1Euro= 2,20371 Gulden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geschiedenis En Achtergronden Van De Sport • #84 • Februari 2018 Moderne Schaatsgeschiedenis Bosatlas Nederlandse Voetbal Cu

de Geschiedenis en achtergronden van de sport • #84 • februari 2018 SPORTWERELD Moderne schaatsgeschiedenis Bosatlas Nederlandse voetbal Curling en kunstrijden Van de redactie In dit nummer Natuurlijk zijn alle bijdragen aan de SPORTWERELD van harte Een aparte derby der Lage Landen 4 welkom, maar we verklappen geen geheim als we als redactie Stijn Knuts melden dat we ook heel graag artikelen plaatsen over sport Geheim Spel 9 dat er zelf twee. Stijn Knuts schrijft over de eerste voetbalin- Jurryt van de Vooren terlandsen sportbeoefening tussen Nederlandse bij de zuiderburen. en Belgische In dezejournalistenteams aflevering zijn vlak voor de Eerste Wereldoorlog en Ryan Stevens over En de moderne schaatsgeschiedenis begon Robert van Zeebroeck, de eerste Belgische medaillewinnaar in 1893… in Amsterdam! 11 op de Olympische Winterspelen in St. Moritz 1928, waar hij Marnix Koolhaas brons haalde bij het kunstrijden. Ryan is zelf een Canadees Ze moeten wel 15 over zijn sport. Check vooral: http://skateguard1.blogspot. Jan Luitzen & Wim Zonneveld nl/oud-kunstrijder, die nu een ongelooflijk mooi blog bijhoudt Buitenlanders die mooi en bevlogen schrijven over sport in De curve die de steen maakt 19 de Lage Landen? Zo maar wat voorbeelden. Wie kent niet de Onno Kosters Engelse beschrijving van het Nederlandse ‘totaalvoetbal’ met Cruyff en Michels door David Winner in Briljant Oranje, het Het Nederlandse voetbal in kaart gebracht 20 genie van het Nederlandse voetbal (Engels 2000, Nederlands Wilfred van Buuren 2006). De in Den Haag geboren publicist-oriëntalist Ian Buruma – oud-cricketer bij HCC en in 2017 hoofdredacteur Kunstrijder met brons in Sankt Moritz 22 geworden van de prestigieuze New York Review of Books – Ryan Stevens bracht in 1991 Anton Geesink prachtig onder de aandacht van het internationale publiek met de beschrijving van het Eduard van Amstel: eervol ontslagen U.D.’er 26 effect van Geesinks olympische overwinning in Tokyo 1964 Nico van Horn op de, na de Wereldoorlog herstellende, Japanse volkspysche. -

We Mogen Weer!!

Clubkrant V.V. De Meern—Jaargang 52, seizoen 2020-2021, nummer 1 WE MOGEN WEER!! (...EEN SOORT VAN.) Technisch manager Sjaak van den Zaterdag 1 trainer Helder: Alain Hijman: ‘Ik vind De Meern ‘We zijn nu nog nog teveel 2 te wisselvallig. verschillende verenigingen. Een Maar het werk- vereniging van klimaat is selectieteams en positief. Een een vereniging van belangrijke niet-selectieteams.’ voorwaarde voor succes.’ HEEL REDACTIONEEL: IEDEREEN WORDT DE ALLERBESTE Kampioen worden. Europees voetbal halen. In het linkerrijtje komen. De Ook een minder mooie trend wordt, doelstellingen van trainers en clubbestuurders in de Eredivisie zijn immer óók bij onze club, pijnlijk voel- en hoog gegrepen. Ondertussen is promoveren het altijd terugkerende tover- zichtbaar. Een gebrek aan vrijwilligers woord in de Eerste Divisie. Wel lekker; aan het begin van het seizoen de- én een gebrek aan plichtsbesef. We le- gradeert niemand en staat iedereen aan de vooravond van de absolute ven in een periode met veel meer regel- doorbraak. Bestaat de sportwereld uit louter winnaars. tjes en ongemakken dan in het recente verleden. Toch wordt van de club ge- Dromen van een topseizoen met persoonlijke triomftochten is niet alleen vraagd die regels toe te passen. Stui- voorbehouden aan hen die van voetbal hun beroep hebben gemaakt. Nee, tend om, in het slotwoord van de voor- zeker ook bij jongens en meisjes die hopen dat ooit voor elkaar te krijgen, is torenhoge ambitie niet vreemd. Dat geldt ook bij onze club. Ook hier zitter, te lezen dat met enige regelmaat wordt er lustig op los gedroomd van een loopbaan in het betaalde voet- die regels, door enkele leden van de bal. -

