A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

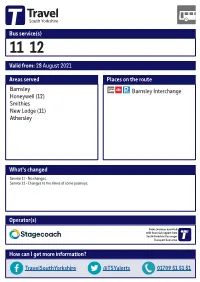

Valid From: 28 August 2021 Bus Service(S

Bus service(s) 11 12 Valid from: 28 August 2021 Areas served Places on the route Barnsley Barnsley Interchange Honeywell (12) Smithies New Lodge (11) Athersley What’s changed Service 11 - No changes. Service 12 - Changes to the times of some journeys. Operator(s) Some journeys operated with financial support from South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 11 and 12 15/05/2015 Athersley North, Ollerton Rd/Trowell Way Athersley North, 11Í Lindhurst Rd/Kirkby Av 11Ð Carlton Mapplewell New Lodge, Laithes Ln/ Roundhouse Athersley South, Derwent Rd/Peveril Cres New Lodge, Wakefield Rd/Laithes Ln Athersley South, Chatsworth Rd/Ashbourne Rd New Lodge Athersley South 12Ó 12Ò Athersley South, 11 Carlton Rd/Aldbury Cl Smithies, Wakefield Rd/Rotherham Rd Smithies, Wakefield Rd/Brunswick Cl 11 11 Smithies, Carlton Rd/ Rotherham Rd 12 12 Smithies, Smithies Ln/ Smithies Bridge Wilthorpe Honeywell Honeywell, Smithies, Wakefield Rd/Cawley Pl Monk Bretton Honeywell Grove/ Halifax St 12Ï Honeywell, Rockingham St/ 12Ð Clanricarde St 11 11Ó Barnsley, Harbrough Hill Rd/Old Mill Bridge Gawber 11Ò database right 2015 and yright p o c own r C data © y e Hoyle Mill v Sur Barnsley, Interchange e 11 12 c dnan r O ontains C = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop Stopping points for service 11 Barnsley, Interchange Eldon Street North Old Mill Lane Smithies Wakefi eld Road New Lodge Laithes -

2006-07 Annual Report & Accounts

Barnsley HospitalNHSBarnsley Trust Foundation Annual Report Annual Report & Accounts & Accounts 2006/07 2006/07 Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Gawber Road Barnsley South Yorkshire S75 2EP Annual Report&Accounts Tel. 01226 730000 www.bhnft.nhs.uk 2006/07 This document is printed on paper produced from 75% recycled fibre. Design by: vividcreative.com © 2007 V4219 V4219_BRNSLY_NHS Report07_AW 12/7/07 4:32 pm Page 3 Annual Report & Accounts 2006/07 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 1 of the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003, Schedule 1, paragraph 25 (4). V4219_BRNSLY_NHS Report07_AW 12/7/07 4:32 pm Page 4 Contents Chairman’s message 5 Chief Executive’s message 7 Operating and financial review 8 i. Introduction 8 ii. Providing high quality, low risk care 9 iii. Achieving success in a choice environment 14 iv. Improving efficiency 16 v. Creating new income opportunities 19 vi.Working in partnership 21 vii. Making a social contribution 22 viii. Financial overview 24 Governing Council 25 Board of Directors 28 Committees 32 Membership 34 Public interest disclosures 36 Remuneration report 39 Statement of Accounting Officer’s Responsibilities 40 Auditor’s opinion and certificate 41 Statement of Internal Control 42 Accounts 48 Annual Report & Accounts 2006/07 Telephone: 01226 730000 www.bhnft.nhs.uk V4219_BRNSLY_NHS Amended pages 2/7/07 4:30 pm Page 1 Chairman’s message The hospital year to the end of I know that whilst we continue The new system of funding that March 2007 was one of mixed to achieve targets set for the NHS, I have referred to as ‘pay as you go’, achievement. -

Trust Board (Performance and Monitoring) Tuesday 24 September 2019 at 9.30Am Small Conference Room, Wellbeing & Learning

