Atlantic Shore Line Locomotive 100 Curatorial Report No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CANADIAN NATIONAL EDITOR Robert D

iewsletter Ipper Canada Railway Society January 1973 • 90c CANADIAN NATIONAL EDITOR Robert D. IIcMann CONTRIBUTING EDITORS -- Oiarles 0. Begg John D. Thompson Michael W. Roschlau NEWSLETTER is published monthly by the Upper Canada Railway Soci Inc., Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto, Ontario M5W 1A2. Contributions to the NEWSLETTER are solicited. No responsibil can be assumed for loss or non-return of material, although evf_ newsletter care will be exercised when return is requested. Please addni all contributions to the Editor at 80 Bannockburn Avenue, Torom: Ontario MSM 2N1. All other Society business, including membership inquiries, shoi Number 324, January 1973. be addressed to the Society at Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto, Or: ario M5W 1A2. Members are asked to give the Society at least ft weeks' notice of address changes. Upper Canada Railway Society Reproduction of the contents of this magazine is prohibited witkifty years a the written permission of the Society. of a new ••^^^•HHHHI^^^^^HI^MHHHMaaa^MMHa^HHHHI^BHBHHHMn em and ten d f Canada war ailway enter ational Rail omponents, t RAILWAY NEWS AND COMMENT ay system on ears later, he two acts 1972 A RECORD YEAR OF GROWTH FOR CANADIAN NATIONAL CN passenger trains carried approximately 12-million ireation of £ enue passengers during the year. Deluxe coach acconir:orporated or The following is the text of the year-end statement by ation, marketed as Dayniter cars, and an experimentalhe name Canr Canadian National Chairman and President Norman J. Mac- that allows passengers to take their automobiles witiecreed on Df Mi 11 an, issued on the last day of 19 72: on the same train between Edmonton and Toronto, were ictors for tl reduced. -

First Monday Toy Auction 5Th December 2011 CATALOGUE

First Monday Toy Auction 5th December 2011 CATALOGUE 1 LOT 1 Hornby O-gauge LMS Brake van. No box, some slight rust on edge of roof & one corner of body, some paint missing from roof, good. Starts at: $10 LOT 2 Hornby O-gauge goods platform with box with torn corner of lid, but generally good. Platform has some surface rust, tin printed walls are very good, roof has slight crease, very good. Starts at: $60 LOT 3 Hornby O-gauge No. 2 Pullman. Has replacement windows, very slight dent on roof, one mansell wheel is cracked, good/very good. Starts at: $80 LOT 4 Hornby O-gauge Southern Milk Traffic Van. Box fair/good, missing one flap. Van roof is bent on one corner. Wheels are plastic. Condition, very good. Starts at: $20 LOT 5 Hornby O-gauge Metropolitan Coach. Roof has very slight dents & has been repainted. There are slight scratches on body. Condition, very good. Starts at: $150 LOT 6 Hornby O-gauge No. 1 clockwork LMS 623 tank loco circa 1926. Motor works, but needs some TLC, cab is slightly distorted, front coupling is broken, front right hand buffer is missing. No box. Condition, fair. Starts at: $30 2 LOT 7 Hornby O-gauge 6x metal signs: York, Newcastle, Edinburgh, Grantham, Kings Cross, Doncaster, Paint chipped, Condition, fair only Starts at: $20 LOT 8 Marklin Gauge-1 Steeplecab electric 0-4-0 3-rail loco. No box Condition, fair/good. Starts at: $650 LOT 9 Magazine ‘The Railway Modeller’ Nov. 1951. Small piece torn out of back page, otherwise excellent. -