Giovanni Van Bronckhorst D-Jeugd Edwin Krohne

DeVoetba lTrainer 30 e JAARGANG | JUNI 2013 | www.devoetbaltrainer.nl nummer nummer 194 Trainerscongres 2013 Mini-special Training, discussie en Cursus Coach Betaald Voetbal Awards Remy Reijnierse Leercoach 25 jaar na EK 1988 Succesfactoren KNVB-katern Iedereen heeft Voetbaltalent GEEN TALENT MAG VERLOREN GAAN nummer nummer 7 Danny Volkers Relatiegerichte trainer Peter Wesselink Bewust handelen Coachen van emoties Wat kun je doen als trainer? Spelregels Kennis voorkomt frustratie Goede initiatieven Clubs maken er werk van Robur et Velocitas verhoogt participatie in club Column Geen excuus Thema-nummer Sportiviteit en respect trainers.voetbal.nl De Voetbaltrainer 194 2013 55_coverknvb-katern.indd 55 21-05-13 16:05 De JeugdVoetbalTrainer De JeugdVoetba lTrainer 3e JAARGANG | JUNI 2013 | www.devoetbaltrainer.nl nummer nummer 17 Normaal gedrag René Koster Zelfregulatie Onderzoek Talentontwikkeling Rijpen van hersenen Vrijheid geven Balanceren Thema: Aanvallen op helft tegenstander A-jeugd John Dooijewaard B-jeugd Paul Bremer C-jeugd René Kepser Giovanni van Bronckhorst D-jeugd Edwin Krohne 31_JVT-cover.indd 31 22-05-13 08:20 ‘Ideaal leerjaar’ 01_cover.indd 1 22-05-13 08:23 Superactie van DeVoetba lTrainer Word ook abonnee & profi teer mee! DeVoetba lTrainer 30 e JAARGANG | APRIL 2013 | www.devoetbaltrainer.nl nummer nummer 193 Voetbaltrainer Omgang met media De sliding Vooroordelen Aad de Mos Zoekt creatieve trainers Presteren onder druk Mentaal trainbaar KNVB-katern Iedereen heeft Voetbaltalent GEEN TALENT MAG VERLOREN GAAN nummer nummer -

Clubs Without Resilience Summary of the NBA Open Letter for Professional Football Organisations

Clubs without resilience Summary of the NBA open letter for professional football organisations May 2019 Royal Netherlands Institute of Chartered Accountants The NBA’s membership comprises a broad, diverse occupational group of over 21,000 professionals working in public accountancy practice, at government agencies, as internal accountants or in organisational manage- ment. Integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality and professional behaviour are fundamental principles for every accountant. The NBA assists accountants to fulfil their crucial role in society, now and in the future. Royal Netherlands Institute of Chartered Accountants 2 Introduction Football and professional football organisations (hereinafter: clubs) are always in the public eye. Even though the Professional Football sector’s share of gross domestic product only amounts to half a percent, it remains at the forefront of society from a social perspective. The Netherlands has a relatively large league for men’s professio- nal football. 34 clubs - and a total of 38 teams - take part in the Eredivisie and the Eerste Divisie (division one and division two). From a business economics point of view, the sector is diverse and features clubs ranging from listed companies to typical SME’s. Clubs are financially vulnerable organisations, partly because they are under pressure to achieve sporting success. For several years, many clubs have been showing negative operating results before transfer revenues are taken into account, with such revenues fluctuating each year. This means net results can vary greatly, leading to very little or even negative equity capital. In many cases, clubs have zero financial resilience. At the end of the 2017-18 season, this was the case for a quarter of all Eredivisie clubs and two thirds of all clubs in the Eerste Divisie. -