Trust Board (performance and monitoring) Tuesday 24 September 2019 at 9.30am Small conference room, Wellbeing & learning centre, Fieldhead, Wakefield, WF1 3SP AGENDA Item Approx. Agenda item Presented by Time allotted Action Time (mins) 1. 9.30 Welcome, introductions and apologies Chair Verbal 2 To receive 2. 9.32 Declarations of interest Chair Paper 3 To receive 3. 9.35 Minutes and matters arising from previous Trust Board Chair Paper 5 To approve meeting held 30 July 2019 4. 9.40 Service User Story Director of Operations Verbal 10 To receive 5. 9.50 Chair and Chief Executive’s remarks Chair Verbal 15 To receive Chief Executive Paper 6. 10.05 Performance reports 10.05 6.1 Integrated performance report Month 5 2019/20 Director of Finance & Paper 60 To receive Resource and Director of Nursing & Quality 11.05 Break 11.15 6.2 Serious incident report Quarter 1 2019/20 Director of Nursing & Paper 10 To receive Quality Item Approx. Agenda item Presented by Time allotted Action Time (mins) 11.25 6.3 Brexit update Director of HR, OD & Paper 5 To receive Estates 7. 11.30 Business developments 11.30 7.1 South Yorkshire update including South Yorkshire & Director of HR, OD & Paper 10 To receive Bassetlaw Integrated Care System (SYBICS) Estates and Director of Strategy 11.40 7.2 West Yorkshire update including the West Yorkshire & Director of Strategy and Paper 10 To receive Harrogate Health & Care Partnership (WYHHCP) Director of Provider Development 11.50 7.2.1 Calderdale Health & Wellbeing Plan Director of Strategy Paper 10 To receive 8. -

Land West of Wakefield Road, Barnsley

2017/1451 Applicant: Mr Tim Love Description: Development of up to 232 dwellings with associated open space, road and drainage infrastructure (Outline with all matters reserved apart from means of access) (Amended Description). Site Address: Land West of Wakefield Road, Barnsley 7 representations from local residents. Cllr Platts has expressed concerns with capacity issues at Athersley Primary School and about the ability of Wakefield Road to accommodate further development given the existing high traffic flows. Site Location & Description The application site comprises of 7.73ha of land located west of Wakefield Road between New Lodge, Athersley South and Smithies. The site shares a boundary with the A61 Wakefield Road to the east. Over half of the eastern boundary is road frontage with the remaining part being set behind a site currently occupied by a car sales business and the staff car park for the Stagecoach bus depot that is located in close proximity further to the south east. The site is in close proximity to the junction with the A633 Rotherham Road and the associated mini roundabout which is located to the north east of the site. Existing residential properties are located opposite to the site on the other side of Wakefield Road. In addition the site is opposite to the Wakefield Road/Rotherham Road recreation ground which includes a range of play equipment and multi use games court. Located to the south/south east are commercial premises, including the Stagecoach bus depot and plant hire depot which are screened by a substantial tree belt. Located to the south west is a footpath which follows a disused railway line atop a well treed embankment. -

