Foot Strike and Injury Rates in Endurance Runners: a Retrospective Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

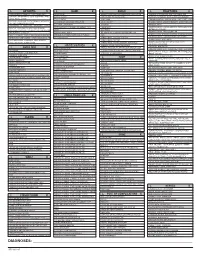

ICD-10 Diagnoses on Router

L ARTHRITIS R L HAND R L ANKLE R L FRACTURES R OSTEOARTHRITIS: PRIMARY, 2°, POST TRAUMA, POST _____ CONTUSION ACHILLES TEN DYSFUNCTION/TENDINITIS/RUPTURE FLXR TEN CLAVICLE: STERNAL END, SHAFT, ACROMIAL END CRYSTALLINE ARTHRITIS: GOUT: IDIOPATHIC, LEAD, CRUSH INJURY AMPUTATION TRAUMATIC LEVEL SCAPULA: ACROMION, BODY, CORACOID, GLENOID DRUG, RENAL, OTHER DUPUYTREN’S CONTUSION PROXIMAL HUMERUS: SURGICAL NECK 2 PART 3 PART 4 PART CRYSTALLINE ARTHRITIS: PSEUDOGOUT: HYDROXY LACERATION: DESCRIBE STRUCTURE CRUSH INJURY PROXIMAL HUMERUS: GREATER TUBEROSITY, LESSER TUBEROSITY DEP DIS, CHONDROCALCINOSIS LIGAMENT DISORDERS EFFUSION HUMERAL SHAFT INFLAMMATORY: RA: SEROPOSITIVE, SERONEGATIVE, JUVENILE OSTEOARTHRITIS PRIMARY/SECONDARY TYPE _____ LOOSE BODY HUMERUS DISTAL: SUPRACONDYLAR INTERCONDYLAR REACTIVE: SECONDARY TO: INFECTION ELSEWHERE, EXTENSION OR NONE INTESTINAL BYPASS, POST DYSENTERIC, POST IMMUNIZATION PAIN OCD TALUS HUMERUS DISTAL: TRANSCONDYLAR NEUROPATHIC CHARCOT SPRAIN HAND: JOINT? OSTEOARTHRITIS PRIMARY/SECONDARY TYPE _____ HUMERUS DISTAL: EPICONDYLE LATERAL OR MEDIAL AVULSION INFECT: PYOGENIC: STAPH, STREP, PNEUMO, OTHER BACT TENDON RUPTURES: EXTENSOR OR FLEXOR PAIN HUMERUS DISTAL: CONDYLE MEDIAL OR LATERAL INFECTIOUS: NONPYOGENIC: LYME, GONOCOCCAL, TB TENOSYNOVITIS SPRAIN, ANKLE, CALCANEOFIBULAR ELBOW: RADIUS: HEAD NECK OSTEONECROSIS: IDIOPATHIC, DRUG INDUCED, SPRAIN, ANKLE, DELTOID POST TRAUMATIC, OTHER CAUSE SPRAIN, ANKLE, TIB-FIB LIGAMENT (HIGH ANKLE) ELBOW: OLECRANON WITH OR WITHOUT INTRA ARTICULAR EXTENSION SUBLUXATION OF ANKLE, -

Fibular Stress Fractures in Runners

Fibular Stress Fractures in Runners Robert C. Dugan, MS, and Robert D'Ambrosia, MD New Orleans, Louisiana The incidence of stress fractures of the fibula and tibia is in creasing with the growing emphasis on and participation in jog ging and aerobic exercise. The diagnosis requires a high level of suspicion on the part of the clinician. A thorough history and physical examination with appropriate x-ray examination and often technetium 99 methylene diphosphonate scan are re quired for the diagnosis. With the advent of the scan, earlier diagnosis is possible and earlier return to activity is realized. The treatment is complete rest from the precipitating activity and a gradual return only after there is no longer any pain on deep palpation at the fracture site. X-ray findings may persist 4 to 6 months after the initial injury. A stress fracture is best described as a dynamic tigue fracture, spontaneous fracture, pseudofrac clinical syndrome characterized by typical symp ture, and march fracture. The condition was first toms, physical signs, and findings on plain x-ray described in the early 1900s, mostly by military film and bone scan.1 It is a partial or incomplete physicians.5 The first report from the private set fracture resulting from an inability to withstand ting was in 1940, by Weaver and Francisco,6 who nonviolent stress that is applied in a rhythmic, re proposed the term pseudofracture to describe a peated, subthreshold manner.2 The tibiofibular lesion that always occurred in the upper third of joint is the most frequent site.3 Almost invariably one or both tibiae and was characterized on roent the fracture is found in the distal third of the fibula, genograms by a localized area of periosteal thick although isolated cases of proximal fibular frac ening and new bone formation over what appeared tures have also been reported.4 The symptoms are to be an incomplete V-shaped fracture in the cor exacerbated by stress and relieved by inactivity. -

