IDAOO-0000-G210 Women in Mauritania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emea 2012/2013

République Islamique de Mauritanie Honneur – Fraternité – Justice Ministère du Développement Rural Direction des Politiques, de la Coopération, du Suivi et de l’Evaluation (DPCSE) Résultats de la campagne agricole 2012/2013 EMEA 2012/2013 JUILLET 2013 TABLE DE MATIERE Résumé ....................................................................................................................................... 3 AVANT PROPOS ...................................................................................................................... 4 I. Présentation de l’Enquête auprès des Ménages et Exploitants Agricoles (EMEA) ........... 5 1.1 Champ de l’enquête EMEA ............................................................................................. 5 1.2 Méthodologie ................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Périodicité des publications .............................................................................................. 6 II. Programmation de la Campagne agricole .......................................................................... 7 2.1. Les objectifs de mise en valeur par sous secteur ............................................................. 7 2.2 Les Mesures envisagées ................................................................................................... 7 III. Déroulement de la Campagne agricole ........................................................................ 10 3.2. Situation hydrologique ................................................................................................. -

Evaluation and Assessment of Meteorological Drought by Different Methods in Trarza Region, Mauritania

Water Resour Manage (2017) 31:825–845 DOI 10.1007/s11269-016-1510-8 Evaluation and Assessment of Meteorological Drought by Different Methods in Trarza Region, Mauritania Ely Yacoub1 & Gokmen Tayfur1 Received: 6 June 2016 /Accepted: 20 September 2016 / Published online: 10 October 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2016 Abstract Drought Indexes (DIs) are commonly used for assessing the effect of drought such as the duration and severity. In this study, long term precipitation records (monthly recorded for 44 years) in three stations (Boutilimit (station 1), Nouakchott (station 2), and Rosso (station 3)) are employed to investigate the drought characteristics in Trarza region in Mauritania. Six DI methods, namely normal Standardized Precipitation Index (normal-SPI), log normal Standardized Precipitation Index (log-SPI), Standardized Precipitation Index using Gamma distribution (Gamma-SPI), Percent of Normal (PN), the China-Z index (CZI), and Deciles are used for this purpose. The DI methods are based on 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12 month time periods. The results showed that DIs produce almost the same results for the Trarza region. The droughts are detected in the seventies and eighties more than the 1990s. Twelve drought years might be experienced in station 2 and six in stations 1 and 3 in every 44 years, according to reoccurrence probability of the gamma-SPI and log-SPI results. Stations 1 and 3 might experience fewer drought years than station 2, which is located right on the coast. In station 1, which is located inland, when the annual rainfall is less than 123 mm, it is likely that severe drought would occur. -

A Study of the Association of Parental Consanguinity with Birth Defects and Neonatal Medical Problems in Babylon Province

Journal of University of Babylon, Pure and Applied Sciences, Vol.(26), No.(6): 2018 A Study of the Association of Parental Consanguinity with Birth Defects and Neonatal Medical Problems in Babylon Province Sijal Fadhil Farhood Al-Joborae Department of Community Medicine Babylon College of Medicine, University of Babylon [email protected] Ehab Raad Abbas al-Sadik Babylon health directorate [email protected] Ameer Kadhum Hussein Al-Humairi. Department of Community Medicine Babylon College of Medicine, University of Babylon [email protected] Hadeel Fadhil Farhood Al-Joborae Department of Community Medicine Babylon College of Medicine, University of Babylon [email protected] Ashraf Mohammed Ali Hussein Department of Community Medicine Babylon College of Medicine, University of Babylon Abstract A cross-sectional study of 138 married couples and their offspring was done in Babylon Province from the period between the first of February till the end of April 201 6 . The parents; who were either consanguine or no consanguine, came from mixed urban and rural backgrounds. Socio -demographic and obstetric data were recorded. Neonatal data were extracted from the medical records of the labor and neonatal care wards. The incidence of congenital and birth defects was significantly higher for those born to consanguine parents especially for first cousin couples. The incidence of congenital abnormalities in newborns of all non-consanguineous parents was 7.1% as compared to 23.2 % for newborns of all consanguineous group. In addition prematurity, history of previous prenatal mortality, and low birth weight were more common in the consanguineous group. Keywords: Consanguinity, birth defects, neonatal medical problems, Babylon province 1. -