UNIT 22 WHARNCLIFFE BUSINESS PARK Off LAITHES LANE

Marland House 13 Huddersfield Road Barnsley S70 2LW Tel: 01226 791984 Mobile: 07957 167322 Web: www.chrisrowlands.co.uk Email: [email protected] 4,000 Sq. Ft INDUSTRIAL BUILDING TO LET (MAY SELL) UNIT 22 WHARNCLIFFE BUSINESS PARK off LAITHES LANE, CARLTON, BARNSLEY, SOUTH YORKSHIRE, S71 3HR SITUATION The property is located at Wharncliffe Business Park, Carlton, which is a prominently located site close to the well-established Carlton Industrial Estate four miles to the north of Barnsley. It is one of the largest and longest established industrial locations in the Barnsley Metropolitan Borough and is home to a variety of local, regional and national organisations. Barnsley is strategically well placed on the main road and motorway network. This has been enhanced by the opening of the Dearne Towns A1-M1 Link Road and by the Coalfields link road which is a spur connecting Grimethorpe two miles away with the A1-M1 road at Darfield. DESCRIPTION This is a mid-terrace steel framed industrial building with steel profile insulated high clad elevations with a private office featuring aluminium glazing to the yard side. Managing Director and Company Secretary: CM Rowlands FRICS Chris Rowlands & Co. is the trading name of Chris Rowlands & Company Limited, Company Registration No. 4232595 Registered in England at Marland House, 13 Huddersfield Road, Barnsley, S70 2LW Regulated by RICS The unit measures 63’9” x 62’9” thus providing a gross internal area of 4,000 sq. ft. The original offices occupy approximately 7.5% of the floor area although these have been adapted and extended to include an additional office, kitchen and a mezzanine store. -

To Let Former Sainsbury's, 88 Newstead Road Athersley

1 Rosemead Ingbirchworth Penistone Sheffield S36 7GQ Tel: 01226 791984 Fax: 01226 764242 Mobile: 07957 167322 Skype: chris.rowlandsandco Web: www.chrisrowlands.co.uk Email: [email protected] TO LET FORMER SAINSBURY’S, 88 NEWSTEAD ROAD ATHERSLEY NORTH, BARNSLEY, S71 3NA DUE TO RESTRICTIONS ON TRADING, CONVENIENCE STORE AND OFF- LICENCE USERS CANNOT BE CONSIDERED. PLEASE DO NOT ENQUIRE ABOUT THE BUILDING FOR SUCH USES! SITUATION The property is situated on the large residential estate at Athersley North, three miles to the north of Barnsley and just off the A61 Wakefield Road. DESCRIPTION This is a purpose built neighbourhood mini market and off licence, though the use has now ceased. The property is brick built with a concrete tiled roof. It has electric roller shutters to the main door and window. Managing Director and Company Secretary: CM Rowlands FRICS Chris Rowlands & Co. is the trading name of Chris Rowlands & Company Limited, Company Registration No. 4232595 Registered in England at Marland House, 13 Huddersfield Road, Barnsley, S70 2LW Regulated by RICS At one end of the building there is a yard and loading bay facility. ACCOMMODATION (Measured to Net Internal Area in accordance with RICS Code of Measuring Practice 6th Edition) Description Dimensions Sq. ft. Sales Area Open plan area with tiled floor and suspended ceiling 35’3” x 42’4” 1,492 including air con cassettes. There is an office partitioned out of one corner at the rear. At the front of the building is a small lobby which previously led to the rear of a cash machine. Loading Bay With robust floor and with two small lobbies off. -

United States Patent 19 11 Patent Number: 5,460,459 Morgan 45) Date of Patent: Oct

US005460459A United States Patent 19 11 Patent Number: 5,460,459 Morgan 45) Date of Patent: Oct. 24, 1995 (54) COMPRESSION FITTINGS FOR RODS, 4,708,038 11/1987 Hellnicket al. ........................ 403,343 TUBES AND PPES 4,733,442 3/1988 Asai ........................................ 403/342 (76) Inventor: Terence Morgan, 17 Lindhurst Road, FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS Athersley North, Barnsley, South 570000 3/1988 Australia. Yorkshire S71 3DB, England 2235615 6/1973 France. 1093151 11/1960 Germany. (21) Appl. No.: 80,412 Primary Examiner John T. Kwon 22 Filed: Jun. 21, 1993 Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Klauber & Jackson 30 Foreign Application Priority Data (57) ABSTRACT Jun. 24, 1992 (GB) United Kingdom .................. 92. 13353 A compression fitting comprises co-operating first and sec Oct. 3, 1992 GB United Kingdom .................. 92 20839 ond members, a first member being in the form of a sleeve-like member or a plug-like member and having a (51) Int. Cl. ............... F16B 2/O2 groove therein which reduces in depth from one end of the 52 U.S. Cl. ................. ... 403/350; 403/343; 285/318 groove to the other, and a second member adapted to be 58). Field of Search ..................................... 403/342, 343, located in said groove and to be movable relative thereto and 403/350; 285/.318,333,390 comprising a member in the form of an elongate tapered wedge formed into at least part of a helical coil, relative 56) References Cited rotation between said first member and said wedge member U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS enabling the compression fitting to be tightened onto a receiving member. 1,996,368 7/1934 Williams. -

