Sociophonetic Variation and Change in a Post-Industrial, South Yorkshire Speech Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter August 2016

The Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter August 2016 Welcome to the Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter Welcome to our summer newsletter. At last we have had some warmth and sunshine. But the summer solstice is long past. What is happening to our weather? Here we see its impact on animals: fewer hedgehogs, butterflies and bees, but loads of rabbits. Elsewhere some birds, such as plovers, are already migrating. And the early flooding has been taken over by dry gardens and dry allotments, let's hope for a dry harvest.. Some of the benefits of the improved weather are illustrated in our newsletter by the lovely local wedding pictures, and by the fundraising successes of the coffee mornings in the gardens (£600) and by Hovingham Village market. In the 7 years since it started £62,000 has been raised. And moving on to the past, this newsletter includes fascinating histories of Hovingham Church, Pickering Bridge and of our local connections with World War 1 and the Somme. Enjoy. Margaret Bell Pasture Lane - still no response from Trilandium to enforcement order I have spoken to the Planning Officer at Ryedale District Council and he tells me that they have had no response to the enforcement order re the paving of the road and pathways. Trilandium and Stirling Mortimer [the land owners] had until the 12th of July 2016 to respond. The Council have now written to them both again and they now have two weeks to respond. If at the end of that time they have not replied then the legal department will get involved. -

Tees Valley Climate Change Strategy 2010 - 2020 1 2 Tees Valley Climate Change Strategy 2010 - 2020 Foreword

Contents Pages Foreword 3 Statements of Support 4 - 5 Background 6 - 8 The Tees Valley Climate Change Partnership 9 - 10 Climate Change in the Tees Valley 11 - 15 The Tees Valley Emissions Baseline 16 - 19 Opportunities 20 - 21 Business 22 - 28 Housing 29 - 36 Transport 37 - 44 Our Local Environment 45 - 56 Communication and Behaviour Change 57 - 64 Endnotes 65 - 68 Glossary 69 - 70 Useful Information 71 - 72 Tees Valley Climate Change Partnership Contacts 73 - 75 Notes Page 76 Tees Valley Climate Change Strategy 2010 - 2020 1 2 Tees Valley Climate Change Strategy 2010 - 2020 Foreword "I am delighted to present the Tees Valley Climate Change Strategy. The Coalition Government has made it very clear that it believes climate change is one of the gravest threats we face, and that urgent action to reduce carbon emissions is needed. The Tees Valley Local Authorities and partners have long since recognised this threat and continue to implement a series of measures to address it. Tees Valley represents a unique blend of industrial, urban and rural areas and climate change represents a real threat, especially to our carbon emitting industries, however the assets, skills and experience we have also mean that we are well placed to maximise the opportunities presented by the transition to a Low Carbon economy. This transition will safeguard the industries and jobs we have, attract new inward investment and support the creation of new green jobs and technologies leading to a stronger and more diverse economy. This strategy represents the "coming together" of the five Tees Valley local authorities and their partners with a single aim and vision. -

Teaching the Art of Poetry Using Dialect in Your Poems

TEACHING THE ART OF POETRY USING DIALECT IN YOUR POEMS by Liz Berry hinny … glinder … jinnyspins … dayclean1 Choosing to write poems using dialect is like finding a locked box full of treasure. You know there’s all sorts of magical things inside, you just have to find the key that will let you in. So put down your notebook, close your laptop, and start listening to the voices around you. For this is the way in, the place where the strongest dialect poetry starts: a voice you can hear. That’s how writing in Black Country dialect started for me - by listening to the voices of the area I’d grown up in. The Black Country dialect has long been mocked as guttural and middle-earthy but to me it’s beautiful because the people I love best have spoken it. None of them are poets but to me their language is the stuff of poetry. I started listening more carefully, rooting around in the past. It was like digging up my own Staffordshire Hoard; a field full of spectacular words, sounds and phrases glinting out of the muck. I was inspired by other poets who’d written using dialect. The brilliant Faber Book of Vernacular Verse edited by Tom Paulin presents a wonderful alternative poetic tradition. It praises the 'springy, irreverent, chanting, often tender and intimate, vernacular voice … which speaks for an alternative community that is mostly powerless and invisible'. Contemporary poets like Kathleen Jamie, Daljit Nagra and Jen Hadfield continue the tradition in fresh and irresistible ways. Reading their work you’re bowled over by the fizz and charm of dialect and how poetry can be a powerful way of protecting and celebrating the spoken language of regions and communities. -

