Your Blues Ain't Like Mine, but We All Hide Our Faces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Bob Denson Master Song List 2020

Bob Denson Master Song List Alphabetical by Artist/Band Name A Amos Lee - Arms of a Woman - Keep it Loose, Keep it Tight - Night Train - Sweet Pea Amy Winehouse - Valerie Al Green - Let's Stay Together - Take Me To The River Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You - Girl on Fire - No One Allman Brothers Band, The - Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More - Melissa - Ramblin’ Man - Statesboro Blues Arlen & Harburg (Isai K….and Eva Cassidy and…) - Somewhere Over the Rainbow Avett Brothers - The Ballad of Love and Hate - Head Full of DoubtRoad Full of Promise - I and Love and You B Bachman Turner Overdrive - Taking Care Of Business Band, The - Acadian Driftwood - It Makes No Difference - King Harvest (Has Surely Come) - Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, The - Ophelia - Up On Cripple Creek - Weight, The Barenaked Ladies - Alcohol - If I Had A Million Dollars - I’ll Be That Girl - In The Car - Life in a Nutshell - Never is Enough - Old Apartment, The - Pinch Me Beatles, The - A Hard Day’s Night - Across The Universe - All My Loving - Birthday - Blackbird - Can’t Buy Me Love - Dear Prudence - Eight Days A Week - Eleanor Rigby - For No One - Get Back - Girl Got To Get You Into My Life - Help! - Her Majesty - Here, There, and Everywhere - I Saw Her Standing There - I Will - If I Fell - In My Life - Julia - Let it Be - Love Me Do - Mean Mr. Mustard - Norwegian Wood - Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da - Polythene Pam - Rocky Raccoon - She Came In Through The Bathroom Window - She Loves You - Something - Things We Said Today - Twist and Shout - With A Little Help From My Friends - You’ve -

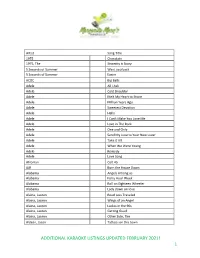

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

The Wonder of Not Knowing Rabbi Toba Spitzer I Wanted to Share with You a Piece That Appeared in the Boston Globe a Few Years Ag

The Wonder of Not Knowing Rabbi Toba Spitzer I wanted to share with you a piece that appeared in the Boston Globe a few years ago, by Joan Wickersham. It’s called “Too Much Information”: AT A recent dinner with friends, someone was telling a story about taking her teenage kids to New York, where they’d stumbled into a store so cool that she hadn’t been able to figure out the name of it. “Uniqlo? Uniglo? It had one of those beautiful, unreadable logos. Anyway —’’ she said; but we never got to hear the rest of the story, because someone at the table had whipped out an iPhone and was making a big production of looking up the name of the store. “Uniglo,’’ the looker-upper announced triumphantly (and erroneously). “Ah,’’ we all murmured. The conversation died. Why couldn’t the poor woman have been allowed to simply tell her story? Why this reluctance to let even the smallest, most whimsical question remain unanswered? Our culture is increasingly obsessed with having all information available, all the time. We want what we want as soon as we want it. Even the language is getting more entitled and insistent and irritable. We have “on-demand movies,’’ “instant messaging,’’ “one-click ordering.’’ Now, damn it! But as the gap shrinks between wondering and knowing, between desiring and possessing, we may be losing something important: the tantalizing ache of the unattainable. To want something and not be able to get it sounds, on the surface, like deprivation. But wanting can actually be preferable to getting. -