Cab.5.3.2009111.4

Cab.5.3.200911 1.4 BARNSLEY METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL This matter is not a Key Decision within the Council's definition and has not been included in the relevant Forward Plan Report of Executive Director, Development Directorate CHURCH FARM ESTATE, MONK BRETTON - PROPOSED TRAFFIC CALMING - OBJECTIONS 1. Purpose of Report 1.1 The purpose of this report is to discuss the letters of objection received regarding the above proposed traffic calming, which has been recently advertised and to seek approval for installation of the speed cushions. 2. Recommendation 2.1 That the objections to the proposed speed cushions be considered and set aside and the installation of speed cushions, as described in the report, be approved. 3. Introduction 3.1 To summarise the previous report, which was approved by cabinet in November 2008 (cab.26.1 1.2008/4), Littleworth Lane one-way was implemented in June 2005 and complaints were received from residents of Church Farm Estate regarding the alleged increase in volume and speed of traffic travelling through the estate. Surveys were carried out which confirmed an increase in volume of approximately 50%, although average traffic speeds were not found to be excessive. 3.2 As the increase in traffic volume was of concern to the residents, Local Members asked for traffic calming measures to be considered in order to deter drivers from using the estate roads as a short cut. 3.3 There were no objections to the final proposals for installation of speed cushions on Long Causeway, Bishops Way and Monks Way from Local Members, local area forum and the emergency services. -

Hospital Services Review: Report for Governing Bodies

Hospital Services Review: Report for Governing Bodies Hospital Services Review South Yorkshire, Bassetlaw and North Derbyshire: Considering the case for change Governing Bodies Note: Annex C Methodology Hospital Services Review: Report for Governing Bodies Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Phase II project timeline ....................................................................................................................................... 4 3 Consultation ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Hospital services steering group.......................................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Reference Group .................................................................................................................................................. 7 3.3 Hosted Network Consultations ............................................................................................................................ 7 3.4 Workshop with existing networks ....................................................................................................................... 7 3.5 Trust consultation ............................................................................................................................................... -

ADULT SERVICES and HEALTH SCRUTINY PANEL Venue: Town Hall, Moorgate Street, Rotherham. Date: Thursday, 12 April 2007 Time: 9.30

ADULT SERVICES AND HEALTH SCRUTINY PANEL Venue: Town Hall, Moorgate Date: Thursday, 12 April 2007 Street, Rotherham. Time: 9.30 a.m. A G E N D A 1. To determine if the following matters are to be considered under the categories suggested in accordance with the Local Government Act 1972. 2. To determine any item which the Chairman is of the opinion should be considered as a matter of urgency. 3. Apologies for Absence 4. Declarations of Interest 5. Questions from members of the public and the press 6. Health Service - Annual Health Check (report attached) (Pages 1 - 31) 7. Local Area Agreement - Progress Report (copy attached) (Pages 32 - 58) 8. Patients' Hospital Discharge / Transfer of Care (report attached) (Pages 59 - 65) 9. Adult Services and Health Scrutiny Panel - Draft Work Programme and Scrutiny Reviews 2007/08 (report attached) (Pages 66 - 69) 10. Minutes of a meeting of the Adult Services and Health Scrutiny Panel held on 1st March, 2007 (copy attached) (Pages 70 - 73) 11. Minutes of a meeting of the Performance and Scrutiny Overview Committee held on (a) 16th February 2007, (b) 9th March, 2007 and on (c) 23rd March, 2007 (copies attached) (Pages 74 - 99) Date of Next Meeting:- Thursday, 31 May 2007 Membership:- Chairman – Councillor Doyle Vice-Chairman – Jack Councillors:- Billington, Burke, Burton, Clarke, Jackson, Turner and The Mayor (Councillor Wootton) Co-opted Members Mrs. I. Samuels, (PPI Forum Yorks Ambulance Serv), Taiba Yasseen, (REMA), Val Lindsay (Patient Public Involvement Forum), Sandra Bann (PPI Forum Rotherham PCT), Mrs. A. Clough (ROPES), Victoria Farnsworth (Speak Up), Jonathan Evans (Speak up), Mr. -

