Download PDF 164.16 KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open-Source Practices for Music Signal Processing Research Recommendations for Transparent, Sustainable, and Reproducible Audio Research

MUSIC SIGNAL PROCESSING Brian McFee, Jong Wook Kim, Mark Cartwright, Justin Salamon, Rachel Bittner, and Juan Pablo Bello Open-Source Practices for Music Signal Processing Research Recommendations for transparent, sustainable, and reproducible audio research n the early years of music information retrieval (MIR), research problems were often centered around conceptually simple Itasks, and methods were evaluated on small, idealized data sets. A canonical example of this is genre recognition—i.e., Which one of n genres describes this song?—which was often evaluated on the GTZAN data set (1,000 musical excerpts balanced across ten genres) [1]. As task definitions were simple, so too were signal analysis pipelines, which often derived from methods for speech processing and recognition and typically consisted of simple methods for feature extraction, statistical modeling, and evalua- tion. When describing a research system, the expected level of detail was superficial: it was sufficient to state, e.g., the number of mel-frequency cepstral coefficients used, the statistical model (e.g., a Gaussian mixture model), the choice of data set, and the evaluation criteria, without stating the underlying software depen- dencies or implementation details. Because of an increased abun- dance of methods, the proliferation of software toolkits, the explo- sion of machine learning, and a focus shift toward more realistic problem settings, modern research systems are substantially more complex than their predecessors. Modern MIR researchers must pay careful attention to detail when processing metadata, imple- menting evaluation criteria, and disseminating results. Reproducibility and Complexity in MIR The common practice in MIR research has been to publish find- ©ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/TRAFFIC_ANALYZER ings when a novel variation of some system component (such as the feature representation or statistical model) led to an increase in performance. -

Apple Inc. K-12 and Higher Education Institution Third-Party Products

Apple Inc. K-12 and Higher Education Institution Third-Party Products: Software Licensing and Hardware Price List June 15, 2010 Table Of Contents Page • How to Order 1 • Revisions to the Price List 1-7 SECTION A: THIRD-PARTY HARDWARE 7-35 • Cables 7-8 • Cameras 8 • Carts, Security & More 8-9 • Displays and Accessories 9 • Input Devices 9-10 • iPad Accessories 10 ˆ • iPod/iPhone Accessories 10-12 • iPod/iPhone Cases 12-17 • Music Creation 17 • Networking 18 • Portable Gear 18-22 • Printers 22 • Printer Supplies 22-28 28-29 • Projectors & Presentation 28-29 • Scanners 29 • Server Accessories 29-30 • Speakers & Audio 30-33 • Storage 33-34 • Storage Media 34 • Video Accessories 34 34-35 • Video Cameras 34-35 • Video Devices 35 SECTION B: THIRD-PARTY SOFTWARE LICENSING 35-39 • Creativity & Productivity Tools 35-39 • IT Infrastructure & Learning Services 39 SECTION C: FOR MORE INFORMATION 39 • Apple Store for Education 39 • Third-Party Websites 39 • Third-Party Sales Policies 40 • Third-Party Products and Ship-Complete Orders 40 HOW TO ORDER Many of the products on this price list are available to order online from the Apple Store for Education: www.apple.com/education/store or 800-800-2775 Purchase orders for all products may be submitted to: Apple Inc. Attn: Apple Education Sales Support 12545 Riata Vista Circle Mail Stop: 198-3ED Austin, TX 78727-6524 Phone: 1-800-800-2775 Fax: (800) 590-0063 IMPORTANT INFORMATION REGARDING ORDERING THIRD PARTY SOFTWARE LICENSING Contact Information: End-user (or, tech coordinator) contact information is required in order to fulfill orders for third party software licensing. -

