Antebellum Posthuman Is a Thought-Provoking and Timely Contribution to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Counter-Enthusiasms: the Rationalization of False Prophecy In

COUNTER-ENTHUSIASMS: THE RATIONALIZATION OF FALSE PROPHECY IN EARLY ENLIGHTENMENT ENGLAND By William Cook Miller A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May, 2016 ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the historical problem of false prophecy—or, more generally, the need to distinguish legitimate from illegitimate forms of contact with the divine—as it influences then-innovative and now-pervasive attitudes toward language and knowledge in early enlightenment England. Against the prevalent senses that the history of popular religion can be characterized either in terms of false consciousness or disenchantment, I argue that the vernacular Bible empowered unauthorized subjects (the poor, women, heterodox thinkers) to challenge dominant English culture in the theological vocabulary of the prophet. This power led to a reaction—which I call counter-enthusiasm—which both polemicized popular prophets as “enthusiasts” beyond the reach of reason, and developed new categorical understandings of experience in order to redefine relations of spirit, body, and word so as to avoid the problem of unlicensed spiritual authority. I concentrate on three counter-enthusiasms—as articulated by Henry More, John Locke, and Jonathan Swift—which fundamentally rethink the links between humanity, divinity, and language, in light of--and in the ironically occupied guise of—the figure of the enthusiast. I argue further that the discourse of enthusiasm contributed centrally to the process known as “the rationalization of society,” which involved the distinction of the categories of self, society, and nature. KEYWORDS: prophecy, enthusiasm, rationalization, enlightenment, language theory, religion, mimesis, hermeneutics, materialism, totality, irony, satire, English Civil War, Interregnum, Restoration, Henry More, Cambridge Platonism, John Locke, Jonathan Swift, Jürgen Habermas. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Drastic Measures by Ben Parris Ben Parris - Editor

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Drastic Measures by Ben Parris Ben Parris - Editor. I'm an editor of books, essays and short stories, a personal trainer for authors, and the author of a Kindle bestseller. Overview. ABOUT BEN PARRIS I'm a professional editor with 30+ years of employment and freelance experience. My emphasis is in adventure/ thriller, anthologies, historical fiction, science fiction, and fantasy, but I work with most fiction genres and some non-fiction. I have edited for New York Times Bestselling authors such as George Clayton Johnson and Irving A. Greenfield. I prefer to begin an editing relationship by providing a writing assessment in order to ensure that an author is not paying for services for which they are not ready. Too often I've been asked to polish up scenes that shouldn't even exist because they serve no purpose in the story or have not yet been developed. Doing a line edit or a copy edit in these instances is like putting icing on a cardboard box and trying to replace the box with a cake later. As I like to say, authors can be in the business of fantasy. Editors need to be in the business of honesty. FAVORITE BOOKS I RECOMMEND FOR LEARNING THE CRAFT Story Structure- Worth Dying for by Lee Child (a Jack Reacher novel) Dialogue- The Black Marble by Joseph Wambaugh Characterization- Rain Man by Lenore Fleischer Voice- Elmore Leonard Setting- Ringworld by Larry Niven Pacing- Rendezvous with Rama by Arthur C. Clarke Prose- Rose Madder by Stephen King Plot and Suspense- Lightening by Dean Koontz Complex Descriptions Made Simple- Joseph Kannon Alien Character Development- An Alien Light by Nancy Kress Note: None of the above constitute the ultimate approach to their respective story elements. -