37SS Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

37SS bus time schedule & line map 37SS Athersley - Carlton (Outwood Academy) - View In Website Mode Athersley (Holy Trinity School) The 37SS bus line (Athersley - Carlton (Outwood Academy) - Athersley (Holy Trinity School)) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Athersley North <-> Carlton: 7:38 AM (2) Athersley South <-> Barnsley Town Centre: 3:09 PM (3) Carlton <-> New Lodge: 2:36 PM (4) Cudworth <-> Athersley South: 7:59 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 37SS bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 37SS bus arriving. Direction: Athersley North <-> Carlton 37SS bus Time Schedule 21 stops Athersley North <-> Carlton Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:38 AM Lindhurst Road/Rufford Avenue, Athersley North Tuesday 7:38 AM Lindhurst Road/Kirkby Avenue, Athersley North Lindhurst Road, Barnsley Wednesday 7:38 AM Lindhurst Road/Trowell Way, Athersley North Thursday 7:38 AM Friday 7:38 AM Trowell Way/Radcliffe Road, Athersley North Trowell Way, Barnsley Saturday Not Operational Ollerton Road/Trowell Way, Athersley North Ollerton Road/Egmanton Road, Athersley North Egmanton Road, Barnsley 37SS bus Info Direction: Athersley North <-> Carlton Newstead Road/Lindhurst Road, Athersley North Stops: 21 Newstead Road, Barnsley Trip Duration: 15 min Line Summary: Lindhurst Road/Rufford Avenue, Newstead Road/Strelley Road, Athersley North Athersley North, Lindhurst Road/Kirkby Avenue, Athersley North, Lindhurst Road/Trowell Way, Newstead Road/Shortƒeld Court, Athersley North Athersley -

ATHERSLEY RECREATION FC Saturday 30Th April 2016 Matchday 3.00Pm Kick Off at I2i Stadium PROGRAMME

Tadcaster Albion AFC ATHERSLEY RECREATION FC Saturday 30th April 2016 Matchday 3.00pm kick off at i2i Stadium PROGRAMME £1.50 John Smith’s FC The club is believed to have been In 1982/83 they became a founding Albion finished fourth in their first formed in 1892 as John Smith’s FC. member of the Northern Counties season in the NCEL Premier Division It wasn’t until 1923 that the Tadcaster East League, originally in the NCEL and won the NCEL President’s Cup, Albion AFC name was adopted. In Division Two North before league beating Farsley AFC 5-1 in the final. the early years the club played in the reorganisations led them to Division That was followed by an 8th place finish local York League. In 1948 Albion One in 1991. They rarely finish in the in 2011/12 and 6th in 2012/13. won the York League. They continued top half of the league in the 1990’s In the 2013/14 season Rob Northfield competing in the York League during and finished bottom in 2001/02 & resigned a few days before the start of the 1950’s & 60’s. 2003/04. the season and i2i Sports Ltd agreed Tadcaster Albion, in the early days, At the start of 2004/05, Jim Collis to take effective control of the club played home games on the site of became manager and at this point and company, with Matthew Gore the cricket ground on Station Road, becoming the new Chairman. fortunes on the pitch started to improve before moving to the Ings ground, near dramatically.