Trail Trips - Old Moor to Old Royston

Trail Trips - Old Moor to Old Royston RSPB Old Moor to Old Royston (return) – 20 miles (32Km) Suitable for walkers, cyclists and equestrians in parts - this section is also suitable for families who can shorten the route by turning back at either the start of the Dove Valley Trail (Aldham Junction 2.5 miles) or at Stairfoot (McDonalds 3.8 miles). TPT Map 2 Central: Derbyshire - Yorkshire RSPB Old Moor Visitor Centre Turn right once through the gate Be careful when crossing the road Starting out in the heart of Dearne Valley, at the nature reserve of RSPB Old Moor, leave the car park to the rear, cross over the bridge, through the gate (please be aware that RSPB Old Moor car park opening times vary depending on the time of year and the gates do get locked at night) and turn right . Follow the trail under the bridge, where you will notice some murals. As you come out the other side, go over the wooden bridge and continue straight on until you come to the road. Take care crossing, as the road can become busy. Once over the road, the trail is easy to follow. Shortly after crossing the road you will come across the start of the Timberland Trail if you wish you can head south on the Trans Pennine Trail to- wards Elsecar and Sheffield). Continue north along the Trail, passed Wombwell where you will come to the start of the Dove Valley Trail (follow this and it will take you to Worsbrough, Silkstone and to the historical market town of Penistone and if you keep going you will eventually end up in Southport on the west coast!!). -

Tees Valley Contents

RELOCATING TO THE TEES VALLEY CONTENTS 3. Introduction to the Tees Valley 4. Darlington 8. Yarm & Eaglescliffe 10. Marton & Nunthorpe 12. Guisborough 14. Saltburn 16. Wynyard & Hartlepool THE TEES VALLEY Countryside and coast on the doorstep; a vibrant community of creative and independent businesses; growing industry and innovative emerging sectors; a friendly, upbeat Northern nature and the perfect location from which to explore the neighbouring beauty of the North East and Yorkshire are just a few reasons why it’s great to call the Tees Valley home. Labelled the “most exciting, beautiful and friendly region in The Tees Valley provides easy access to the rest of the England” by Lonely Planet, the Tees Valley offers a fantastic country and international hubs such as London Heathrow and quality of life to balance with a successful career. Some of the Amsterdam Schiphol, with weekends away, short breaks and UK’s most scenic coastline and countryside are just a short summer holidays also within easy reach from our local Teesside commute out of the bustling town centres – providing the International Airport. perfect escape after a hard day at the office. Country and coastal retreats are close-by in Durham, Barnard Nestled between County Durham and North Yorkshire, the Tees Castle, Richmond, Redcar, Seaton Carew, Saltburn, Staithes and Valley is made up of Darlington, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Whitby and city stopovers in London, Edinburgh and Manchester Redcar & Cleveland and Stockton-on-Tees. are a relaxing two-and-a-half-hour train journey away. Newcastle, York, Leeds and the Lake District are also all within an hour’s The region has a thriving independent scene, with bars, pubs drive. -

Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby CCG Profile

January 2019 North Yorkshire Joint Strategic Needs Assessment 2019 Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby CCG Profile Introduction This profile provides an overview of population health needs in Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby CCG (HRW CCG). Greater detail on particular topics can be found in our Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) resource at www.datanorthyorkshire.org which is broken down by district. This document is structured into five parts: population, deprivation, disease prevalence, hospital admissions and mortality. It identifies the major themes which affect health in HRW CCG and presents the latest available data, so the dates vary between indicators. Summary Life expectancy is higher than England. For 2011-2015, female life expectancy in HRW CCG is 84.2 years (England: 83.1), and male life expectancy is more than three years lower than for females at 80.9 years (England: 79.4) [1]. There is a high proportion of older people. In 2017, 25.1% of the population was aged 65 and over (36,100), higher than national average (17.3%). Furthermore over 4,300 (3.0%) were age 85+, compared with 2.3% in England. [2] Some children grow up in relative poverty. In 2015, there were 10.8% of children aged 0-15 years living in low income families, compared with 19.9% in England [1]. There are pockets of deprivation. Within the CCG area, 3 Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) out of a total of 95 are amongst the 20% most deprived in England. One of them is amongst the 10% most deprived in England, in the Whitby West Cliff ward [3]. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