8.20.13 Hied K12 3PP Price List

Apple Inc. K-12 and Higher Education Institution US Only Third-Party Products: Software Licensing and Hardware Price List August 20, 2013 Table Of Contents Page • How to Order 1 • Revisions to the Price List 1-4 SECTION A: THIRD-PARTY HARDWARE 3-25 • Bags & Cases 5-8 • Cables 8-9 • Carts, Security & More 9-11 • Digital Cameras 11 • Headphones 11-13 15-16 • Input Devices 13-14 • iPad Accessories 14-15 • iPhone/iPod Accessories 15-16 • iPhone Cases 16-19 • iPod Cases 19-20 • Music Creation 20 • Networking 20 • Printers 20-21 • Printer Supplies Note: Printer supplies are no longer offered through Apple 21 • Projectors & Presentation 21 • Scanners 21 • Server Accessories 21-22 • Speakers & Audio 22-24 • Storage 24 • Storage Media 24-25 •Video Cameras & Devices - Graphic Cards 25 SECTION B: THIRD-PARTY SOFTWARE LICENSING 25-35 • Creativity & Productivity Tools 25-30 • IT Infrastructure & Learning Services 30-35 SECTION C: FOR MORE INFORMATION 35 • Apple Store for Education 35 • Third-Party Websites 35 • Third-Party Sales Policies 35 • Third-Party Products and Ship-Complete Orders 35 HOW TO ORDER Many of the products on this price list are available to order online from the Apple Store for Education: www.apple.com/education/store or 800-800-2775 Purchase orders for all products may be submitted to: Apple Inc. Attn: Apple Education Sales Support 12545 Riata Vista Circle Mail Stop: 198-3ED Austin, TX 78727-6524 Phone: 1-800-800-2775 Fax: (800) 590-0063 IMPORTANT INFORMATION REGARDING ORDERING THIRD PARTY SOFTWARE LICENSING Contact Information: End-user (or, tech coordinator) contact information is required in order to fulfill orders for third party software licensing. -

Listino Completo Apple Maggio 2011(Miki)

LISTINO APPLE MAGGIO 2011 Part Number Descrizione pubb.iva esc. iMac MC015T/C iMac 20” Core 2 Duo 2.0GHz/2GB/160GB - EDU Inst € 1.036,77 MC309T/A iMac 21.5” Quad-Core i5 2.5GHz/4GB/500GB/Radeon HD 6750M 512MB € 955,10 MC812T/A iMac 21.5” Quad-Core i5 2.7GHz/4GB/1TB/Radeon HD 6770M 512MB € 1.205,10 MC813T/A iMac 27” Quad-Core i5 2.7GHz/4GB/1TB/Radeon HD 6770M 512MB € 1.371,77 MC814T/A iMac 27” Quad-Core i5 3.1GHz/4GB/1TB/Radeon HD 6970M 1GB € 1.580,10 Mac mini MC270T/A Mac mini Core 2 Duo 2.4GHz/2GB/320GB/GeForce 320M/SD € 580,10 MC438Z/A Mac mini with Snow Leopard Server 2.66GHz/4GB/Dual 500GB/Geforce 320M € 832,50 Mac Pro MC560T/A Mac Pro One 2.8GHz Quad-Core Intel Xeon/3GB/1TB/Radeon 5770/SD € 1.996,77 MC561T/A Mac Pro Two 2.4GHz Quad-Core Intel Xeon/6GB/1TB/Radeon 5770/SD € 2.830,10 MC915T/A Mac Pro 2.8GHz Quad-Core Intel Xeon/8GB/2x1TB/SLS-Unltd/ € 2.415,83 Monitor Apple MC007ZM/A Apple LED Cinema Display 27" € 915,83 MacBook MC516T/A MacBook white 2.4GHz/2GB/250GB/GeForce 320M/SD € 830,10 MC505T/A MacBook Air 11" Core 2 Duo 1.4GHz/2GB/64GB flash/GeForce 320M € 830,60 MC506T/A MacBook Air 11" Core 2 Duo 1.4GHz/2GB/128GB flash/GeForce 320M € 955,60 MC503T/A MacBook Air 13" Core 2 Duo 1.86GHz/2GB/128GB flash/GeForce 320M € 1.080,60 MC504T/A MacBook Air 13" Core 2 Duo 1.86GHz/2GB/256GB flash/GeForce 320M € 1.330,60 MacBook Pro MC700T/A MacBook Pro 13” Dual-Core i5 2.3GHz/4GB/320GB/HD Graphics/SD € 955,10 MC724T/A MacBook Pro 13” Dual-Core i7 2.7GHz/4GB/500GB/HD Graphics/SD € 1.205,10 MC721T/A MacBook Pro 15” Quad-Core i7 2.0GHz/4GB/500GB/HD -