Wvi Mauritania

MAURITANIA ZRB 510 – TVZ Nouakchott – BP 335 Tel : +222 45 25 3055 Fax : +222 45 25 118 www.wvi.org/mauritania PHOTOS : Bruno Col, Coumba Betty Diallo, Ibrahima Diallo, Moussa Kante, Delphine Rouiller. GRAPHIC DESIGN : Sophie Mann www.facebook.com/WorldVisionMauritania Annual Report 2016 MAURITANIA SUMMARY World Vision MAURITANIA 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 World Vision Mauritania in short . .04 A word from the National Director . .05 Strategic Objectives . .06 Education . .08 Health & Nutrition . .12 WASH . .14 Emergencies . .16 Economic Development . .22 Advocacy . .24 Faith and Development . .26 Highlights . .28 Financial Report . .30 Partners . .32 World Vision MAURITANIA 03 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 4 ALGERIA Areas of 14 interventions Programms TIRIS ZEMMOUR WESTERN SAHARA 261 Zouerat Villages 6 Nouadhibou partners PNS ADRAR DAKHLET Atar NOUADHIBOU INCHIRI Akjoujt World Vision Mauritania TAGANT HODH Nouakchott Tidjikdja ECH has a a staff of 139 including CHARGUI ElMira IN SHORT TRARZA 31 women with key positions BRAKNA in almost every department Aleg Ayoun al Atrous Rosso ASSABA Néma Kiffa GORGOL HODH Kaedi EL GHARBI GUDIMAKA Selibaby SENEGAL MALI World Vision MAURITANIA 04 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 A WORD FROM THE NATIONAL DIRECTOR Dear readers, I must hereby pay tribute to the Finally, I can’t forget our projects professional spirit of our program teams that have worked World Vision Mauritania has, by teams that work without respite constantly to raise projects’ my voice, the pleasure to present to mobilize and prepare our local performances to a level that can you its annual report that gives community partners. guarantee a better impact. We an overview on its achievements can’t end without thanking the through the 2016 fiscal year. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Rapport initial du projet Public Disclosure Authorized Amélioration de la Résilience des Communautés et de leur Sécurité Alimentaire face aux effets néfastes du Changement Climatique en Mauritanie Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable ID Projet 200609 Date de démarrage 15/08/2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Date de fin 14/08/2018 Budget total 7 803 605 USD (Fonds pour l’Adaptation) Modalité de mise en œuvre Entité Multilatérale (PAM) Public Disclosure Authorized Septembre 2014 Rapport initial du projet Table des matières Liste des figures ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Liste des tableaux ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Liste des acronymes ................................................................................................................................... 3 Résumé exécutif ........................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. Historique du projet ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Concept du montage du projet .................................................................................................. -

Centre Rachad Pour La Promotion De La Culture, La Démocratie Et La

Page 1 de 5 Elections municipales -Récapitulatif des résultats 2013 Centre Rachad pour la Promotion de la Culture, la Démocratie et la Bonne Gouvenance en Mauritanie Elections municipales des 23 Novembre et 21 Décembre 2013- Récapitulatif des résultats Wilaya Assaba Moughataa Barkeol APP + Nbre Répartition COMMUNES Partis % UPR TAWASSOUL SURSAUT PUD UDP TAWAS APP conseillers Conseillers Total SOUL UPR 11 65% 11 Barkeol 17 TAWASSOUL 6 35% 6 UPR 9 53% 9 Bou Lahrath 17 SURSAUT 8 47% 8 PUD 9 53% 9 Daghveg 17 UPR 8 47% 8 UPR 10 53% 10 El Ghabra 19 UDP 9 47% 9 APP+TAWASSOUL 9 53% 9 Gueller 17 UPR 8 47% 8 TAWASSOUL 9 53% 9 Lebheir 17 UPR 8 47% 8 APP 11 58% 11 Leoueissy 19 UPR 8 42% 8 PUD 9 53% 9 R'Didhih 17 UPR 8 47% 8 TOTAL 140 Répartition 70 15 8 18 9 9 11 140 % 50,00 10,71 5,71 12,86 6,43 6,43 7,86 100 Site Web:fr.centre-rachad.org Récépissé n° 202 du 05/08/2016 publié au J.O n° 1377 du 15 /12/2016 E-mail:[email protected] Page 2 de 5 Elections municipales -Récapitulatif des résultats 2013 Centre Rachad pour la Promotion de la Culture, la Démocratie et la Bonne Gouvenance en Mauritanie Elections municipales des 23 Novembre et 21 Décembre 2013- Récapitulatif des résultats Wilaya Assaba Moughataa Boumdeid Nbre Répartition COMMUNES Partis % UPR TAWASSOULEL WIAMSURSAUT conseillers Conseillers Total UPR 8 53% 8 Boumdeid 15 TAWASSOUL 4 27% 4 EL WIAM 3 20% 3 UPR 7 64% 7 Hsey Tine 11 TAWASSOUL 4 36% 4 UPR 9 82% 9 Laftah 11 SURSAUT 2 18% 2 TOTAL 37 Répartition 24 8 3 2 37 % 64,86 21,62 8,11 5,41 100 Site Web:fr.centre-rachad.org Récépissé n° -