General Meeting 12/17/13 1

General Meeting 12/17/13 SUFFOLK COUNTY LEGISLATURE GENERAL MEETING SIXTEENTH DAY December 17, 2013 Verbatim Transcript MEETING HELD AT THE WILLIAM H. ROGERS LEGISLATURE BUILDING IN THE ROSE Y. CARACAPPA LEGISLATIVE AUDITORIUM 725 VETERANS MEMORIAL HIGHWAY SMITHTOWN, NEW YORK Minutes Taken By Alison Mahoney & Lucia Braaten - Court Reporters 1 General Meeting 12/17/13 (The following was transcribed by Kim Castiglione, Legislative Secretary) P.O. HORSLEY: Will all Legislators please come to the horseshoe? We're about to start the meeting. Mr. Clerk, would you please call the roll? MR. LAUBE: Good morning, Mr. Presiding Officer. D.P.O. HORSLEY: Good morning. (Roll Called by Tim Laube - Clerk of the Legislature) LEG. KRUPSKI: Here. LEG. SCHNEIDERMAN: Here. LEG. BROWNING: (Not Present) LEG. MURATORE: (Not Present) LEG. HAHN: (Not Present) LEG. ANKER: Here. LEG. CALARCO: (Not Present) LEG. MONTANO: (Not Present) LEG. CILMI: Here. LEG. BARRAGA: Here. LEG. KENNEDY: Here. LEG. NOWICK: Here. LEG. GREGORY: Here. LEG. STERN: 2 General Meeting 12/17/13 Here. LEG. D'AMARO: Here. LEG. SPENCER: (Not Present) P.O. HORSLEY: Here. MR. LAUBE: Eleven. LEG. BROWNING: Tim, sorry. LEG. MURATORE: Tim. MR. LAUBE: Thirteen. P.O. HORSLEY: I suspect that some of our members are not here because of the snow and traffic is pretty rough in a lot of locations throughout the Island. There's rubbernecking, there's accidents. Ms. Nowick is giving me a traffic report here. She says it's miserable out there. (*Laughter*) So everyone be careful today. When you leave here, be careful. I wanted to also note for the record that Legislator Montano has an excused absence for the morning session and he'll be here later. -

November 2020 3 Auxiliary Emergency Fund Linda Knoblach-Harkness

THIS MONTH’S FEATURED 3 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 4 AUXILIARY EMERGENCY FUND Ann King-Smith Linda Knoblach-Harkness 4 DISTRICT 6 5 DISTRICT 14 Mary LaNoce Stacy Cusano 6 UNIT 72 Joanne Scales-Borowy Also Including... NEC 7 OUR EMBLEM 8 CHAPLAIN 9 MEMBERSHIP PROTOCOL 10 JUNIORS 11 LEADERSHIP 12 VETERANS AFFAIRS & REHABILITATION 13 Mission Statement PARLIAMENTARIAN 14 POPPIES 16 FLORIDA ALA HAPPENINGS 18 In the spirit of Service, Not Self, the mission of the ACTIVITIES 26 American Legion Auxiliary is to support The American MEMBERSHIP REPORTS 28 Legion and to honor the sacrifi ce of those who serve by enhancing the lives of our veterans, military, and their families, both at home and abroad. For God and Country, we advocate for veterans, educate our citizens, mentor youth, and promote patriotism, good citizenship, peace and security. Vision Statement The vision of The American Legion Auxiliary is to support The American Legion while becoming the premier Want to submit an article and/or service organization and foundation of every community photos to MAIL CALL? providing support for our veterans, our military, and their families by shaping a positive future in an atmosphere of fellowship, patriotism, peace and security. alafl .org/submit secretary@alafl .org THETH AMERICANAMERA ICANN LEGIONLEGL ION AUXILIARY,AUXILIARY, DEPARTMENTDEPARTMENT OF FLORIDAFLORIDARID PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE ANN KING-SMITH November is always a busy month for our Florida great inspiration and Auxiliary members, as we have Veteran’s Day and beginning for 2021. Thanksgiving both in the same month. Due to the rising numbers of Covid-19 in Florida, I know Please remember to submit your submissions we will be thinking out of the box and celebrating to Department Secretary Patty MacDonald by both special days in ways that may be quite December 15th. -

The Chalice Whitsunday; Stump the Vicar; Mother’S Day with M a Y 2 0 2 0 Gratitude

ST. FRANCIS’ EPISCOP A L C H U R C H IN THIS ISSUE E U R E K A , M O Page 1: Mom was a good mom Page 2: From the Arch- deacon’s Desk Page 3: Pentecost/ The Chalice Whitsunday; Stump the Vicar; Mother’s Day with M A Y 2 0 2 0 gratitude Page 4: Masks for St. Luke’s; From the Bishop’s Warden Page 5: Friends of St. Mom was a good mom! Francis; Garden Talk: Flowering Dogwoods by Father Al Jewson the second Sunday in May member most about her was Page 6: Eureka Food My oldest sister, Jean Marie mothers everywhere gathered her goodness and compas- Pantry; Masks thank you; died on September 22, 2019, at churches, brunches, and sion. She was a warm, loving Prayer requests and was buried from St. Fran- other activities to be honored person who always took to Page 7: Bible Study; Book cis’ Church. Jean was develop- for 365 days of loving service time to find the beauty in Group; Mother’s Day mentally disabled and I was and parenting. This year, 2020 Prayer each person she met. It was her guardian from 1990 until our remembrance will be very from Lillian that I inherited the Page 8: Calendar her death; she lived in a facili- different. I’ll come back to gift of greeting strangers, talk- ty that cared such individuals. this. ing with clerks by name at the When I arrived for a visit Jean check-out, greeting service would excitedly shout, “My personnel before I ask the broder, Afid (Alfred)!”, and location of an item, etc. -