1. Verslag Van Het Bestuur

1. Verslag van het bestuur Het afgelopen seizoen was succesvol voor FC Volendam. In het eerste jaar na de aanstelling van een vrijwel compleet nieuwe technische staf stond de club begin maart op de derde plaats in de Keuken Kampioen Divisie. Daarvoor was al beslag gelegd op de tweede periode, waardoor deelname aan de Play Offs gegarandeerd was. Echter, het Coronavirus gooide in maart roet in het eten, waardoor het betaald voetbal van overheidswege noodgedwongen werd stop gezet. Hierdoor werd de competitie niet afgemaakt en kon FC Volendam geen verdere gooi doen naar promotie naar de Eredivisie. In het KNVB Beker toernooi werd FC Volendam vroegtijdig uitgeschakeld door Sparta Rotterdam. Organisatorisch gezien was dit het eerste seizoen van het nieuwe bestuur. In de laatste twee maanden van het seizoen vond er in het bestuur een wijziging plaats. Richard de Weijze werd per 1 mei 2020 benoemd als nieuwe zakelijk directeur van FC Volendam. Daarom verviel zijn bestuursfunctie. De portefeuille werd inhoudelijk onderdeel van de dagelijkse praktijk en derhalve geen bestuursfunctie meer. Financieel Het seizoen werd financieel afgesloten met een positief nettoresultaat van EUR 1.713.269. Het goede presteren van het eerste elftal was daar mede debet aan. Met name het FC Volendam Participatiefonds zorgde voor een forse plus in het resultaat. FC Volendam eindigde het seizoen met een eigen vermogen van EUR 1.506.894,- positief. Op het balanstotaal leidt tot een solvabiliteitsratio van 34,17%. Met in achtneming van de achtergestelde leningen komt FC Volendam op een weerstandsvermogen van 52,4%. De liquiditeitspositie is per 30 juni 2020 EUR 2.484.208. -

Conceptprogramma Keuken Kampioen Divisie

CONCEPTPROGRAMMA KEUKEN KAMPIOEN DIVISIE SEIZOEN 2020/’21 1 Ronde Datum Thuis Uit Tijd 1 vrijdag 28 augustus 2020 Jong FC Utrecht FC Eindhoven 18:45 1 vrijdag 28 augustus 2020 SC Cambuur N.E.C. 21:00 1 zaterdag 29 augustus 2020 Jong PSV Excelsior 16:30 1 zaterdag 29 augustus 2020 TOP Oss Helmond Sport 18:45 1 zaterdag 29 augustus 2020 NAC Jong AZ 21:00 1 zondag 30 augustus 2020 Telstar FC Volendam 12:15 1 zondag 30 augustus 2020 Jong Ajax Roda JC 14:30 1 zondag 30 augustus 2020 FC Dordrecht Go Ahead Eagles 16:45 1 zondag 30 augustus 2020 Almere City FC MVV 20:00 1 maandag 31 augustus 2020 De Graafschap FC Den Bosch 20:00 Int vrijdag 4 september 2020 Jong Wit Rusland Jong Oranje Int vrijdag 4 september 2020 Nederland Polen 20:45 Int vrijdag 4 september 2020 Nederland O19 Zwitserland O19 Int maandag 7 september 2020 Nederland Italië 20:45 Int dinsdag 8 september 2020 Jong Oranje Jong Noorwegen Int dinsdag 8 september 2020 Tsjechië O19 Nederland O19 2 zaterdag 5 september 2020 FC Eindhoven Telstar 16:30 2 zaterdag 5 september 2020 MVV SC Cambuur 18:45 2 zaterdag 5 september 2020 Roda JC TOP Oss 21:00 2 zondag 6 september 2020 Excelsior Almere City FC 12:15 2 zondag 6 september 2020 Go Ahead Eagles De Graafschap 14:30 2 zondag 6 september 2020 FC Den Bosch FC Dordrecht 16:45 2 zondag 6 september 2020 Helmond Sport NAC 20:00 2 Ronde Datum Thuis Uit Tijd 3 vrijdag 11 september 2020 Jong AZ Jong PSV 18:45 3 vrijdag 11 september 2020 FC Volendam Jong FC Utrecht 18:45 3 vrijdag 11 september 2020 FC Dordrecht Excelsior 18:45 3 vrijdag 11 september 2020 N.E.C. -

PSV Eindhoven and Utrecht (All Eredivisie)