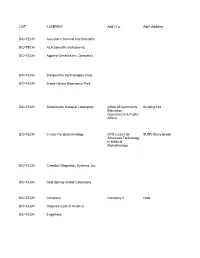

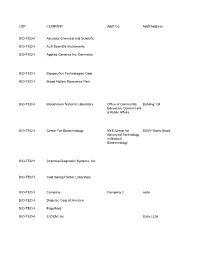

LIST COMPANY Add'l Co. Add'l Address BIO-TECH

LIST COMPANY Add'l Co. Add'l Address BIO-TECH Accurate Chemical and Scientific BIO-TECH ALA Scientific Instruments BIO-TECH Applied Genetics Inc. Dermatics BIO-TECH Biospecifics Technologies Corp. BIO-TECH Broad Hollow Bioscience Park BIO-TECH Brookhaven National Laboratory Office of Community Building 134 Education, Government & Public Affairs BIO-TECH Center For Biotechnology NYS Center for SUNY-Stony Brook Advanced Technology in Medical Biotechnology BIO-TECH Chembio Diagnostic Systems, Inc. BIO-TECH Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory BIO-TECH Company Company 2 code BIO-TECH Diapulse Corp of America BIO-TECH Engelhard BIO-TECH E-Z-EM, Inc. Suite LL26 BIO-TECH Garnett-McKeen Laboratory, Inc. BIO-TECH Hearing Innovations c/o Misonix BIO-TECH Helicon Therapeutics BIO-TECH International BioImmune Systems, Inc. BIO-TECH IRX Therapeutics Suite 9C BIO-TECH Metavac LLC BIO-TECH Nanoprobes Unit 1 BIO-TECH OSI Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Suite 110 BIO-TECH Pall Corporation BIO-TECH Precision Pharma Services, Inc. BIO-TECH Redox Pharmaceutical Corp. BIO-TECH The Feinstein Institute for Medical Boas Marks Research Research Building BIO-TECH United Biomedical, Inc. COLLEGES Abilities, Inc. COLLEGES Access Careers COLLEGES Adelphi University South Ave. COLLEGES Branford Hall Career Institute COLLEGES Briarcliffe College, Patchogue Campus COLLEGES Briarcliffe College, Bethpage Campus COLLEGES Brookhaven Technical Center (BOCES) COLLEGES Career Institute of Health & Technology Suite 519 COLLEGES CLARUS Training Solutions, Inc. Suite 100 E COLLEGES Commercial -

Omega Psi Phi Fraternity 4; Student Senate 2,3,4

LLOYD S. HIGGS Editor-in-Chiet DONALD L. PIERCE Assoc. Editor PUBLISHED BY THE JAMES A. PINDER SENIOR CLASS OF LINCOLN UNIVERSITY Art & Photo Editor LINCOLN UNIVERSITY, PENNSYLVANIA. DONALD R. UKKERD Managing Editor BASIL P. GORDON nineteen hundred Business Manager THE SCHOOL PAGE 7 Pictorial representation of six campus build- ings . Brief history of the school. ADMINISTRATION PAGE 11 6084 (J The President . Dean of the University . Dean of the Seminary . Dean of Men . The Registrar . Faculty . Trustees r« oreword SENIORS PAGE 19 Class Advisor . Class Officers . Indi- vidual Photographs and Comments . Class History . Who's Who . Junior, Sophomore, and Freshmen Classes Leaving this institution which has grown dear to us, we, the class of '53 are confident ACTIVITIES PAGE' 51 that we have spent here tour worthy years, Social and Educational Clubs tour ot the best years of our lives. We have moulded our lives and minds to fit the pattern laid down for us by the great educators of the past. Therefore in seeking other success, we expect to be definite assets to our communities and to our countries. FRATERNITIES PAGE 63 Kappa Alpha Psi . Alpha Phi Alpha . This yearbook mirrors true experience, puts Beta Sigma Tau . Phi Beta Sigma . into print what we have accomplished, and Omega Psi Phi tells of our aspirations. With the help ot the entire campus community, we ot the Lion Statt have sought to produce a yearbook rich in the traditions ot Lincoln University, a prologue to the future. We wish to thank all who have helped to make us what we are, and all who SPORTS PAGE 69 have contributed so graciously to this our Football . -

Solving a Mystery, Living in Otheparts of the World, Imagining the Future, Traveling in Space, and Magic and the Supernatural

