhibition on Vortic Collect, Victoria Miro, London, UK Escalations, Château la Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, France Celebrating 800 years of Spirit and Endeavour, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, -

Aftershock: the Ethics of Contemporary Transgressive

HORRORSHOW 5 The Transvaluation of Morality in the Work of Damien Hirst I don’t want to talk about Damien. Tracey Emin1 With these words Tracey Emin deprived the art world of her estimation of her nearest contemporary and perhaps the most notorious artist associated with the young British art phenomenon. Frustrating her interviewer’s attempt to discuss Damien Hirst is of course entirely Emin’s prerogative; why should she be under any obligation to discuss the work of a rival artist in interview? Given the theme of this book, however, no such discursive dispensation can be entertained. Why Damien Hirst? What exactly is problematic about Hirst’s art? It is time to talk about Damien. An early installation When Logics Die (1991) provides a useful starting point for identifying the features of the Hirstean aesthetic. High-definition, post- mortem forensic photographs of a suicide victim, a road accident fatality and a head blown out by a point-blank shotgun discharge are mounted on aluminium above a clinical bench strewn with medical paraphernalia and biohazard material. Speaking to Gordon Burn in 1992, the artist explained that what intrigued him about these images was the incongruity they involve: an obscene content yet amenable to disinterested contemplation in the aesthetic mode as a ‘beautiful’ abstract form. ‘I think that’s what the interest is in. Not in actual corpses. I mean, they’re completely delicious, desirable images of completely undesirable, unacceptable things. They’re like cookery books.’2 Now remember what he’s talking about here. Sustained, speculative and clinically detached, Hirst’s preoccupation with the stigmata of decomposition, disease and mortal suffering may be considered to violate instinctive taboos forbidding pleasurable engagement with the spectacle of death. -

Shirazeh Houshiary B

Shirazeh Houshiary b. 1955, Shiraz, Iran 1976-79 Chelsea School of Art, London 1979-80 Junior Fellow, Cardiff College of Art 1997 Awarded the title Professor at the London Institute Solo Exhibitions 1980 Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff 1982 Kettle's Yard Gallery, Cambridge 1983 Centro d'Arte Contemporanea, Siracusa, Italy Galleria Massimo Minini, Milan Galerie Grita Insam, Vienna 1984 Lisson Gallery, London (exh. cat.) 1986 Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam 1987 Breath, Lisson Gallery, London 1988-89 Centre d'Art Contemporain, Musée Rath, Geneva (exh. cat.), (toured to The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford) 1992 Galleria Valentina Moncada, Rome Isthmus, Lisson Gallery, London 1993 Dancing around my ghost, Camden Arts Centre, London (exh. cat.) 1993-94 Turning Around the Centre, University of Massachusetts at Amherst Fine Art Center (exh. cat.), (toured to York University Art Gallery, Ontario and to University of Florida, the Harn Museum, Gainsville) 1994 The Sense of Unity, Lisson Gallery, London 1995-96 Isthmus, Le Magasin, Centre National d'Art Contemporain, Grenoble (exh. cat.), (touring to Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, Hochschule für angewandte Kunst, Vienna). Organised by the British Council 1997 British Museum, Islamic Gallery 1999 Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, NY 2000 Self-Portraits, Lisson Gallery, London 2002 Musuem SITE, Santa Fe, NM 2003 Shirazeh Houshiary - Recent Works, Lehman Maupin, New York Shirazeh Houshiary Tate Liverpool (from the collection) Lisson Gallery, London 2004 Shirazeh Houshiary, -