TT0809-98 TT No.98: Chris Freer - 3 Day Dutch Hopping Tour (21 - 23 November 2008): feat. games at FC Volendam; PSV Eindhoven and Utrecht (all Eredivisie). Just got back from our annual 3-day, 3-match tour of the Netherlands and wanted to pass on a few bits of (hopefully) useful info to fellow Euro-hoppers. Travel round the country is easy by trains, which are invariably on time. If there's two of you, share a one-day rail ticket which costs 35 euros and allows unlimited travel throughout the country, in first class sections of the train. These are available on Saturdays and Sundays, although not near Christmas. MATCH 1 - Friday 21 November 2008; FC Volendam v Roda JC (Eredivisie); 3-1; FGIF Rating: 4*. We based ourselves in Amsterdam for both nights this year (the attractions of In De Wildeman too great to miss) and the Friday night game at Volendam was quite handy. This club is one of the up and down teams in the Eredivisie and must be used to playing on Fridays (the preferred day for the Dutch leagues second-tier). Turning left outside Amsterdam Centraal, go to the bus stands and look for a 118. Other bus numbers also go there at different times. The online 9292ov.nl website has timetables. This'll whisk you in just half an hour or so straight to the ground. According to a fan-site I contacted, FC Volendam have introduced club cards this season, but we got round that by contacting the club by e-mail. -

Programma Betaald Voetbal Seizoen 2014/'15 Eredivisie

PROGRAMMA BETAALD VOETBAL SEIZOEN 2014/'15 EREDIVISIE / JUPILER LEAGUE vr EL donderdag 17 + 24 juli 2014 FC Groningen vrijdag 18 juli 2014 loting Q3 CL + EL vr CL dins. 29 / woensdag 30 juli 2014 Feyenoord vr EL donderdag 31 juli 2014 PSV / FC Groningen JCS zondag 3 augustus 2014 PEC Zwolle Ajax 18:00 vr CL din. 5 / woe. 6 augustus 2014 Feyenoord vr EL donderdag 7 augustus 2014 PSV / FC Groningen vrijdag 8 augustus 2014 loting play-offs CL + EL 1 vrijdag 8 augustus 2014 PEC Zwolle FC Utrecht 20:00 1 vrijdag 8 augustus 2014 Roda JC RKC Waalwijk 20:00 1 zaterdag 9 augustus 2014 sc Heerenveen FC Dordrecht 18:30 1 vrijdag 8 augustus 2014 VVV-Venlo Jong FC Twente 20:00 1 zaterdag 9 augustus 2014 SC Cambuur FC Twente 19:45 1 vrijdag 8 augustus 2014 FC Oss FC Volendam 20:00 1 zaterdag 9 augustus 2014 NAC Breda Excelsior 19:45 1 vrijdag 8 augustus 2014 Almere City FC MVV 20:00 1 zaterdag 9 augustus 2014 Heracles Almelo AZ 20:45 1 vrijdag 8 augustus 2014 Helmond Sport Fortuna Sittard 20:00 1 zondag 10 augustus 2014 ADO Den Haag Feyenoord 12:30 1 vrijdag 8 augustus 2014 FC Emmen De Graafschap 20:00 1 zondag 10 augustus 2014 Go Ahead Eagles FC Groningen 14:30 1 zaterdag 9 augustus 2014 Jong PSV Achilles'29 16:30 1 zondag 10 augustus 2014 Ajax Vitesse 14:30 1 zondag 10 augustus 2014 Sparta Rotterdam FC Den Bosch 14:30 1 zondag 10 augustus 2014 Willem II PSV 16:45 1 zondag 10 augustus 2014 N.E.C. -