Q & A: Running Injuries Show Notes

Q & A: Running Injuries Show Notes I was told I have multiple imbalances in one leg. One was tight ankles. My question would just be how does multiple imbalances happen? Is it genetic or is it just something that happens from injury? -Johari • Imbalances can be genetic. There are many different structural anomalies found in individuals. • Most imbalances are from chronic poor posture: o Poor sitting posture. o Poor standing posture. o Asymmetries with common movement patterns. For example only crossing your left leg, or always sitting on the couch with your legs tucked under one direction. • Spot train the imbalances and asymmetries as best you can. Work toward gaining symmetry in the body. • Small changes over time will yield big results. Would love to hear about "sleeping" glutes and what can be done to reawaken them! -Britt • Most common cause is chronic sitting. • Poor posture from either standing or sitting. • The treatment is to move more. Not to just stand more (although that is better than sitting), but move more. Focus on activities that activate the posterior chain such as squats, deadlifts, and bridges. • Increase the neural input to the glutes. The more you use them, the more the neural pathways will be established and re-enforced. • Encourage everyone to address his/her glute strength as they are typically weak in most individuals. As part of cross training, implement core strengthening which will help to prevent low back pain. For more information, please refer to: http://marathontrainingacademy.com/low-back-pain http://www.thephysicaltherapyadvisor.com/2014/10/20/how-to-safely-self-treat-low-back-pain/ http://www.thephysicaltherapyadvisor.com/2014/06/30/my-top-7-tips-to-prevent-low-back-pain- while-traveling/ © 2016, The Physical Therapy Advisor www.thePhysicalTherapyAdvisor.com I have a partially torn tendon in the gluteus medius that attaches to the greater trochanter. -

Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Doctor of Physical Therapy Research Papers Physical Therapy 3-2012 Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome Scott Darling St. Catherine University Hannah Finsaas St. Catherine University Andrea Johnson St. Catherine University Ashley Takekawa St. Catherine University Elizabeth Wallner St. Catherine University Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/dpt_papers Recommended Citation Darling, Scott; Finsaas, Hannah; Johnson, Andrea; Takekawa, Ashley; and Wallner, Elizabeth. (2012). Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/dpt_papers/17 This Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Physical Therapy at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Physical Therapy Research Papers by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RISK FACTORS FOR PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME by Scott Darling Hannah Finsaas Andrea Johnson Ashley Takekawa Elizabeth Wallner Doctor of Physical Therapy Program St. Catherine University March 7, 2012 Research Advisors: Assistant Professor Kristen E. Gerlach, PT, PhD Associate Professor John S. Schmitt, PT, PhD ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is a common source of anterior knee in pain females. PFPS has been linked to severe pain, disability, and long-term consequences such as osteoarthritis. Three main mechanisms have been proposed as possible causes of PFPS: the top-down mechanism (a result of hip weakness), the bottom-up mechanism (a result of abnormal foot structure/mobility), and factors local to the knee (related to alignment and quadriceps strength). The purpose of this study was to compare hip strength and arch structure of young females with and without PFPS in order to detect risk factors for PFPS. -

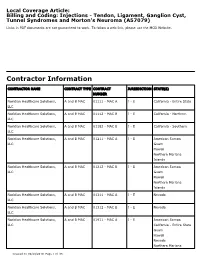

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

For Distance Runners Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome Is the Second

BIOMECHANICAL INJURY PREDICTORS FOR MARATHON RUNNERS : STRIDING TOWARDS ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME INJURY PREVENTION John M. MacMahon, Ajit M. Chaudhari and Thomas P. Andriacchi Stanford Biomotion Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, California The purpose of this study was to prospectively analyze a large group of marathon runners (n=20) and test for biomechanical determinants of running injuries. The opportunity to prospectively follow runners of organized marathon training teams allowed for testing of the hypothesis that functional biomechanics may lead to iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS). Each runner was gait tested prior to developing any injuries. Injury predictors were generated by comparing those legs which eventually got ITBS injuries (n=7) with those legs that were injury free (n=33). Higher peak hip adduction moments (p<0.05) and higher angular impulses adducting the hip during stance phase (p<0.005) were found to be significant predictors of ITBS. With this prognostic test as a benchmark, training and coaching may produce dynamic injury prevention. KEY WORDS: injury prediction, injury prevention, running injuries, iliotibial band, training techniques INTRODUCTION: The rigor of the marathon is legendary. In 490 BC, the runner Pheidippides ran from Marathon with news of the Greek victory over the Persians, stood on the steps of the Acropolis in Athens and shouted, "Rejoice, we conquer!" and then dropped dead. Less severe injuries await today's marathoner. Nonetheless, marathon running is growing in popularity around the world. With the global dose of Olympic glory about to be dispensed in Sydney this summer, this trend should be expected to increase. Many of these running injuries are due to the repetitive nature of training. -