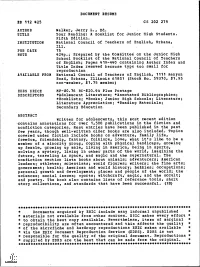

DOCUMENT RESUME BD 112 425 CS 202 279 AUTHOR Walker, Jerry L., Ed. TITLE Your Reading: A Booklist for Junior High Students. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of leachers of English, Urbana, Ill. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 424p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Junior High School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English; Pages 419-440 containing Author Index and Title Index removed because type too small for reproduction AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801 (Stock No. 59370, $1.95 non-member, $1.75 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$20.94 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Annotated Bibliographies; *Booklists; *Books; Junior High Schools; Literature; Literature Appreciation; *Reading Materials; Secondary Education ABSTRACT Written for adolescents, this most recent edition 'contains annotations for over 1,500 publications in the fiction and nonfiction categories. Most entries have been published in the past few years, though well-written older books are also included. Topics covered under fiction include books on adventure, family life, freedom, friendship, fantasy, folklore, love, what it's like to be a member of a minority group, coping with physical handicaps, growing up female, growing up male, living in America, being in sports, solving a mystery, living in otheparts of the world, imagining the future, traveling in space, and magic and the supernatural. The nonfiction section lists books about animals; adventurers; American leaders; athletes; scientists; world figures; writers; the fine arts; government; health; American and world history; hobbies; occupations; personal growth and development; places and people of the world; the sciences; social issues; sports; witchcraft; magic, and the occult; and poetry. -

COLLEGE of ARTS and SOCIAL SCIENCES Research School Of

COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Research School of Humanities and the Arts SCHOOL OF ART & DESIGN ART AND DESIGN HIGHER DEGREE BY RESEARCH DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY DEIRDRE FEENEY VISIBILITIES AND INVISIBILITIES OF WONDER: A PRACTICE-LED EXPLORATION OF OPTICAL IMAGE SYSTEMS EXEGESIS SUBMITTED IN PART FULFILMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF THE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY MARCH 2019 © Deirdre Feeney 2019 All Rights Reserved 1 Declaration of Originality I, Deirdre Feeney hereby declare that the thesis here presented is the outcome of the research project undertaken during my candidacy, that I am the sole author unless otherwise indicated, and that I have fully documented the source of ideas, references, quotations and paraphrases attributable to other authors. 01 March 2019. 2 Visibilities and Invisibilities of Wonder: A Practice-Led Exploration of Optical Image Systems 3 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank all who contributed to my project. I am grateful to my research panel, Professor Helen Ennis, Associate Professor Richard Whiteley, Dr John Debs and Associate Professor Martyn Jolly for providing guidance and feedback throughout my candidature. I would especially like to thank Helen Ennis for her support with my writing and whose interest in my project went beyond her time at the School of Art & Design (SoA&D). I am also particularly grateful to John Debs at the ANU Research School of Physics and Engineering, who opened the door for me to a whole new world of material knowledge. I extend my gratitude to Merryn Gates for her fastidious copy-editing and to the SoA&D graduate team, in particular Dr Charlotte Galloway, Barbara McConchie, Anne Masters and Max Napier for their support. -

The Play in the System : the Art of Parasitical Resistance / Anna Watkins Fisher

THE PL AY IN THE SYSTEM This page intentionally left blank THE PLAY THE ART IN OF PARASITICAL RESISTANCE THE SYSTEM ANNA WATKINS FISHER Duke Univer sit y Pr ess Durham and London 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Aimee C. Harrison Typeset in Minion Pro and Vectora by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Fisher, Anna Watkins, author. Title: The play in the system : the art of parasitical resistance / Anna Watkins Fisher. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: l cc n 2019054723 (print) | l cc n 2019054724 (ebook) isbn 9781478008842 (hardcover) isbn 9781478009702 (paperback) isbn 9781478012320 (ebook) Subjects: l csh: Arts—Political aspects—History—21st century. | Arts and society—History—21st century. | Artists—Political activity. | Feminism and the arts. | Feminism in art. | Artists and community. | Politics and culture. | Arts, Modern—21st century. Classification: l cc n x180.p64 f 57 2020 (print) | l c c nx180.p64 (ebook) | dd c 700.1/03—dc23 l c record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054723 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054724 isbn 9781478091660 (ebook/other) Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the Office for Research (umor ) and the College of Literature, Science and the Arts (l sa ) at the University of Michigan, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries. -