Eerste Besluit NAC Breda 0,31 MB

Organisatieonderdeel Korpsstaf ..Wob-coördinatiedesk.................................. p LITIE Behandeld door : ••••••••••••••••••.... , Functie Jurist Bezoekadres Nieuwe Uitleg 1 2514 BP Den Haag Telefoon 0900-8844 / 088-1699047 E-mail [email protected] Ons kenmerk KNP16000468 Uw kenmerk Retouradres: Postbus 17107, 2502 CC Den Haag Datum BIJlage(n) 1 (51 pagina's A-4) Per aangetekende post . Pagina 1/2 VERZONDEN 2 8 JUNI 2016 Onderwerp Besluit op Web-verzoeken ... - - - - - - - - 1 Geachte heer ! : Op 22 maart 2016 werd uw verzoek op grond van de Wet openbaarheid van bestuur (hierna: Wob) van 18 maart 2016 ontvangen bij de eenheid Noord-Holland. De goede ontvangst van uw Wob-verzoek werd schriftelijk bevestigd (kenmerk: 16.03453) en de termijn van het nemen van een besluit werd met toepassing van artikel 6, lid 2 van de Wob met vier weken verdaagd. U vraagt om informatie over -kort samengevat- de voetbalwedstrijd FC Volendam• NAC Breda gehouden op 15 januari 2016. 1: Inleiding: Vervolgens werd geconstateerd dat bij meerdere eenheden van de politie soortgelijke Wob-verzoeken van gemeenten ter afhandeling zijn ontvangen. Die Wob-verzoeken heeft de voorzitter (wonende te Etten-Leur) van de Stichting Clul!>raad NAC, het vertegenwoordigend supportersorgaan van alle NAC supporters, bij alle gemeenten met een Jupiler League club ingediend. Nu er sprake is van meer soortgelijke Wob• verzoeken met een landelijk karakter wordt de afhandeling gedaan door de korpsstaf te Den Haag en werd u bij brief d.d. 20 april 2016 daarvan in kennis gesteld. Daarnaast werd aan u verzocht om kenbaar te maken hoeveel soortgelijke Wob• verzoeken u nog heeft ingediend. Bij email van 22 april 2016 maakte de voorzitter van de Stichting Clubraad NAC bekend, dat hij bij alle gemeenten met een Jupiler League club een Wob-verzoek te hebben ingediend. -

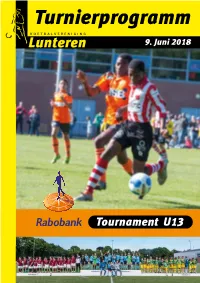

Turnierprogramm

Turnierprogramm . Juni 2018 Vorwort “Ich hätte lieber eine gute statt gute - spieler Rabobank Gelderse Vallei verbürgt lokale Aktivitäten im Bereich Sport, Kultur und Gesellscha . Vielleicht o en einen Schuss für Ziel aber die Jugend ist die Zukun , so wir uns natürlich mit diesem “Rabobank Turnier U freuen”! Den Sport auf dem Feld entlang der Linie und natürlich mit all den freiwilligen zusammenbringen. Wir freuen uns auch, wer so viel Energie in die Organisation dieses Turniers. Denn nicht nur Sie gewinnen, gewinnen tun Sie untereinander. Jos Goor, Manager MKB Rabobank Gelderse Vallei Vorwort Auskün e • Das ”. Rabobank Tournament U” wird vom Fußballverein Lunteren organisiert und ndet am Samstag den . Juni auf dem “Sport- park De Wormshoef” in Lunteren statt. • Das Turnier beginnt um : Uhr, die Preisverleihung ist für : Uhr angesetzt. • Alle Spieler bekommen ein Mittagessen im Vereinsheim des Damm- vereins “D.E.S” (hinter der Tribüne). • Den Betreuer der teilnehmenden Vereine wird ein Mittagessen ange- boten im “Hotel Eethuys De Wormshoef”. Nähere Auskün e hierüber bekommen Sie bei Anmeldung von der Turnierleitung. • Den ganzen Tag gibt es Erste Hilfe und Versorgung auf dem Sportpark. • Die Betreuer werden gebeten die Wertgegenstände der Spieler einzu- sammeln und sicher zu verwahren. • Bitte lesen Sie die Turniersatzung! JBTech Veenendaal B.V. Lunet 16 | Postbus 951 3900 AZ Veenendaal Doordacht T 0318-506134 en duurzaam F 0318-514556 › elektrotechniek › data- en telecommunicatie › beveiliging www.jbtech.nl › energiebesparing Willkommen . Rabobank Tournament U Lunteren, Juni Liebe Fußballfreunde, - vor Jahren - wurde das erste D-Jugend-Tunier des Fußballvereins Lunteren ausgetragen. Die Idee war damals, dieses Turnier innerhalb weniger Jahre zu einem der stärksten U-Jugend-Turniere in den Nie- derlanden zu entwickeln. -