John Stezaker

875 North Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL 60611 Tel. 312/642/8877 Fax 312/642/8488 1018 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10075 Tel. 212/472/8787 Fax 212/472/2552 JOHN STEZAKER Born in Worcester, England, 1949. Lives and works in London. EDUCATION 1973 Slade School of Art, London, England SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 The Truth of Masks, Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago, US [cat.] Touch, The Approach at Independent Régence, Brussels, Belgium Film Works, De La Warr Pavilion, East Sussex, UK Collages, Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, the Netherlands The Projectionist, The Approach, London, UK 2014 New Silkscreens, Petzel Gallery, New York, US Collages, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney, Australia 2013 One on One, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, Israel [cat.] Nude and Landscape, Petzel Gallery, New York, US [cat.] Blind, The Approach, London, UK Crossing Over, Galerie Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Germany 2012 John Stezaker, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany Marriage, Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University, Milwaukee, US The Nude and Landscape, University of the Arts, Philadelphia, US [cat.] 2011 John Stezaker, Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK; traveled to Mudam, Luxembourg (2011); Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, St Louis, US (2012) [cat.] John Stezaker, Petzel Gallery, New York, US [cat.] 2010 Silkscreens, Galerie Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Germany [cat.] Lost Images, Kunstverein Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany Tabula Rasa, The Approach, London, UK [cat.] 2009 John Stezaker, Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago, US John Stezaker, Galerie Gisela Capitain, -

Alex Hartley

ALEX HARTLEY BIOGRAPHY 1963 Born in West Byfleet Lives and works in London and Devon EDUCATION 1983-84 Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts (Foundation Course) 1984-87 Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts (BA Hons) 1988-90 Royal College of Art (MA) AWARDS AND COMMISSIONS 2014 b-Side Festival. Artist In residence Portland Dorset 2013 National Trust for Scotland Artist in residence ST. Kilda 2009 Artists Taking the Lead, 2012 Cultural Olympiad commission for the South West 2007 British Embassy, Moscow 2005 Winner of Linklaters Commission, the Barbican, London 2000 Winner of Sculpture at Goodwood ART2000 Commission Prize, London 2004 Shortlisted Banff Mountain book Festival for LA climbs 1999 The Citibank Private Bank Photography Prize, The Photographers’ Gallery SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2011 The World is Still Big, Victoria Miro Gallery, London 2008 Leeds Metropolitan Gallery, Leeds 2007 Edinburgh Art Festival Exhibition, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh 2005 Don’t want to be part of your world, Victoria Miro Gallery, London 2003 Outside, Distrito Cuatro, Madrid 2001 Case Study, Victoria Miro Gallery, London 1998 Lumen Travo, Amsterdam 1998 Galerie Ulrich Fiedler, Cologne 1997 James Van Damme Gallery, Brussels 1997 Viewer, Victoria Miro Gallery, London 1995 Fountainhead, Victoria Miro Gallery, London 1995 Galerie Gilles Peyroulet, Paris 1993 Victoria Miro Gallery, London 1993 James Van Damme Gallery, Antwerp 1992 Anderson O’Day Gallery, London PROJECTS 2012 Artists Taking the Lead, 2012 Cultural Olympiad : Nowhereisland GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2013 ARCTIC, -

You Cannot Be Serious: the Conceptual Innovator As Trickster

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5791 Chapter 8: You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster The Accusation The artist does not say today, “Come and see faultless work,” but “Come and see sincere work.” Edouard Manet, 18671 When Edouard Manet exhibited Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe at the Salon des Refusés in 1863, the critic Louis Etienne described the painting as an “unbecoming rebus,” and denounced it as “a young man’s practical joke, a shameful open sore not worth exhibiting this way.”2 Two years later, when Manet’s Olympia was shown at the Salon, the critic Félix Jahyer wrote that the painting was indecent, and declared that “I cannot take this painter’s intentions seriously.” The critic Ernest Fillonneau claimed this reaction was a common one, for “an epidemic of crazy laughter prevails... in front of the canvases by Manet.” Another critic, Jules Clarétie, described Manet’s two paintings at the Salon as “challenges hurled at the public, mockeries or parodies, how can one tell?”3 In his review of the Salon, the critic Théophile Gautier concluded his condemnation of Manet’s paintings by remarking that “Here there is nothing, we are sorry to say, but the desire to attract attention at any price.”4 The most decisive rejection of these charges against Manet was made in a series of articles published in 1866-67 by the young critic and writer Emile Zola. -