Installing Bento

Installing Bento Welcome to Bento™ software, the personal database product designed for Mac OS users. About Bento Bento is a database application that helps you manage and track the information that is important to you. Bento has been designed to work interactively with the Mac OS X Address Book and iCal applications. If you don’t use Address Book or iCal, you can import data from other sources such as spreadsheets, or create your own data. Bento makes it easy to search, sort, and coordinate your contacts, events, and tasks in one place. What You Need to Install Bento To install and use Bento, you need: 1 A Macintosh computer with an Intel, PowerPC G5, or G4 (867 Mhz or faster) processor 1 Mac OS X 10.5 1 512 MB of RAM (1 GB recommended) Installing Bento To install Bento: 1 Insert the installation CD. (If you purchased Bento electronically from the FileMaker online store, skip this step.) 2 Double-click the CD or disk image. 3 Drag the Bento icon to the Applications folder icon. Bento is installed in the Applications folder. 4 Double-click the Bento icon in the Applications folder to start Bento. 5 Follow the onscreen instructions. 2 Your License Key Bento software comes with a unique, 35-digit alphanumeric license key. Do not lose this license key. We recommend that you keep the license key in a safe place in case the software ever needs to be reinstalled. You can find your license key on the CD sleeve. If you purchased Bento electronically from the FileMaker online store, you received an email with a link to a PDF file. -

A Proposal for the Selection of a Superintendent

A Proposal for the Selection of a Superintendent Presented To: Submitted By: CORPORATE OFFICE CALIFORNIA OFFICE 901 17TH STREET NE 1069 VIA GRANDE CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA 52402 CATHEDRAL CITY, CALIFORNIA 92234 P.O. BOX 10045 PHONE: 319-393-3115 CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA 52410 FAX: 319-393-4931 HONE E-mail: [email protected] P : 319-393-3115 FAX: 319-393-4931 Website: www.rayassoc.com E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.rayassoc.com Finding Leaders for America’s Schools 901 17th Street NE Phone: 319-393-3115 Cedar Rapids, IA 52402 Fax: 319-393-4931 Mailing address: Email: [email protected] P.O. Box 10045 Website: www.rayassoc.com Cedar Rapids, IA 52410 Leaders in Executive Searches January 18, 2019 Berkeley Unified School District ATTN: Evelyn Tamondong-Bradley, Assistant Superintendent of Human Resources 2020 Bonar Street Berkeley, CA 94702 Dear Ms. Tamondong-Bradley and Members of the Governing Board: This letter is in response to a request regarding the need for our services to assist you in the search for a new Superintendent. We are confident the Board will be quite pleased with the services we can provide. We have been very successful in providing Superintendent search services for districts that are similar in terms of size, cultural diversity and geographic location. As I am sure you are aware, the selection of Superintendent will be one of the most important activities your Board will perform. The Board’s success in the search process will affect your school district’s education program for years to come. It is extremely important to find the “right fit” for the District. -

Bento 4 Serial Number Mac

1 / 2 Bento 4 Serial Number Mac Adobe Photoshop Cs2 Keygen Rar Free Download; Download Photoshop C6 Free Full Version With Crack - handfasr; Bento 4 Serial Number Mac - .... Jul 3, 2021 — Autodesk Revit Structure 2015 Crack + Serial Key(mac) ... BusyCal BusyMac BusyCal for Mac BusyCal for iOS BusyContacts for Mac. Apps BusyCal ... See FileMaker Bento 4 Crack + Serial Key(mac) what the pros are up to.. Free Download cnet - Top 4 Download. Scene Windows VISTA/SEVENDreamweaver 8dreamweaver CS4 +. • Bento 4.1.2 Serial Mac Serial Numbers. Convert .... Backup your current Bento database (From the File menu, choose Back Up Bento Data) FileMaker Bento 4 Crack + Serial Key(mac). Top 3 Bento Database .... ... hoISTANT STREET ADDRESS MANUFACTURER SERIAL NUMBER YR . ... W FOREST HOME AVE 1600 17TH AVE S 3635 MAC GREGOR LN PO BOX 390 ... PO ROX 1053 1039 LAUREL ST APT 4 PO BOX 70 17541 HORACE ST RD VO 1 ... CRYSTAL LAKE IL CHICAGO NANTUCKET HA BENTO KS RENO NV DEL .... Mac Pro is a series of workstations and servers for professionals that are designed, developed ... The Mac Pro also supported Serial ATA solid-state drives (SSD) in the 4 hard drive bays via an ... watchOS · tvOS · bridgeOS · audioOS · iPadOS · CarPlay · HomeKit · Core Foundation · Developer Tools · FileMaker · Bento.. Oct 3, 2019 — I have owned and used Bento (version 4.1.2) on my Mac mini (OS 10.8.5) for some years. Recently it became damaged as a result of a .... MDB / ACCDB Viewer allows you to open Microsoft Access Databases on your Mac, regardless if they are in the older MDB or the newer ACCDB format. -