RSD4J5 • COMING SOON Two NEW BOOKS from ROCKY Mountain PUBLISHING, INC

IDGIlliGHTS OF TIDSISSUE: • Freelancing!Part 1- DevelopingGuidelines • ConrailsD40s and How toModel Them • VermontRailway Diesels • • Wood-Sided 19J7 AAR Boxcars • OUtdoorModel Photography • On TRACK:Vertical Curves • PrototypeModeling in G Gauge • • TwentyYears and Countingon the DT&R • Norfolk andWestern's Pond Creek Colliery • DieselDetaiJ: Railway Utah RSD4J5 • COMING SOON tWO NEW BOOKS FROM ROCKY MOUNtAIN PUBLISHING, INC. MODEL RAILROADING'S GUIDE TO THE RAILWAY EXPRESS, by V. S. Roseman Available Late Spring 1992 • Approximately 100 Pages • $12.95 retail A comprehensive study of the Railway Express Agency... its history, equipment, practices and operations. During the days when "Travel by Train" was the norm, REA was "the" way to ship it. Author V. S. Roseman follows REA up through its final days. Also includes specific information for modeling REA. • • • MODEL RAILROADING'S GUIDE TO THE NORFOLK AND WESTERN RAILWAY: WILLIAMSON TERMINAL -1953, by Vern french Available Late Spring 1992 • 100+ Pages • $12.95 retail A must-have book for N&W historians and modelers alike. Author Vern French chronicles the story of Williamson and his modeling of it. Includes comprehensive information on N&W motive power; freight, passenger and MoW rolling stock; and closely examines the facilities and operations at Williamson, WV, circa 1953. June 199� VOLUME 22 NUMBER 6 Photo by David A. Bontrager FEATURES 14 MODELING FROM THE PROTOTYPE WITH BACHMANN'S G GAUGE KITS by Chris Lane 17 ON TRACK: VERTICAL CURVES by Jim Mansfield 18 ADVENTURES WITH LAYOUTS: REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST - PART II by Larry Smith 22 TWENTY YEARS AND COUNTING ON THE DT&R by Larry Puckett 26 BEHlND THE SCENES: AT CORN JUNCTION - PART 3 by Margaret Mansfield 28 OPERATIONS PLANNING FOR OPERATION - PART THREE: TRAIN SCHEDULING by Jim Mansfield 32 FREELANCING! PART I - DEVELOPING GUIDELINES by David A. -

Newsletter Upper Canada Railway Society EDITOR - Robert D

newsletter Upper Canada Railway Society EDITOR - Robert D. McMann CONTRIBUTING EDITORS - Charles 0. Begg John D. Thompson Michael W. Roschlau NEWSLETTER is published monthly by the Upper Canada Railway Society Inc., Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto 115, Ontario. Contributions to the NEWSLETTER are solicited. No responsibility can be assumed for loss or non-return of material, although every newsletter care will be exercised when return is requested. Please address all contributions to the Editor at 80 Bannockburn Avenue, Toronto 380, Ontario. All other Society business, including membership inquiries, should Number 317, June 1972. be addressed to the Society at Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto 116, Ontario. Members are asked to give the Society at least five weeks' notice-of address changes. Upper Canada Railway Society Reproduction of the contents of this magazine is prohibited without the written permission of the SOcpety. •:.^^^^x^•:•^:•^^^^^^:•:•^:w^^^x•Xw^v^<.^:%.^^^ RAILWAY NEWS AND COMMENT CANADIAN NATIONAL EXECUTIVE APPOINTMENTS Prior to his new appointment, Mr. Richer was vice-pres• Appointment of three executive vice-presidents at the ident for the St. Lawrence Region of CN. He joined the corporate headquarters of Canadian National Railways company in 1962 as special assistant to the vice-pres• was announced in Montreal April 11th by N. J. MacMillan, ident of the region, and soon after became assistant Chairman and President. manager of the company's Montreal area. He served as manager of the Champlain area from 1963 to 1965 before They are Dr. R. A. Eandeen, former vice-president. Great being named vice-president of passenger sales. Born lakes Region, who becomes executive vice-president, fin• in Montreal, he is a graduate of Jean De Brebeuf College, ance and administration; Jean H. -