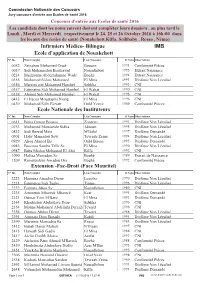

Infirmiers Médico- Bilingue IMB Ecole D'application De Nouakchott Ecole

Commission Nationale des Concours Jury concours d’entrée aux Ecoles de santé 2016 Concours d'entrée aux Ecoles de santé 2016 Les candidats dont les noms suivent doivent compléter leurs dossiers , au plus tard le Lundi , Mardi et Mercredi respectivement le 24, 25 et 26 Octobre 2016 à 16h:00 dans les locaux des écoles de santé (Nouakchott,Kiffa, Seilibaby , Rosso , Néma) Infirmiers Médico- Bilingue IMB Ecole d'application de Nouakchott N° Ins Nom Complet Lieu Naissance D Naiss Observations 0052 Zeinabou Mohamed Cissé Bouanz 1991 Conformité Pièces 0057 Sidi Mohamedou Bouleayad Nouadhibou 1995 Extrait Naissance 0214 Maimouna Abderrahmane Wade Boghé 1994 Extrait Naissance 0355 Mohamed Sidaty Mohamed El Mina 1993 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0356 Mareim sidi Mohamed Hambel Sebkha 1993 CNI 0357 Fatimetou Sidi Mohamed Hambel El Wahat 1990 CNI 0358 Ahmed Sidi Mohamed Hambel El Wahat 1996 CNI 0413 El Hacen Moustapha Niang El Mina 1996 CNI 0439 Mohamed Silly Eleyatt Ould Yengé 1989 Conformité Pièces Ecole Nationale des Instituteurs N° Ins Nom Complet Lieu Naissance D Naiss Observations 0611 Binta Oumar Bousso Zoueratt 1993 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0753 Mohamed Mousseide Sidha Akjoujt 1995 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0832 Sidi Bezeid Mein M'Balal 1997 Diplôme Demandé 0901 Haby Mamadou Sow Tevragh Zeina 1994 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0929 Aliou Ahmed Ba Ould Birom 1995 Diplôme Demandé 0983 Bassirou Samba Tally Sy El Mina 1990 Diplôme Non Légalisé 0987 Baba Medou Mohamed El Abd Kiffa 1992 CNI 1090 Hafssa Mamadou Sy Boghé 1989 Extrait de Naissance 1209 Ramatoulaye Amadou Dia -

Looters Vs. Traitors: the Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and Its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire

Looters vs. Traitors: The Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire Abstract: Since 2012, when broadcasting licenses were granted to various private television and radio stations in Mauritania, the controversy around the Battle of Um Tounsi (and Mauritania’s colonial past more generally) has grown substantially. One of the results of this unprecedented level of media freedom has been the prop- agation of views defending the Mauritanian resistance (muqawama in Arabic) to French colonization. On the one hand, verbal and written accounts have emerged which paint certain groups and actors as French colonial power sympathizers. At the same time, various online publications have responded by seriously questioning the very existence of a structured resistance to colonization. This article, drawing pre- dominantly on local sources, highlights the importance of this controversy in study- ing the western Saharan region social model and its contemporary uses. African Studies Review, Volume 63, Number 2 (June 2020), pp. 258– 280 Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba is Professor of History and Sociolinguistics at the University of Nouakchott, Mauritania (Ph.D. University of Provence (Aix- Marseille I); Fulbright Scholar resident at Northwestern University 2012–2013), and a Senior Research Consultant at the CAPSAHARA project (ERC-2016- StG-716467). E-mail: [email protected] Francisco Freire is an Anthropologist (Ph.D. Universidade Nova de Lisboa 2009) at CRIA–NOVA FCSH (Lisbon, Portugal). He is the Principal Investigator of the European Research Council funded project CAPSAHARA: Critical Approaches to Politics, Social Activism and Islamic Militancy in the Western Saharan Region (ERC-2016-StG-716467). -