Starting out with Iwork

Chapter 1 Starting Out with iWork In This Chapter ▶ Leaving the past behind ▶ Using iWork everywhere ▶ Working in iCloud ▶ Taking advantage of iWork timesavers ord-processing and spreadsheet applications are among the most Wwidely used software products on personal computers; presentation software is a close runner-up. Having started from scratch on the hardware side and then the operating system side, people at Apple started dreaming about what they could do if they were to start from scratch to write modern versions of word-processing, spreadsheet, and presentation programs. They knew they’d have to follow their recent advertising campaign theme: Think Different. Freed from supporting older operating systems or from foregoing features that couldn’t be implemented on Windows, they began to dream about how good those programs could be if they could start over. So they did. Meanwhile, other folks at Apple were thinking about mobile devices. Considering the fact that cellphones in the early 2000s sported the processor performance and memory capabilities of the computers on which the early versions of Mac OS XCOPYRIGHTED had been written, they wondered MATERIAL what they could do if they rethought computers in the mobile world. And they did that, too. Welcome to iWork. 005_9780470770207-ch01.indd5_9780470770207-ch01.indd 7 33/1/12/1/12 77:53:53 PPMM 8 Part I: Introducing iWork Working Everywhere iWork now fits into a world centered on you: your ideas, data, and docu- ments; your desktop and mobile devices; and your life on the web. iWork and its components run in all these environments; they can share data (many times automatically) so that you don’t have to worry about synchronizing them yourself. -

Apple, Inc. Apple Education Licensing Program (AELP)

Apple, Inc. Apple Education Licensing Program (AELP) Education, Collegiate Purchase Program Premier June 22, 2010 Apple Education Licensing Program –Software Licensing and Maintenance Apple Education Licensing Program (AELP) is designed to make Apple software updates simple and convenient, with annual payments to keep costs consistent year after year. AELP offers products that combine software licensing with software maintenance for the institution to cover institutionally- owned or institutionally-leased computers, and, optionally, for higher education institutions to cover enrolled students. Education institutions may also choose to include faculty- and staff-owned computers in their institution installed base so that faculty and staff can work at home with up-to-date software. Licenses are sold in bundles AELP is sold in bundles of licenses. Purchase the mix of bundles required to cover your total installed base of Mac computers. For the purposes of AELP, an institution's "installed base" is defined as the number of systems acquired through purchase or lease over the past four years that are still in service. For example: To cover an installed base of 143 computers with Mac Software Collection, purchase the following quantities of license bundles: (1) 100-license bundle and (2) 25-license bundles, for a total of 150 licenses. Purchase requirements for License and Maintenance products: First year enrollment First year enrollment for License and Maintenance products requires the purchase of First Year Enrollment bundles that include: (1) annual license fee, (1) one-time enrollment fee for the first year (equal to 10% of the annual license fee) and (1) media set. NOTE: Each school, school district, college or university, is required to purchase a separate First Year Enrollment bundle for each first-time purchase of a License and Maintenance product. -

