Spencer Baird and the Foundations of American Marine Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spencer Fullerton Baird

PROFESSOR SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Spencer Fullerton Baird HDT WHAT? INDEX SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD 1784 December 27: Elihu Spencer died (Spencer Fullerton Baird would be a great-grandson). HDT WHAT? INDEX SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD 1823 February 3, Monday: Spencer Fullerton Baird was born. Gioachino Rossini’s melodramma tragico Semiramide to words of Rossi after Voltaire was performed for the initial time, in Teatro La Fenice, Venice, with a very enthusiastic response (this was the last opera Rossini would write for Italy). NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT Spencer Fullerton Baird “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD 1829 June 27, Saturday: James Smithson, who had been born in Paris in 1765, died of natural causes in Genoa. When Smithson had made his will, he had been miffed at the snottiness of British nobles to whom he was related by blood: “My name shall live in the memory of man when the titles of the Northumberlands and the Percys are extinct and forgotten.”1 A minor stipulation in the will, in which he tried to leave everything to friendlier relatives, was that should his beneficiary die without issue, he wanted the estate to be used to create a “Smithsonian Institution” dedicated to “the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men,” and stipulating also that this institution should be set up in the USA, a country toward which he had never displayed the slightest interest. -

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

The Bluefish, an Unsolved History: Spencer Fullerton Baird's Window Into Southern New England's Coastal Fisheries

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2018 The Bluefish, An Unsolved History: Spencer Fullerton Baird's Window into Southern New England's Coastal Fisheries Elenore Saunders Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Weatherly Saunders Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Recommended Citation Saunders, Elenore and Saunders, Weatherly, "The Bluefish, An Unsolved History: Spencer Fullerton Baird's Window into Southern New England's Coastal Fisheries". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2018. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/687 The Bluefish, An Unsolved History: Spencer Fullerton Baird’s Window into Southern New England’s Coastal Fisheries Weatherly Saunders Trinity College History Senior Thesis Advisor: Thomas Wickman Spring, 2018 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................4 One: The Diseased Bluefish? The Nantucket epidemic of 1763-1764 and the disappearance of the local bluefish....................20 Two: The Bloodthirsty Bluefish Baird’s unique outlook on the coastal fishery decline due to combined human and natural -

Robert Ridgway 1850-1929

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XV SECOND MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF ROBERT RIDGWAY 1850-1929 BY ALEXANDER WETMORE PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1931 ROBERT RIDGWAY 1850-1929 BY ALEXANDER WETMORE Robert Ridgway, member of the National Academy of Science, for many years Curator of Birds in the United States National Museum, was born at Mount Carmel, Illinois, on July 2, 1850. His death came on March 25, 1929, at his home in Olney, Illinois.1 The ancestry of Robert Ridgway traces back to Richard Ridg- way of Wallingford, Berkshire, England, who with his family came to America in January, 1679, as a member of William Penn's Colony, to locate at Burlington, New Jersey. In a short time he removed to Crewcorne, Falls Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in farming and cattle raising. David Ridgway, father of Robert, was born March 11, 1819, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. During his infancy his family re- moved for a time to Mansfield, Ohio, later, about 1840, settling near Mount Carmel, Illinois, then considered the rising city of the west through its prominence as a shipping center on the Wabash River. Little is known of the maternal ancestry of Robert Ridgway except that his mother's family emigrated from New Jersey to Mansfield, Ohio, where Robert's mother, Henrietta James Reed, was born in 1833, and then removed in 1838 to Calhoun Praifle, Wabash County, Illinois. Here David Ridgway was married on August 30, 1849. Robert Ridgway was the eldest of ten children. -