Chronic Running Injuries

High Performance Services: Physiotherapy / chronic running PREDISPOSING FACTORS Overuse injuries have been linked with abnormal lower limb biomechanics. There are three main injuries biomechanical abnormalities affecting the lower limb contributing to chronic injuries: Text: Carien Ferreira, BSc. Physio (US)and Anelize Usher, BSc. Physio (UFS) 1. Excessive pronation (rolling in on the mid foot) This is when, either the ankle pronates (turns in) excessively, or when the foot fails to return to the unners often wind up with injuries without any ‘supinated’ (turned up) position between strikes. Impact obvious traumatic event to cause an injury. Most whilst the foot is in this ‘weakened’ position will place of these are the result of a wide variety of factors extra stress on ligaments and muscles of the lower leg. Rthat over time lead to chronic problems. These This can cause an abnormal flattening of the medial chronic injuries may be caused by repetitive use, stress longitudinal arch of the foot leading to increased and trauma to the soft tissues of the body (muscles, strain on the plantar fascia. Adaptive shortening of the tendons, bones and joints) without allowing enough iliotibial band will cause an ‘overuse’ of the dorsiflexors rest and recovery. They begin as a small, nagging ache of the ankle (gastroc., soleus, tibialis posterior) thereby or pain, and can grow into a debilitating injury if they leading to an increased risk of tendinitis. Since the foot aren’t treated early and correctly. is ‘unstable’ the risk of stress fractures due to uneven Although running is undoubtedly one of the best ways distribution is increased. -

Patellofemoral SMCA 2014 Handout

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome / How can a Sesamoid Bone Anterior Knee Pain / Runners’ Knee cause So Many Problems? _ n Most common cause of Patellofemoral Pain and knee pain Patella Instability n Most common symptom presenting to SM n Diagnostic challenge n Treatment controversies n Lack of evidence to support Sarah Kerslake BPHTY Ax and Rx PFPS Patellofemoral Anatomy n Multifactorial Etiology n Considering the PF joint is one of the most n Non-operative treatment is successful highly loaded joints in the human body, the prevalence of AKP is not surprising. n Strong evidence supports treatment with multimodal therapy n Anatomy: n Sesamoid bone in extensor apparatus n Routine clinical Ax of muscle strength in athletes may not detect deficits n Acts as pulley/cam in extensor mechanism n Protects the tibiofemoral joint n More challenging functional tests required n Anchored by Active and Passive elements PFPS Anatomy PFPS Anatomy n Active (Dynamic) restraints n Passive (Static) restraints n Quadriceps muscle n Bony anatomy (Facets <=> Trochlea) n Vastus Lateralis Obliquus/Longus n Quadriceps Fascia + Patellar Tendon n Rectus Femoris + Vastus Intermedius n Lateral Peripatellar Retinaculum n Vastus Medialis Obliquus/Longus n Medial Peripatellar Retinaculum, particularly n Patella Tendon the medial patellofemoral ligament n Iliotibial band n Balance between structures is v. important 1 PFPS Symptoms PFPS Pathology n Symptoms include pain, swelling, n Patellar Tracking weakness, instability, mechanical n Patellar Tendinopathy symptoms & functional -

Plica: Pathologic Or Not? J

Plica: Pathologic or Not? J. Whit Ewing, MD Abstract A fold that occurs within a joint is referred to as a plica synovialis. Three such pli- in which the only finding to explain cae are seen with regularity within the human knee joint. These folds are normal the symptoms is the presence of a structures that represent remnants of mesenchymal tissue and/or septa formed thickened, hypertrophic plica. during embryonic development of the knee joint, and can be seen during arthro- Chronic anteromedial knee pain and scopic inspection of the knee joint. Controversy exists within the orthopaedic com- a sense of tightness in the subpatellar munity as to whether a plica can develop pathologic changes sufficient to cause region on squatting are the common disabling knee symptoms. The author defines the clinical syndrome, describes the complaints expressed by patients arthroscopic appearance of pathologic plica, and outlines nonsurgical and surgi- found to have a pathologic plica. The cal methods of management of this uncommon condition. ligamentum mucosum is not a J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1993;1:117-121 source of these types of symptoms. Additional symptoms are snapping sensations, buckling, knee pain on A plica synovialis is a membranous commonly referred to as a medial shelf sitting, and pain with repetitive fold or ridge found in the synovial or medial plica. This shelflike fold of activity.4 Recurrent effusions and lining of a joint. Three such folds are synovial membrane extends from the locking of the knee joint are not typi- found with regularity in the human infrapatellar fat pad to the medial wall cal in patients with this syndrome. -