SVLS 2004 Spring Meet

www.svls.org JUNE 2004 Volume 31, Issue 06 SVLS 2004 Spring Meet Don Cure Registration Rick Zobelein joe Yetter & Craig Craddock Henry Aguirre Don Yungling bays June 2004 The Golden Spike Page 2 CALENDAR MEMBERSHIP By Lorra Fowlar June 5 Club run day (public rides noon to 4) June 9 Rancho Cordova Fourth of July Committee WELCOME NEW MEMBERS meeting will be Wednesday, June 9th at 6:30 pm at the Rockingham Sheriffʼs Station David and Lisa Brenner; Vacaville Gary Landeen; Sacramento (Public Meeting Room, 10361) Dave and Mary Fontes; Rohnert Park David Sander, Chairman Edward Marsh; Fresno June 10 Board Meeting 6:30 Park room Tom and Lisa Philp; Carmichael June 18 General Membership Meeting Ben Schack; Rio Linda 7:30 Hagan Park meeting room June 19 Club Work Day - everyone come help June 20 Club run day (public rides noon to 4) June 21 News letter deadline. Please add these renewals to your 2004 roster Warren Sharratt July 3 & 4 4th Mini Meet - Bring your train Steve Alley Public rides noon to 4 each day Francis and Bev Simoneau July 8 Board Meeting 6:30 Park room Pam and Robert Naylor July 16 General Membership Meeting Donald and Toyoko Yungling 7:30 Hagan Park meeting room July 17 Club Work day - all members invited July 18 Club run day (public rides noon to 4) July 19 News letter deadline Donʼt forget about work days, every Tuesday and most Saturdays. Contact a committee member for information on needs. There are always things to be done to support YOUR club. -

Download Newsletter

WJVintage November 2020 Newsletter Welcome to the November 2020 edition of the WJVintage newsletter. It hardly seems possible that Christmas is just around the corner and yet we are still in the grip of the Covid 19 pandemic and indeed, here in England, we are midway through a proposed/supposed one month second lockdown. Fortunately, this is another bumper edition so at least you can while away a nice coffee break with something to read! I must just mention that this is not a bumper edition due to my travels, as I haven’t been anywhere! No, once again I have you, the readership, to thank for your wonderful contributions which allow me to bring you a varied, and hopefully interesting, view of what everyone is up to during this strange year on planet earth. Please, please keep the photos, snippets of information and articles coming as I think we are going to be largely stuck at home for some time to come. Thanks to David Knighton for this month’s header photo – there’s more from him below. So, this month ‘Customer Corner’ is very definitely worth a visit with layout photos from several readers, Part 2 of Roger Kimber’s Collection, featuring his British outline models and a superb feature on DIY Cattle/Livestock Wagons from Andrew Spooner. If he could ‘kit’ his design I think it would be very popular, so do take a look! ‘What’s New’ features a superb new Well Wagon, which is our first 2021 new product announcement, plus I have included my ‘Christmas Crackers’, a range of goodies I have arriving imminently and/or already in stock and available to tempt you as Christmas presents or treats! Stay safe and …. -

Railway Museum Q U a R T E R L Y

Railway Museum q u a r t e r l y "Advancing Railway Preservation" Number 54 A Journal of the Association of Railway Museums Winter 2010 The 2010 ARM Conference featured a trip over the spectacular ex-BC Rail line on the Whistler Mountaineer to Whistler Mountain resort. West Coast Railway Association’s Canadian Pacific heavyweight mountain observation car #598 runs in the consist, providing revenue to the association and a great way to view the railroad. Jim Vaitkunas photo. PRESIDENT’S COLUMN railway By Bob LaPrelle As we settle into a new year, thanks are in order to several organizations and museum individuals for a job well done in 2009. First and foremost, a big thanks to our members for their continued support of ARM. Your membership quarterly enables the organization to represent the railway preservation community with the collective strength of all of us. As you will read elsewhere in this issue Railway Museum Quarterly is published quarterly by the Association of Railway Museums and of RMQ, association and collaboration distributed free of charge to member and affiliate member institutions and individuals. The are key to tackling our challenges that opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the Association. Articles appearing in RMQ lie ahead. may be reprinted in whole or in part provided proper credit is given the source. Submissions are I would also like to thank our host always welcomed, along with accompanying photos. Articles covering programs, initiatives, major site for a great Fall 2009 Conference. events and undertakings of member institutions are of special interest. -