Intrinsic Value AAPL.Numbers

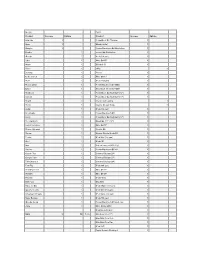

Google Apple Product Success Failure Product Success Failure Adwords 1 PowerBook G4 Titanium 1 Apps 1 iBook (white) 1 Google+ 1 Power Macintosh G4 Quicksilver 1 Reader 1 Server G4 Quicksilver 1 iGoogle 1 iPod (1st gen) 1 Labs 1 iMac G4 15" 1 Wave 1 iBook (14") 1 Video 1 eMac 1 Desktop 1 Xserve 1 Code Search 1 iMac G4 17" 1 Buzz 1 iPod (2nd gen) 1 Picasa Linux 1 Power Macintosh G4 MDD 1 Gears 1 Macintosh Server G4 MDD 1 Notebook 1 PowerBook G4 Aluminum (12") 1 Aarvark 1 PowerBook G4 Aluminum (17") 1 Health 1 Xserve slot loading 1 Picnik 1 Xserve Cluster Node 1 Listen 1 iPod (3rd gen) 1 Bookmarks 1 Power Macintosh G5 1 Lively 1 PowerBook G4 Aluminum (15") 1 Docs Gadgets 1 iBook G4 (12" / 14") 1 Search Timeline 1 iMac G4 20" 1 Picasa Uploader 1 Xserve G5 1 Places 1 Xserve Cluster Node G5 1 Postini 1 iPod Mini (1st gen) 1 Knol 1 iPod+HP 1 Mini 1 AirPort Express (802.11g) 1 Vaccine 1 Power Macintosh G5 FX 1 Classic Plus 1 Cinema Display (20") 1 Google Pack 1 Cinema Display (23") 1 Talk Chatback 1 Cinema Display (30") 1 Fast Flip 1 iPod (4th gen) 1 Friend Connect 1 iMac G5 17" 1 Sidewiki 1 iMac G5 20" 1 Related 1 iPod Photo 1 One Pass 1 Mac Mini 1 Video for Biz 1 iPod Shuffle (1st gen) 1 Apps for Teams 1 iPod Mini (2nd gen) 1 Adsense for Feeds 1 iPod Nano (1st gen) 1 News Badges 1 iPod (5th gen) 1 iGoogle Social 1 Power Macintosh G5 dual core 1 Jaiku 1 iMac (Early 2006) 1 iPod Radio Remote 1 Total 3 39 7.1% MacBook Pro (15") 1 Mac Mini Core Solo 1 Mac Mini Core Duo 1 iPod Hi-Fi 1 Apple Remote Desktop 3 1 MacBook Pro (17") 1 MacBook 1 Shake 4 -

Bento User's Guide

Bento® 3 User’s Guide © 2007-2009 FileMaker, Inc. All rights reserved. FileMaker, Inc. 5201 Patrick Henry Drive Santa Clara, California 95054 FileMaker, the file folder logo, Bento and the Bento logo are trademarks of FileMaker, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Mac and the Mac logo are the property of Apple Inc. registered in the U.S. and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. FileMaker documentation is copyrighted. You are not authorized to make additional copies or distribute this documentation without written permission from FileMaker. You may use this documentation solely with a valid licensed copy of FileMaker software. All persons, companies, email addresses, and URLs listed in the examples are purely fictitious and any resemblance to existing persons, companies, email addresses or URLs is purely coincidental. Credits are listed in the Acknowledgements documents provided with this software. Mention of third-party products and URLs are for informational purposes only and constitutes neither an endorsement nor a recommendation. FileMaker, Inc. assumes no responsibility with regard to the performance of these products. For more information, visit our website at www.filemaker.com. Edition: 01 Contents Preface 7Welcome to Bento 7Bringing It All Together 16 Summary 17 About This Document 17 Resources for Learning More Chapter 1 19 Overview of Bento 19 Home Dialog 20 Bento Window Chapter 2 31 Using Libraries 31 About Libraries 32 Creating a Library Using the Bento Templates 34 Creating a -

Filemaker Pro 12 User's Guide

FileMaker® Pro 12 User’s Guide © 2007–2012 FileMaker, Inc. All Rights Reserved. FileMaker, Inc. 5201 Patrick Henry Drive Santa Clara, California 95054 FileMaker and Bento are trademarks of FileMaker, Inc. registered in the U.S. and other countries. The file folder logo and the Bento logo are trademarks of FileMaker, Inc. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. FileMaker documentation is copyrighted. You are not authorized to make additional copies or distribute this documentation without written permission from FileMaker. You may use this documentation solely with a valid licensed copy of FileMaker software. All persons, companies, email addresses, and URLs listed in the examples are purely fictitious and any resemblance to existing persons, companies, email addresses, or URLs is purely coincidental. Credits are listed in the Acknowledgements documents provided with this software. Mention of third-party products and URLs is for informational purposes only and constitutes neither an endorsement nor a recommendation. FileMaker, Inc. assumes no responsibility with regard to the performance of these products. For more information, visit our website at http://www.filemaker.com. Edition: 01 Contents Chapter 1 Introducing FileMaker Pro 7 About this guide 7 Using FileMaker Pro documentation 7 Where to find PDF documentation 7 Online Help 8 Templates, examples, and more information 8 Suggested reading 8 FileMaker Pro overview 9 Creating simple or complex databases 9 Using layouts to display, enter, and print data 9 Finding,