Sports Specific Safety Cross Country Running

Sports Specific Safety Cross Country Running Sports Medicine & Athletic Related Trauma SMART Institute © 2010 USF Objectives of Presentation 1. Identify the prevalence of injuries to cross- country runners. 2. Discuss commonly seen injuries in these athletes. 3. Provide information regarding the management of these injuries. 4. Provide examples of venue and equipment safety measures. 5. Provide conditioning tips to reduce potential injuries © 2010 USF Injury Statistics • 65% of all runners will be injured in any year. • For every 100 hours of running, the average runner will sustain 1 running injury. • The average runner will miss about 5-10 per cent of their workouts due to injury each year. • Novice runners are significantly MORE likely to be injured than individuals who have been running for many years. • Only 50% of these injuries are new – the rest are recurrences of previous problems. © 2010 USF Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 149(11), pp. 2561-8, 1989 Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 25(5), p. S81, 1993 American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 16(3), pp. 285-294, 1988. Commonly Seen Injuries By far the most common running injuries are overuse injuries due to improper training. • Anterior knee pain syndrome – Runner's Knee • Iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome • Shin splints • Achilles tendonitis • Plantar Fasciitis © 2010 USF Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome • Cause of Injury – Repetitive/overuse conditions – Mal-alignment – Weakness – Poor flexibility – Joint ‘looseness’ • Signs of Injury – Pain over front of knee -

Diagnosing & Treating Non-Traumatic Knee Pain

ORTHOPEDIC PRIMARY CARE: Diagnosing & Treating Non-Traumatic Knee Pain © Jackson Orthopaedic Foundation www.jacksonortho.org Acknowledgement This lecture was originally developed as part of Orthopedic Primary Care, a six-month continuing education program presented yearly by the Jackson Orthopaedic Foundation, a non-profit organization in Oakland, California. More information at: OrthoPrimaryCare.Info www.jacksonortho.org Disclosure Statement of Unapproved/Investigative Use • This presentation contains no discussion of the unapproved/investigative use of any commercial product or device. www.jacksonortho.org Disclosure Statement of Financial Interest Neither Dr. Benham nor Dr. Geier has any financial interests/arrangements or affiliations with one or more organizations that could be perceived to have real or apparent conflicts of interest in the context of the subject of this presentation. www.jacksonortho.org Learning Objectives • At the conclusion of this presentation, participants will be able to 1. Identify likely causes of non-traumatic, non-arthritic knee pain based on presentation and history. 2. Appropriately apply specialty exam techniques and order diagnostic imaging as needed to definitively diagnose non-traumatic, non-arthritic knee pain. 3. Implement appropriate treatment plans to include integrative and pharmaceutical modalities. The use and effects of the following pharmaceutical types will be discussed: acetaminophen, NSAIDs, injectable corticosteroids and topical analgesics. www.jacksonortho.org Learning Objectives • At the conclusion of this presentation, participants will be able to 1. Identify likely causes of non-traumatic, non-arthritic knee pain based on presentation and history. 2. Appropriately apply specialty exam techniques and order diagnostic imaging as needed to definitively diagnose non-traumatic, non-arthritic knee pain. -

Iliotibial Band Syndrome: a Common Source of Knee Pain RAZIB KHAUND, M.D., Brown University School of Medicine, Providence, Rhode Island SHARON H

Iliotibial Band Syndrome: A Common Source of Knee Pain RAZIB KHAUND, M.D., Brown University School of Medicine, Providence, Rhode Island SHARON H. FLYNN, M.D., Oregon Medical Group/Hospital Service, Eugene, Oregon Iliotibial band syndrome is a common knee injury. The most common symptom is lateral knee pain caused by inflammation of the distal portion of the iliotibial band. The iliotibial band is a thick band of fascia that crosses the hip joint and extends distally to insert on the patella, tibia, and biceps femoris tendon. In some athletes, repetitive flexion and extension of the knee causes the distal iliotibial band to become irritated and inflamed resulting in diffuse lateral knee pain. Iliotibial band syndrome can cause significant morbidity and lead to cessation of exercise. Although iliotibial band syndrome is easily diagnosed clinically, it can be extremely challenging to treat. Treatment requires active patient participation and compliance with activity modifica- tion. Most patients respond to conservative treatment involving stretching of the iliotibial band, strengthening of the gluteus medius, and altering training regimens. Corticosteroid injections should be considered if visible swelling or pain with ambulation persists for more than three days after initiating treatment. A small percentage of patients are refractory to conservative treatment and may require surgical release of the iliotibial band. (Am Fam Physician 2005;71:1545-50. Copyright© American Academy of Family Physicians.) See page 1465 for liotibial band syndrome is a common it slides over the lateral femoral epicondyle strength-of-evidence knee injury that usually presents as lat- during repetitive flexion and extension of labels.