81 82 Valid From: 29 August 2021

Bus service(s) 81 82 Valid from: 29 August 2021 Areas served Places on the route Doncaster Doncaster Frenchgate Wheatley Interchange Intake Doncaster Royal Infirmary Armthorpe (West Moor Park) What’s changed Timetable changes. Daytime on Mondays to Fridays buses will run every 15 minutes. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 81 and 82 01/04/2016# Edenthorpe Arksey Wheatley Park Ind Est Armthorpe, Armthorpe, Briar Rd/Elm Rd Church St/ Mill St Bentley 81Ô, 82 Ñ Armthorpe, Doncaster Rd/Charles Cres Wheatley Hills Armthorpe, 81 Yorkshire Way/ Lincolnshire Way Armthorpe 82 Wheatley 81 Armthorpe, Church St/Winholme Wheatley, Armthorpe Rd/ Intake, Armthorpe Rd/ Doncaster Royal Infirmary Danum Sch 81Ó, 82 Ò Intake, Armthorpe Rd/Oakhill Rd 81Ò, 82Ó Doncaster, Frenchgate Interchange Wheatley, Thorne Rd/ Intake Doncaster Royal Infirmary Armthorpe, Parkway/Nutwell Ln Doncaster, Thorne Rd/ Christ Church Rd Town Moor 81 82 Bennetthorpe database right 2016 and yright p o c Cantley own r C Hyde Park Belle Vue data © y e v Sur e c dnan r O Bessacarr ontains C 6 = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop Stopping points for service 81 Doncaster, Frenchgate Interchange Cleveland Street Hall Gate Thorne Road Town Moor Wheatley Armthorpe Road Intake Armthorpe Road Armthorpe Doncaster Road Church Street Mill Street Hatfi eld Lane Mercel Avenue Durham Lane Yorkshire Way Wickett Hern Road Nutwell -

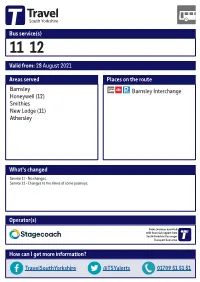

Valid From: 28 August 2021 Bus Service(S

Bus service(s) 11 12 Valid from: 28 August 2021 Areas served Places on the route Barnsley Barnsley Interchange Honeywell (12) Smithies New Lodge (11) Athersley What’s changed Service 11 - No changes. Service 12 - Changes to the times of some journeys. Operator(s) Some journeys operated with financial support from South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 11 and 12 15/05/2015 Athersley North, Ollerton Rd/Trowell Way Athersley North, 11Í Lindhurst Rd/Kirkby Av 11Ð Carlton Mapplewell New Lodge, Laithes Ln/ Roundhouse Athersley South, Derwent Rd/Peveril Cres New Lodge, Wakefield Rd/Laithes Ln Athersley South, Chatsworth Rd/Ashbourne Rd New Lodge Athersley South 12Ó 12Ò Athersley South, 11 Carlton Rd/Aldbury Cl Smithies, Wakefield Rd/Rotherham Rd Smithies, Wakefield Rd/Brunswick Cl 11 11 Smithies, Carlton Rd/ Rotherham Rd 12 12 Smithies, Smithies Ln/ Smithies Bridge Wilthorpe Honeywell Honeywell, Smithies, Wakefield Rd/Cawley Pl Monk Bretton Honeywell Grove/ Halifax St 12Ï Honeywell, Rockingham St/ 12Ð Clanricarde St 11 11Ó Barnsley, Harbrough Hill Rd/Old Mill Bridge Gawber 11Ò database right 2015 and yright p o c own r C data © y e Hoyle Mill v Sur Barnsley, Interchange e 11 12 c dnan r O ontains C = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop Stopping points for service 11 Barnsley, Interchange Eldon Street North Old Mill Lane Smithies Wakefi eld Road New Lodge Laithes -

1840 Barnsley - Staincross - Barnsley 1900 Barnsley - Staincross - New Lodge

Service 1: 1840 Barnsley - Staincross - Barnsley 1900 Barnsley - Staincross - New Lodge Service 6: 1845 Barnsley - Kendray - Barnsley Service 8: 1811 Rotherham - Upper Haugh - Rotherham Service 8a: 1841 Rotherham - Upper Haugh - Rotherham Service 9: 1830 Rotherham - Sandhill - Rotherham 1910 Rotherham - Sandhill - Rawmarsh Service 11: 1830 Barnsley - Athersley North - Barnsley Service 12: 1835 Barnsley - Athersley South - Barnsley 1905 Barnsley - Athersley South -Carlton Rd Bottom Service 21a: 1810 Barnsley - Millhouse Green 1806 Millhouse Green - Barnsley Service 22x: 1820 Rotherham - Barnsley 1835 Barnsley - Rotherham Service 27: 1843 Barnsley - Wombwell 1830 Wombwell - Barnsley Service 27a: 1823 Barnsley - Grimethorpe 1900 Grimethorpe - Barnsley Service 28: 1705 Barnsley - Pontefract Service 28c: 1835 Pontefract - Barnsley 1803 Barnsley - Hemsworth Service 43: 1910 Barnsley - Pogmoor - Barnsley Service 44: 1839 Barnsley - Kingstone - Barnsley Service 57: 1840 Barnsley - Royston,Meadstead Drive 1820 Royston,Meadstead Drive - Barnsley Service 59: 1715 Barnsley - Wakefield 1820 Wakefield - Barnsley Service 66: 1835 Barnsley - Hoyland - Elsecar - Barnsley Service 67: 1810 Barnsley - Jump - Wombwell 1830 Wombwell - Jump - Barnsley Service 67a: 1707 Barnsley - Pilley - Wombwell 1720 Wombwell - Pilley - Barnsley Service 67c: 1637 Barnsley - Tankersley - Wombwell 1650 Wombwell - Tankersley - Barnsley Service 93: 1815 Barnsley - Woolley Grange 1842 Woolley Grange - Barnsley Service 94a: 1900 Barnsley - Cawthorne 1825 Cawthorne - Barnsley Service -