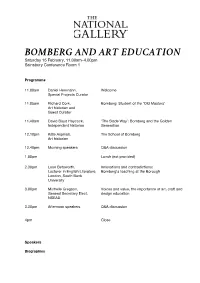

Bomberg Study Day Programme

BOMBERG AND ART EDUCATION Saturday 15 February, 11.00am–4.00pm Sainsbury Conference Room 1 Programme 11.00am Daniel Herrmann, Welcome Special Projects Curator 11.05am Richard Cork, Bomberg: Student of the ‘Old Masters’ Art historian and Guest Curator 11.40am David Boyd Haycock, ‘The Slade Way’: Bomberg and the Golden Independent historian Generation 12.10pm Kate Aspinall, The School of Bomberg Art historian 12.40pm Morning speakers Q&A discussion 1.00pm Lunch (not provided) 2.30pm Leon Betsworth, Innovations and contradictions: Lecturer in English Literature, Bomberg’s teaching at the Borough London, South Bank University 3.00pm Michelle Gregson, Voices and value, the importance of art, craft and General Secretary Elect, design education NSEAD 3.30pm Afternoon speakers Q&A discussion 4pm Close Speakers Biographies Daniel F. Herrmann is Curator of Modern & Contemporary Projects at the National Gallery, where he worked on Young Bomberg and the Old Masters (2019), with Richard Cork, and Bridget Riley: Messengers (2019). He was previously a curator at Whitechapel Gallery. He is writing the catalogue raisonné of Eduardo Paolozzi’s prints. Richard Cork is an award-winning art critic, historian, broadcaster and exhibition curator, as well as an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Academy. He wrote a major monograph on David Bomberg in 1987 and curated the Tate’s first large solo exhibition of Bomberg’s work in 1988. David Boyd Haycock specializes in 20th-century British art. He is author of a number of books including 'Paul Nash' (2016) and 'A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War' (2009). -

Sean Landers Cv 2021 0223

SEAN LANDERS Born 1962, Palmer, MA Lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION 1986 MFA, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT 1984 BFA, Philadelphia College of Art, Philadelphia, PA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, 2020 Vision, April 26–ongoing (online presentation) Greengrassi, London, UK, Northeaster, June 16–July 31 Consortium Museum, Dijon, France, March 13– October 18, curated by Eric Troncy 2019 Ben Brown Fine Arts, Hong Kong, China, November 12–January 9, 2020 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium, November 9–December 20 (catalogue) Petzel Bookstore, New York, NY, Curated by . Featuring Sean Landers, November 7– December 14 Freehouse, London, UK, Sean Landers: Studio Films 90/95, curated by Daren Flook, January 13–February 24 2018 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, March 1–April 21 (catalogue) 2016 Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Germany, Sean Landers: Small Brass Raffle Drum, September 16– October 29 2015 Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan, December 5–January 16, 2016 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium, October 29–December 19 (catalogue) China Art Objects, Los Angeles, CA, February 21–April 11 2014 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, Sean Landers: North American Mammals, November 13– December 20 (catalogue) 2012 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium, November 8–December 21(catalogue) Sorry We’re Closed, Brussels, Belgium, Longmore, November 8–December 21 greengrassi, London, UK, April 26–June 16 1 2011 Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, Sean Landers: Around the World Alone, May 6–June 25 Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY, Sean Landers: A Midnight Modern Conversation, April 21–June 18 (catalogue) 2010 Contemporary Art Museum St. -

Unlike Most Other Artists, Particularly Those Involved in the Performing Arts Home’ in a Way I Never Had Before