LIST COMPANY Add'l Co. Add'l Address BIO-TECH Accurate

LIST COMPANY Add'l Co. Add'l Address BIO-TECH Accurate Chemical and Scientific BIO-TECH ALA Scientific Instruments BIO-TECH Applied Genetics Inc. Dermatics BIO-TECH Biospecifics Technologies Corp. BIO-TECH Broad Hollow Bioscience Park BIO-TECH Brookhaven National Laboratory Office of Community Building 134 Education, Government & Public Affairs BIO-TECH Center For Biotechnology NYS Center for SUNY-Stony Brook Advanced Technology in Medical Biotechnology BIO-TECH Chembio Diagnostic Systems, Inc. BIO-TECH Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory BIO-TECH Company Company 2 code BIO-TECH Diapulse Corp of America BIO-TECH Engelhard BIO-TECH E-Z-EM, Inc. Suite LL26 BIO-TECH Garnett-McKeen Laboratory, Inc. BIO-TECH Hearing Innovations c/o Misonix BIO-TECH Helicon Therapeutics BIO-TECH International BioImmune Systems, Inc. BIO-TECH IRX Therapeutics Suite 9C BIO-TECH Metavac LLC BIO-TECH Nanoprobes Unit 1 BIO-TECH OSI Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Suite 110 BIO-TECH Pall Corporation BIO-TECH Precision Pharma Services, Inc. BIO-TECH Redox Pharmaceutical Corp. BIO-TECH The Feinstein Institute for Medical Boas Marks Research Research Building BIO-TECH United Biomedical, Inc. COLLEGES Abilities, Inc. COLLEGES Access Careers COLLEGES Adelphi University South Ave. COLLEGES Branford Hall Career Institute COLLEGES Briarcliffe College, Patchogue Campus COLLEGES Briarcliffe College, Bethpage Campus COLLEGES Brookhaven Technical Center (BOCES) COLLEGES Career Institute of Health & Technology Suite 519 COLLEGES CLARUS Training Solutions, Inc. Suite 100 E COLLEGES Commercial -

Sariwexi Marketing Videos

sariwexi Marketing Videos: Real People, Real Choices, Michael R. Solomon , 2009, 0136053912, 9780136053910. Statement of Accounts for the Year Ended 31 March 1990 Together with the Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General Thereon, Independent Commission for Police Complaints for Northern Ireland , 1991, 0102199914, 9780102199918. My Diary, New Holland , 2010, 1741109892, 9781741109894. A must-have for any little ballerina, this hard cover lockable diary with a beautifully illustrated cover - a place to write down her dreams and wishes. Comes with heart shaped padlock and keys. Bridget Jones's Guide to Life, Helen Fielding , 2001, 0142000213, 9780142000212. She'll help you get your life in order. She'll help you get your home in order. Or she'll at least help you place a take-out order. In this elegant and practical handbook, Bridget Jones - the intrepid thirty-something Singleton on a permanent but doomed quest for self- improvement - offers a road to perfection in the fields of cooking, streamlined inner thighs and poise, spiritual and romantic nirvana, accounting, an understanding of Feng Shui, what men think they might feel they want, and creating a fragrant home. She's read the self-help books - all of them. And committed most of them to memory. Now Bridget breaks out on her own to give readers the benefit - benefit? - of her rich experience. Module N Bld-a-kitadvantage, Harcourt Brace Publishing , 1998, 0153096616, 9780153096617. The Bones of Garbo: A Collection of Short Stories, Trudy L. Lewis , 2003, 0814251099, 9780814251096. Australian Arts Guide, Roslyn Kean , 1981, 0950716030, 9780950716039. Gravure #5, Alex Freund, Lisa Mosko , 2011, 0983191158, 9780983191155.