Railway Museum Q U a R T E R L Y

Railway Museum q u a r t e r l y "Advancing Railway Preservation" Number 51 A Journal of the Association of Railway Museums Spring 2009 An invitation received at the ARM 2008 Conference inspired the Editor to visit the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History, a growing ARM member in Kennesaw, GA. It’s home to the General (Rogers 1855), the Civil War’s most famous locomotive. For more on Georgia railway preservation, see page 4. Aaron Isaacs photo. EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR'S LETTER railway By Suzanne Grace Each time I attend an ARM Board of museum Directors meeting, I am again impressed with the progressive leadership of the association. It is refreshing to observe a board whose members work solely for quarterly the benefit of the organization with no self-interest and in full cooperation with one another. There is, of course, no remuneration for ARM board members. Railway Museum Quarterly is published quarterly by the Association of Railway Museums and Although much is expected of them, the distributed free of charge to member and affiliate member institutions and individuals. The work is strictly voluntary. opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the Association. Articles appearing in RMQ Each meeting begins with a review of may be reprinted in whole or in part provided proper credit is given the source. Submissions are the association’s strategic plan. This always welcomed, along with accompanying photos. Articles covering programs, initiatives, major document is a living plan for the events and undertakings of member institutions are of special interest. -

August, 1974 Ne "

T E AUGUST, 1974 NE " ... the intent behind the creation of our department was to provide greater coordination and assistance in the planning activities in all The departments." Corporate Planning Department G. A. Kellow Vice President- Corporate Planning In an article which appeared previously in this maga ditions. In a very real sense, planning involves a delicate zine, President Smith stated what he considered to be balance between short term commitments and long term the most important objectives of the Milwaukee Road. flexibility. These objectives bear repeating. They are: There are several types of planning. COMPREHEN 1) Provide the level and quality of total service nec SIVE planning involves the constant formulation of ob essary to retain existing positions in transportation mar jectives and the guidance of the company's activities kets and provide a base to profitably expand the railroad's toward their attainment. Comprehensive planning calls participation in existing and in new markets. for a total evaluation of the company's operations as well 2) Maximize utilization of assets, eliminating those as its potential. This kind of overview is one of the areas not required for present and future needs, and concen in which the corporate planning staff can play an im trating available resources toward activities that have portant role. present and future strategic purpose. A second type of planning, called FUNCTIONAL, 3) Establish and maintain a responsibility budgeting has to do with the individual elements of a total problem. and control system encompassing all departments and Functional planning focuses on how each part can best subsidiaries to provide proper control of all activities. -

Hornby Dublo 3-Rail

21st June Trains Text.qxp 03/06/2019 13:50 Page 1 Vectis Auctions, Vectis Auctions, Fleck Way, Thornaby, Oxford Office, Stockton-on-Tees, TS17 9JZ. Unit 5a, West End Industrial Estate, Telephone: 0044 (0)1642 750616 Witney, Oxon, OX28 1UB. Fax: 0044 (0)1642 769478 Telephone: 0044 (0)1993 709424 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vectis.co.uk MODEL TRAIN SALE Friday 21st June 2019 AUCTION COMMENCES AT 10.30am Room and Live On-Line Auctions at Thornaby, Stockton-on-Tees, TS17 9JZ. Viewing available on the day of the Sale from 8.00am. Bidding can be made using the following methods: Commission Bids, Postal/Fax Bids, Telephone Bidding - If you intend to bid by telephone please contact our office for further information on 0044 (0)1642 750616. Internet Bidding - you can bid live on-line with www.vectis.co.uk or www.invaluable.com. You can also leave proxy bids at www.vectis.co.uk. If you require any further information please contact our office. FORTHCOMING AUCTIONS Specialist Sale Tuesday 9th July 2019 Specialist Sale Wednesday 10th July 2019 Civilian Figures, Vehicles, Accessories & General Toy Sale Thursday 11th July 2019 Model Train Sale Friday 19th July 2019 TV & Film Related Sale Tuesday 30th July 2019 Details correct at time of print but may be subject to change, please check www.vectis.co.uk for updates. Managing Director Vicky Weall Cataloguers Michael Bond & Mike Delaney Photography Paul Beverley & Andrew Wilson Data Input Patricia McKnight & Andrea Rowntree Layout & Design Andrew Wilson & Simon Smith A subsidiary of The Hambleton Group Ltd - VAT Reg No. -