2006-07 Annual Report & Accounts

Barnsley HospitalNHSBarnsley Trust Foundation Annual Report Annual Report & Accounts & Accounts 2006/07 2006/07 Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Gawber Road Barnsley South Yorkshire S75 2EP Annual Report&Accounts Tel. 01226 730000 www.bhnft.nhs.uk 2006/07 This document is printed on paper produced from 75% recycled fibre. Design by: vividcreative.com © 2007 V4219 V4219_BRNSLY_NHS Report07_AW 12/7/07 4:32 pm Page 3 Annual Report & Accounts 2006/07 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 1 of the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003, Schedule 1, paragraph 25 (4). V4219_BRNSLY_NHS Report07_AW 12/7/07 4:32 pm Page 4 Contents Chairman’s message 5 Chief Executive’s message 7 Operating and financial review 8 i. Introduction 8 ii. Providing high quality, low risk care 9 iii. Achieving success in a choice environment 14 iv. Improving efficiency 16 v. Creating new income opportunities 19 vi.Working in partnership 21 vii. Making a social contribution 22 viii. Financial overview 24 Governing Council 25 Board of Directors 28 Committees 32 Membership 34 Public interest disclosures 36 Remuneration report 39 Statement of Accounting Officer’s Responsibilities 40 Auditor’s opinion and certificate 41 Statement of Internal Control 42 Accounts 48 Annual Report & Accounts 2006/07 Telephone: 01226 730000 www.bhnft.nhs.uk V4219_BRNSLY_NHS Amended pages 2/7/07 4:30 pm Page 1 Chairman’s message The hospital year to the end of I know that whilst we continue The new system of funding that March 2007 was one of mixed to achieve targets set for the NHS, I have referred to as ‘pay as you go’, achievement. -

The Paddocks Brawby, Near Malton

THE PADDOCKS BRAWBY, NEAR MALTON Tel: 01653 697820 CHARTERED SURVEYORS • AUCTIONEE RS • VALUERS • L AND & ESTATE AGENTS • FINE ART & FURNIT URE ESTABLISHED 1860 THE PADDOCKS BRAWBY MALTON, NORTH YORKSHIRE Kirkbymoorside 7 miles, Malton 8 miles, Pickering 8 miles, Helmsley 13 miles, York 24 miles Distances Approximate A SUBSTANTIAL, DETACHED FAMILY HOUSE PROVIDING SIX BEDROOM ACCOMMODATION SET IN APPROXIMATELY 4.3 ACRES, INCLUDING LARGE GARDENS & GRASS PADDOCKS, LOCATED ON THE OUTSKIRTS OF THE VILLAGE WITH OPEN VIEWS. __________________ SPACIOUS ACCOMMODATION EXTENDING TO OVER 2,300 FT 2 WHICH BRIEFLY COMPRISES HALL – 24FT LOUNGE – DINING ROOM – DINING KITCHEN WITH AGA & PANTRY, REAR PORCH – UTILITY ROOM – CLOAKS/SHOWER ROOM SIX BEDROOMS – BATHROOM – SHOWER ROOM __________________ AMPLE PARKING – ATTACHED DOUBLE GARAGE – LARGE GARDENS. GRASS PADDOCKS & STORAGE BUILDING WITH STABLING. __________________ PEACEFUL, RURAL LOCATION WITH SUPERB OPEN VIEWS IN ALL DIRECTIONS GUIDE PRICE £535,000 FREEHOLD 3 The Paddocks is a substantial residential smallholding comprising of a spacious, six DINING ROOM bedroom family house enjoying open countryside views along with grass paddo cks 4.90m(16'1'') x 4.00m(13'1'') and large gardens amounting to 4.3 acres in total. The house is constructed of red Living flame gas fire within a stone surround. Coving . Three wall light points. brick and understood to date from the 1940s and benefits from Upvc double glazing Casement windows to the front and side. Understairs cupboard. Fitted bookshelves. and oil fired central heating. The bright and airy accommodation is arranged over Television point. three floors; in brief it comprises: hall, 24ft lounge, dining room, dining kitchen with AGA, rear porch, utility room, cloaks/shower room, a total of six bedrooms a house KITCHEN DINER bathroom on the first floor and a wet room on the second floor.