Unlike most other artists, particularly those involved in the performing arts home’ in a way I never had before. I discovered that to be an artist was to – dancers, musicians, actors, and film-makers – visual artists rarely work as become part of a community of people engaged through their individual part of an ensemble or where individuals combine their different skills and work in a passionate and on-going debate about art. Amongst my fellow roles to produce a single common work. students were Richard Serra, Chuck Close, and Brice Marden. My whole sense of myself as an artist was established at Yale. When I came to Britain Although there are a number of examples today of pairs of artists in 1966 I felt immediately welcome because the community of artists does working as a single creative unit – e.g. Gilbert and George, Fischli and Weiss, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Webster and Noble – and many artists work with assistants, sometimes teams of assistants – the defining characteristic of contemporary art is that of the individual vision defined through an individually developed and recognisable visual language. At a crucial level visual artists work alone. Their work must define and confirm the difference between their vision and that of other artists. Yet, in my experience, of all the arts, none has a more highly developed and pervasive sense of community than the visual arts. Few romantic ideas about art are more misguided than that of the isolated genius. In general the engagement with other artists begins in art school. Ideally an art school creates an intense experience of competitive discourse and common purpose amongst its students as well as between the students and their teachers, and through them, with the wider art world beyond the school, the world of exhibitions, galleries, publications, museums, etc. -

Young British Artists: the Legendary Group

Young British Artists: The Legendary Group Given the current hype surrounding new British art, it is hard to imagine that the audience for contemporary art was relatively small until only two decades ago. Predominantly conservative tastes across the country had led to instances of open hostility towards contemporary art. For example, the public and the media were outraged in 1976 when they learned that the Tate Gallery had acquired Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (the bricks) . Lagging behind the international contemporary art scene, Britain was described as ‘a cultural backwater’ by art critic Sarah Kent. 1 A number of significant British artists, such as Tony Cragg, and Gilbert and George, had to build their reputation abroad before being taken seriously at home. Tomake matters worse, the 1980s saw severe cutbacks in public funding for the arts and for individual artists. Furthermore, the art market was hit by the economic recession in 1989. For the thousands of art school students completing their degrees around that time, career prospects did not look promising. Yet ironically, it was the worrying economic situation, and the relative indifference to contemporary art practice in Britain, that were to prove ideal conditions for the emergence of ‘Young British Art’. Emergence of YBAs In 1988, in the lead-up to the recession, a number of fine art students from Goldsmiths College, London, decided it was time to be proactive instead of waiting for the dealers to call. Seizing the initiative, these aspiring young artists started to curate their own shows, in vacant offices and industrial buildings. The most famous of these was Freeze ; and those who took part would, in retrospect, be recognised as the first group of Young British Artists, or YBAs. -

British Society and the 'Tate War'

British Society and the ‘Tate War’ Antony Lerman I feel very privileged to have been invited to what so far has been a truly fascinating, informative, moving and thought-provoking symposium. As someone who is not an art historian and who knew very little about Kitaj before Cilly Kugelmann very kindly, and very bravely I feel, invited me to speak, what I have heard and seen so far has been a unique and rewarding learning experience. I’m here because my expertise is in the field of contemporary antisemitism and Cilly thought that I might be able to look at the ‘Tate War’ and the argument that antisemitism was a key factor behind the critics’ attacks on the 1994 Retrospective from a fresh, or at least different, perspective. And I want to thank her and all the organisers and sponsors for giving me this opportunity to offer my thoughts on this vexed issue. I should make it clear that I have reached some conclusions, which I think you’ll find somewhat different from some of what was said on this very topic yesterday. But, Ladies and Gentlemen, I make no claims to have settled the matter definitively and I respect the views of others here. By the very nature of antisemitism, there are many instances in which it’s ultimately impossible to prove one way or the other whether actions taken or things said were motivated by it. As I found, the deeper you look into this case, the more variables you discover that have a bearing on any judgment you might make.