De AFC Vriendelijke Bedrijven 2014-2015

AMSTERDAMSCHE FOOTBALL CLUB Opgericht 18 januari 1895 PERSMAP SEIZOEN 2014-2015 EDITIE 32 Deze persmap is mede mogelijk gemaakt door: De AFC Vriendelijke Bedrijven 2014-2015 AFC-AM-bord1.pdf 1 1/15/14 4:46 PM vastgoedmanagement | makelaardij AFC | 1 KAMPIOEN VAN NEDERLAND Sjoerd Jens, aanvoerder seizoen 2013-2014 2 | In gesprek met de voorzitter WISSELING VAN DE WACHT ijdens AFC’s jaarlijkse Algemene Vergadering Vorig seizoen was voor AFC uiterst succesvol: AFC 1, AFC 2 op 26 juni 2014 trad Machiel van der Woude na en de Junioren A1 werden allen Kampioen. Geen gemakkelijk een periode van 24 jaar bestuurslidmaatschap, moment om in te stappen? waarvan de laatste 11 seizoenen als voorzit- ter, terug uit het AFC-bestuur. Machiel van der De prachtige resultaten uit het voorbije seizoen waren natuurlijk Woude werd benoemd tot Erelid van AFC en is geweldig, maar die zijn niet van de een op andere dag tot stand opgevolgd door de 62-jarige AFC-er Adriaan Westerhof. gekomen. De kampioenschappen zijn een gevolg van een beleid dat Bobby Gehring ging voor deze AFC Persmap met de nieuwe lang geleden is ingezet. Sportief succes valt of staat niet direct met voorzitter in gesprek. de positie van de voorzitter of wie die positie bekleedt. AFC 1 speelt al jaren mee op het hoogste amateurniveau; eerst 33 Geachte voorzitter, beste Ad, jij bent de 17e voorzitter in de seizoenen in de Hoofdklasse en nu voor het vijfde seizoen op rij in bijna 120-jarige geschiedenis van AFC. Een grote eer? de Topklasse. Dat krijg je niet zomaar even voor elkaar. -

De Jeugdvoetbaltrainer Staat Het Boek ‘Ellis En Het Verbreinen’ Van Jelle Jolles Centraal

De JeugdVoetba lTrainer 3e JAARGANG | JUNI 2013 | www.devoetbaltrainer.nl nummer nummer 17 Normaal gedrag René Koster Zelfregulatie Onderzoek Talentontwikkeling Rijpen van hersenen Vrijheid geven Balanceren Thema: Aanvallen op helft tegenstander A-jeugd John Dooijewaard B-jeugd Paul Bremer C-jeugd René Kepser D-jeugd Edwin Krohne 31_JVT-cover.indd 31 22-05-13 08:20 De JeugdVoetba lTrainer Tekst: Alex van Vogelpoel Als je aanpak tóch niet blijkt te werken Het creëren van normaal gedrag Afgelopen seizoen beleefde René Koster een bijzonder jaar met de toenmalige B1 van Almere City. Na zeven wedstrijden stonden er pas drie punten op het bord en was het vooral zeer onrustig in zijn spelersgroep. De ploeg bleek niet in staat om goed om te gaan met de onderlinge afspraken. Koster veran- derde de manier van het benaderen, coachen en begeleiden van zijn spelers en dat pakte zeer goed uit. De B1 van Almere City beleefde een aantal jongens zo goed ging spelen dat René Koster was eerder moeizame start van het seizoen ze binnen een jaar de stap naar het al actief als jeugdtrainer 2011/2012 maar wist via de nacom- eerste elftal van Almere City hebben van AZ en Telstar. Zes petitie alsnog te promoveren naar de gemaakt, voor nationale jeugdteams jaar geleden maakte hij eredivisie. Veel spelers profiteerden werden uitgenodigd of zijn verkocht de overstap naar de C1 van het uiteindelijk succesvolle jaar. aan een grotere club. Terwijl er tijdens van Almere City. Een Koster blikt terug op de wijze waarop de eerste zeven wedstrijden niemand seizoen later werd hij te- hij het team aan de praat kreeg.