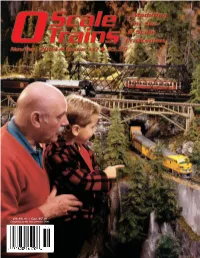

US $5.95 • Can $7.95 Display Until December 31St Empireempire Builderbuilder 2-Rail O Scale with Sound and More!

US $5.95 • Can $7.95 Display until December 31st EmpireEmpire BuilderBuilder 2-Rail O Scale with Sound and More! Great Northern 4-8-4 S-2 2-Rail Steam Locomotive w/Proto-Sound® 2.0 20-3145-2 Cab No. 2584 $1,199.95 Great Northern 4-8-4 S-2 2-Rail Steam Locomotive w/Proto-Sound® 2.0 20-3146-2 Cab No. 2587 $1,199.95 Scale modelers can celebrate the 75th Year O of the Empire Builder with this limited release of the S-2 Northern - exclusively from M.T.H. Electric Trains. Outfitted with industry-leading features and performance, the S-2 is available in two cab numbers Be one of the FIRST to own a 2-RAIL2-RAILlocomotive and is sold in both 2-rail scale and 3-rail hi-rail ver- with all of these incredible features..... sions. Both versions include our latest feature, found only in M.T.H. Premier Line locomotives, Proto-Scale Superior patented synchronized puffing smoke 32™ which allows the user to configure in minutes Superior patented locomotive speed control that really either model for use on 2-rail or 3-rail track. works in conventional or command mode Patented Proto-Scale 3-2™ for quick conversion to and Fully outfitted with the power and performance of from 2 and 3-rail operation Proto-Sound 2.0, the S-2 Northern is the second Unique digital sound features including squeaking Premier Line 2-rail steam locomotive to ship with synchronized puffing smoke, Proto-Speed control for brakes, Doppler, train wreck, clickty-clack and much more incredible slow speed action and the industry's most Unsurpassed value in conventional or command operation realistic digital sound system. -

Lagazine of the PACIFIC ELECTRIC RAILWAY

lagazine of the PACIFIC ELECTRIC RAILWAY Registered at the G.P.O., Sydney, for APRIL 1966 transmission by post as a periodical. TWENTY FIVE CENTS 2 TROLLEY WIRE APRIL 1966 COMING TO MELBOURNE? We invite you to join us on the Labour Day long weekend for a fascinating tour of railways and tramways in Victoria. The following is a brief outline of our timetable. SATURDAY 1st OCTOBER: Arrive Melbourne 9.00 a.m. on "Southern Aurora"; morning tram tour; special two-car swing door electric train to Belgrave; re turn trip to Emerald on "Puffing Billy"; then back to Melbourne for an evening tram tour. SUNDAY 2nd OCTOBER: By vintage steam train to Ballarat,hauled by one of the now-rare "R" class engines; all-lines tour of Ballarat; then return to Melbourne with steam. MONDAY 3rd OCTOBER: Special diesel electric rail motor to Bendigo; all-lines tour of Bendigo feat uring Birney cars; return to Melbourne in time for 8.00 p.m. departure on "Southern Aurora". This schedule has something for everyone, with a full coverage of the Ballarat and Bendigo systems; a glimpse of the Melbourne tramways; Australia's most unique electric trains; and both narrow and broad gauge steam including the 70 mph Geelong speed way route. The fare is not yet determined but you can book without obligation by paying a deposit of $10.00. Please book early as it will be diffi cult to include latecomers in the party. Book Now! Send your deposit today to: Southern Division, S.P.E.R., Box 103, G.P.O., SYDNEY.