Writing Trans-Saharan History: Methods, Sources and Interpretations Across the African Divide

Writing Trans-Saharan History: Methods, Sources and Interpretations Across the African Divide GHISLAINE LYDON For ages, the Sahara has been portrayed as an ‘empty-quarter’ where only nomads on their spiteful camels dare to tread. Colonial ethnographic templates reinforced perceptions about the Sahara as a ‘natural’ boundary between the North and the rest of Africa, separating ‘White’ and ‘Black’ Africa and, by extension, ‘Arabs’ and ‘Berbers’ from ‘Africans’. Con- sequently, very few scholars have ventured into the Sahara despite the overwhelming historical evidence pointing to the interactions, interdependencies and shared histories of neighbouring African countries. By transcending the artificial ‘Saharan frontier’, it is easy to see that the Sahara has always been a hybrid space of cross-cultural interactions marked by continuous flows of peoples, ideas and goods. This paper discusses a methodological approach for writing Saharan history which seeks to transcend this artificial divide and is necessarily transnational. As a scholar of nineteenth and early twentieth century trans-Saharan history, I retrace the steps of trading families across several generations and markets. This research itinerary crisscrossed Saharan regions of Western Africa from Senegal, the Gambia and Mali, to the Islamic Republic of Mauritania and the Kingdom of Morocco, with stops in archi- val repositories in France. With specific reference to the art of writing African history, I discuss how my own path into the African past was shaped by ad hoc encounters with peoples, their memories and texts. But if the facts, perspectives and narratives that form the evidence I rely upon to reconstruct trans-Saharan history were collected on an accidental trajectory, the interpretation of this data followed a deliberate methodological approach. -

Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N Akjoujt ! U479 ATLANTIC OCEAN U Uu435

! ! 20°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W Laayoune / El Aaiun .! !(Smara ! ! Cabo Bu Craa Bojador!( Western Sahara 25°0'0"N ! 25°0'0"N Guelta Zemmur Distances shown in the table and the map are indicative. They have been calculated following the shortest route on main roads. Tracks have not been considered as a main road. Ad Dakhla (! Tiris Zemmour Algeria !( Zouerate ! Bir Gandus Nouadhibou Adrar !( Dakhlet Nouadhibou Uad Guenifa (! ! Atar Chinguetti Inchiri Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N Akjoujt ! u479 ATLANTIC OCEAN u uu435 Tagant Tidjikja ! Nouakchott uu9 Hodh Ech Chargui (! Nbeika Nouakchott Trarza ! uu157 Boutilimit Magta` Lahjar uu202 ! ! uu346 uu101 Aleg ! Mal (! ! u165 Brakna u !Guerou Bourem uu6 Bogue Kiffa 'Ayoun el 'Atrous Nema Tombouctou! uu66 Rosso ! (! Assaba (! 210 (! (! uu 276 (!!( Tekane ! uu Goundam ! Richard-Toll !uu107 Lekseiba Timbedgha Gao Bababe ! Tintane ! !( ! Hodh El Gharbi ( uu116 !Mbout !( Kaedi uu188 Bassikounou Saint-Louis uu183 Bou Gadoum !( Gorgol (! Guidimaka !Hamoud !(Louga uu107 Bousteile! !( Kersani 'Adel Bagrou Tanal ! ! Niminiama (! Nioro Nara 15°0'0"N Thies Touba Gouraye Diadji ! 15°0'0"N Senegal ! Selibabi du Sahel Sandigui Burkina (! !( Douentza !( ! Sandare !( Mbake Khabou Guidimaka Salmossi Dakar .!Rufisque Faso 20°0'0"W Diourbel 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W !( !( !( Mopti Bandiagara ! Sikire Gorom-Gorom Mbour Kayes Niono! !( Linking Roads Road Network Date Created: ! 05 - DEC -2012 ! (! Reference Town National Boundar!y Map Num: LogCluster-MRT-007-A2 ! Primary Road ! Coord.System/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 -

Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N

!ho o Õ o !ho !h h !o ! o! o 20°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 0°0'0" Laayoune / El Aaiun HASSAN I LAAYOUNE !h.!(!o SMARAÕ !(Smara !o ! Cabo Bu Craa Algeria Bojador!( o Western Sahara BIR MOGHREIN 25°0'0"N ! 25°0'0"N Guelta Zemmur Ad Dakhla h (!o DAKHLA Tiris Zemmour DAJLA !(! ZOUERAT o o!( FDERIK AIRPORT Zouerate ! Bir Gandus o Nouadhibou NOUADHIBOU (!!o Adrar ! ( Dakhlet Nouadhibou Uad Guenifa !h NOUADHIBOU ! Atar (!o ! ATAR Chinguetti Inchiri Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N AKJOUJT o ! ATLANTIC OCEAN Akjoujt Tagant TIDJIKJA ! o o o Tidjikja TICHITT Nouakchott Nouakchott Hodh Ech Chargui (!o NOUAKCHOTT Nbeika !h.! Trarza ! ! NOUAKCHOTT MOUDJERIA o Moudjeria o !Boutilimit BOUTILIMIT ! Magta` Lahjar o Mal ! TAMCHAKETT Aleg! ! Brakna AIOUN EL ATROUSS !Guerou Bourem PODOR AIRPORTo NEMA Tombouctou! o ABBAYE 'Ayoun el 'Atrous TOMBOUCTOU Kiffa o! (!o o Rosso ! !( !( ! !( o Assaba o KIFFA Nema !( Tekane Bogue Bababe o ! o Goundam! ! Timbedgha Gao Richard-Toll RICHARD TOLL KAEDI o ! Tintane ! DAHARA GOUNDAM !( SAINT LOUIS o!( Lekseiba Hodh El Gharbi TIMBEDRA (!o Mbout o !( Gorgol ! NIAFUNKE o Kaedi ! Kankossa Bassikounou KOROGOUSSOU Saint-Louis o Bou Gadoum !( ! o Guidimaka !( !Hamoud BASSIKOUNOU ! Bousteile! Louga OURO SOGUI AIRPORT o ! DODJI o Maghama Ould !( Kersani ! Yenje ! o 'Adel Bagrou Tanal o !o NIORO DU SAHEL SELIBABY YELIMANE ! NARA Niminiama! o! o ! Nioro 15°0'0"N Nara ! 15°0'0"N Selibabi Diadji ! DOUTENZA LEOPOLD SEDAR SENGHOR INTL Thies Touba Senegal Gouraye! du Sahel Sandigui (! Douentza Burkina (! !( o ! (!o !( Mbake Sandare! -

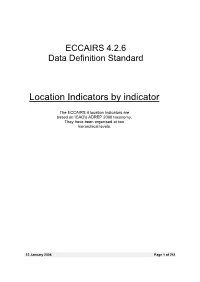

Location Indicators by Indicator

ECCAIRS 4.2.6 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by indicator The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 12 January 2006 Page 1 of 251 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by Indicator Data Definition Standard OAAD OAAD : Amdar 1001 Afghanistan OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi 1002 Afghanistan OAAS OAAS : Asmar 1003 Afghanistan OABG OABG : Baghlan 1004 Afghanistan OABR OABR : Bamar 1005 Afghanistan OABN OABN : Bamyan 1006 Afghanistan OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan 1007 Afghanistan OABD OABD : Behsood 1008 Afghanistan OABT OABT : Bost 1009 Afghanistan OACC OACC : Chakhcharan 1010 Afghanistan OACB OACB : Charburjak 1011 Afghanistan OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof 1012 Afghanistan OADZ OADZ : Darwaz 1013 Afghanistan OADD OADD : Dawlatabad 1014 Afghanistan OAOO OAOO : Deshoo 1015 Afghanistan OADV OADV : Devar 1016 Afghanistan OARM OARM : Dilaram 1017 Afghanistan OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem 1018 Afghanistan OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad 1019 Afghanistan OAFR OAFR : Farah 1020 Afghanistan OAGD OAGD : Gader 1021 Afghanistan OAGZ OAGZ : Gardez 1022 Afghanistan OAGS OAGS : Gasar 1023 Afghanistan OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad 1024 Afghanistan OAGN OAGN : Ghazni 1025 Afghanistan OAGM OAGM : Ghelmeen 1026 Afghanistan OAGL OAGL : Gulistan 1027 Afghanistan OAHJ OAHJ : Hajigak 1028 Afghanistan OAHE OAHE : Hazrat eman 1029 Afghanistan OAHR OAHR : Herat 1030 Afghanistan OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala 1031 Afghanistan OAJS OAJS : Jabul saraj 1032 Afghanistan OAJL OAJL : Jalalabad 1033 Afghanistan OAJW OAJW : Jawand 1034