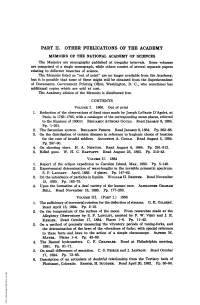

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2. -

The Migrant 47:2

JmuE, 1976 VOL. 47, NO*2 THE MIGRANT A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNXTHOL , 3- . FIRST PUBLISTXED, JUNE 1930 ', ,' ,.. i ,<, . -<* - .* >, '.+ - , , . , - *. .'>> >. *- -.I- , _=_,. PUBUHED BY SEE ORNITHOLOGICAL SEE EDITOR .........................................................................GARY 0.WUCE RL 7, hx338, Su THE SEASON" EDITOR .... FRED J. ALSOP, m Rt. 6, 302 Ever "STATE COUNT COMPILER- .............................. MOI~RISD. VICE-PRESIDENT, EAST TENN. ...................................... BILL WILUAMS 13 13 Young Ave, Maryvillc, Tena 37801 CE-PRISIDENT, MIDDLE TENN. ............................ PAUL CRAWFORD Route 4, Gallatin, Tenn. 37066 E-PRESIDENT, WEST TENN. ........................ nIANDARLINGTON 3112 GIentinnan'Rd, Memphis, Tenn. 38128 IRECTORS-AT-URGE: EAST TENM. .......................................................................... JON IhVORE 4922 Sarlsota Dr.. Hixson.- * Tcnn....... 37343 MIDDLE TEW. ................................ .. ...................... DAVID HASSLER ,,, , , Box 1, Byrdstown, Tcnn. 38549 WEST ............................................... MRS. C. K. J. 101 St, 38079 1 Churcb - TipmvilIe,- Tenn. CURATOR ........................................................................JAMES T. TANNER Rr. 28, Box 155, Knoxville, Tcnn. 37920 SECRETARY ........................................................... MISS LOUISE JACKSON 5037 Montclair Dr., Nashville, Tam. 3721I TREASWRIR ........................................................... KENNETH H. Dm Rt. I, Box 134-I), OoItewah, Tenn. 37363 Anad dnw -

The Systematics of Crotaphytus Wislizeni, the Leopard Lizards, Part I

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 23 Article 2 Number 3 – Number 4 12-16-1963 The systematics of Crotaphytus wislizeni, the leopard lizards, Part I. A redescription of Crotaphytus wislizeni wislizeni Baird and Girard, and a description of a new subspecies from the Upper Colorado River Basin Wilmer W. Tanner Brigham Young University Benjamin H. Banta Colorado College, Colorado Springs Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Tanner, Wilmer W. and Banta, Benjamin H. (1963) "The systematics of Crotaphytus wislizeni, the leopard lizards, Part I. A redescription of Crotaphytus wislizeni wislizeni Baird and Girard, and a description of a new subspecies from the Upper Colorado River Basin," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 23 : No. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol23/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE SYSTEMATICS OF CROTAPHYTUS WISLIZENI, THE LEOPARD LIZARDS PART I A REDESCRIPl ION OF CROTAPHYTUS WISLIZENI WISLIZENI Baird and Girard, AND A DESCRIPIION OF A NEW SUBSPECIES FROM THE UPPER COLORADO RIVER BASIN^ Wilmer W. Tanner and Benjamin H. Banta* One group of North American iguanid lizards to receive slight consideration for systematic studies has been the leopard lizard, Crotaphytus wislizeni. This species has a wide distribution occur- ring in most of the arid and semi-arid basins of western North America, i.e. -

'Ibaieucanj/Fllsdum

'IoxfitatesibAieucanJ/fllsdum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y. I0024 NUMBER 2350 OCTOBER 4, I968 Zoological Exploration in Mexico the Route of Lieut. D. N. Couch in 1853 BY ROGER CONANT1 Lieutenant Darius Nash Couch was an enthusiastic and productive naturalist who spent several months in Mexico during 1853, traveling under the aegis of the Smithsonian Institution. He assembled a con- siderable collection of vertebrates, many of which eventually became the types of new species, some named for him. Kellogg (1932, pp. 6, 52), in his review of persons who collected am- phibians for the United States National Museum, included a number of facts about Couch but stated that a report on Couch's expedition, although written, had never been published. Dr. Alexander Wetmore advised me (personal communication), while he was Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, that neither field notes nor any detailed report by Couch had ever been found. Precise information on Couch's itinerary therefore is lacking, and persons who study his material are often con- fronted with the problem of trying to determine exactly where he worked in the field. A case in point was my own effort to pinpoint the type localities of several natricine snakes ascribed to him as collector. So many data were assembled in the process, however, that I was encour- aged to reconstruct Couch's route in considerable detail. Publication of this information was originally intended for inclusion in a monographic study of the genus Natrix in Mexico, but Couch's travels probably will 1 Research Associate, Department of Herpetology, the American Museum of Natural History; Director and Curator of Reptiles, Philadelphia Zoological Garden. -

Publicity Records, 1955-1979

Publicity Records, 1955-1979 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Publicity Records https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_252245 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Publicity Records Identifier: Accession 95-043 Date: 1955-1979 Extent: 1 cu. ft. (1 record storage box) Creator:: Smithsonian Institution. Office of Public Affairs Language: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 95-043, Smithsonian Institution, Office of Public Affairs, Publicity Records Descriptive Entry This accession consists of back issues of the Torch, press clippings from the 1960s and 1970s along with subject files concerning the Secretaries, publicized deaths of Smithsonian Institution staff -

Cloudsley Louis Rutter (1867–1903): Pioneer Salmon Biologist and Resident Naturalist, Fisheries Steamer Albatross