Welcome, Everyone, and Thank You So Much for Joining Us for the Indigenous Wisdom for the Earth Series

Welcome, everyone, and thank you so much for joining us for the Indigenous Wisdom for the Earth series. This series is a place for indigenous people to share their wisdom, their cultural heritage, their beliefs, and the challenges that they face. It is also for groups who work to help indigenous people to bring a voice to their needs and offer ways that you can get involved. The purpose of the series is to open our hearts and minds to cultures who have treasured our planet and could share with us insights that we can use to become more connected with nature and each other. We hope that you will be inspired, informed and intrigued. This month our guest is Madi Sato of Praising Earth. Madi is a singer, community leader, and ceremonialist of Japanese Ainu and Celtic roots. She is devoted to raising women’s voices for the benefit of our Earth Mother. Madi and her husband, poet Timothy P. McLaughlin, are the co-founders of PRAISING EARTH, an organization devoted to rewilding the human heart through the traditions of song, story, dance and ritual to enliven all people’s essential belonging to Earth. Praising Earth with Madi Sato ~ Cover © TreeSisters 2020 Terra: Welcome everyone. Thank you so much for joining us the Indigenous Wisdom for the Earth series. We have a very special guest today. Her name is Madi Sato. Madi Sato is a singer, community leader and ceremonialist of Japanese Ainu and Celtic roots. She's devoted to raising women's voices for the benefit of our Earth Mother and her Sacred Waters. -

Celtic Evensong St. George's Episcopal Church

Celtic Evensong St. George’s Episcopal Church August 30, 2020 - The Thirteenth Sunday After Pentecost 5:30 pm - Online Worship You are welcome at St. George’s Church: Regardless of race, nationality, sexual orientation, gender expression, or tradition. The Thirteenth Sunday After Pentecost August 30, 2020 Welcome to our online service! During the prelude, we invite you to prepare for worship by observing silence or taking time for private prayer. We are glad you are here! Welcome Prelude Silence Opening Reading: From A Grateful Heart Thomas Merton The reality that is present to us and in us: call it Being...Silence. And the simple fact that by being attentive, by learning to listen (or recovering the natural capacity to listen) we can find ourselves engulfed in such happiness that it cannot be explained: the happiness of being at one with everything in that hidden ground of Love for which there can be no explanations… May we all grow in grace and peace., and not neglect the silence that is printed in the centre of our being. It will not fail us. Prayer for the Evening Officiant: In Luke’s gospel, Jesus called together the disciples and a great mul- titude to a level place. There he touched, healed, and taught. There he spoke, “Blessed are…” There he named the blessed—the saints of the faith. All: O God, call us together as you did those so long ago to discover your bless- ed people. This evening, Christ gather us. Officiant: Let us remember, confess, celebrate, and embody the blessed saints of God. -

Craig Farkash

How Blue Can You Get? Urban Mythmaking and the Blues in Edmonton, Alberta by Craig Farkash A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology University of Alberta © Craig Farkash, 2019 Abstract The blues is a genre of music that is rich in storytelling. Growing out of an oral tradition that has spanned generations, its influence on popular music today is undeniable. Many will have some vague recollection of some of these stories—whether related to blues figures, cities, regions, or to moments in time these are stories shared by the entire blues community, and through them, people have become familiar with the mythical importance of places such as Chicago or the Mississippi Delta to blues music. But how does a system of myth-making work in regions that do not have the luxury of being at a blues crossroads? Using the Edmonton blues scene as a case study, this thesis examines some of the stories told by people who have long called Edmonton their home and who have contributed to the mythologization of the local blues scene and turned it into an unlikely home for the blues. By employing qualitative research methodologies, such as participant observation and in-depth interviews, this study aims to understand the role that mythmaking has played in strengthening the Edmonton blues scene. To demonstrate this, the thesis first introduces the history of the Edmonton blues scene and, more generally, the city itself. It then looks at how myth has been written about by other anthropologists and popular music researchers.