Cloudsley Louis Rutter (1867–1903): Pioneer Salmon Biologist and Resident Naturalist, Fisheries Steamer Albatross MARK R. JENNINGS “...accomplish your work even if it is a little hard on others; as their assistance in a suc- cessful work will refl ect credit on them as well as yourself.” Cloudsley Rutter (1903)1 Introduction tion from American universities. This and other important fi sheries resources By the beginning of the 20th centu- was the result of nearly 3 decades of along the Pacifi c coast (Smith, 1910; ry, the United States Fish Commission effort by a relatively small group of Larkin, 1970). A number of dedicated (USFC) had reached a milestone long educators and government offi cials professionals both inside and outside envisioned by its fi rst Commissioner (Brittan, 1997). the USFC felt that they could restore Spencer Fullerton Baird: an agency This period was also the height of declining and depleted salmon runs largely staffed with scientists well- the Progressive Era, a time where by taking a scientifi c approach to the trained in the fi eld of fi sheries biology great faith was placed in the notion problem, mainly by studying the life and assisted, as needed, by a cadre of that scientifi c investigation could history and ecology of each species university professionals (Allard, 1978; solve many political, social, and eco- in the fi eld, suggesting regulations to Jennings, 1997a). From senior direc- nomic problems, including the rapid limit commercial fi shing (or identify tors down to intermittent fi eld assis- destruction of the nation’s natural re- new fi shing grounds), and building tants, a majority of USFC employees sources (Hays, 1959). -

Installation of the Twelfth Secretary Smithsonian Institution

H S O N T I I A M N S I N N S T O I T U T I Installation of the Twelfth Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian Monday, January 26, 2009 Installation Ceremony Program Presiding The Honorable John G. Roberts, Jr. Chief Justice of the United States Chancellor, Smithsonian Institution Musical Prelude The Smithsonian Chamber Players Presentation of the Colors Joint Armed Forces Color Guard, Military District of Washington National Anthem Mr. Manuel Melendez International Liaison, Smithsonian Institution Welcome Remarks Mr. Roger W. Sant Chair, Smithsonian Institution Board of Regents Presentation of the Smithsonian Mace Smithsonian Honor Guard Academic Procession Welcomes and Felicitations Native American Honoring Welcome Mr. Clayton Old Elk (Crow) On behalf of the Smithsonian Volunteers Ms. Donna DeCorleto Volunteer Information Specialist and Behind-the-Scenes Volunteer On behalf of the Smithsonian Scholars Dr. Franklin Odo Director, Asian Pacific American Program On behalf of the Smithsonian Staff Officer Darryl King Museum Protection Officer, National Air and Space Museum On behalf of the Scholarly Community Dr. Charles M. Vest President, National Academy of Engineering On behalf of the Board of Regents Ms. Patricia Q. Stonesifer Chair-elect and Vice Chair, Smithsonian Institution Board of Regents The Honorable Thad Cochran Member, United States Senate Regent, Smithsonian Institution Installation The Honorable John G. Roberts, Jr. Chief Justice of the United States Chancellor, Smithsonian Institution Remarks Dr. G. Wayne Clough Twelfth Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution Closing Remarks Mr. Roger W. Sant Chair, Smithsonian Institution Board of Regents The Smithsonian Chamber Players Kenneth Slowik Artistic Director Marilyn McDonald and Marc Destrubé violins Kenneth Slowik violoncello Colin St. -

THE "BAIRD MEMORIAL" Ciety Places This Tablet in Appreciation of His Inestimable Services to Ichthyol Ogy, Pisciculture and the Fisheries

The 'Baird Memorial" Item Type article Download date 04/10/2021 02:40:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/26461 THE "BAIRD MEMORIAL" ciety places this tablet in appreciation of his inestimable services to Ichthyol ogy, Pisciculture and the Fisheries. 1902." President Bowers-It gives me plea sure to present to you Mr. E. W. Blatchford, who has been selected to deliver one of the addresses on this oc casion. Address of E. W. Blatchford Mr. President and members of the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries and of the American Fisheries Society, faculty and students of the Ma rine Biological School, ladies and gentlemen: It is three years since I had the honor of urging upon the American Fisheries Society, in response to resolu tions presented by Dr. Smith, the erec tion of a monument to the memory of In mid 1903, during the annual meet "At a former meeting of the Ameri Professor Baird, and the appropriateness ing of the American Fisheries Society, can Fisheries Society a resolution was that such memorial should be located AFS members, U.S. Fish Commission passed suggesting the erection of a tab here, the scene of much of his most suc (USFC) staff, and other interested per let to the memory of Prof. Spencer F. cessful and distinguished scientific la sons gathered at Woods Hole, Mass., to Baird, an appropriate tribute and recog bor. The proposition met with an en dedicate a permanent memorial to Spen nition of the distinguished labors in be thusiastic response, both from your so cer F.